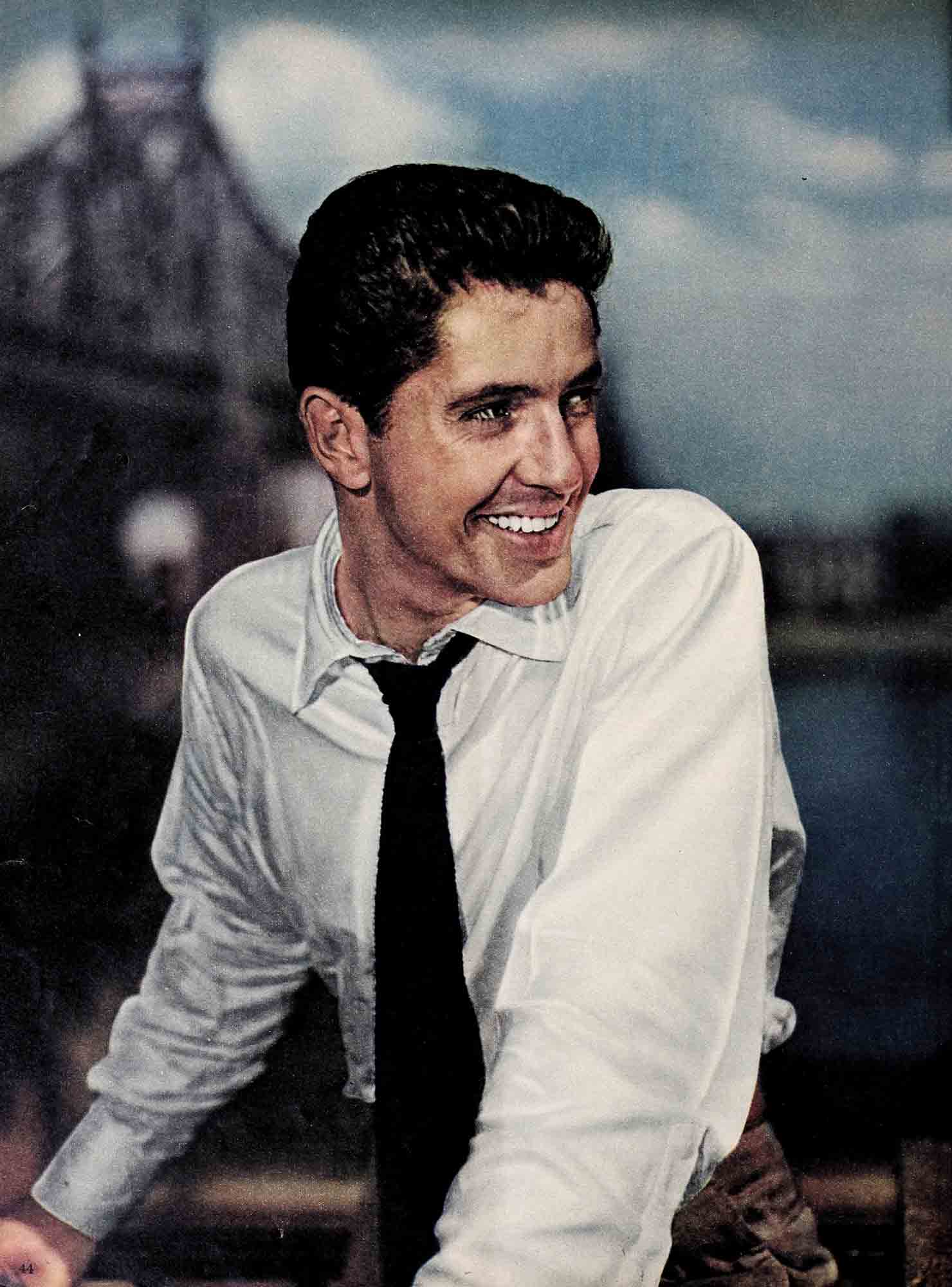

What Ails Me

People wonder what ails me. In Hollywood these days, I seem to be getting it from all sides: One rumor has it that I am getting temperamental. Another reports that I haven’t changed at all. Over the air, I hear it announced that my boss Samuel Goldwyn is finding me “difficult.” A second report states that I’m handling my career pretty well.

Confidential whispers insist I am about to get married. “They” say I am madly in love with Shelley Winters—but that Shelley is not in love with me. “They” say I am not in love with Shelley but—isn’t it sad?—she is madly in love with me.

Well, here’s the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth from me about this whole batch of talk.

AUDIO BOOK

I have changed. I’ve changed a lot. What guy—what girl, for that matter—doesn’t change between the years of seventeen and twenty-six, which is what I’ll be this July first. And particularly with two years of war service in the middle of those nine years? But I am not more temperamental. I’m less so, for a reason I’ll explain.

Nine years ago, I was a punk kid in a North Hollywood high school and I had just one dream: To get into movies.

I’d never been out of the state of California. I’d never seen anything. I was an only child, living with my father and mother.

Well, as you know, I did get into movies. My dream came true, and I’ll be forever grateful to Samuel Goldwyn, who gave me my great opportunity and who still has me under contract.

But, since that day in 1942, I’ve grown out of my teens into my mid-twenties. I’ve had a two years’ overseas stretch in the Navy. Folks like you readers of Photoplay have changed me from a “promising juvenile” in “North Star,” and made me a star in fact in “They Live by Night,” which incidentally is my own favorite among my pictures, and “Roseanna McCoy” and “Our Very Own.” (You’ll notice I’m leaving out “Edge of Doom” but I’ll come back to that for a special reason later.)

This spring, all alone, wearing nothing much but jeans, a “T” shirt and loafers, I spent four months prowling France, England, Austria, Germany and Italy. In other words, I’ve now been so many places and seen such wondrous things that I want to go to more places and see more wondrous things. I’ve sat on walls that were built 2,000 years before Christ was born and I’ve stood in a great outdoor plaza which Napoleon said was the most beautiful drawing room in the world.

A year ago, I was pretty proud about knowing a little bit about modern art. This past June, in Venice, I learned how little I knew about it, from a ten-year-old barefoot kid. When I got out of high school, and lots of times since, I’ve regarded myself as a pretty generous Joe. That got knocked in the head in London last May when two little girls contributed their sugar ration for weeks to me so that I could take a box of chocolates as a present to George Coulouris’s children.

My conception of my “ideal girl” keeps changing, and therefore my dreams of what would make a perfect marriage have changed, too.

As for my work, I love it more than I ever did, which means it utterly absorbs me, yet the ironic part of it is that I want to approach it more simply than I ever have. My feeling about the parts I now want to play is totally different from what it was two or three years ago. It is linked up somehow with the way I wish to live. Once I wanted to live like a millionaire. Even last year I wanted to live “very modern.” I don’t want either of those approaches now.

So, what about these reports of my fighting with Sam Goldwyn, not seeing so much of Shelley, and all the rest of it?

To begin with my Goldwyn squabble—because my going to Europe came out of that, and my change of feminine specifications, and even my approach to my acting came about because I did refuse to do one certain picture last spring. It wasn’t Mr. Goldwyn’s own picture, though he had the right to loan me out for it. I went on what Hollywood calls “suspension” rather than play it. That means I lost my salary—and Mr. Goldwyn lost what he’d have been paid for me. I felt that was an even enough trade. I honestly believe I will be more valuable to him, in the long run, if I don’t appear in pictures which I think will be disappointing to you people who have liked me. I believed this picture would be disappointing and so I went away. The cries that I was “ungrateful” to my boss followed me straight across the Atlantic.

That’s simply not so. I am grateful, tremendously so. He’s been like a father to me—but I want to point this out. I love my real parents devotedly. Just the same, I don’t still live with them and I don’t obediently follow their, every rule. I am an adult now and I want to act like one, even make my own mistakes, if need be.

So, maybe I made a mistake turning down that picture—but I don’t think I did. Defying my boss took the same kind of nerve it would for you to defy yours. He couldn’t fire me, that’s true, but he sure could keep me from working for anyone else—and with an actor, where youth is like money in the bank, that’s murder. Because, he could—and still can, you see, keep me from even working for him!

But I wasn’t abdicating my position, when after my trip to Europe, I came back and let him loan me to Alfred Hitchcock for “Strangers on a Train” at Warner Bros. I had a great time when I worked for Hitchcock before in “Rope.” I knew what a lot I could learn, working for that great director again. And there was more to it than that. I play a healthy, happy young tennis-playing character in “Strangers on a Train”—but that’s getting ahead of my story if I tell now why that fact delights me.

Let me tell you first about that kid in Venice and about the two little girls in London.

Those girls recognized me as Farley Granger but the kid in Venice only knew me as an American—and the way he arrived at that, was by my blue jeans. He was only ten, but he was already a working man, a sort of assistant gondolier on the Grand Canal.

He came racing toward me, yelling, “Dungarees, dungarees,” pointing first to my jeans, then to the beat-up pair cut off at the knees which he was wearing. It seems he’d got his from our Army when our G.I.’s were quartered in Italy years ago and apparently they were still his “best clothes” and he was very proud of them. He’d learned pidgin English from the G.I.’s, too, and when I told him I wanted to go to see some very special modern paintings I’d heard about in Venice he knew just where to take me—and did. Only he didn’t stop there, as I had originally meant to stop. He said, in his broken English, “But you have to see the Titians, the Raphaels, the Michelangelos” and I think he would have collapsed of disappointment, if I hadn’t agreed to go along.

Now you may think that he was just making a big noise like a guide, and watching out for a tip, and that is true. But because he did open up my eyes to art treasures I would never have thought about, I stayed several more days in Venice than I expected and I saw how much a part of their everyday life paintings and tapestry and all kinds of antique beauty are to the Italian people.

Most of them are desperately poor. To have enough to eat is a big adventure. To take a hot bath is something they plan for days before and talk about for days afterward. In other words, they get the greatest happiness out of things we take for granted. They made me mighty humble. Money, sure as blazes, got me that trip to Italy, but I saw the G.I.’s over there, who had stayed there and become civilians. They were painting, writing, whatever it was, and they were having a great time. It gave me an insight that I needed as to what you can get without money—the wonderful values you can have almost for free, if you only know enough to appreciate them. The Italians made me appreciate them.

But in England I found out that neither money nor appreciation nor “your name” will get you a thing if you haven’t got the coupons, which is where the two little girls came in.

They tagged me down the street as I came out of my hotel. They were fans just like the fans here at home, except they were much shyer, but finally they came up and asked me for an autograph and, while I was writing it, I asked them if they knew where there was a candy store. I found out they did know about George Coulouris, the actor, and I explained I was going down to the country to visit him and his wife and I wanted to take his kids some candy as a present.

“But you can’t get candy,” they said “You haven’t any coupons.”

Well, it was Sunday. The toy shops were closed, and I figured I’d have to dispense with a gift. The girls asked me where I was then going. I told them I was headed for the Tate Gallery and they asked if they might meet me there a little later. When I said yes. they went running off.

An hour later, when I left the Gallery, there they were, with a pound box of what they call “sweets.” “Would you take it?” they asked. “It isn’t much, but we pooled our coupons and we could get this amount.” All I could think of at that moment were the scores of Hollywood parties I’ve attended, where the buffet stretches through a whole garden, displaying turkeys, hams, and every other kind of food, often untouched.

Don’t misunderstand me. You only have to return from Europe to know ours is the greatest country in the world—but I had only to return to Hollywood to realize, too, that maybe we work too hard for what we want, work so hard that we don’t have time to enjoy it.

I was in Paris, for instance, on July first when some sort of what they call a “gala” was going on. Since July first is my birthday, I preferred to think it was for me—which, of course, it was not—and I stood by the Seine, that river of Paris, and watched a big display that was going on in a barge there on the river. People were all done up in flowers and a band was playing—and the barge was slowly sinking. Since nobody was in any danger, it was pretty hysterical, watching that water creep up, the people beginning to scramble off, the band ceasing to play. If we Americans have “know-how” this was plainly an occasion when these French had “don’t know-how”—and everybody’s laughter could be heard for blocks.

I was traveling alone, but I kept running into people I knew and they kept introducing me to girls, and that was great. They weren’t as pretty as Hollywood girls and not nearly as hep. But they had more dignity, they had more culture, they all could cook like dreams, and the combination, in some mysterious way, made them more feminine.

When I got back home I realized how all the young actresses I know are continually “at” their careers. I can’t blame them a bit because I know I am continually “at” my own career. Yet I wondered if the girls, especially, weren’t wrong, aren’t losing something precious to them. For the first time I knew that a guy with them didn’t feel terribly protective, or even terribly conquering. You knew those girls would be able to manage anything, conquer anything.

Which brings me finally to the different kind of roles I want and to “Edge of Doom.” “Edge of Doom” was an off-beat picture, but I always wanted to do it. I thought that fellow was an interesting character, rather gloomy admittedly, probably neurotic, but interesting.

Well, now that I’ve seen Europe’s suffering, now that I’ve seen the need to grab the tiniest bits of happiness, to live in the immediate present, I know I want to play happy people in the future, in happy situations. I want to be part of a real love story—and now, honestly, I’d rather send people away from a theater smiling or laughing than I would deeply thinking or weeping. Which is exactly why I like “Strangers on a Train”—I’m just an average fellow in that.

And I don’t think any part of this is being temperamental. I think it’s like my giving up my extremely “modern” apartment when I came back and my very modern furniture and an address on a slick, smooth modern street, for a small, quite old house up in the hills that bears upon it the visible marks of people having lived happily there for years. It isn’t “fashionable.” It will never be “amusing.” But it’s solid, and comfortable and quiet. It’s for me—right now at least.

You see, I think all that ails me is that I’ve finally grown up.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1951

AUDIO BOOK

vorbelutr ioperbir

6 Temmuz 2023Its like you read my mind! You seem to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with some pics to drive the message home a little bit, but other than that, this is wonderful blog. An excellent read. I will certainly be back.

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023I’ll right away take hold of your rss feed as I can’t to find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly allow me recognize so that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

graliontorile

11 Ağustos 2023Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!