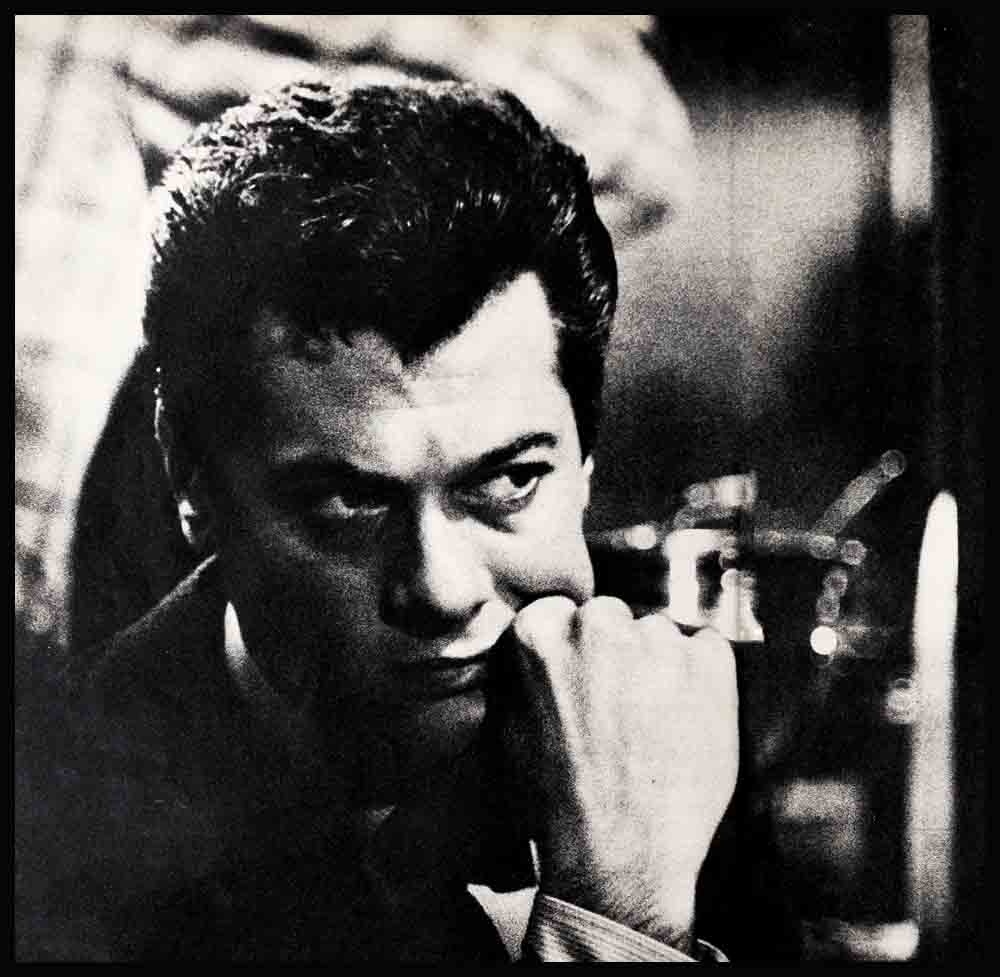

Running Scared—By Tony Curtis

It was a beautiful day, clear and sunny, the kind that makes a person feel glad to be alive. I slammed the door of my car and stood for a moment, looking up and down the street. There were some kids playing ball in a vacant lot, a policeman passing the time of day with a grocer on the corner. The sound of laughter and juke box music came from the open door of a bar. A nice day. For everybody, it seemed—except for me.

Glad to be alive? I was anything but! Walking down the street was an effort. I looked at the buildings for the number, hoping I wouldn’t find it. But there it was. I stood for a while, just looking at it, until I knew I couldn’t put off going inside any longer. My hand on the doorknob was clammy. I pushed it open, and my heart started to pound so hard I could feel it. I, Tony Curtis, was going to see a psychiatrist.

This is the story of what happened inside that office, from that day, four years ago. Six months ago, I couldn’t have told it. It struck too deep, was too painful. But now, I feel that I can talk about it, fully and freely.

Why? Because I feel it may be of help to people. Some friends of mine warned me, “You know what will happen. Some people will think you’re putting on a Pagliacci act, crying on the public shoulder. You don’t want that, Tony.” No, I don’t. But I’ll risk it, for the sake of a lot of folks I know won’t feel that way. Folks who have written me—teen-agers and adults, too—saying that they were troubled. They heard I was going to a psychiatrist, and they want to know whether I’d advise them to do the same and what my reactions were.

Well, truthfully, the first time I went I was scared stiff. But I wasn’t going to show it—not me! After all, I knew pretty much about what went on in a psychiatrist’s office.

“Where’s the couch?” I tried to make the question sound breezy. But I was surprised that there wasn’t a couch in sight. Everybody knew that was standard equipment—the place where you stretched out and bared your soul.

I tried to keep up the banter as the doctor waved to a comfortable chair, and I sat down on the edge of it. “What do I talk about?” I blurted. “Sex?”

He smiled. “If you like.”

So I told him about my first girl. When I was going to P. S. Eighty-two in New York—I was going on twelve years old—I fell in love with a cute little blonde who wouldn’t have a thing to do with me. I used to pass notes to her which she would tear up and throw away. She treated me with terrible disdain, and once when I tried to put my arm around her, she slapped me. I felt miserable.

Then I got acquainted with Ann. She had her troubles, too. There was a big sear on her face as a result of an accident she had been in. None of the guys would go out with her and somebody told me that she gave kissing lessons in the back of the school, so I asked her.

“Sure,” she said, “ten cents a kiss.”

I told her I didn’t have a dime, but she said that didn’t matter. She’d trust me. We went walking and when it was about dark she sat down with me on a bench under the Elevated steps. She told me to kiss her, so I did.

“You’re terrible,” she said, “you don’t even know how to pucker up.”

Looking back on it, I guess we were both terrible, but we were a couple of lonesome kids, and we became friends.

“Now, isn’t that exciting?” I asked the doctor.

“It must have had some meaning for you,” he replied, “or you wouldn’t have remembered.”

I leaned back in the chair. It was funny, but I didn’t feel nervous anymore. I felt relaxed and at ease as I hadn’t felt in ages.

I mention this to show that my experience with an analyst was not a long period of agony, as a lot of people say their “treatments” have been. The relationship between the doctor and me was like an easy conversation between friends, with only a few periods when I became disturbed.

One of these concerned my first real fight.

There was this kid who didn’t like me. In fact, we had a mutual dislike, which blew up one day while we were playing on a roof top. He knocked me down and kicked me in the groin. The pain was terrific. He kept on kicking at me. I tried rolling back and forth to get out of the way and then, finding a piece of broken glass lying on the ground, I hid it in my hand. When he jumped on me, I slashed at his face with the glass. Blood gushed all over. Yelling in pain, he grabbed at his face and ran down the stairs. . . . yelling all the time at the top of his lungs.

After awhile, I dragged myself down the stairs and over into an alley way until the pain subsided. My body ached so I couldn’t straighten up. Then I sneaked home, went to my room and changed clothes so my mother wouldn’t find out. If she had asked me, I would have told her the truth—at that time I wasn’t addicted to lying. I never forgot this—even years later I’d get riled up when I thought of that kid.

For a long while afterwards, this same kid kept hounding me. One day in class at school he got me so mad that I couldn’t control myself. In anger, I jumped on his back, started to pull at his hair, and twisted his ears, hard, until he yelled. The teacher sent me to the office of the principal, a Mr. Reskob. He said to me: “Bernie, we all have a cross to bear. You’ll have this the rest of your life, whether it’s related to your family or something that bothers you in business. I don’t tell you to take things lightly, but the kind of viciousness you displayed today by jumping on the boy’s back and screaming is not the answer. You must find another way to get off ‘the kick.’ ”

There was always with me this feeling of sudden violence I couldn’t control, just under the surface, even when I became an adult.

Like the morning, shortly after my discharge from the Navy, when I woke up feeling particularly disturbed.

For some strange reason I felt drawn back to my old neighborhood, so I got dressed, put on my new suit and tie and took a subway train from the Bronx to the Seventies where I used to live. As I walked along Seventy-second Street near First Avenue, I remembered a German boy, who lived in the neighborhood, who used to roust me around. I went looking for him.

I described him to a kid who pointed out where he lived, and said that he was working. I hung around the neighborhood . . . went to the corner and got myself a chocolate egg cream, walked around some more, came back and bought a doughnut. I called my mother and told her I’d be late coming home for dinner. Then I sat down on the front stoop to his place to wait.

Just at dusk a figure came down the street and I recognized him at once. He walked up to me, stopped and said, “Wait a minute—don’t tell me. Why you’re Bernie Schwartz!”

With that I came up off the stoop, and I must have hit this boy as hard as I ever hit anybody in my life. He flew about twelve feet. I looked down on him and started to cry.

As I told my analyst about it, I looked down at the floor. But I couldn’t hide the feeling of shame that I could feel was reddening my face. So I seized at a straw—an incident that was always a source of secret pride to me. I didn’t realize that it was also an outburst of violence, this time directed at things instead of people.

I had taken a kid’s dare—I had to, to show how tough I was. I jumped from the roof of a six-story building, across the alley to the roof of a four-story apartment house. Believe it or not, this was still a big thing to me, a sort of symbol of success. It was as if I was saying to myself, “Maybe I’ll fail as a career someday, but even if I do nobody else can ever say they did anything like jumping off that roof.”

My analyst pointed out that this feeling is not unusual, that people aren’t normal who don’t have a craving for achievement. But now I could see that I had used it as a protection against my terrible insecurity.

In spite of the tough act I put on, most of the time I was shy and withdrawn, and other kids used me as a “patsy” just for laughs. Once I took another dare—one that in later years cost me a big dentist’s bill. All of the kids at school used to be sent to the Guggenheim Clinic on Seventy-second Street. If you had a white card, it meant your teeth were to be cleaned. A blue card meant you needed filling. A pink card meant pull.

One day a kid said to me, “Bernie, you want to make a quarter?”

“Sure.”

“Well, all you have to do is take my card to the dentist, and when you come back. I’ll give you two-bits.”

I did. The dentist pulled out one of my rear molars. It wasn’t until years later when I came to Hollywood that I could afford to have that tooth replaced. And I never collected the quarter.

Things like this made me suspicious of everyone to the point that I began to feel there was some weakness in me. To this day I can’t see anything funny in what people call “ribbing.” I hate to be the butt of a practical joke. Like the one a couple of publicity guys played on me at the studio when I first began to work in pictures. I was so anxious to make good I fell for anything people told me.

I’d played a cowering deaf mute in one of my first pictures and these guys kept telling me afterwards that since I had done so well the studio was going to cast me as spineless characters forever. They kept building up the idea for days until I finally burst in on the casting director and shouted, “If you think I’m going to play those kind of parts you’re crazy!”

“What are you talking about?” he asked. “We don’t have anything planned for you right now.”

I was so angry I wouldn’t talk to the publicity guys for days.

I went to the analyst three times a week. His office became a pleasant, familiar place, There was a soft rug on the floor, and the colors were restful. The sun streamed through the windows in the afternoon. But it didn’t make it any easier for me to tell him all these things.

Sometimes, I’d come home shaken, as a result of having relived one of these experiences in our talks. Janet was wonderful—patient and understanding—though it must have been tough on her, too. But gradually, from the analyst I was learning something very important—the great influence of a person’s childhood experiences on his behavior as an adult. Now, I was beginning to understand why I did things I was ashamed of, in spite of myself. Why I had kept on running away from them—and myself—for so long. When I learned that it was merely a reaction set by events in my childhood, which I could not control because I didn’t understand it, it was as if a great burden had fallen from my shoulders.

But it took many a long talk in that analyst’s office before I could bring myself to talk about the thing that was bothering me most of all, because I felt terribly guilty about it—so guilty that I often woke up in the middle of the night, thinking about it. It was the death of my younger brother Julie, who was run over by a truck driven by a drunken driver when I was thirteen, and died in the hospital a day later.

A few weeks before the accident, a friend of mine named Mike took me to services at his church. When he went up to the altar rail to take communion I did exactly what he did. He was horrified. “You’ve committed a sin,” he said. “Now something terrible is going to happen.”

I felt this was one of the reasons God took my brother away from me.

When I finally succeeded in confessing this incident to the analyst, he only said, “When did you stop believing this?”

“I don’t know. I still blame myself for a lot of reasons.

“You know,” I told the analyst, “I always felt sort of responsible for Julie. I was quick, I had a sense of coordination that he lacked, but there was a sort of calm wisdom in Julie that I didn’t have. I remember that one day when he was tagging after me to school, I looked around and he was gone. I went looking and found him sitting on the steps of a church, just sort of dreaming. I bawled him out. He looked up at me in his gentle way and said, ‘Don’t hit me, Bernie. I just don’t feel like going to school today.’ So I didn’t make him go.”

What made me think of that? Was it because of the guilt I always felt that I hadn’t “looked after” Julie as well as I should have?

There was a lot more to the discussion about the death of my brother. As I talked about it with the analyst, I saw that if I hadn’t cultivated the feeling of guilt about it to the point that I could never discuss Julie’s death with my parents or anyone else without breaking down, the agony of that memory might have been erased years ago. I might have had the same result if I’d taken my problem honestly to a close friend or anyone who would listen just as the psychiatrist did.

One of the things about analysis that I’d never know was the way a simple, casual question can sometimes lead to an amazing revelation. This happened to me, when during one of these talks about my brother’s death, the analyst asked, “Did your brother ever have any other accidents?”

It came over me like a sudden shock—something I had never thought of—that a few months before the fatal accident my brother Julie had been knocked down while crossing the street, and stayed in bed for a few days with a bump on his head. A feeling of relief surged through me. I couldn’t explain why.

I think the analyst put his finger on it when he said, “You know, having a conscience about right and wrong is one thing; blaming yourself, having a feeling of guilt about something that was unavoidable is another.”

In the beginning of my analysis I was half fearful and half full of anxious anticipation, expecting that I’d find the secret of everything in one blinding flash. I was afraid that somewhere in the tangled jungle of my mind we would come up with the discovery that all my life I had resented my mother or my father. I soon got over that as I slowly realized that but for the tough environment I grew up in I was a pretty average kid, with a normal love for his parents. I didn’t get that blinding flash from this revelation about my feelings about my brother’s death, either. It wasn’t that simple.

In psychoanalysis, you don’t just sit down and unroll everything that happened to you, backwards. It’s not a case of counting them off until you come to the one that’s bothering you.

A lot of the time, during these sessions, things I remembered came in short bursts. For example, in one hour I thought about a teacher I had called Mrs. Delaney, and how sorry I felt for her when her mother and sister died on the same day. And how close I felt to her because of the sympathy she gave me when my brother died a few weeks later. How I was able to share my grief with her, but couldn’t talk about it to my own parents . . . About the day two kids jumped me and gave me a broken nose. (My mother came home from the store just as they were finishing the job, and she chased them with a new broom—gave them a terrible whacking) . . . How close my father and I were. How he built me little boats out of wood for presents because we were too poor to exchange gifts . . . The petty thievery that might have sent me to jail if it had continued.

The big moment I had half expected when a white spotlight would point out the one thing that had caused all the worries and feelings of guilt I experienced never came either. Instead, I began to realize that I was going through a gradual re-education ,with respect to my own life experiences.

For example, for a long time I assumed a sort of wise-guy attitude to cover up my lack of self-confidence. I remember how, when I had been signed to a contract at Universal, I flew out to the coast and sat next to a fellow with whom I struck up a conversation. He asked me what I did and I told him I was going to Hollywood to be an actor with Universal.

“Very interesting,” he said, “but how does it happen that you chose that company?”

“Oh,” I said, “they were all after me (a big lie), but this is the studio where a young actor gets a break. Now you take a place like Warner Brothers. Nothing. Why, they even let Clark Gable go over to Metro.”

My companion laughed. Just before we landed he introduced himself—Jack Warner!

Nobody would have believed that this was a session of psychoanalysis, if they could have seen me and my analyst laughing over that one! Everybody has an idea that it’s all grim torture, and it’s not. To put it as simply as I can, it’s just a matter of getting to understand yourself. Sometimes the process is painful, of course, but much of the time it isn’t.

All in all, ’’m glad that I did go through psychoanalysis, because the experience has helped me to understand the emotional and intellectual changes I have gone through in my life up until now, and freed me from the fear and guilt that had made me miserable. But as I said in the beginning, consulting an analyst is a step to be taken only after consultation with the family doctor, who may point out many other ways in which to achieve a better understanding of oneself and to apply common sense to one’s problems.

If my failure to point to one important revelation that analysis produced to make me a better human being seems like an anti-climax, let me say this: the secrets of a happy life were written down for everyone long ago. You can read them in the Bible. You can find them in the everyday life of ordinary people—in the unselfishness of your friends, the love of your family. There lies your security, your insurance against fear, the answer to your emotional problems. But sometimes, as in my case, it takes a long road to arrive at what you should have known in the beginning—that all people are essentially good, and you’re not so bad yourself.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1957