Hollywood’s Young Unmarrieds

The young unmarried set in Hollywood—what are they like—those girls and boys?

Thousands of letters asking this question came to the editors of Photoplay following the intimate report on Hollywood’s young married couples that was published in the February issue.

The intervening months have been spent in research and photography and we now have all the answers. Hollywood’s single boys and girls are as varied as their personalities. On three things only are they in unanimous accord. They all want to get married. They all want to have families. They all think working in the movies is a happy-making job.

How Do They Live?

Those who live at home either pay the rent or help in some other way. Joan Evans is the one exception; but she also is the youngest of the group.

The girls are inclined to buy their homes, feeling that if and when they marry, their homes can go to their families.

Rent for those who do not live at home ranges from $65 to $175 a month, the average being $105. Very few have maids.

The girls who live at home average dinner with their families about four times a week—the boys less often.

The girls who live at home are pretty well agreed that mothers are more understanding of problems than fathers.

Peggy Dow lives at the Studio Club, that amazing place where girls getting started in any branch of the movies can live and have two meals a day for twenty dollars a week. Peggy has a room of her own separated by a foyer from the room of her suite-mate, a girl who works in publicity at Warners. There are several reception rooms in which boy friends can be entertained. However, when you have an outside date, Studio Club rules require hat you be in by midnight. Another club problem is the telephone. Usually there’s a line waiting to use it. Peggy uses it once a week to call her family—needless to say this is not all she uses it for!

Ann Blyth, who owns a lovely three-bedroom house in the Toluca Lake district, lives with her Aunt Sis and Uncle Pat. Aunt Sis is her late mother’s sister. Ann takes complete care of her bedroom. But she refuses to consider this a chore. “I love doing it,” she says, “my room is so beautiful.”

Betty Lynn also owns her home. With her are her mother, aunt and grandfather. Betty hates housework, only helps when “my mother gets after me.” She admits that most of their family quarrels come about because she doesn’t take enough interest in domestic matters. Her family—except her grandfather who, she says, is an angel—“scream” at her. too, for the absent-minded way she drives her car.

At the Lynns, there’s no set time for meals. Betty’s usually dashing out somewhere when her mother calls, “You get in here and get something to eat.” She’s apt to grab a bite on the go—which is all right with her mother.

Bob Stack lives in a big U-shaped house, in Bel-Air, complete with swimming-pool, tennis court and solarium. One wing of the house is Bob’s. The other wing belongs to his brother, Jim. Their mother, Betzi Langford Stack, lives in the center section. Betzi is active in charities. Jim is a businessman. Bob is an actor. All go their separate ways and decide in advance who will use the swimming pool and when. Since all three Stacks are violent individualists the layout of their house suits them perfectly. “When an argument starts, we just go to our own quarters,” says Bob.

Phyllis Kirk rents a charming little guest house on a big estate.

Nancy Davis has a small apartment.

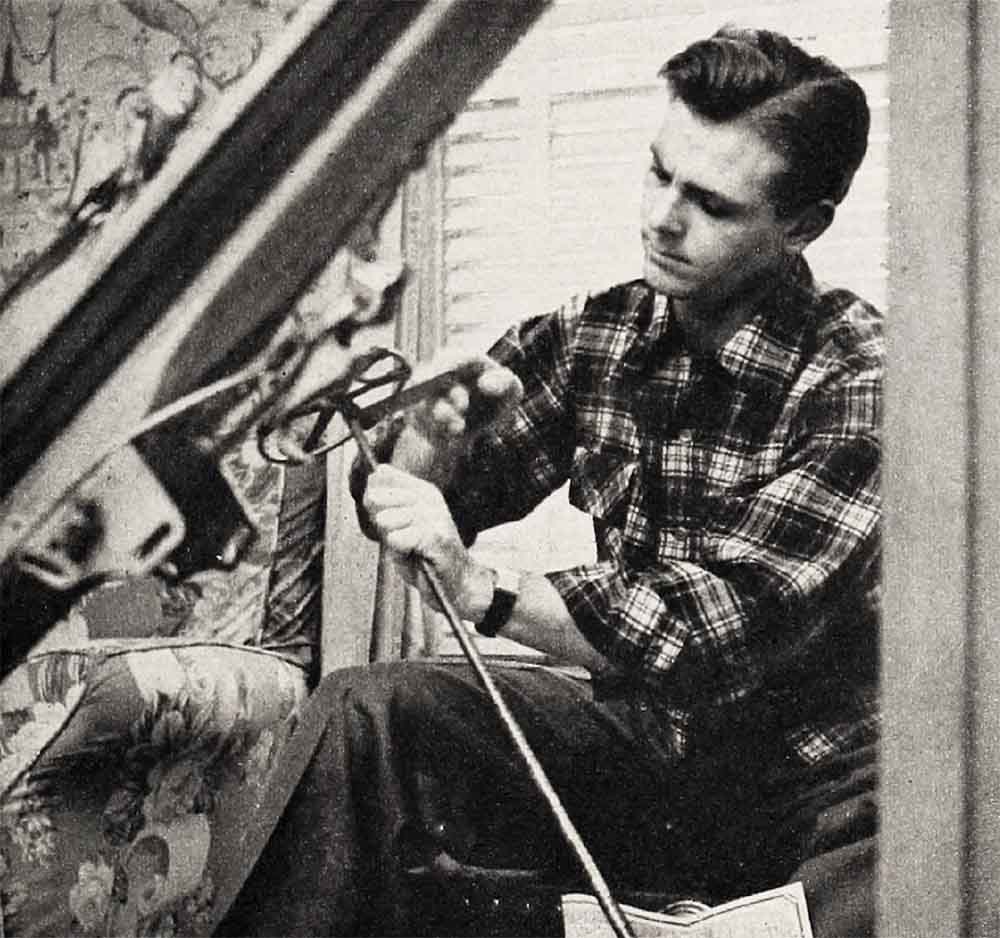

Carleton Carpenter has lived alone so long he wouldn’t have it any other way. He writes his family, who live in Vermont, about every two weeks. “When something sensational happens,” he telephones.

Wherever Carleton lives he rents a piano. Composing music is his hobby. It’s a hobby that pays off. His song “Ev’ry Other Day” is a number in his new movie “Whistle at Eaton Falls” and has been incorporated into the score.

Debra Paget, who lives with her family in a two-bedroom house, shares her bedroom with her fifteen-year-old sister. Debra does the dishes and helps clean house. And seven nights a week—unlike the other Hollywood girls and boys—Debra eats dinner at home.

Debra, at seventeen, has never had a date with a boy. “I have no desire to date,” she says. “I’m afraid if I started dating one boy after another I might get confused. I wouldn’t know the right one when he came along. Besides, I’m just interested in my career.”

Debra, her mother, father, fifteen-year-old sister and year-and-a-half-old sister live together. But her married sister and her husband and her married brother and his wife spend most of their time at the house. “We all go to the movies together. We all have fun,” Debra says. Required to make an appearance at a premiere or some other public function, Debra takes her mother along.

Was this restricted pattern the family’s idea? Debra says no. Her mother, Margaret Gibson, was in show business—a singer and comedienne. She doesn’t work now because Debra wants her with her at the studio.

Scott Brady lives in an apartment with his mother and father and two brothers—one of whom is Lawrence Tierney. “The boys are a handful,” says Mrs. Tierney, “always dashing around, eating at off hours.”

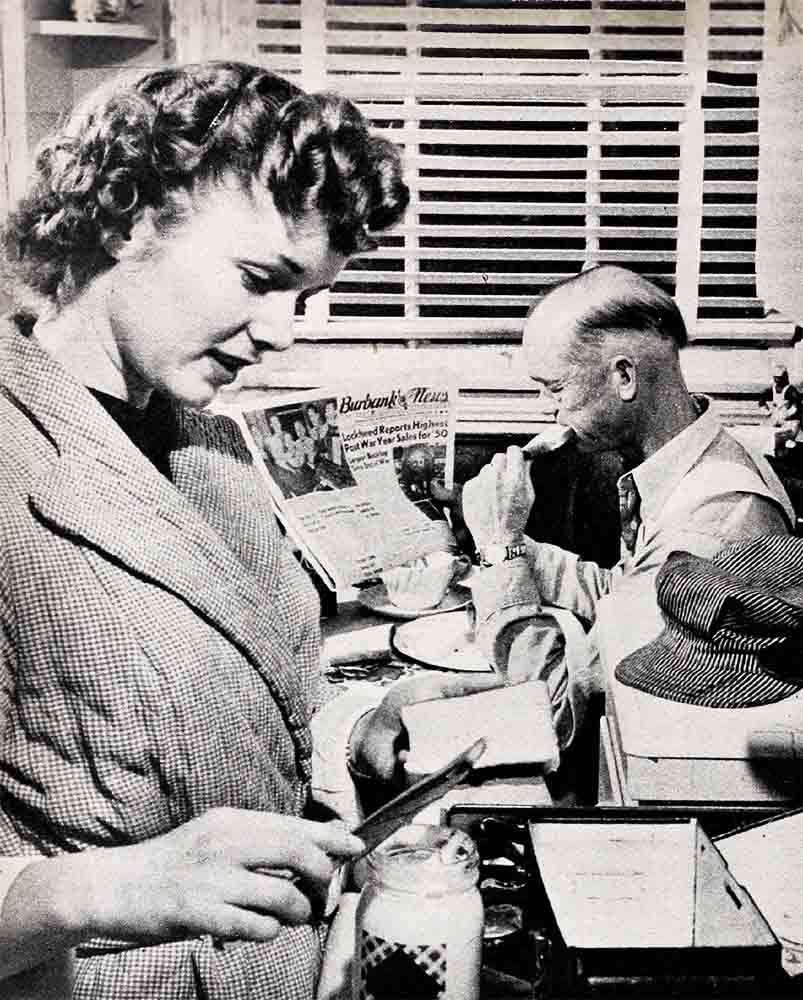

Debbie Reynolds lives in a bungalow over at Burbank, not far from the Warner Studios. It’s her father’s house and in the family are her father, mother, brother and grandfather. Debbie’s father is a railroad man and it’s Debbie’s job to fix his lunchbox. She also has to keep her room straight and do dishes. And, although Debbie is afraid nobody will believe it, she has to mow the lawn. “It’s in real bad condition now,” she admits, “I’ve been so busy away on a personal appearance tour and everything. . .”

Dale Robertson hates living alone but his family—he calls his mother twice a week—live in Oklahoma. And he does not choose to share his apartment. “It gets too embarrassing,” he says, “when you can’t stand the guy you’re living with any more. How do you tell him to leave?”

Rock Hudson agrees.

Joan Evans has an apartment under her parents’ roof. The house, built on a hillside, has three levels. The lower level consists of living room, bedroom, bath and small kitchen. This is Joan’s. Joan is constantly in difficulty over the state of her apartment, always promising she will “try to do better” about keeping it picked up.

Joan and her family—her mother, father and grandmother—do not quarrel. But they have really violent arguments, usually about who is a better writer or director or actor. Joan says, “If I’m wrong, I say I’m sorry If I’m right and have not been convinced I just won’t give in.”

Craig Hill prefers to live alone, too. However, since his family are close by at Laguna Beach, where his father has an automobile agency, he spends weekends at home-unless there’s snow in the mountains. Then he goes skiing.

Tony Curtis lives with his mother, father and kid brother in a small apartment. But he’s planning to buy his family a home so they’ll be all set. Tony doesn’t help much around the house, because he works hard and bribes Bobby to do certain chores for him.

Tony’s father, a tailor, hates the way Tony dresses. He plans Tony’s outfit before Tony leaves the house. To save argument, Tony puts the tie he wants to wear in his pocket and changes in the car. Tony and his mother have a problem—his shirts. “Whenever I don’t need a shirt, they’re all ironed,” Tony says. “But when I call and tell Mom I’m going out and need one she forgets.” How is this argument settled? “Mom irons the shirt while I’m shaving.” His arguments with his brother are likely to be over his record collection. “If he breaks one,” Tony says, “he carefully puts it back in the album, then is surprised to see it broken”

How They Date

For the most part the Hollywood kids determine their own curfew.

The girls’ families always meet their boy friends.

Movies are a favorite date with a stop afterwards for coffee at a drive-in or ice cream at Wil Wrights.

Dancing is a special date.

The average girl began dating at fourteen.

The average boy began at ten!

Mitzi Gaynor was thirteen when she had her first date. Mitzi was a ballet dancer and when she played San Francisco she met a beautiful theater usher named Fred. They went out after the show and had black and white sodas and grilled cheese sandwiches.

Now Mitzi’s engaged to a “big beautiful man named Richard.” They have a date every Thursday night at least. “That’s our anniversary date,” Mitzi tells you. “We met on a Thursday.”

Regarding her dates Nancy Davis says, “I put rules on myself and get in at the same time I would if I lived at home.” Since Nancy is a girl who requires a lot of sleep she never goes out at night when she’s working on a picture. Small dinner parties at home are her joy. She limits these to once or twice a week, on the days she has her visiting maid. Nancy says she’s never gone Dutch on a Hollywood date. But she did often in New York.

Joan Evans goes Dutch a lot because, as she says, “I know so many starving young actors.” Joan dates boys in the industry almost exclusively. “They seem to understand my problems. Besides, I’m so new to this business that actor-talk simply thrills me. I want to talk about pictures all the time.”

Joan’s first date was an Exeter prom. “I was the youngest girl there,” she says. “But my mother worked on the theory that unless I had been ready to handle myself well, unless I was adult enough to accept the responsibility of a date like that, I wouldn’t have been asked.”

Joan loves to entertain in her apartment in her parents’ house, to have kids over and listen to records. Her biggest party was a house-warming. Thirty-five dropped in from nine o’clock on. At midnight she served chili that had been made early that morning and was re-heated on the hot plate in her small kitchen.

Joan’s idea of a special date is the ballet, the theater, or a concert.

Carleton Carpenter likes to get Sunday breakfast for his friends. He also has people in for dinners which he cooks. Macaroni and cheese is his specialty. Occasionally, Carleton says, he will go Dutch.

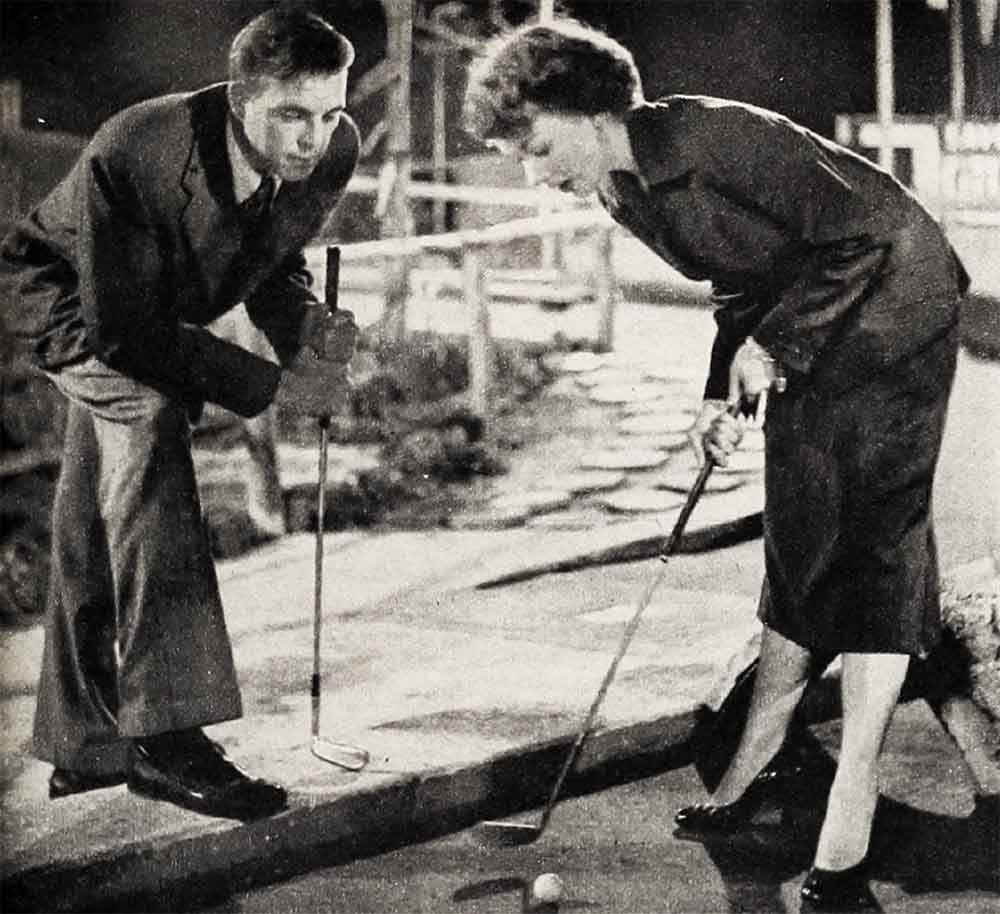

Debbie Reynolds likes to go Dutch. “And most of the boys agree,” she says, “particularly college boys who have to buy books and who aren’t earning any money.” Debbie still goes with boys she knew in high school, doesn’t mix too much with the Hollywood crowd.

Asked if there are restrictions on her dating she says with casual pride, “My family trusts me.”

Phyllis Kirk doesn’t go out with actors very much. She likes writers, she says, “and musicians, mostly one musician.” That would be Andre Previn, the brilliant young pianist who headed the M-G-M music department until he went into service. Now Phyllis, who is by way of being an intellectual, spends hours writing him.

Phyllis likes to cook buffet suppers for her friends. About special dates. she says, “I never think of a date being average or special according to what is done. It’s the guy who makes the difference.”

Dale Robertson was five years old when he started going out with a little girl who lived around the corner back in Oklahoma. “And we went together,” he says, “right straight through school.” Dale likes to have friends over after dinner for talk and TV. Out-of-doors his favorite date is to go horseback riding.

Betty Lynn goes Dutch when she’s with a bunch of professional people on tour or something like that. But she doesn’t believe in it for a real date.

Betty’s very social, loves to go out. But when she stays in she likes to have girls over for “heavy talking.”

Tony Curtis, who says he was “pushing six” when he started to date, likes to ask the kids to his place to listen to his record collection. He’ll go Dutch if he’s on layoff. “If a girl’s in accord,” he explains, “and says, ‘You’re with me tonight,’ I’m not in the least embarrassed.”

Rock Hudson will go Dutch “if a girl asks me and I’m short of cash.” He’s dated non-professional girls mostly because “a girl’s a girl and a guy’s a guy whether they’re in pictures or not.” His favorite girl now, however, is Vera-Ellen.

Rock doesn’t entertain at his apartment. “I wouldn’t,” he says, “inflict my cooking on my friends.”

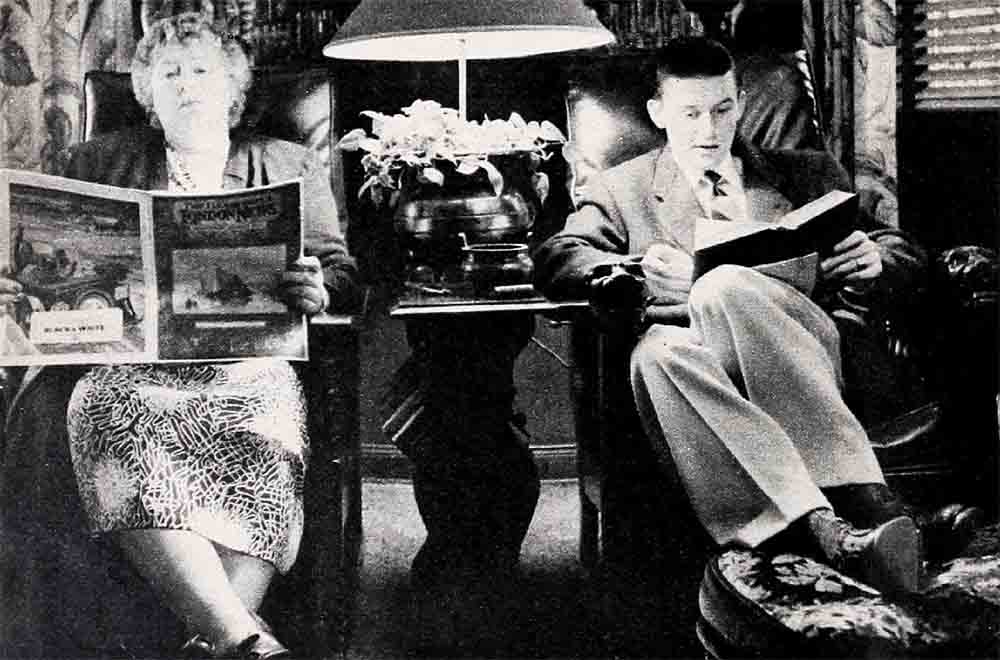

Roddy McDowall didn’t start dating until he was seventeen. Now he almost never dates non-professional girls. “I’m in love with acting,” he explains, “and actor-talk. When I take a nonprofessional girl to a Hollywood party and everyone starts talking shop I’m afraid she’ll think she’s rather out of it. I try to bring her into the conversation and say something quite foolish.”

Occasionally Roddy, who likes to entertain beside his swimming pool with barbecues, will go Dutch. “But,” he says, “I have to know the girl awfully well.”

Scott Brady was vehement about going Dutch. “No, sir, not on your life!” It’s a very special date for Scott when he takes a girl to the fights. For an average date he likes an amusement park. When he was going with Ann Blyth, he said, “She always wanted to go to the ballet.”

Peggy Dow often has friends to dinner at the Studio Club. Occasionally she goes to a night club but she doesn’t like them. “They give me a headache.” Although “crazy about actors,” Peg has a lot of nonprofessional friends whom she met when she went to Northwestern University.

Bob Stack says, “Going Dutch is silly. If you’re going to take a girl out, then do so.” Bob likes to give tennis parties at his place, followed by a buffet. He says a date is special “only if the girl is special.”

Craig Hill will go Dutch. “When it’s necessary. If the girl can afford it, then she gets to go to a lot of places she might not go to otherwise. The money can change hands before or after the date. Or one night I’ll take care of everything and the next time she will.”

How They Feel About Wolves . . . Love . . . Marriage

Not one girl would admit ever proposing to a boy. But more than half of the boys insist they’ve had proposals.

One girl had thirty-five proposals. She knows. She keeps a diary. The average was three or four.

The affair before marriage is definitely not approved.

Nancy Davis doesn’t worry about wolves. “You have to open the door to most wolves, anyhow,” she says. She admits she doesn’t tell a boy when she’s in love with him. “But,” she says, “he just knows if I am.” Nancy has learned how to say “no” to a proposal and stay friends.

Phyllis Kirk will marry, “When I feel that I am capable of taking on the responsibility—the great responsibility of marriage.” Regarding wolves she says, “A good percentage of so-called wolves are wolves because they’re encouraged to be.” On affairs before marriage, she believes it’s up to the people involved and the circumstances.

Mitzi Gaynor says she wouldn’t come right out and propose but “there’s such a thing as maneuvering.”

Mitzi let her sweetheart know when she was in love with him. “I did,” she says, “I said, ‘Darling, I’m in love with you.’ ” Mitzi, nineteen now, plans to marry when she’s twenty-one. She has never, she insists, had an experience with a Hollywood wolf.

Craig Hill, proposed to by a girl, handled the situation honestly. “It’s best,” he says. “I just told her—as nicely as I could—I wasn’t in love with her.”

Craig, who doesn’t think it hurts to let a girl know you’re mad about her, wants to marry as soon as he is financially able.

The “easy” girl. doesn’t appeal to him. “To each his own,” he says. “I don’t condemn any girl for the life she wants to lead. But I wouldn’t be seen out with an obviously willing girl.”

Betty Lynn has no luck being friendly with a boy whom she’s turned down. “We’re not chummy afterwards. I’m embarrassed. I tell a boy ‘No—at least not now.’ That’s wrong. I go into the career business, which is silly. I just say ‘no’ all wrong so we’re not friends any more.”

As for wolves she analyzes the situation simply enough, “Wolves are very conceited. Their egos are so great that they dare not risk a ‘no.’ Therefore it’s up to the girl to put up a barrier. Generally wolves can tell who will be receptive and who won’t. The smart wolves won’t try unless they think they have a chance. But, let’s face it—there are some who are not so smart.” Betty doesn’t make brash statements to any boy. But she thinks it’s always obvious how she feels. She’ll marry, she says, “when I meet the right guy.”

Joan Evans has not yet been in love—really. But she’ll let the boy know when she is. To the four proposals of marriage she has had she has replied, ‘I’m only sixteen. I have to wait.”

Joan suspects her youth has protected her from the wolves. She’s never been out with one. “I’ve met a couple,” she says, “and a couple have telephoned me. But I just haven’t made a date and they’ve gotten the idea.”

Debbie Reynolds has never really been in love either. But she too will make it known when she is. Debbie, proposed to, always says, “I’m too young for marriage.” For the wolves she has a cute question: “Would you treat your sister this way?”

Debbie used to want twenty kids. But she’s cut the number down to six.

Roddy McDowall was horrified to hear that girls propose to boys. “You mean they ask you to marry them, just like that. Say it right out? Oh, no! I’d get-out and run or tell her to get out and run.”

Roddy says he’s never been in love.

Of the affair before marriage he shrugs, “I let everybody lead his own life as long as he doesn’t bother me with it.”

Piper Laurie is another girl who hasn’t been in love. But she, too, will let the boy know when she is. She hopes to be married in two or three years. Of wolves she says, “I let wolves know how I feel about things. If they don’t like it, I don’t go out with them again.”

Ann Blyth has no doubt she will know when it is the right time to marry. “It happens when it’s supposed to,” is her theory. “Your guardian angel tells you.”

Ann’s experience with wolves has been nil. “I never go out with a boy I don’t know very well,” she says.

Carleton Carpenter proposed to a girl back home but fortunately they were both too young for marriage. The easy girl has no appeal for Carleton, who feels, “If she’s too obvious you don’t have the fun of the chase.”

Tony Curtis, speaking of the easy girl, “When I see that kind of girl I feel sorry for her. I think, ‘Gee, that’s a shame.’ ”

Tony has had a proposal of marriage—but he wasn’t prepared for any such thing and the girl wasn’t either. Tony also has proposed. However, he’s determined not to marry until he gets a house for his folks.

Debra Paget will not marry for at least five or six years. “My career is all that means anything to me now,” she says.

Scott Brady has yet to fail in love. But this doesn’t concern him. He’ll marry “when I meet someone I want to marry.”

Dale Robertson definitely believes in telling a girl you love her. He proposed once—to a girl back home. But they were too young for anything to come of it. He’ll marry, he says, “when I find someone who can put up with me and with whom I can put up.”

Bob Stack says he has never made a marriage proposal. Regarding obvious girls he says, “If you don’t have respect for the girl you take out it’s no good. You want to say to her, ‘Hey, wait a minute. What are you trying to prove?’ ”

Rock Hudson has proposed—to Vera-Ellen. He hopes she will accept him. He wants to marry “when my next option is lifted—sooner if possible.”

He doesn’t believe in the affair before marriage. But he doesn’t damn those who disagree. “It’s their business,” he says.

Sally Forrest says she is not able to establish a friendship with any boy whose proposal she has refused. “When you act as if you don’t want ’em, you get ’em,” she says. “For me it doesn’t work out too well afterwards.” Sally doesn’t have much trouble with wolves. “I just make fun of the fellow who tries to be one and don’t waste my time,” she says.

Peggy Dow thinks the best way to cope with a wolf is to make a joke of his tactics. Confronted with a proposal she’s “honest—but not brutally honest.”

How Do They Feel About Their Work—Their Generation?

Do they like these years they live in? Do they think their generation is better or worse than the generation that went before them? What is their attitude and their families’ attitude about their work?

Do they think they’ve missed anything by being in pictures?

Tony Curtis takes a dim view of his lifetime. “Everything is made too easy,” he says. “Kids’ attitude is too easy. Kids don’t work so hard. When my father was a boy he had to work far everything he got. We don’t appreciate our advantages as much as we should.”

Speaking of his career he says, “My dad is completely unimpressed. My mom is more demonstrative. And my little brother doesn’t care whether I’m in pictures or not so long as I give him a fifty-cent piece once in a while.” Speaking personally, Tony the realist says, “Where can a guy like me, at twenty-five, get a brand-new car, nice clothes, money and someone to recognize him on the Street?”

Carleton Carpenter feels he was born twenty years too late. He says, “I would have been more at home in the ’Twenties, dancing the Charleston, etc., than I am in my own generation.”

Joan Evans thinks this generation is better than the last. “We’re happier,” she says, “because we’re more honest.” Her family is happy about her career because she is happy about it. “They just wish my so-called career had not begun so soon,” Joan explains. “I was only fourteen when I signed my contract. But they were afraid to say ‘no’ for fear later they would have big regrets if things didn’t work out for me.”

Debra Paget says, “I feel there’s nothing better than having the job you want and trying to do it well.”

Debbie Reynolds says, “My parents are very average people, I’m glad to say. They think it’s nice, my being in pictures. And when I get a good write-up they say, ‘That’s swell.’ But when my brother, who loves to play baseball, tells about the home run he hit they think that’s just as swell. And—you know what?—so do I.”

Craig Hill thinks this generation is better “because we’re more mature.” And he’s glad he’s in pictures because when he works he works hard but between pictures he can ski and sail and swim.

Nancy Davis appreciates the interesting people she meets through her work.

Roddy McDowall values the people he meets and the travel he enjoys.

So does Peggy Dow. Peggy sums up her generation by saying, “I think we’ve done remarkably well.”

Piper Laurie’s family says, “If this is what she wants to do, it’s fine with us.” Piper says, “Doing a scene well—that’s the greatest thrill in the world.”

For Ann Blyth, acting is “fulfilling the dream.” And she says, “God has been so good to me that I wouldn’t have lived at any other time.”

“There’s more realism in this generation,” says Rock Hudson.

Dale Robertson says of his generation, “We’re better off because there is more opportunity for learning.”

Phyllis Kirk believes that fundamental human nature does not change, so this generation is no better, no worse than the last.

Bob Stack’s motto is “Live for today, but hope for the future.” Bob feels his postwar generation knows great confusion and frustration.

Mitzi Gaynor thinks “This generation is allowed too much freedom. There are almost no restrictions on us. So I think it is worse.”

“This generation is worse because conditions are worse,” says Betty Lynn.

These are Hollywood’s young people—a serious group living in a serious time. They’re well adjusted, generally. They face their problems honestly. But the important thing about them—and it shines through everything they say and do—is that they’re doing the work they love and they’re happy.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1951

No Comments