The Suicide That Broke Jackie’s Heart

Jackie Kennedy heard her husband’s stirring words with ears that moments before had received shattering news. She saw the beauty of the White House flower garden, newly planted and fragrant with hyacinth, through eyes that were rimmed red from weeping.

“He wept over sorrows of others. . . .” Jack’s words—spoken in praise of Sir Winston Churchill, who was being awarded honorary U.S. citizenship in an inspiring outdoor ceremony—were all too fitting for Jackie’s own case. For Jackie, too, had been weeping over the sorrows of another—another who, in many ways had lived a life like hers. And that other woman’s sorrow—there was no escaping this—had been caused in a small part by Jackie’s own brother-in-law, Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

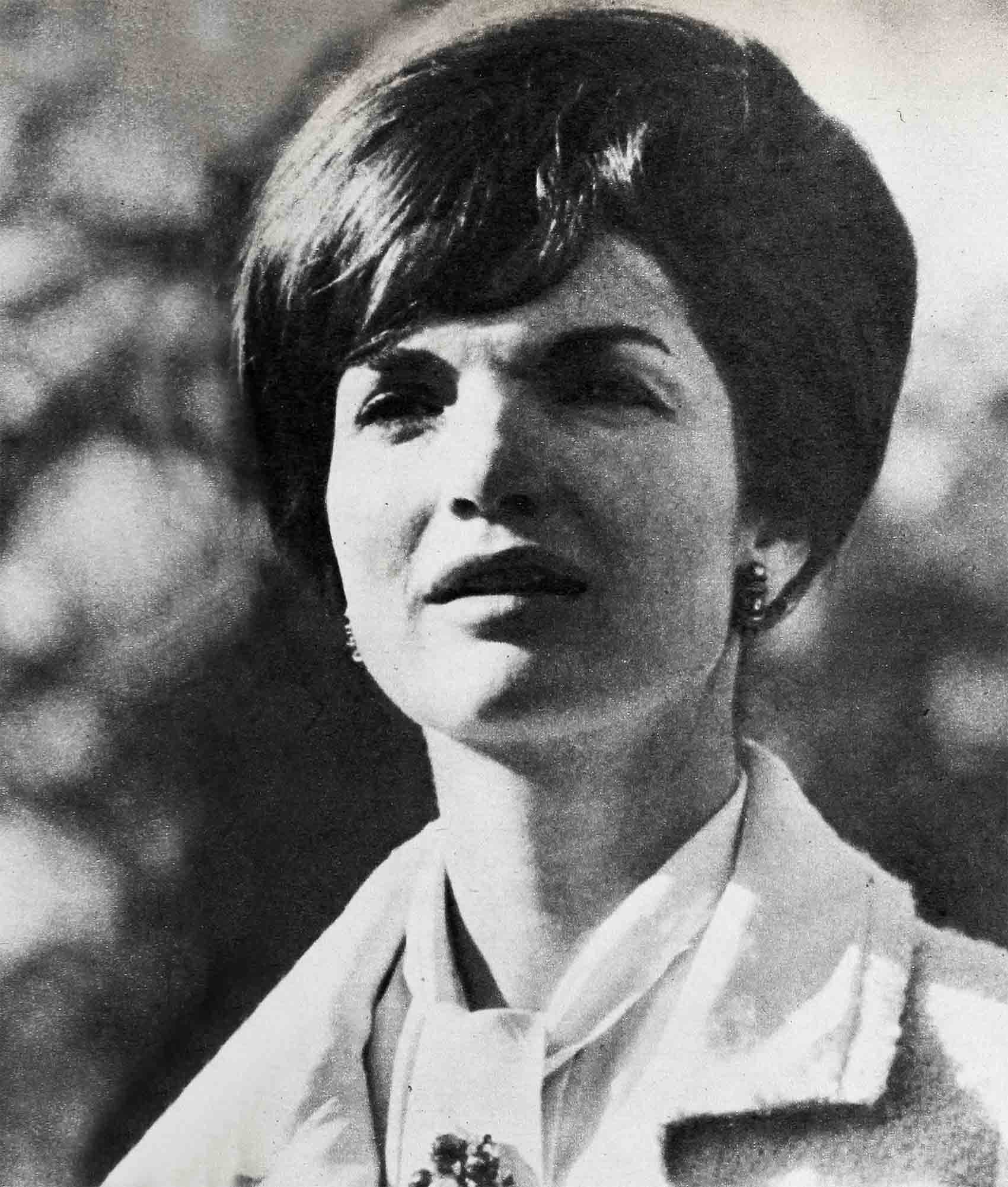

The woman was Jackie’s good friend, Charlene Cassini, the wife of former society columnist Igor Cassini, who under the pen name Cholly Knickerbocker had named Jackie “Debutante of the Year” in 1947—when she was eighteen years old.

And what had happened to Charlene Cassini was enough to make anyone weep.

Charlene had seemed dazzlingly lucky, at first; she seemed the kind of girl other girls envy. Born in 1927, two years earlier than Jackie, hers had been the same glittering world as Jackie Kennedy’s—a world of wealth and privilege, of sleekly groomed women and dashingly handsome men, people who never had to worry about where their next Rolls Royce was coming from. The world of the super-rich.

Truly, if anyone had ever been born to a golden life of wealth and luxury, it was Charlene. Her father was oilman Charles B. Wrightsman, one of the richest men in America and a close friend of Jack Kennedy’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy. The two men have mansions near each other on Palm Beach’s North County Road.

But the gold began to tarnish a little when Charlene was only ten. Her parents were divorced, and Charlene was sent away to school. She attended the exclusive Fox-croft and Ethel Walker schools, with other rich girls like herself. (Jackie Kennedy, too, would soon see her parents divorced and be sent away to Miss Porter’s school in Farmington, Connecticut.)

While Charlene was attending Finch College in New York, her father married again. This time his bride was a beautiful model named Jayne Larkin, who was just two years older than Charlene. Charlene’s own older sister, Irene, had married Freddie McEvoy, a dashing, wealthy sportsman who was a good friend of Errol Flynn’s.

At that time Errol, like other stars, was still fighting World War II—on the Warner Brothers sound stages in Hollywood. And the man who usually wound up on the other side, as a darkly handsome Nazi with traces of good in his character, was debonair young Helmut Dantine. Dantine scored a certain success in Hollywood, but when the need for men to play handsome Nazis petered out, his screen appearances became necessarily somewhat less frequent.

Married at twenty

Eventually Charlene met and fell in love with Helmut. By now, she had blossomed into a strikingly beautiful brunette not too different in appearance from Jackie Kennedy. And in 1947, when Charlene was twenty, she and Helmut were married.

But once again the gold began to tarnish. She and Helmut soon began having problems. And even though a son was born to them still the marriage unhappily failed.

So they were divorced in 1950. And the divorce wasn’t the “friendly Hollywood kind.” Far from it. Charlene charged that Helmut had married her “only for the money that I expected to receive from my father.”

There is no more bitter and humiliating feeling for a woman, particularly a rich woman, than the conviction that someone has married her for her money. And for Charlene, the bitterness did not fade with the passing years. For when she drew up a will years later, she inserted a strict provision that Helmut “should not at any time” be given custody of their son, Dana, who is now fourteen.

For a while it looked as though Charlene wanted to turn her back on that “golden life” to which she had been born. Although she had more money than she could possibly need, she entered a secretarial school in West Palm Beach, attended classes faithfully, and was delighted when she managed to earn excellent marks.

Perhaps she was beginning to envy those whose lives were humbler, simpler—and happier—than her own.

But soon her old life made its claim on her again—this time through the person of Igor (“Ghighi”) Cassini, to whom society was everything. They met and fell in love, and in 1952—after Ghighi had been divorced from his second wife—they were married.

Igor Cassini was the Russian-born son of an authentic Count, and therefore entitled to call himself a Count as well, until he obtained his U.S. citizenship in 1940. But in spite of his former title, lie was something of a self-made man. After unsuccessfully trying to make his fortune by selling things like insurance and cold cream from door to door, he got a job writing about society for the “Washington Times-Herald” (with a little help from his mother’s connections), and then became the Hearst papers’ Cholly Knickerbocker, top society columnist in the land, with a claimed readership of twenty million.

Some might have called Igor a social snob—particularly those who only knew him through bis television program, “The Igor Cassini Show,” which was on NBC Television from 1952 to 1955 and on Dumont for a year after that. His smooth manner of speech, his manner of dropping what seemed like whole telephone books of names of the socially elite—all seemed to make his whole TV show a study in snobbery.

But Charlene had a way of seeing only the best in people, particularly the men she fell in love with—even though she might come to regret it later. And there was no denying that Ghighi had charm.

Through Ghighi—whose naming of Jackie Bouvier as deb of the year had endeared him to Jackie at a time when she was choosing the friends she would carry through life—Charlene, too, became friends with Jackie. And, when Jackie married Jack Kennedy, she became friends with Jack, too.

In fact, Jackie’s marriage strengthened the ties between her and Charlene. For it made Jackie a frequent visitor to the Palm Beach home of old Joe Kennedy, a stone’s throw away from the home of Charlene’s father. Jack and Jackie began going to parties at the Wrightsmans’ house, and Jackie became particularly good friends with Charlene’s vivacious young stepmother, Jayne Wrightsman. Ghighi and Charlene were frequently at the Wrightsmans’ house, too, so it was natural that they should become even better friends with the young Kennedys. In the days when Jack was making his name as a Senator, and spending long weeks on the road building his chances for the Presidential nomination, he particularly cherished the brief opportunities he had to relax in Palm Beach with fun-loving people like the Wrightsmans and Cassinis.

Jackie and Charlene had much in common besides their upbringing. Both had enjoyed brief flings at being “working girls”—Jackie as an inquiring camera girl with the “Washington Times-Herald,” where Igor had gotten his start, and Charlene at secretarial school, even though she hadn’t gotten to use her proudly-won abilities as a secretary; both were excellent horsewomen; both loved parties and the conversation of bright, witty people; both loved children and were devoted to their own.

With Charlene’s stepmother, too, Jackie had much in common. Each had exquisite taste in clothes (Jayne Wrightsman has made the latest best-dressed lists, which of course are topped by the name of Jacqueline Kennedy). And each is interested in antiques (Jayne has assisted Jackie in the redecorating of the White House and gone on antique hunting expeditions with her).

The Cassinis were “in”

When Jack Kennedy became President of the United States, he indirectly helped enhance the reputation not only of Igor Cassini but of his brother Oleg, who is Jackie Kennedy’s official dress designer. Oleg found himself with more work than he could handle, designing clothes not only for Jackie but for all the wealthy women who wanted to be able to say that their clothes had come from the First Lady’s dress designer. And Igor was more “in” than ever as a society columnist, thanks to his friendship with the Kennedys.

On a number of occasions Charles Wrightsman lent bis Palm Beach mansion to the President and Jackie during their Florida visits. And even when they were staying with Joe Kennedy, they saw a lot of Igor and Charlene. Often when Jack was busy on matters of state, the Cassinis would drive up to the door of the Kennedy mansion and Jackie would hop into the car and join them for a relaxing evening on the town.

On New Year’s Eve, it was customary for Jack and Jackie to spend the evening at the Wrightsmans’ house, where a gala party was held. And on the eve of New Year’s 1962, Jack Kennedy did something that made the evening forever memorable for Charlene’s stepdaughter. Igor Cassini told about it recently in Good Housekeeping magazine.

“Jackie Kennedy danced with her husband, her host, with me and with most of the other men at the party. Then, at one point, she went over to the President, put her hand on his shoulder and directed his gaze to the terrace. There, standing with her face pressed against the windows of the French doors leading to the living room, stood my thirteen-year-old daughter, Marina. The President, perhaps thinking of Caroline in years to come, smiled at his wife and bent down to whisper a few words to her, She gave him a quick hug and watched him walk outside to where Marina stood.

“ ‘Would you,’ the President said courteously. ‘care to dance with me, Marina?’

“And inside they went, dancing slowly to the music but chatting away as if this happened every day.”

A year later, Marina would need the memory of that magic night to see her through the tragedy that clouded her life. . . .

Disaster had already begun to close in on Charlene Cassini, touching not only her life but those of her family—Igor, Marina, Dana, and Alexander, the son of her marriage to Igor.

First Charlene’s health began to fail. A few years ago, while she was skiing in Vermont, she suffered a painful leg injury that put her on crutches for a while. Even afterward, the leg kept troubling her. Again and again, there was the pain, coming when she least expected it. And then, last year, while she was standing on a stool changing a light bulb, her leg buckled under her and she went crashing to the floor. Her nose was broken and she suffered a concussion. Her health was never the same again. From that time on, her life was made miserable by blinding headaches. All her money, she found, could not buy her good health.

When we are ill, we desperately need to have life be kind to us, if only to give us some measure of consolation for the treachery of the body. But just when Charlene needed kindness from life, she got heartbreak.

It all started because of a public relations firm with which Igor was involved—a firm he had named Martial after the first letters in the names of Marina, Tina (Oleg’s daughter) and Alexander Cassini. In January of this year, the Saturday Evening Post published an article which pointed out that many of the clients who paid fat fees to Martial got mentioned in Igor’s Cholly Knickerbocker column. But this slap at Igor’s journalistic ethics wasn’t the most damaging part of the story. What hurt was the fact that the writer traced a series of business and personal connections between Martial and other firms and people which convinced the writer, at least, that Igor was an unregistered representative of the Dominican Republic.

Now, the U.S. Government has strict rules that all foreign agents must register. And, as a matter of fact, Igor was registered with the U.S. Government as a foreign agent—but for Mexico and Brazil, not for the Dominican Republic.

If Igor had failed to register properly, he was liable to a hefty fine and a jail sentence.

Up to that point, Igor was only confronted with an embarrassing magazine article. But then the roof fell in. Bobby Kennedy’s Justice Department had been investigating Igor, too (there was, of course, no thought of “going easy” on him because of his connections with the Kennedy family), and as a result of the Justice Department’s investigations, a federal grand jury indicted Igor on charges of failing to register as an agent of a foreign government. His trial was set for May, and the Hearst papers put him on “leave of absence” from his column.

Along with four other men, Igor was accused of sharing $200,000 paid by the regime of slain dictator Rafael Trujillo. All four had been associated with Martial.

Reporters noted publicly that Igor had accompanied former Under Secretary of State Robert D. Murphy to the Dominican Republic six weeks before Trujillo was assassinated in 1961. This visit was made at the request of the White House after Igor had “warned” U.S. officials at his father-in-law’s house that the Communists were plotting to overthrow Trujillo. (His actual killers were disgruntled military men of his own country.) And it was also noted by reporters that Igor had mentioned Trujillo and his country very favorably in his widely-read newspaper column.

Pain and embarrassment

To Charlene, not only were these charges against her husband painful—she must have also been embarrassed for Jack and Jackie Kennedy, who were her friends.

What was worse, friends watching the situation became convinced that Charlene’s father, Charles Wrightsman, at whose home Igor had “warned” Government officials about Trujillo’s “enemies,” was more than embarrassed. The friends believed that Wrightsman’s attitude toward both Igor and Charlene cooled considerably after the public charges.

And so Charlene found herself an embarrassment to her friends in the White House and, apparently, an embarrassment to her father as well.

To a sensitive young woman who gave her love and friendship generously, and who asked only that these be returned to her in some measure, it was a cruel blow. Loyally, she stood by her husband, but her heart was heavy with shame and grief. She could only be grateful that Jackie Kennedy gave no signs of turning against her old friend despite what Bobby Kennedy had had to do. But at the same time, Jackie’s loyalty made Charlene’s embarrassment even more piercing.

Then came one more blow—a blow of the kind that can affect the mind with peculiar cruelty when it is already reeling from other misfortunes. A close friend of Charlene’s, thirty-five-year-old Peter Estin, a Vermont ski instructor, was found dead in a New York hotel room of what the coroner described as “visceral congestion.” One of the causes of “visceral congestion” is the consumption of a deadly amount of sleeping pills. His funeral was set for April 8th.

Charlene didn’t go to the funeral, which was held in Boston. But Igor did—and, ironically, he flew in the private plane of George Skakel, who is Bobby Kennedy’s brother-in-law. Igor returned that evening to the apartment he and Charlene shared at 944 Fifth Avenue, across from Central Park. For he and Charlene were scheduled to attend a dinner party, and Igor didn’t want to disappoint their hosts.

But Charlene didn’t feel up to it—she gave a toothache as the reason. So Igor went on alone, and Charlene and her step- daughter Marina began watching the Academy Awards on a TV set in Charlene’s bedroom.

Charlene had been having trouble sleeping lately, and had been under a psychiatrist’s care. Her father and stepmother, realizing how hard Charlene was taking it all, had come up to New York to be with her despite any feelings Charles Wrightsman may have had against Igor. And that very day they had spent several hours trying to talk Charlene out of her depression. But she was inconsolable.

That evening she had sent Marina out to the drugstore to get her a new bottle of sleeping pills which the doctor had prescribed. And now, with the Academy Awards program starting, Charlene got up from her bed and went into the bathroom. Then she returned and lay down on the bed again, as Marina sat nearby, absorbed in the show.

Marina watched the Awards through to the very end. Then she turned around and looked at Charlene—and saw immediately that something was very wrong. Terrified, she called the doctor.

Igor arrived home just in time to accompany Charlene to the hospital. By now she was unconscious. And as doctors at the hospital fought to save her life, the sleeping pill bottle lay empty in the Cassini apartment. Earlier that evening it had held thirty pills.

All through the long night the physicians worked over Charlene’s still, silent body. But it was too late. By morning she was gone. A girl who had been born to the beautiful, golden life of the rich had watched that life turn black and ugly before her eyes. She had seen the men she loved bring her unhappiness; seen herself become an embarrassment to her friends; seen herself destined to spend her days in a sleepless agony of blinding headaches and heartsick humiliation. In the end, it had been too much to take. All she could do was hope that her friends would remember her kindly. . . .

In the White House flower garden, on the day of Charlene’s death, Jackie Kennedy did remember—she remembered, and tried to hold back the tears. Tears of heartbreak for a friend who had died too young.

No, she mustn’t cry any more. There were too many people watching, and it was an important occasion of state. Tears were a luxury that no First Lady could afford in public.

It was important to think of other things. Surely, even today, there must be something to be happy about. . . . And of course there was. Stirring within her was a wonderful secret of her own, a secret the whole world would soon come to share—the secret of a new life, with all the hope that new life brings.

Yes, better to think of that, and to look to the future. For the recent past was too sad to bear.

—JAMES GREGORY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963

vorbelutrioperbir

4 Temmuz 2023Hello are using WordPress for your site platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you need any html coding expertise to make your own blog? Any help would be greatly appreciated!