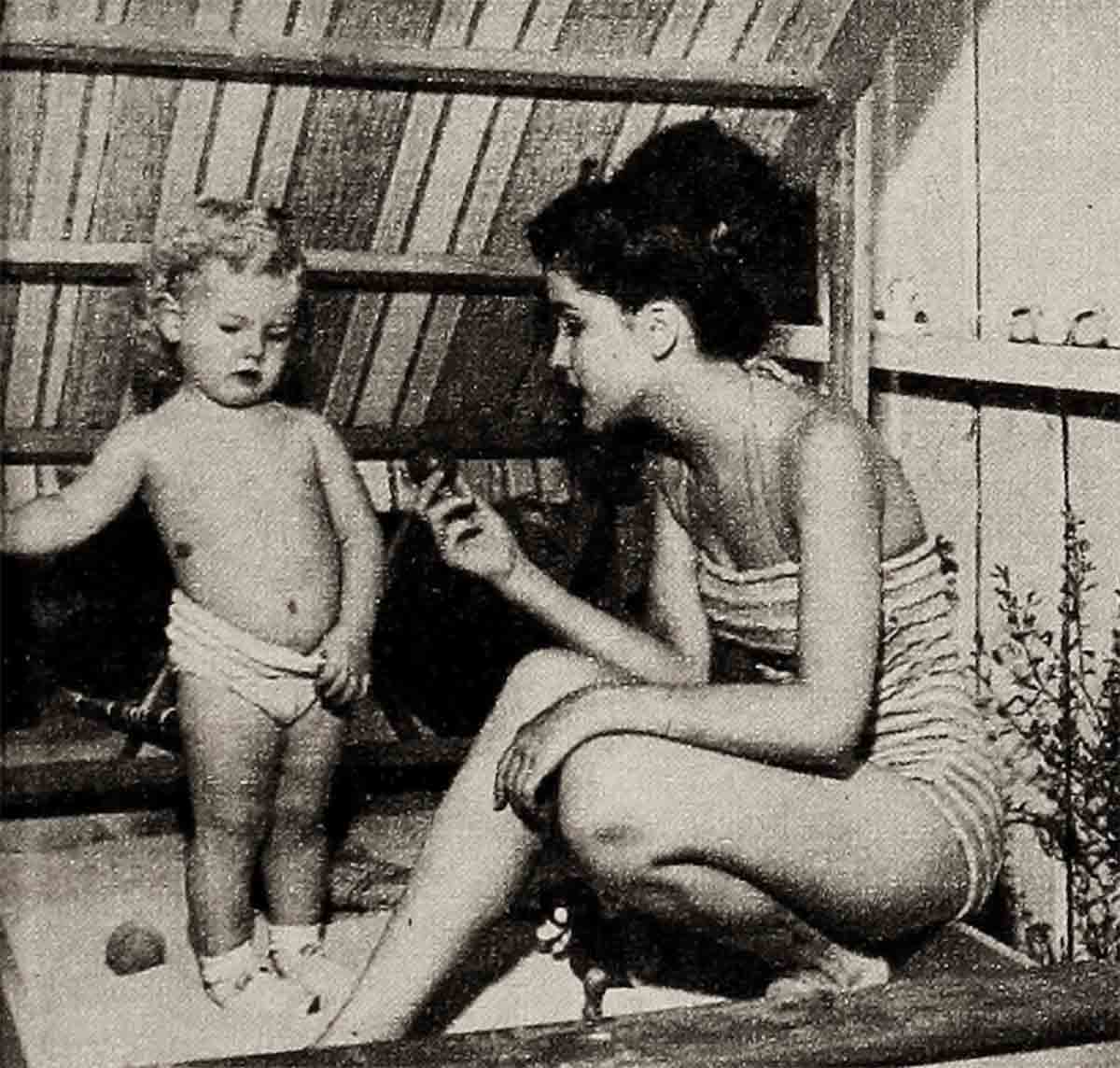

Does Mother Know Best?—Debra Paget

You should watch Debra Paget’s eyes sometimes when anyone suggests that she is still a mama’s girl. They can slant down to the thinnest, unfriendliest tilted slits you ever saw. She might say a few cold words in denial, or, even more likely, do it with an even colder silence. She particularly resents such insinuations from boys. One such fellow talked along this line when trying for a date the other day. Not an effusive girl anyway, Debra gave him a look that told him exactly what to do but he refused to drop. He managed to stay on his feet, and alive, while she marched away. He wouldn’t have gotten the date anyway, very likely, but if he had been more diplomatic there might have been an invitation to join the gang at her home some evening.

It is difficult to picture Debra as a meek and obedient daughter when you study her full-blown beauty, catch the flaunting fling her curvacious figure can achieve when she walks down the street in a bright ballerina skirt, the woman she can be or see in one of her romantic screen roles. Even three years ago when Debra played opposite Jimmy Stewart in Broken Arrow her femininity seemed lacking nothing in maturity. Jimmy turned way once from a clinch with Debra to mutter to Delmar Daves, the director, “You can’t tell me that this girl is just 18.”

“She isn’t,” Delmar agreed. “She isn’t even 16 yet!”

The whistle which came from, Jimmy Stewart’s lips at that rejoinder has been echoed admiringly many times since, but also despairingly by would-be boy friends who always find themselves getting nowhere in their attempts to get anywhere with her. Just to catch a few minutes alone with Debra is something practically none of them can boast about. Debra may be 19 today but it is still one of Hollywood’s rarities to see her anywhere without her mother, Mrs. Margaret Griffin.

In fact, if Debra should ever be asked that standard courtroom query, “Where were you on the night of (or the morning of, or the afternoon of) . . . et cetera?” she can always tell the truth by replying, “With my mother.”

Mother is with her when she arrives at the studio in the morning. Mother is with her when she leaves. In between mother is with her at make-up, hair-dressing and every minute on the set. Mother is there at conferences, at luncheon, during interviews. Mother is not only always there but except for the moments when Debra is actually in front of the camera mother does most of the talking. It is getting so that people who ask Debra a question automatically turn to mother for the answer.

Thus her professional life. Ditto her personal life. It is spent mostly at home with her sisters and brother, their friends, and, of course, always mother. On those occasions when she attends a party (usually one which has publicity implications or is otherwise blessed by her studio) it is always with the same combination escort-chaperon and shadow . . . mother. On arrival, mother’s presence is sometimes resented by the host, hostess or guests, but she is so breezy, so full of easy cameraderie, that before long she is hailed as the life of the party. The joking and the laughter centers around her; Debra, the star, the celebrity, is content to sit quietly by, basking in her mother’s temporary popularity.

Actually, since the days of Shirley Temple, whose mother left no doubt that she, and only she, made Shirley’s decisions, Hollywood’s screen mothers have tended to stay in the background of their children’s careers. Mrs. Griffin is one of the few exceptions to the rule. Another was Margaret O’Brien’s mother, Mrs. Gladys O’Brien, who once declared, very emphatically, that “A movie child is a child who does as she is told, immediately, the first time.” (This was some years ago when Margaret was her studio’s prize possession. Nobody seems to know what to tell Margaret these days.) But the mothers of such contemporary stars as Barbara Ruick, Terry Moore, or Debbie Reynolds, for instance, are not at all inclined to such an attitude.

Terry Moore’s mother, Luella Koford, the writer, is mainly concerned with how Terry is represented to the public; she simply wants to be of use to her daughter and the best way she can accomplish this is by giving Terry the benefit of her own experience in public relations. “I’ve done nothing since Terry has been in pictures but watch out for her art,” she said not long ago, referring to exerting a restraining influence on Terry’s bathing suit pictures in general, and a couple of flesh-colored ones in particular. “I realize the need for sexy art but there has to be a stopping place somewhere.”

Mrs. Maxine Reynolds, mother of the bouncing Debbie, is a natural homemaker and has refused to let her daughter’s prominence interfere in any way with that most important and warming duty. And as far as Barbara Ruick is concerned she has had parental carte blanche to live her own life practically all her life. As a tot she was permitted to meet the guests when her folks gave parties and show off by reciting for all “with gestures.” The guests used to get sick of it, the story goes, but Barbara did acquire a self-confidence and poise that has stood her in good stead before the public. Her mother, Lurene Tuttle, how acting in radio, and her father, Mel Ruick, of the New York stage, have since been divorced, which, of course, has minimized whatever home influence Barbara might have had. Yet her mother approves of Barbara’s independence, of her right to make her own decisions no matter whether these involve going off on USO trips or accepting or rejecting the kind of social or professional life she wants to lead. “Barbara can take care of herself,” Lurene says.

Debra’s mother has actually said these very same words in talking about her. But while she may speak the lines of a modern Hollywood mother, she doesn’t play the part. She insists, “The only reason I am with Debra a lot is because Debra wants me around.” And Debra always nods in confirmation.

Mrs. Griffin goes even further. She tries to play friend to every boy who wants her to speak a good word for him with her daughter. She has never been known to discourage one; she gives every evidence of enjoying being known as a good sport. She even seems to make a practice of being heard arguing with Debra along this line. “Soandso’s a nice kid,” you can hear her tell Debra about some fellow. “If I was your age and unmarried I’d love to go out with him.” Debra seldom replies.

Is it an act?

A reporter once asked Mrs. Griffin about this. (Debra was right there, sitting dutifully alongside her mother as always.) “You say that Debra has all the freedom she wants, if she wants it. But isn’t that just a picture you are painting?” he wanted to know. “Isn’t it true that you never let her out of your sight?”

“Oh, somebody’s been kidding you she scoffed. “Who have you been listening to? I’m not straight-laced. Why, I married when I was three years younger than Debra is right now. It’s just Debra’s way. She is more interested in her work than anything else right now, that’s all. Tomorrow it might be different. Even her sisters rib her about it all the time; keep telling her she’s a natural old maid type.”

Debra was already nodding in agreement. No reporter can recall any instance when she and her mother ever disagreed—not in public, that is.

The one outstanding truth about Hollywood mother-daughter relationships, an almost unvarying fate, is that they cool; the thicker the pair, the more prominent the star, the quicker and more solid the frost. The latest case involves Elizabeth Taylor and her mother, Sara. It’s sad but it is true. Mrs. Griffin is not unaware of this; no one in her position could be, Maybe it was fear, maybe she was kidding, when she said once, “If Debra gets uppity I’ll sit on her.” Maybe she was kidding because she weighs close to 180 pounds and doesn’t mind joking about her plumpness. But she is so much a part of Debra’s affairs that it must be frightening to her to contemplate the day when she will have nothing to say about them. In Debra she lives again the thrills and great moments she once knew herself on the stage. When that is taken away from her . . . ?

Debra always explains her preference for her mother’s company along personal lines. She says she has Victorian ideals about romance and is not interested in being with young people just for the sake of getting around. “I’m a firm believer in love at first sight,” she has said. “Until that happens I have no intention of dating even casually. Being with my mother, my family, is much more enjoyable to me than being in the company of some man in whom I have no permanent interest.”

Some boys who have tried to get to know her, and failed, don’t think she has told the whole story here. “It’s hard to believe,” said one, “but there is a lot of little girl in that big girl.”

However, there are friends of the Griffins, studio people close to them ever since Debra got her movie start at the age of 13, who have a more simple explanation for Debra’s loyalty to her kin.

“Her parents have a tremendous investment in Debra,” said a woman who is associated with Debra’s rise to stardom. “It is an investment not only in money but in the sacrifice and hardship that any family finds it must undergo to finance the career of a beauty. Why even after Debra starred in several pictures the principal source of support for the family was not her salary but the steady wage earned by her father as an ordinary painter. Only three years ago Debra was getting $100 a week, with a take-home pay, after agent’s commission and all other deductions, including court-ordered savings, of hardly $40 a week! Even now, with a salary of $500 a week a surprisingly small part of it can actually be used for upkeep. The family is still paying off for her first good fur.

“Debra realizes all this. She saw the penny-saving that went on, the scrimping that meant, and still means, living in small, cramped homes, and she wants to make sure that all this effort is justified. And it’s because she doesn’t want to make any mistakes that might jeopardize this goal, in her personal life as well as her professional one, that she wants the benefit of her mother’s judgment always.

“Some people think her mother is folishly trying to shield Debra from contact with life. They forget Mrs. Griffin was on the burlesque stage for years and that Debra was raised in as raw an environment as you can find in this country. Even if she tried, her mother could hardly keep her in ignorance of life, and she doesn’t try. Nor is Debra ignorant. She isn’t afraid of unknown pitfalls; it’s the common mistakes she doesn’t want to make; the ones any young actress knows about and can still trip over. That’s where Mama comes in—to help Debra make sure.”

There is no doubt that Debra is a serious girl. A good proof are all the “A s” she got as a studio scholar, snatching her lessons on the set between acting sessions. Schooling doesn’t come easily this way, as any educator will tell you; there are not only too many interruptions, there are too many glamours distractions.

Everyone around the Fox studios remembers a weird algebra answer Linda Darnell turned in early in her career when one afternoon she was summoned to class by her teacher right after a tempestous love scene in front of the camera. Linda finished an equation by writing that “X” equals “TP.” It seems she was still thinking of Tyrone Power, whose arms she was just left.

Debra has impressed her teacher with her power of concentration. Once, during some location shooting in. New York she had to take an examination in a publicly parked taxicab which the studio had rented for a classroom. Again she got her “A.”

Oddly enough, Debra may be getting some freedom soon from mother’s supervision whether she wants it nor not. One of her sisters has become a screen hopeful at another studio. Some weeks ago Universal-International developed a strong yen to have Debra co-star for them with Donald O’Connor in Walking My Baby Back Home. They had a tentative talk with Debra (and mother) and were told that 20th had an exclusive contract.

“But why don’t you try my sister, Lezlie Gae?” suggested Debra. (If you like the name Lezlie Gae you might as well know that in the Griffin family colorful names do not happen by accident. Mrs. Griffin, with show-minded foresight, christened all her children with names she thought would look good on theater marquees. Debra’s full name, for instance, is Debra-lee. Another grown daughter, now married, is called Teala Loring. Then there is Debra’s older brother for whom Mrs. Griffin really reached high, wide and dramatic. He is known as Ruell Shayne.)

The studio took a look at Lezlie Gae and liked her very much. She didn’t get the role offered to Debra but she is off to a good start. The only trouble is that which looms ahead for Mrs. Griffin. Universal-International is about ten miles from 20th Century-Fox. She can’t be in two places to watch two daughters!

So maybe some changes are in order. But as of this date Debra and her mother, are still a going concern. Even when night falls, and Debra pulls back the luxurious, red velveteen, quilted spread over her extra-sized bed and prepares for sleep . . . mother is still there. They even share the same bed!

THE END

—BY ALICE HOFFMAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1953

No Comments