Tony Curtis: “Now I Can Talk”

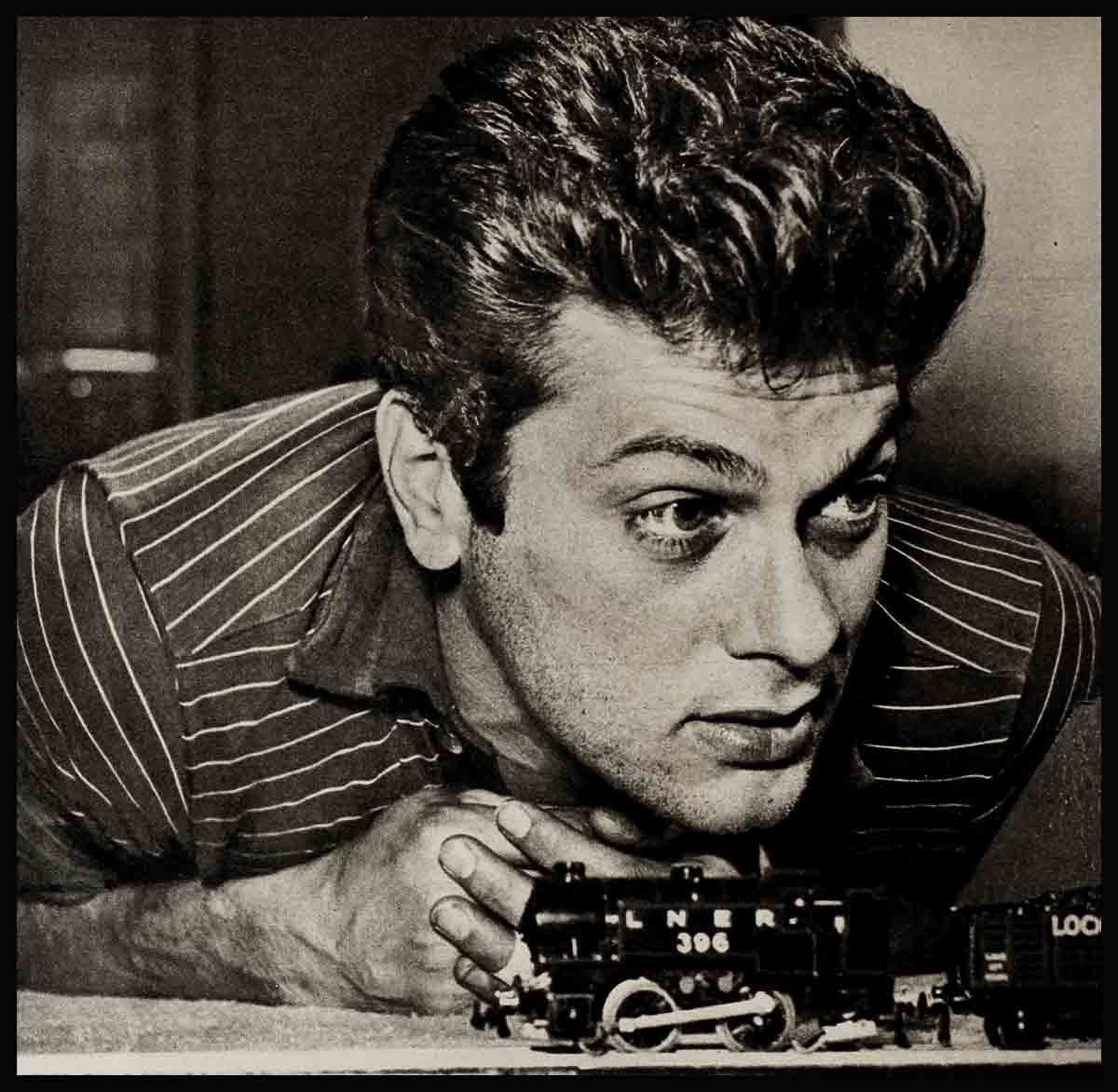

The Tony Curtis-Janet Leigh living room was like Grand Gentral Station, complete with train, when I arrived at their Wilshire Boulevard apartment for an interview one recent Saturday morning. Janet had gone off to work at MGM in Fearless Fagan, the phone was ringing, the maid was cleaning up the breakfast dishes—and Tony was eating an orange while playing with a new electric train that had arrived from Europe that very morning. You heard me—26 years old, and a movie star, and playing with an electric train. And one that he had bought

for himself, not for his kid brother. I ignored it and begged for coffee. Tony made a potful.

Every other magazine writer in town but me had interviewed Tony, yet I had known him longest. I was, in fact, the first Hollywood reporter ever to write a line about him. That was four years ago, when he first arrived from New York, a wide-eyed, scared, naive unknown. I had met him, announced his arrival in my column in a Hollywood trade paper, prophesied a successful career for him and then continued writing about his activities while other columnists ignored him.

Anyway—here I was now. And there was that train. This was a new side of Tony. Maybe I didn’t know him so well after all.

“I thought I’d write a story about you and call it ‘Now I Can Talk,’ ” I said, after he got off the phone. “Something that’s never been touched on in your other interviews. Something . . .”

The phone rang again. It was his mother. He excused himself, talked to her lovingly for ten minutes, excused him self again after he hung up, and said, “We’ll only have a few more disturbances, I promise you. Janet will call once or twice, when she gets a break, and that’s all.

“See this train?” He was playing with it again, making it back up. The engine leaped off the track, scattering the coaches right and left. “I didn’t have one when I was a kid,” he said. “This makes up for it.”

His present life is making up for a lot of things he didn’t have as a kid. He had been afraid of people. He knew he spoke the dese-dem-dose lingo of New York’s Lower East Side, and he was afraid people would criticize his speech.

“But I’ve gotten over that,” he said. “I’ve found that people don’t like you because of the way you speak or cut your hair or turn your collar. They like you if you want to be liked.

“I didn’t know that when I was a kid.” He threw the switch again and the train tore down the track. “I neededfriendship, too, but I never had it. And you know something? I still need friendship. Everybody does. That’s why Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin and I started the Gar-Ron Club, which is a combination of the names of Jerry’s children, Garry and Ronnie. We make home movies, shoot pool, play golf and tennis, swim, go off on picnics—all that kind of jive.

“Well, I came to a brand new place—Hollywood—and I wanted to be liked. Somebody at U-I once told me, ‘Kid, I want you to go out and pick me up a right-handed punching bag.’ Well, I knew there’s no such thing but I went out and pretended to look for it anyway. Why? Because this is a strange new place to me, and I don’t know these people too well, and if one of them enjoys this kind of thing at my expense it’s the least I can do to gain his friendship.

“Should I go up to him and say, ‘Who are you trying to shove around, wise guy?’ Of course not. If this is the kind of thing this guy does for kicks, let him have his kicks. And if another actor makes fun of the way I talk, let him be my guest. Let’s all enjoy ourselves. You know something? It’s a small price to pay for a little affection, love and friendship.”

I had known all this about Tony long ago, when he hadn’t been able to express himself on the subject so well. Humility is a basic trait with him.

“My business is acting,” Tony continued. “I want to do it more than anything else in the world, and do it well. I knew I was limited, at first, because I talked out of the corner of my mouth, and this made me afraid. Suppose I had gotten temperamental when the breaks started coming my way, and coming, miraculously, despite my defects? Suppose I’d started throwing my weight around, like some stars do? Then the people at the studio would have started talking behind my back and the next thing you know columnists would have been printing stories about an incompetent so-and-so like me kicking up his heels and I’d be through. No, one fault was enough, without piling another on top of it.

“Then I met Janet. Because she loves me, and because I love her, I have the security I lacked when I was a kid. I’m able to go to work in the morning now and not be afraid.”

“Afraid? I never suspected it,” I said.

“It’s true,” said Tony. “An accent is a tough thing to iron out. But Janet has given me self-confidence. I know that whatever happens to me from now on, whatever calamity befalls—if people don’t go to see my pictures or if nobody comes to interview me for a movie magazine, or whatever—that my wife will always be there when I come home at night, and she’ll kiss me and say, ‘Come on in, Tony, and have dinner, and then we’ll watch the fights on TV, or you can play with your train.’

“Security is what does it—the security of a loving wife, of a home, and of friends. That’s what really counts.”

Then all of a sudden it was 1941—eleven years ago!—and Tony was 15 years old, and he and I were in a factory in New York City. He was acting it all out for me, and, although this Saturday morning of our interview was a coolish one in Westwood Village, I could feel the heat of that sticky, humid summer afternoon on the Lower East Side and see and smell the grimy factory in which Tony worked.

“I had been a counselor at a camp in the Catskills earlier that summer,” he said, “but the job didn’t pan out for some reason or other—I really don’t remember exactly why—and I got back to New York broke. I had to have a job. I read the want ads. One said, ‘Boys wanted between 15 and 18 for summer work.’

“It was a broom factory. They picked six of us out of a big gang of kids and put us to work for $12 a week. My job was to stand at a high desk-like machine and run the uneven brushes through a cutter as they came off the assembly line, to even them off. The cutter jabbed away at my knuckles and nails and made them bleed.

“It couldn’t get hotter than it was in that place. I was drenched with sweat—and blood! But the foreman watched us like a hawk, and if we took a break and stayed away for a few seconds longer than he thought was absolutely necessary he would poke us in the back of the neck when we got back and snarl, ‘Whaddya think we’re running around here—a kindergarten? Keep workin’, kid, keep workin’.

“Nights, when I got home, I was ready to kill anybody or anything. I could still feel him poking me and telling me to keep working. I got to hate that man.

“And yet, now that I look back at it, I’ve got plenty to thank him for, too. I think if he was around now I’d give him five percent of my salary, because he provided me with a drive—a drive to better myself. Some impulses are based on hate, I guess, and maybe it’s healthy and maybe it isn’t, but that foreman—and, I suppose, my environment—prodded me into trying to make something of myself. Whether Ive achieved something big or not is another question, of course, but you’ve got to admit I’ve bettered myself—at least to the extent of making $400 a week against that original $12. And it’ll be much more soon, I hope, because I’m due for a raise. But $400 isn’t an awful lot, all things considered, is it? Only $230 of that is take-home pay. The rest goes for taxes. And I give my folks $100 a week and live on $130. We live frugally, Janet and I, as you can see. But it’s still a lot better than a cold water fiat and a factory, isn’t it?”

I had to agree. The phone rang. He answered it. “Hungarian Underground!” he announced. “Janie? I love you I love you I love you—”

The words rushed together, just like pee No periods, and accent on the word “love.” I got out of the room while he talked to his wife, although he beckoned me to stay.

When he called me back in, five minutes later, he said, “She loves me too. Where were we? Oh, yes—

“I’ve just finished making Flesh and Fury at U-I. I play a deaf mute boxer. Joe Pevney, who used to be an actor, directed it. And, because he was an actor, he inspired me. He’s not the kind of director who worries about camera angles. Instead, he sat me down before each scene and gave me a reason for everything I did. As a result, I didn’t stand around looking dopey like I’ve done in other pictures. I’ve enjoyed this one more than any of the other pictures I’ve made because of him.

“I got such a shock when Joe would say, ‘Tony, how do you feel about this scene?’ I got chills up and down my spine because I kept thinking, I’m being considered—I’m being asked for my opinion! Mama, you should only be here and see what’s happening! Somebody is asking for my opinion— and eleven years ago I was working in a broom factory! It breaks down to $600 a minute to make a picture, and Joe Pevney is taking time out, Mama, to ask your little Tony’s opinion!’

“I met a lot of established actors when I first came to Hollywood. Some of them fluffed me off and I was hurt because, as I said in the beginning, I wanted to be liked. But then I kept getting better and better parts. And those same actors don’t fluff me any more.

“Nowadays I run into kids who are just starting in the business and they seem to be afraid I’m going to fluff them too, but I don’t. I make it a point not to. And please don’t make me sound conceited. when you write this. Naturally, I don’t go out of my way to fawn on people, because I’m no different than anybody else. You can’t like everybody. Nobody can. But when I meet some young actors that I like I try to be nice to them, just as I hoped those established actors would be nice to me three or four years ago.

“I think I can truthfully say I’ve never been envious of anyone. I’ve found it difficult enough to worry about my own personal life and development as a human being and my career without worrying about six other actors and how they are doing. If they do well, more power to them. This is what they want, and let me sidestep here a little to say that my favorites of them all are Marlon Brando, for his uninhibited wildness and because people see him in movies and wish they could go up to their bosses and tell them where to get off like Marlon does; Cary Grant and Laurence Olivier, because they’re such great artists and make it a real joy to watch them; and Jerry Lewis, because he’s the funniest performer in the world.”

Tony loves his folks inordinately, and they keep cropping up in his conversation. But now I was pinning him down about the people who had helped his Hollywood career most, and he said there were eight of them. “I’m not including my folks,” he said, “because—well, because this is the way they are:

“Before I married Janet I went to my father for his blessing, and he said, ‘Kid, I don’t care who you marry as long as you’re happy. Just be honest.’ How could you help but like people like that? So let’s stick to my Hollywood career. These are the eight people who’ve helped me the most out here:

“First, Janet, because, although she’s younger than I and hasn’t been around as much she’s, well, she’s the transformer of my electric train, let’s say. She motivates me. And she’s kind and considerate and understanding.

“Second, Jerry Lewis, who gave me confidence when I needed it. He kept saying, ‘You’ve got talent, Bernie. Work at it. Develop it.’

“Third, George Rosenberg, my agent, who loaned me money when I was flat broke but has never yet taken a cent of commission! I’ll pay him back, of course, when I’m making more money under a new contract that’s coming up. It’s not the studio’s fault that I’m not making more money. After all, they took me when I was an unknown and made a star out of me. My raises keep going right along, in the natural course of events.

“And George has done other things, too. When my father had a heart attack George saw to it that he had a private room in the hospital and took my mother to see him every day. He also bought me a TV set at cost, gave me a jacket, and called me into his office to encourage me whenever the going got rougher than usual.

“Fourth, Bill Goetz. People will say, ‘Well, Tony’s got to say something nice about Bill Goetz because Bill Goetz runs the studio.’ But this isn’t true. Bill called me into his office, too, to watch the World Series with him. And he came on the set and said, ‘Tony, if you have any little problem at all come and see me about it. You’re an important property here at Universal, your pictures are going over big, you’ve been a nice boy, and we appreciate it. Thank you very much.’

“How do you like that for the head of a studio? And when I pass him on the lot he calls out, ‘Hi ya, pal,’ and I holler back, ‘Hi, buddy.’ You know how tough it is to run a studio, but Bill Goetz has time to stop and say hello to everybody. He’s a real sweet, wonderful man.

“Fifth, Al Horowitz, head of publicity. He could push a lot of people but has picked me out and pushed my career tremendously. Another wonderful guy.

“Sixth and seventh, Leonard and Bob Goldstein. Bob discovered me in New York and Leonard, his twin brother, gave me my first starring role, in The Prince Who Was A Thief.

“Eighth, Sophie Rosenstein of the talent department. She worked night and day with me, helping me to straighten out my speech and giving me dramatic lessons.

“And those are the top eight. Now, you’ve noticed I’ve mentioned everybody who heads a department. But there are plenty of others, who hold less important jobs at the studio, who’ve helped me. Wonderful publicity people like Betty Mitchell, Jean Bosquet and, most of all, Frank McFadden, who explained to me at the very beginning all about the studio, how it works, what it’s like to be an employee in a big industry, the responsibilities not only to yourself but to the people you work with. And how, if something is upsetting you, you go to somebody in charge who can help you solve your problem and not take it out on somebody who doesn’t understand it, as I’ve heard some players are apt to do.

“Then there’s Sol, the studio barber, who lectures me while he cuts my hair. Things were going well with me one day and I was feeling cocky. He took a look at me and said, ‘Tony, you seem like a nice boy. And that’s important. But you know what, Tony? Something else is important too. Stay a good boy always!’ I’ve never forgotten that, because it seemed so important to Sol that things should stay good and nice in this tough racket.

“And Johnny, the cop at the gate. He let me sneak a friend from New York past the gate a few years ago. My friend wanted to see the back lot. Johnny showed me that even though you’re tied down by rules you can break one now and then for a friend, and none the wiser. This releases you and teaches you not to take your job too seriously.

“The boys in the studio gym have been true blue, too. Whitey Egbert, the trainer, has taught me that if you believe in something you should believe in it all the way. Don’t give up for anything. Here’s how Whitey is: if you’re arguing with him and he doesn’t like what you’re saying he puts up his hand to warn you to stop and then turns off his hearing aid. He has also taught me not to get too carried away with myself.

“And Frankie Van, who runs the gym, let me work on the cuff when I couldn’t afford to pay him $10 a month for using his facilities.

“Bob Laszlo is another pal of mine. He’s a prop man. He taught me to put things away. I used to leave props lying around and he would pick up after me. He said, ‘I don’t care how important a star you become, you’ve got to learn to be nice and put things away. The little things are important, Tony. Stars are important, sure. But the little guy who works behind the camera makes a big contribution, too, and all these things together make one picture. And I don’t care how smart you are, Tony, or how big you become, there are certain rules that a real person observes.’

“I’ve heard of stars who say, ‘What do prop men know about a star’s problems?’ They know plenty, believe me! They’ve been around a long time, longer than a lot of stars that you never hear about any more. Bob, for instance, came up to me on the set one day and said, ‘Tony, I saw you do that scene. It was very good. But don’t you think you should feel it?’

“He felt there was something lacking in my acting. And he was right! I had been doing everything else perfectly, but I hadn’t been throwing myself into the scene, feeling it like Bob knew, from long experience, I should be feeling it. And I was flattered that Bob had singled me out to share his knowledge with me.”

Tony was playing with his train again. It was nice to hear about the people he liked, I said. Now how about the people he disliked?

“Why lie about it? There are a lot of people I dislike,” he said. “I dislike the same percentage of people that any other normal human being dislikes. If I said I didn’t I’d be a liar.

“I dislike certain people for being vicious. That’s the unforgivable sin, in my eyes. I don’t like people who come up to me and say, ‘Tony, you were great in your last picture,’ and then knife me. It’s happened more than once, and when I know they’ve told somebody else I’m not so hot I look them right in the eye and say, ‘Why do you do this to me? You talk behind my back and then tell me how great I am to my face. Why?’ That stops ’em!

“Then there are the people who say, ‘Kid, the reason that certain deal worked out for you was because I put in a good word for you’—and all the time you know they’re lying. And the ones who never stop reminding you that you’d never be where you are if it wasn’t for them.

“Probably the most disheartening of all are some of your old friends who imagine you’ve forgotten them simply because you’ve become a star. Some of them actually seem to get a perverse delight out of the thought that you’re too important for them now. But when you’re with them and try to act as naturally as you did in the old days they accuse you of patronizing them.

“I got one letter from an old friend that illustrates perfectly what I mean. He was my closest boyhood buddy—in fact, my only buddy. We were so close that one day we cut our fingers with knives and held them together so that our blood mingled. We swore then and there that we were blood brothers for ever and ever.

“So what happens? I’m here two years and I get a letter: ‘Dear Tony—or should I call you Bernie?—I wonder if you’ll remember me?’

“It threw me off my feed for a whole week. People seem to think that if you’re a success the most important requisite is that you forget your old friends. Actually, they must think very little of you to imagine that just because you’re doing well you’ll forget them. Do I make myself clear?”

“Perfectly.”

He knit his brows and thought a while. “I’ve been very fortunate,” he said, finally. “And some day, if it ever blows up, I’ll think nothing of going back and opening a shoe shine parlor in the Bronx—if I can find a good spot and saying, ‘Okay, I’ve had it—I’ve touched success. And now I’m happy.’ ”

Janet phoned again, just then. The “I love you I love-you I love you” routine began. Then, “Okay, honey, knockwurst and beans for dinner, and you’ll cook ’em. I love you I love you I love you. Real crazy!”

He hung up with a smile on his face and winked at me.

THE END

—BY MIKE CONNOLLY

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1952