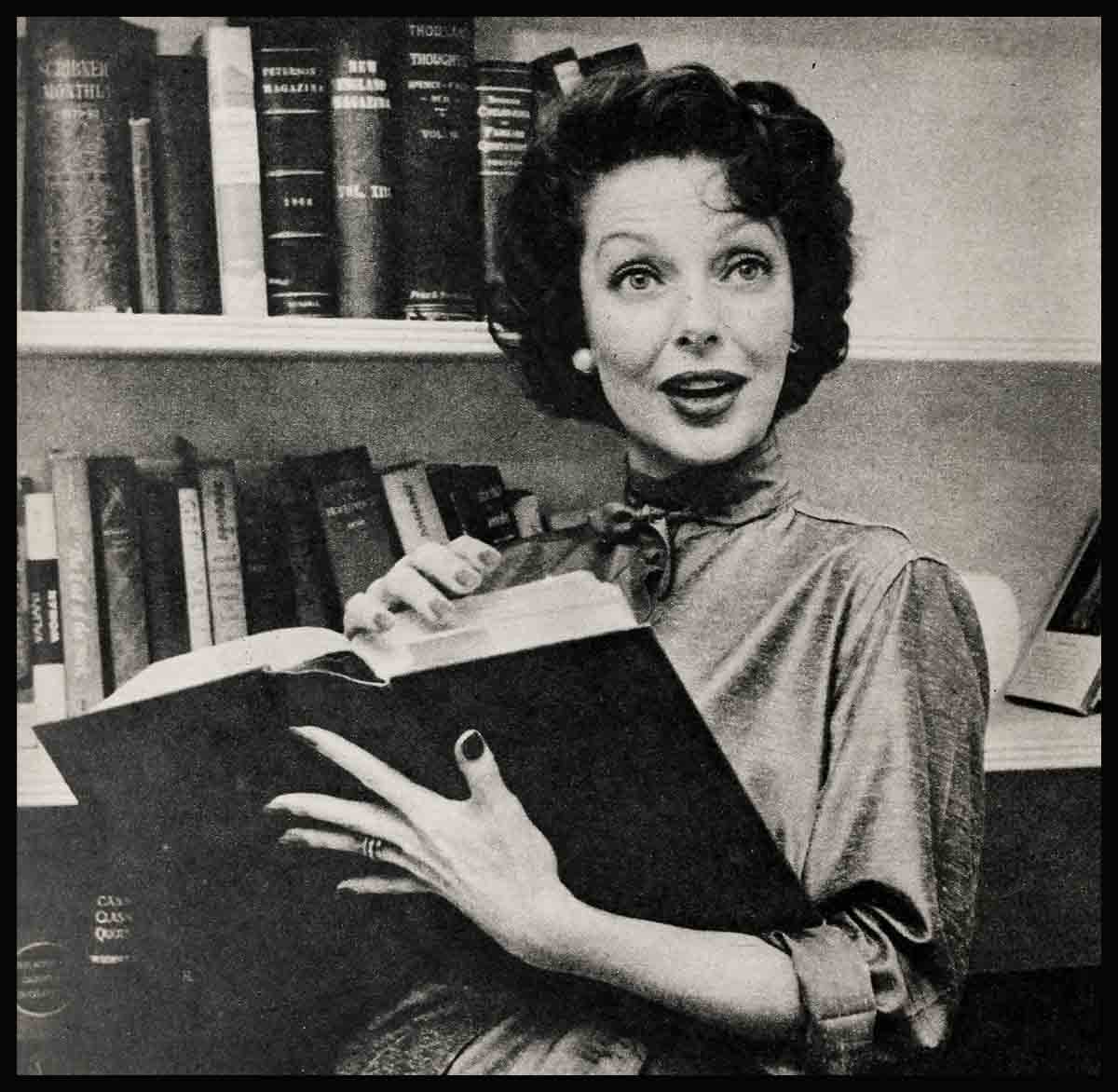

Shy Girl With Nerve

“You know how it is, I expect. There’s such a difference between what you are and what you are trying to be—nothing seems to happen for years, for eons . . . and then everything happens at once. You’re a little bit bewildered but you know it’s good.”

Eleanor Parker has just made this perennially astounding discovery. “Suddenly everything came into focus!” she says, wondering at the eternal marvel.

People on her home lot have been marveling, too. A year ago the girl who created a stir in “Between Two Worlds” and “The Very Thought Of You” was tagged as “difficult.” She was thorny and remote and no one in the big studio family felt that he really knew her. She seemed almost sulky in her ineptitude at human relationships. It was, of course, impossible for anyone on the teeming lot to realize that a girl who had made her way by sheer will power into pictures could still be agonizingly shy and unsure of herself. The will to be an actress and the shrinking violet attitude simply don’t go together, said Hollywood. It must be something else.

Then suddenly all kinds of things happened to Eleanor and she seemed to blossom, to come alive, to begin to be a person. She had,, to everyone’s amazement, got the role of Mildred in “Of Human Bondage.” She had been divorced. She had had her appendix out. And each one of these facts, she thinks now, contributed to her sudden breaking out of her sad, tight little cocoon. There was a subtle blending of physical well-being, emotional release and self expression.

But maybe we’d better go back to the beginning. She thinks the whole business dates from the time when she was a kid of about nine in Cleveland, Ohio, and confided to two of her playmates that she intended to be a movie actress when she grew up. They screamed with laughter and told other children about it and presently horrid little boys were chanting after her, “Oh, Ell-ee-nah! Of the cin-ee-mah!” filling her with rage but not altering her intention one whit. She was a naughty child at this period, she recalls, a hoyden and a tomboy, with a temper so violent that it worried her parents and sometimes actually made her physically ill.

She still has it but it no longer gets the better of her unless she has what she honestly considers “good cause.” She manages to justify her rages now and she hopes they are constructive!

When she reached the eighth grade she was a little exhibitionist. “I talked too much, giggled too much, asserted myself too much.” Then one day—she recalls it as if it were yesterday—she was in the school corridor, making quips “showing off,” she admits now, ruefully. An older boy who was the unwitting object of her youthful affections at the time, said quite loudly, “I detest silly girls!”

Eleanor wilted. She almost reeled. “He meant me,” she told herself. It did something to her. All through high school she hid herself inside a rigid little shell of reserve. She was miserable, unsure of herself, afraid of being hurt like that again. She was never gay, never indulged in any of the forms of self-expression which were giving her classmates fun and joy and growth. And her passion to be an actress grew and grew, although no one knew it for a long time except her wise and understanding mother.

“If you want it enough and work hard enough for it, it will come,” her mother used to tell her. And she arranged for Eleanor to have dancing lessons and voice lessons and all the other opportunities she might need for her heart’s desire. Later on, her father was equally sympathetic. He was head of the mathematics department of Cleveland’s Glenville High School and, although it must have put a strain on his budget, he was determined that his son and his two daughters should have whatever training and preparation they needed for the careers they planned, themselves.

So, when Eleanor was graduated from high school, she went on to study at Martha’s Vineyard. She earned part of her way there, working as a waitress. “All I can remember about being there was work . . . work . . . work.” But her father paid her expenses when she came on to study at the famous Pasadena Community Theatre. She planned to pay her father back with interest, someday. Then he could retire.

When she was nineteen (a little over three years ago) a talent scout tapped her in a performance at Pasadena. She was under contract to a major studio! Her dreams were beginning to come true. But there was still that strange, persistent fear and distrust of people . . . any people . . . no matter how much they tried to help her. “She won’t help us to help her!” her companions at the studio complained.

She bought a little house in the Valley and continued her lonely, withdrawn existence, working at her career, until one day, while she was playing in “Mission To Moscow,” someone brought an Army medical officer to visit the set. His name was Lieutenant Fred Losee and he was an aural surgeon, stationed at San Diego. They had lunch together and she concluded, “He’s the most conceited man I’ve ever met!” A little later they had dinner together and she gasped to herself, “I’m going to marry him! I know I am!”

And she did. They had two months together—as together as two people can be when one is in the Army and the other is a rising and busy Hollywood actress. Then he went overseas.

Warners wanted to remake “Of Human Bondage” and had discussed it with Edmund Goulding. Goulding was depressed. “Why even talk about it?” he demanded. “There’s only one actress in a generation who can do it . . . and it hasn’t been a generation since Bette Davis did it.” He decided he’d go back to New York and relax until the whole thing blew over. If the truth must be known, he wasn’t even enthusiastic about testing Eleanor. They sort of did it behind his back and then showed the test to him. He was electrified. “The girl has the greatest pure native talent since the young Garbo,” he pronounced.

Eleanor found herself playing Mildred in “Of Human Bondage.”

“I was never frightened or nervous about it for one moment,” she says now. “I knew it was right. I knew this was what I had been working for. Besides, Mr. Goulding knew it even harder than I did. He never said, ‘Do this . . . or that.’ He said, ‘We’ll do it together . . . like this . . . perhaps . . .’ This was the thing I had been waiting for since I was nine and the kids teased me. I felt nothing but serenity and satisfaction and . . . at long last . . . sureness.”

She continued to feel these nice things, even when her appendix began to misbehave while she was working in the picture. It began to be a touch-and-go matter, whether she could finish or not before they had to operate. Her husband came home on leave just then, too, and they decided, without dramatics, that their marriage had been an impulsive mistake and that they had best terminate it.

At the picture’s end she went to the hospital for her operation and she says now that she had time, while she was recuperating, to think things over, sort them out and clarify in her own mind “simply everything.”

Suddenly she was free . . free of the pain that had plagued her, free of constricting and puzzling emotional entanglements, free of the fear of failure and the fear of people. For the first time in her life she was completely sure of herself.

“I lay there in the hospital and sorted out my life, found my objectives . . . formed a sort of pattern. I felt wonderful!”

When she was well again and returned to the studio, people found it difficult to recognize this gay, cheerful, friendly girl who had once been sullen, irritable, almost impossible to know. Now she mingled, made friends, invited people to lunch, became the most co-operative of actresses about photographs, interviews, fittings. And she smiled constantly. She had lost her fear of life and of strangers, her fear of her own shortcomings.

“But even then I didn’t know exactly—concretely—what I wanted, except in my work. That took form one day in a soda fountain in Toluca Lake! From way back I had worshipped Janet Gaynor on the screen. Well, I was sitting at the soda fountain, drinking a coke one day when Janet came in with her little boy. I gasped. I longed to speak to her but I didn’t quite dare. But she smiled at me and I couldn’t have been more delighted if I had never seen an actress before.

“She looked so serene and lovely, just as I had known she would. But then I knew suddenly exactly what I wanted from life. I wanted to work, as she did, until I reached my peak. Then I wanted to do as she had done—retire, marry and have children. It seems to me she has reached perfection in her career and in her private life. I want perfection, too.

“A career isn’t enough for any woman, no matter how long she has wanted it and worked for it, or what she achieves. A home and family are necessities. I’m lonely when I go home to my little house. There is a great lack there. But it’s—well—a healthy sort of loneliness, I guess. It’s being lonely for the normal, natural things. And I know now that they will come.”

The “little house” is a smallish bungalow with a garden around it. After she acquired it, it was some time before she could consider it even partially furnished, she was so busy. She invited her entire family—father, mother, sister, brother and small niece—to visit her the first summer she owned the house, before she had even bought any rugs.

Now, she says, nothing in her house has any real relation to anything else. Her method has been to drop into a furniture store or an antique shop and decide, suddenly, “I like that. I’ll have it.” In that manner she has acquired chairs, tables, settees and an enormous four-poster bed. This has a wooden frame above it to accommodate a canopy and not long ago her housekeeper became so depressed at this bare structure towering above the sleeping Eleanor that she had it removed. Eleanor wailed, “I have to have the frame up there. Even if I haven’t a lovely, ruffled canopy—yet—I can lie here and imagine how it will look when I get it. Give me back my frame!” So back it went and there it still is, stark and undraped.

She frequently buys things because they are red—or white—or blue. Those colors stimulate her and she likes them in furniture and in clothes. A bright red chair or a blue sweater give her equal pleasure.

She subscribes to all manner of magazines about houses and she clips, somewhat haphazardly, everything she can find that has to do with a large, sprawling ranch house type of dwelling and pastes it in a book. She wants a “spread-out sort of home with big fireplaces and lots of ground around it and huge windows to look out on the trees and grass and sunlight”—someday. Then she will give her present house to her father and mother. She will give them a car, too And—her favorite dream!—she will buy her mother a really wonderful fur coat.

Just now she lives with the housekeeper, “who is rather like a mother,” and an old friend from Cleveland, a girl with whom she went to school, who is studying voice.

She likes to wear slacks (red, white or blue ones) and sweaters. She likes tailored suits and slim, plain evening frocks.

She has a fine collection of records, including almost every type of music. She thinks, with Lawrence Tibbett, that there is no “bad kind” of music.

After she came out of her shell and began to feel, as she puts it, “alive and real,” she discovered a hobby. She bought herself a drawing board and began to sketch. She has had no instruction. She doesn’t know whether what she draws is good or bad. But she loves doing it. It lifts her out of herself and relaxes her.

She finds herself being actually grateful for things which might have caused her acute woe a few years ago. For instance, she worried for a long time over the fact that she had strained her voice, weakened it so that occasionally it fails her completely. Now she realizes that that voice strain gave her the “throaty” quality which is so valuable to her now.

She is grateful for the fact that for the first time since she can remember, she actually, definitely enjoys eating. “Before my operation, it was so difficult for me to force myself to take food that I knew I had to have,” she says. “I can’t tell you what an interesting experience it is to be really hungry, to look forward to a meal. Certainly that’s a simple, fundamental pleasure for most people. You can’t know what an important pleasure it is unless you’ve been deprived of it!”

There are other things—niceties of living, exciting experiences with clothes, food, parties, people, entertainment—that she thinks she will learn to enjoy in a discriminating manner, when she has time, when she can cease to concentrate so completely on the actual business at hand. She looks forward to these things, looks forward to enlarging her capacity for enjoyment. Most of all, she looks forward to being friends with lots of people.

Oh, yes! One of her very first fan letters was from that smug “older boy,” the one who called her a “silly girl.” He took it all back. “But,” Eleanor admits now, “d’you know, I’m still a little bit afraid of him!”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945

No Comments