Duke-Prince Among Men—John Wayne

The first time I spoke to John Wayne, I didn’t know whom I was talking to—and didn’t care. It was 5:30 A.M. when the telephone rang and some very funny comedian asked if I wanted to go to Mexico City for a week.

“Oh, sure,” I said and hung up.

Six hours later I discovered that. the “very funny comedian” had been John Wayne. That was when Duke knocked at the door and asked why in blazes I wasn’t ready. I said something about a missing sock, closed the bedroom door, emptied half a dresser drawer into a suitcase and was on my way to Mexico.

Wayne, director Budd Boetticher and two men from the location crew were on their way to scout locations for “The Bullfighter and the Lady.” This was Duke’s first production. He wasn’t going to play in it himself so I spent the ride thinking up several dozen good reasons why I should get the part of the Brooklyn boy turned bullfighter.

No one even mentioned the picture. Duke admired the scenery; Budd gave us a history of Mexico and the rest of the group played gin rummy in the back seat. The closest Duke came to talking about the picture was to say that we were going south “to get the feel of Mexico.”

We got the feel of Mexico all right. Or perhaps Mexico got the feel of us. Mexico drew me like a magnet. I was magnetized by the dry red earth, the white plaster buildings glittering in the sun, the intense faces of the people in the streets.

I got the impression that Duke felt the same way. The last morning, I knew that he did. We were standing outside the training ring at a bull ranch, watching the becerras, those dangerous little cows who were being tested to determine whether they had the courage and the strength to become the mothers of fighting bulls. If so, their sons would, perhaps some day in the future, fight and die at La Plaza de Toros in Mexico City.

“Fine country, Mexico,” Duke “Damn fine country.”

I think he was searching for a word to describe how he felt. There is such a word. He didn’t know it then, nor did I. It’s a word that has no equivalent in It’s a word that describes the way halite feel about bulls and perhaps the way that bulls feel about bullfighters.

Simpatico.

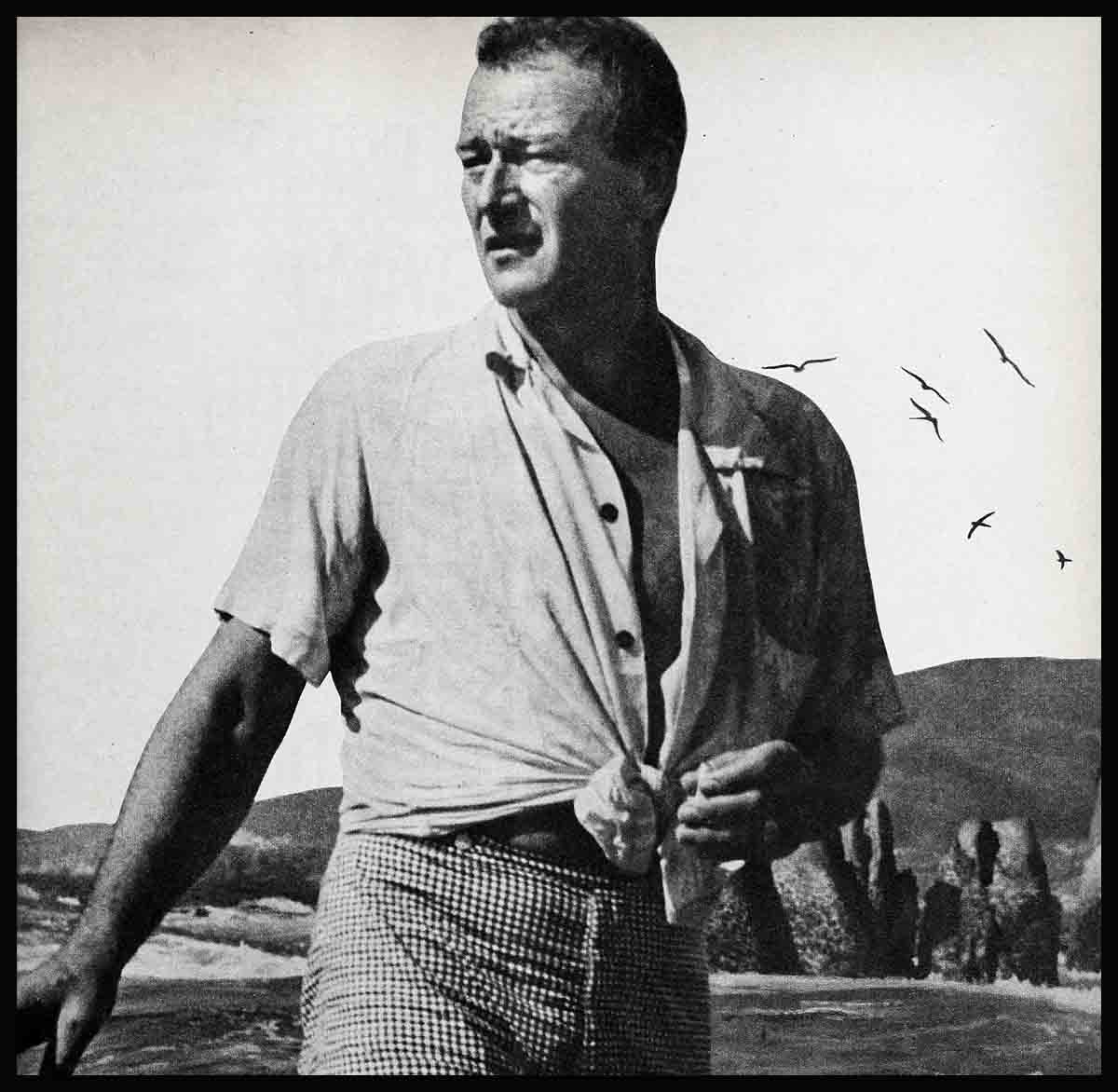

The word is part of Duke’s vocabulary now—and mine. But on that morning he didn’t know that Mexico was to be simpatico to him or he to it. He just stared at the other bull ring, standing in the hot sun, watching the novice bull knock over the apprentice toreros.

Without moving, without turning his head toward me, he said, “Want to try it, Bob?”

I looked into the ring. Baby bulls who weighed nearly half a ton. Bulls whose horns weren’t big enough to slash with but who pounded their opponents against the walls of the ring.

“Okay,” I said.

Then I stood in the ring, squinting against the sun. One of the men tossed me his cape.

I held the cape awkwardly in front of me. I waved it at the bull, and he charged. I jumped aside and turned to face him again. This time his horns caught my arm and spun me around. Next time he did even better; he hit me square in the stomach. Knocked off my feet, I rolled over on the ground. I got up, brushed myself off and tried again.

I was a novice, all right. When I finally limped out of the ring, my arm bleeding from a stone cut, I was still carrying the cape. Duke took it from me, tossed it over his arm and walked slowly down the steps into the ring.

That is something that is integral to Duke’s sense of honor—his refusal to ask anyone to do something he is not willing to do himself. Of course, he is such a superb natural athlete that this is something like a jet pilot’s inviting you to take his plane up and try a few fancy rolls. Duke has the walk of a panther and the coordination of a cat and that day, when he had never been in a bull ring before, the bull only brushed him twice.

That was our last morning in Mexico. The picture had not been mentioned all week. I didn’t really know whether I was being considered for it. I hadn’t been asked to test for the part or to read for it, the usual ways an actor gets a role in Hollywood. I found out the next morning when the assistant producer called.

“Hey,” he said, “did you fight a bull yesterday?”

“Sort of.”

“All I know is, Duke says you got guts. The part needs a guy with guts. So, get on over here. You’ve got the part.”

I got on over, thinking as I drove that no other man in Hollywood would give one of the best parts of the year to a man he had never tested on film but who seemed to have passed some sort of private test.

Duke was waiting for me. “You lucky stiff,” he said, looking down at me. I’m over six feet tall, but I’m still a good three inches shorter than Duke and a good thirty pounds lighter.

“You lucky stiff,” he said again. “I’d play this part myself if they’d let me. But I can’t fit into those blasted bullfighter pants.”

From the moment we started the picture, Mexico and John Wayne were simpatico. Mexico is a strange country, simple on the surface. But violence and passion lie beneath that surface. Its borders dip against the tropics, and strange things mushroom from the earth in those places. The land is like that, and so are the people, and both accepted Duke as a friend immediately.

Most of the people we met were connected with the bulls in some way. They were bullhandlers or bullranchers or owners of the stadiums where bulls fight or los toreros—the bullfighters. The bull-fighters. They are more important than presidents, than kings, than movie stars.

They are not just a little more important. There is simply no comparison between a bullfighter and anyone else. For example, a friend of mine was being driven around Mexico City by a wealthy Mexican who was proudly demonstrating his new Cadillac. Suddenly a dented car swept around the corner on the wrong side of the street and crushed the Cadillac’s fender. The Mexican rushed to the other car, shouting insults. Then his shouts stopped. In the other car was Silverio Perez, one of Mexico’s most famous and revered bull-fighters.

“Silverio,” the Mexican said, shaking his hand over and over, “mi compradote, what an honor to meet you, what an honor.”

Bullfighters, like kings, choose their friends. And the first time Silverio and Duke met, Duke was chosen. It didn’t matter that Duke spoke only six words of Spanish and Silverio a few sentences of English. They were simpatico.

One evening Silverio threw a big party at one of the bullfighters’ clubs in Mexico City. It’s a tremendous restaurant, on the walls are bull heads and ears and tails, mementos of famous fights. Duke and I were the only Americans there.

We were led to a private dining room on the second floor. In front of each place was a bottle of tequila and a glass. Duke and I looked at each other, wondering if we were expected to drink the whole bottle. I had tried tequila once before and I knew it had something of the effect of raw alcohol and gasoline lit with a match. Duke dead-panned me and I knew we’d drink as our hosts drank, even if it meant we’d never be able to swallow again.

Silverio motioned for silence, and we were introduced to the ritual of the bells. In this ritual, each man faces the man next to him, links arms and then when the silver bells are rung, drains his glass. Luckily, this ritual didn’t last very long. Then the speeches began.

When it was Silverio’s turn, he stood up. “Only two gringos do I love,” he said. “You Robertito,” and he put his hand on my shoulder. “And you, Duke.”

Duke was standing, too, looking down at Silverio who is a small, slender man only half his size.

“You, Duke,” he said again and gave Duke a firm abrazo—the embrace that to the bullfighter is like the ceremonial kiss a French general bestows on a man he is decorating for valor.

Duke just stood for a minute, so moved that he couldn’t answer. Then he unbuckled his gold and hammered silver belt and handed it to Silverio. Silverio put the belt on, wrapping it twice around his waist before it would fit.

This gesture probably cost Duke five or ten fans. They were waiting for him in the hotel lobby. He passed them by without stopping, and I found it impossible to tell them that he couldn’t sign autographs because he was holding up his pants with one hand.

Bullfighting is an art, not a sport, and the men who face death in the afternoon and those who watch it have an acceptance of the facts of life and death. With this acceptance goes a capacity and an ability to live each moment furiously—to get drunker than anyone else when they get drunk and to be soberer than anyone else when they are sober. These men took to Duke, I think, because his code was so close to theirs, so close to the basic, elemental truth—a man should live each moment as well as he can and never cringe before any.

Nothing ever angered him except incompetence or pettiness. Faced with anything else, he grinned and accepted what had been dealt.

Duke seemed always to do the right thing without thinking about it, and this is difficult in a country that does not always accept Americans with open arms. Once, we were having lunch at a bull-ranch where we had just started to shoot. Our food was brought in from Mexico City, and our crew had taken over the big ranch dining room. We had just begun to eat when we saw a group of thirty or forty children looking through the windows and doors. They were dirty, thin and obviously had never quite had enough to eat.

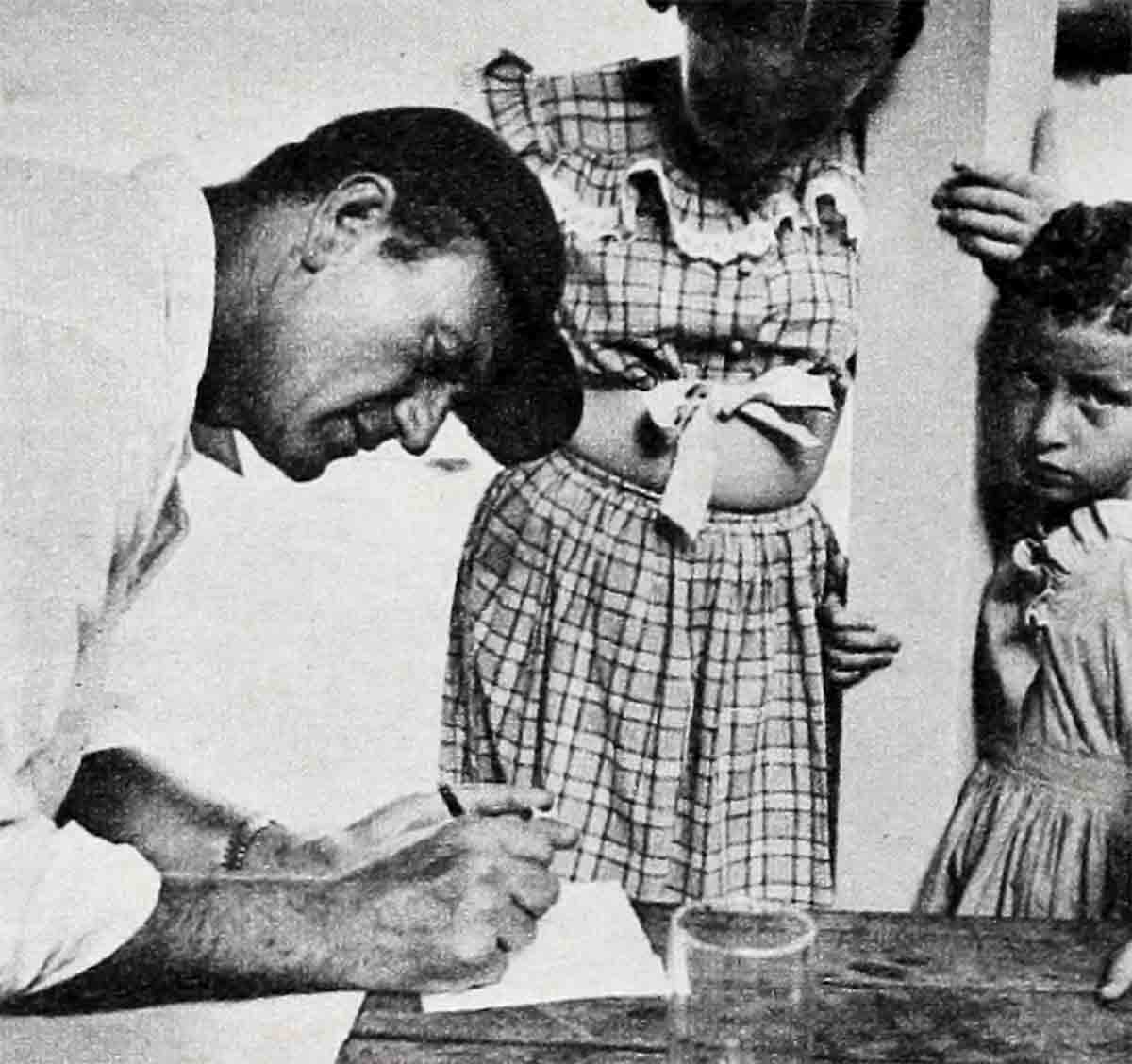

Duke saw them, picked up his hat, scoped about fifty or sixty sandwiches into it and took them out to the children.

A few minutes later one little boy returned with his hat. “Thank you for the cake,” he said very slowly in English.

Duke bowed. “De nada,” he said. “You’re very welcome.”

That was not a gesture. It was John Wayne.

It was not only the bullfighters who liked Duke. I noticed that a young Mexican named Carlos always handled Duke’s transportation, the shipping of cast and crew to the ranches and towns around Mexico City. And the car Duke rode in was John was always driven by Carlos. I asked Carlos about it one day.

“That Señor Duke, he said. “He is a man.”

Then Carlos told me the whole story.

“He set me up in business,” Carlos said. “The first time he comes to Mexico City, I have only one cab. He wants me to take him to a place someone has told him about. I say, ‘No, that is too rough a place. That is where the bandidos—the bad men—go.’ But he wants to see it. He wants to see everything here. And so we go.

“At the next table a man throws his cigarette on the floor and points to Señor Duke. Luckily Señor Duke does not understand what he says because he speaks in Spanish. ‘Vamonos,’ I say to Señor Duke. ‘Let’s go.’

“The man says something worse, and Señor Duke just stands there, big against the room. ‘Tell me, Carlos,’ he says. And so I tell him. I can do nothing else.

“Then Señor Duke hits the man and knocks him half across the room and stands there, waiting for the man to get up. The man gets up, but when he comes back, he has a gun in his hand. It is too quick to do anything. He pulls the trigger. And the gun does not go off. There is no cartridge under the barrel. I think I hear Señor Duke’s heart stop beating for that moment, but he has not turned pale, he has not cried out. Then I knock the man’s arm aside before he can shoot again, and Señor Duke hits him again. This time he stays on the floor.

“Then I drive Señor Duke home. The next day he sets me up in business. That Señor Duke, he is a man.”

Four years have passed since that picture and that night in Mexico and, like all of us, Duke has changed. Today I do not think that he would, without thinking, pit his strength against a bull or face an angry man with a loaded gun. Not because he has learned to be afraid. He is the only man I have ever met who is not afraid of anything.

But he has accepted the discipline of responsibility. Today he is aware that a million-dollar investment would walk into the bull ring with him. Six years of producing pictures have made him aware of that and of the multiple obligations that he has.

On the set of “The High and the Mighty,” my second picture for Duke, there were none of the violent arguments, none of the raucous gags. Duke was quiet and serious. More often than not he gave instructions, criticisms or suggestions in a low, quiet voice. He seemed subdued, perhaps a little older. More mature but no less a man.

His sense of fairness, his generosity, his loyalty were still with him. I know that they always will be.

He was the star of “The High and the Mighty,” and he was its co-producer. If he had wanted his name in letters eight feet high on the screen, his name would have been in letters eight feet high. Instead he specified that his name was to appear in all advertising the same size as all the other stars’ names, because it was a team picture. And Duke knows all about team play.

An unwritten law says that a big star will appear eighty per cent of the time in any scene he plays with a younger actor. This is ensured by taking close-ups of the star after the scene is shot. When I had finished my big scene with Duke, he said he thought it was swell.

“Okay,” Director William Wellman said. “Let’s shoot those cover shots now.”

“No,” Duke said. “I think the scene went okay.”

“But we have to . . .” Wellman began.

“I’m tired,” Duke said and walked off the set. “Go on to something else.”

Those close-ups were never shot. Duke wasn’t tired. It was his way of telling me that he had liked the scene and that he wanted me to have an equal chance in it on the screen.

Duke’s loyalty to his friends is legendary. On “High and Mighty” one morning someone came in with the news that Duke’s make-up man, Webb Overlander, had broken three ribs in an automobile accident and was now in the hospital.

Duke finished the scene. Then he picked up his hat, turned to Wellman and said, “Shoot around me. I’m going to see how Junior is.” He didn’t come back for two days until Webb was out of danger.

The only time he got angry at me, Pilar Palette had come unexpectedly onto the set and was motioning toward Duke. I was trying to get him to let me change a couple of lines in a scene, but his mind kept wandering toward the corner of the stage where she waited.

“Please, Duke, listen,” I said, and he blew up.

Then he grinned. “Sorry, Bob,” he said. “Just wait a minute, will you?”

I watched him walk over to her. She said something and he smiled. Then he reached for her hand, held it and stood there a minute without saying anything. When he came back, all the pent-up tenseness was gone.

“Quite a girl,” he said. “Simpatico.” Then, “Okay, what the heck are you standing around for? Let’s get back to work.”

“Come on,” I said, “the cast-iron duke wants us to work.”

“Sure,” he said. “I’m the original iron man. I eat actors for breakfast every morning.” He grinned. “I’m tough,” he said.

I finished the scene and the next time I looked up, the original iron man was serenely holding hands with his wife in the doubtful privacy of an unlit spotlight. There was an expression of peace on his iron face.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1955