The Tommy Sands & Nancy Sinatra Story

From the window of her room, Nancy could see the flagstone path that led up to the house. It seemed a million years ago that she had kissed Tommy goodbye on that path and yet, when she wasn’t missing him so terribly, she knew it had only been a month ago that he had left for basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. She turned to look again at the little clock on her bureau. What was keeping the mailman? And then, turning back to the window, she spotted him as he turned the corner onto her street. She thought she had never seen a man walk so slowly. Finally, though, he was at her house. He paused, but then she saw it was only to adjust the heavy sack on his shoulders. She watched, disbelievingly, as he continued down the street. Her eyes were clouded as she turned away from the window. No letter from Tommy again. She tried to tell herself that he was busy, that basic training left him little time to write, that, anyway, they’d agreed they wouldn’t write each other.

AUDIO BOOK

“I’ve never been one to write letters,” he’d said. “I’d rather phone.”

And she’d agreed. She was like that, too.

“Besides, a letter would take two days to get to you,” he added. “And I couldn’t wait that long for an answer.”

“Me neither,” she said. “I’d think of a dozen other things I wanted to say to you by then.”

So she knew she shouldn’t wait for the mailman. And yet . . . A letter would be so nice. She could keep his letters in a drawer, tied together in a ribbon, and when she was feeling lonely, she could take them out and read them over and over. Whenever she was troubled by doubts, whenever she thought how far apart they were, she could take out his letters and read and reread the parts where he said, “I love you. . . .”

It was a couple of days now that she hadn’t heard from him, and she couldn’t help worrying. He was just learning to fly. Maybe . . . maybe there’d been an accident. A shiver ran through her. And there was another worry, almost as awful, that nagged at her. What if, being apart, he’d thought things over? What if he’d changed his mind about her?

She shook her head, as if to chase the thought away. She tried to tell herself that, when they’d been apart before, it had only made them love each other more.

It was at the end of February, when her dad had asked her to fly to New York, to be his representative to welcome home Elvis, who was going to be on TV with Dad and her. Meeting Elvis had been exciting and yet, with Tommy so far away, she’d felt lonely and miserable. They’d call each other but it was awkward and strange. It was so difficult to talk from three thousand miles away.

And then one night at about 2 a.m., the phone rang in her hotel room. It was Tommy. “Nanny,” she heard him say, “I love you.” Then quickly, before she could answer, he added, “You don’t have to give me your answer right now, but I love you and I want to marry you and I want us to become engaged right now.”

“Yes,” she said, answering right away, in spite of what Tommy said. “Yes.”

They talked for about forty-five minutes.

“I’ll have a ring waiting for you when you get home,” he said.

“No, don’t spend the money,” she answered. “I don’t need a ring. You can buy me one later, I don’t care. Let’s save our money for furniture and things we’ll need. Please, don’t worry about getting me a ring.”

But he hadn’t listened. The next day, Tommy was at her mother’s house asking her what kind of ring Nanny would like, and then going off with his own mother to pick it out. He’d gone from one appraiser to another, trying to make sure that the ring he’d bought for her was just perfect.

“Just be sure”

And it was perfect. It was the kind of ring every girl dreamed of. A four-and-a-half carat diamond, emerald cut, with two baguettes in a platinum setting.

She looked at it now as it gleamed on her finger, as she waited, hoping that today Tommy would call. It was so hard to be apart. With the miles, seem to come misunderstandings. They were only little things and she knew deep inside that if Tommy could reach out and take her hand, everything would be all right. But he couldn’t . . . and the doubts wouldn’t go away.

She remembered her father’s words. “You’re old enough to make up your own mind. Just be sure, that’s all.”

Just be sure. When she’d flown back, finally, to California and they had told people how the engagement had happened, she had been sure. She’d worn a white silk, long-sleeved blouse and a slim black skirt with black opera pumps and Tommy had had on an all-black sports outfit. She always like the way he dressed.

They’d met the reporters in the wood- paneled den of her house, with her mother there, too. Someone had asked, “How can you be sure you’re going to stay in love?”

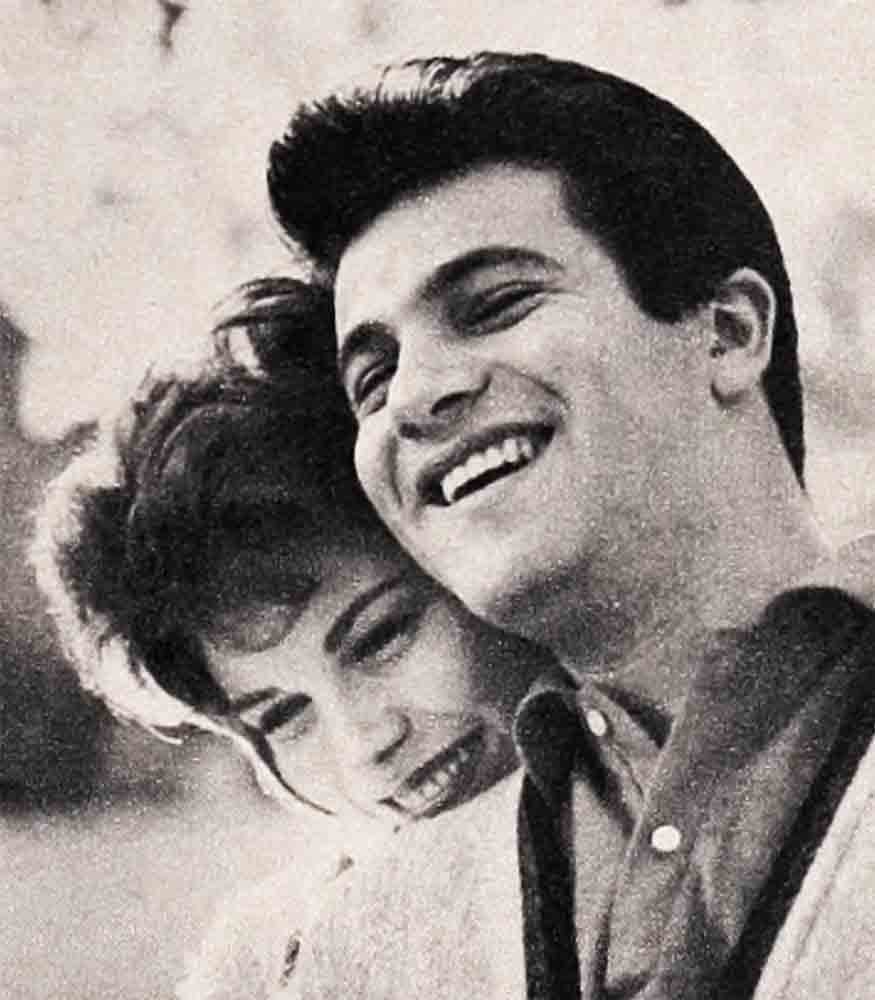

“From the very first,” she told them, “I saw a sincerity about Tommy. I saw someone who was on the level, who never said anything unless he meant it. I saw a wonderful, exciting and yet nice boy and I knew how refreshing and rare it was to find someone in this town and this business who was like this. From the first time we started seeing each other, he was so considerate, so understanding.”

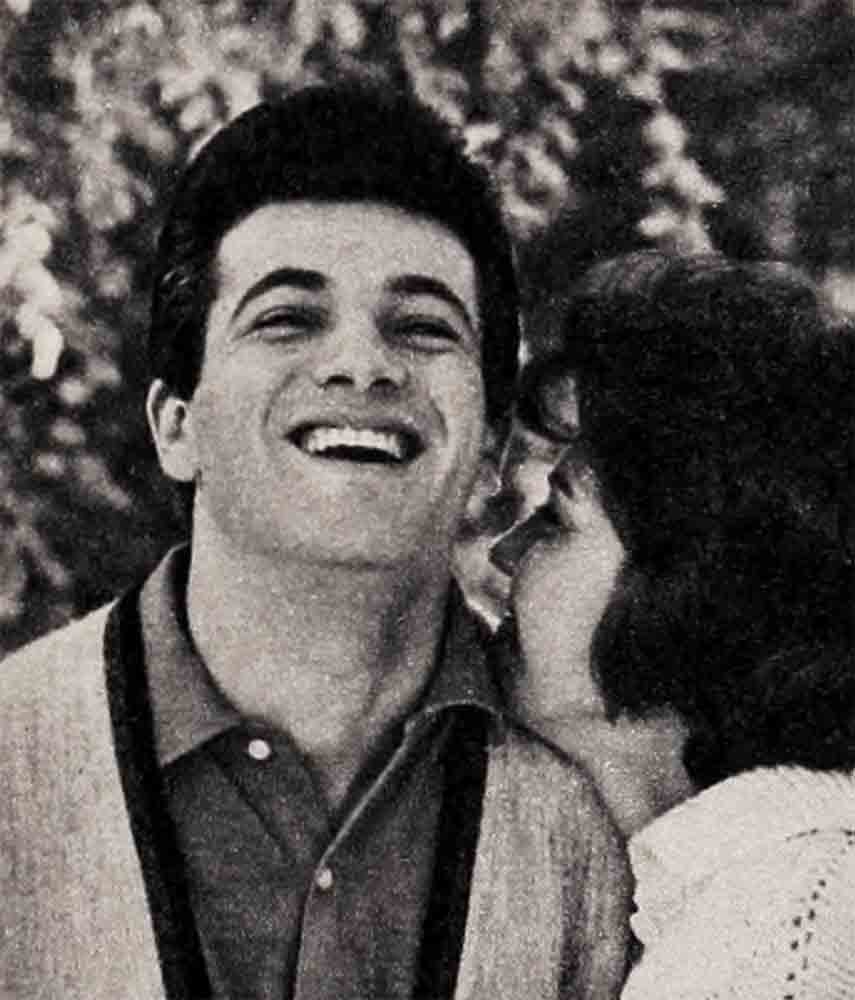

She remembered how, after they got engaged, they had tried not to be separated again. They both knew he’d be going into the service and till then they wanted to spend every minute they could together. Her mother had understood. She’d agreed to go along as chaperone so Nancy could be with Tommy when he went to sing at the Eden Roc in Miami Beach. She’d sat at a ringside table every night, aglow with pride at the way Tommy could make an absolute hush come over the room. People listened so intently while he sang and, afterward, they clapped wildly for him, making him sing encore after encore. “I thought they’d never let you off the stage,” she had told him, laughing.

Then came the vacation she’d been looking forward to. Mother, Tina, Frank Jr. and herself were all supposed to go to Hawaii. They’d been planning it for a long time. But at the last minute, she couldn’t go.

“I can’t leave Tommy,” she begged her mother. “We have so little time before he goes into service.” And finally her mother had agreed that she could stay home.

“Maybe we’ll go to Hawaii on our honeymoon,” Tommy had said. He was always making plans. She remembered the first big one he’d made.

It was just before Christmas and Tommy had said, “Let’s go where the snow is.” They drove up to Lake Arrowhead and the Big Bear mountain and spent the whole day there. They had dinner at the ski lodge and then they started to drive back. It had been a perfect day.

On the way home, Tommy had been exceptionally quiet. She’d never seen him look so serious. Finally, he said, “Nancy, I’m going to mention something now, and then I’m not going to bring it up again for a few months. But if we both feel the same way in a few months, I’m going to ask you to marry me.”

That was Tommy’s plan. She’d just listened, without saying a word. She hadn’t known it was coming, though now she thought that, deep down, she might have wanted it to happen. But then they’d only been dating a few weeks and it scared her. She didn’t want to think about it, in case things didn’t work out. She didn’t want either of them to be hurt.

Suddenly the phone in her room rang, startling her back to the present. For a moment she hesitated, afraid to answer it, afraid to find that it wasn’t Tommy. Then slowly she picked up the receiver.

But it wasn’t Tommy after all. It was | one of their friends, asking her to come to a party . . . the whole gang would be there. For a moment, she wanted to say yes, she’d come. But then she remembered.

“No,” she answered slowly. “I . . . can’t.”

You can’t just sit home every night, Nancy,” her friend told her. “Why don’t you come? It’ll do you good.”

“No,” she repeated, “I can’t.” She was grateful for the way the gang kept asking her to join them, trying to keep her from being too lonely.

Finally, she said, “Well, maybe ‘ maybe I’ll come by later.” But she knew she wouldn’t. A party wouldn’t be any fun without Tommy. Everyone else would be paired off and she would only feel more lonely.

The times he didn’t call

She put the phone back on its cradle. It wasn’t even noon yet, but she had to stay home, at least until eight o’clock. Then, she knew, it would be nine o’clock where Tommy was. She always waited at least that long. If he hadn’t called by then, she knew she wasn’t going to hear from him that night. After that time, it was no longer possible for him to get to a phone; it was “lights-out” in his barracks.

She tried to understand, the times he didn’t call. She would tell herself it was because somehow, all day, he hadn’t been able to get near a phone. And yet . . . She needed so to hear his voice. She looked at the phone. It was like a lifeline to her. And there was so much she had to tell him.

On the days Tommy called, she’d be floating on clouds. And yet there were also times when his voice sounded so strange, so different. She would try to tell herself it was just the long-distance wire but sometimes, after they’d hung up, she would ache to pick up the phone and call him back, to ask him, “Please, Tommy, is anything wrong? Please . . . tell me.”

She couldn’t help wishing they were married already. They had talked about eloping. “August,” they’d whispered. But she knew she couldn’t do that. The Church would be against it and it would hurt her family, too. No, they had to wait.

“It isn’t as if we had to run away and get married because we don’t have our parents’ approval. Everyone approves,” Tommy had said, trying to be practical. “We know we’re going to be married and we have the security of our love for each other and so we can wait.”

She’d nodded. “Besides,” Tommy said, “if we got married now, you’d be living in a motel or something near Long Beach or wherever it is I’ll be stationed after basic. I don’t want that for you. I want us to have a real honeymoon.”

She’d had to agree. “Too many young people get married and make a drudge of it,” she admitted. “When we’re married I want us to be together constantly. I’ll even travel with you when you go on tours. And we’ll really get to know each other and enjoy each other and then,” her voice became low and shy, “we’ll settle down and raise children.”

They agreed to wait.

And besides, the big wedding they were planning would be so romantic.

“You’re romantic,” Tommy had laughed at her.

“I guess I am,” she admitted. It was just before he went away that she told him, “You know, I’ve already decided that I’ll never go around our house with my hair in curlers or wearing pants and all that. I’ll never let you see me like that. I always want to look my best for you.”

He kissed her on the tip of her nose. “And I want us to have music playing during dinner,” she whispered, “and candles burning on the table. Little touches like that are important in a marriage.”

“Okay,” Tommy had grinned. “You promise to love, honor and play my records during dinner.”

She’d laughed and rumpled his hair. “And you promise not to notice if the food is burned. If we eat by candlelight, you won’t be able to see anyway.”

She smiled at the memory of it. And she remembered, too, how she’d teased Tommy about his six-months in the Air Force. “You’re just going out of town to get out of the work of the wedding,” she’d laughed. She sat down at the desk where she’d already begun to plan the guest list, but when she counted up the people she was planning to ask, she couldn’t believe it. Four hundred names! And that was without the people Dad would want to have; she figured they would come to about another two hundred. She shook her head ruefully. She didn’t want that big a wedding. Before she’d started to make the list, she’d thought there’d be about three hundred. But it seemed that every day they’d remember someone else who just had to be invited. If she didn’t ask them, she knew they’d be hurt. It was funny how something as wonderful and happy as a wedding could somehow end up with hurt feelings. She didn’t want that.

The same initials

If only her father were back in California. She wanted to talk to him about the wedding, to get his advice on her plans. It was months away but there was so much to plan. The flowers and the music and the food. The bridesmaids. Her dress. She wanted everything to be just perfect.

Dad would be home soon. She wanted to ask him, too, about what to do about her career. She didn’t want to do anything without his advice, but, ever since she’d been on TV with him and Elvis, so many people had been calling her up, asking her to be on this TV show or sign that contract.

“. . . and they even want me to be in a movie,” she’d told Tommy excitedly when he’d called her last week.

“That’s great,” he’d said, and his voice had sounded full of enthusiasm. But suddenly she remembered the long talks they’d had. Two careers in a family could hurt a marriage, they’d agreed. Was he remembering that, too?

“Whatever I do,” she said, “I would never let it keep us apart. When you get back, I don’t want us ever to be separated again.

“Nothing could ever interfere with our marriage,” she insisted, when he didn’t answer right away. “You’ll always come first with me.”

“I want you to have a career if it’s what you want,” he told her. “I’d never want to hold you back . . . I’d be proud of you.”

But it had been so hard to talk on the phone. Was he really happy about it? If only she could see his face . . .

She told him that, if she did have a career, she thought she’d keep the name of Sinatra.

“But the initials will still be the same,” she added quickly.

“Hey, is that why you’re marrying me?” he teased. It was his way of telling her everything was all right. “So you won’t have to change any of your monograms?”

She was happy when she’d hung up the phone that night. This time there were no doubts about what he’d said, no worry that he hadn’t understood what she said. If only it could always be like that. . . .

Yet, in her heart, she knew that Tommy always understood. Only it was hard not to wonder . . . She had seen the pictures taken of him just after he went into the Air Force, when his hair had been cut short. Being in service was a whole new way of life for a man, a tremendous experience that couldn’t help but change him. What other changes would she find the next time she saw Tommy?

In the quiet of her room she remembered ack to the last time she had seen Tommy.

The going away party

She had wanted that to be so perfect. She was going to give him a big going-away party at her house. Tommy got such a kick out of parties and she planned for days to make this one that they could both look back on while they were apart.

She was on the phone constantly, inviting all his friends. “Hey,” he’d complained, “I can’t even call you up these days. You’re line’s always busy.” They planned to clear out the furniture in one of the rooms downstairs so there’d be lots of room for dancing and they’d put decorations all over the place. And she worried about the food. In the middle of the night, she woke up and had to call Tommy. “You’re sure you’re not just saying you like Italian food?” she asked.

The worst problem was what to wear. She’d stood frowning in concentration be- fore her closet, trying to pick out a dress. There was one that Tommy especially liked. “It does something to your eyes,” he’d told her. Still, maybe she should buy a new dress. . . .

And then, just when everything was all set, Tommy called. She answered on the downstairs extension and she knew some- thing was wrong the minute she heard his voice.

“Nanny,” he said, “I’ve got awful news. I just heard from the Air Force. They want me to report a few days earlier . . . on Saturday.”

“Oh, no, Tommy,” she moaned.

“I feel awful . . . I guess it messes up the party . . .”

“The party!” she’d gasped. For a moment, she’d forgotten all about it. But now, as they talked, she heard a loud pop, as one of the balloons her kid sister Tina was helping blow up, burst.

“Well,” she told him, “we’ll just have it earlier.”

They moved the party up a couple of days, but just when she’d finished calling the last guest up and telling them about it, Tommy heard from the Air Force again. They’d moved his induction up once more. There was no time for a party.

They’d both felt cheated, and it wasn’t only because of the party. It was as though those last precious days, together, had been stolen from them. They could never have them back again.

She hadn’t even been able to go to the airport with him. Tommy’d had to drive out in the Air Force bus while she had gone out with Eddie Goldstone, the boy who’d first introduced them. She’d cried all the way.

It wasn’t fair.

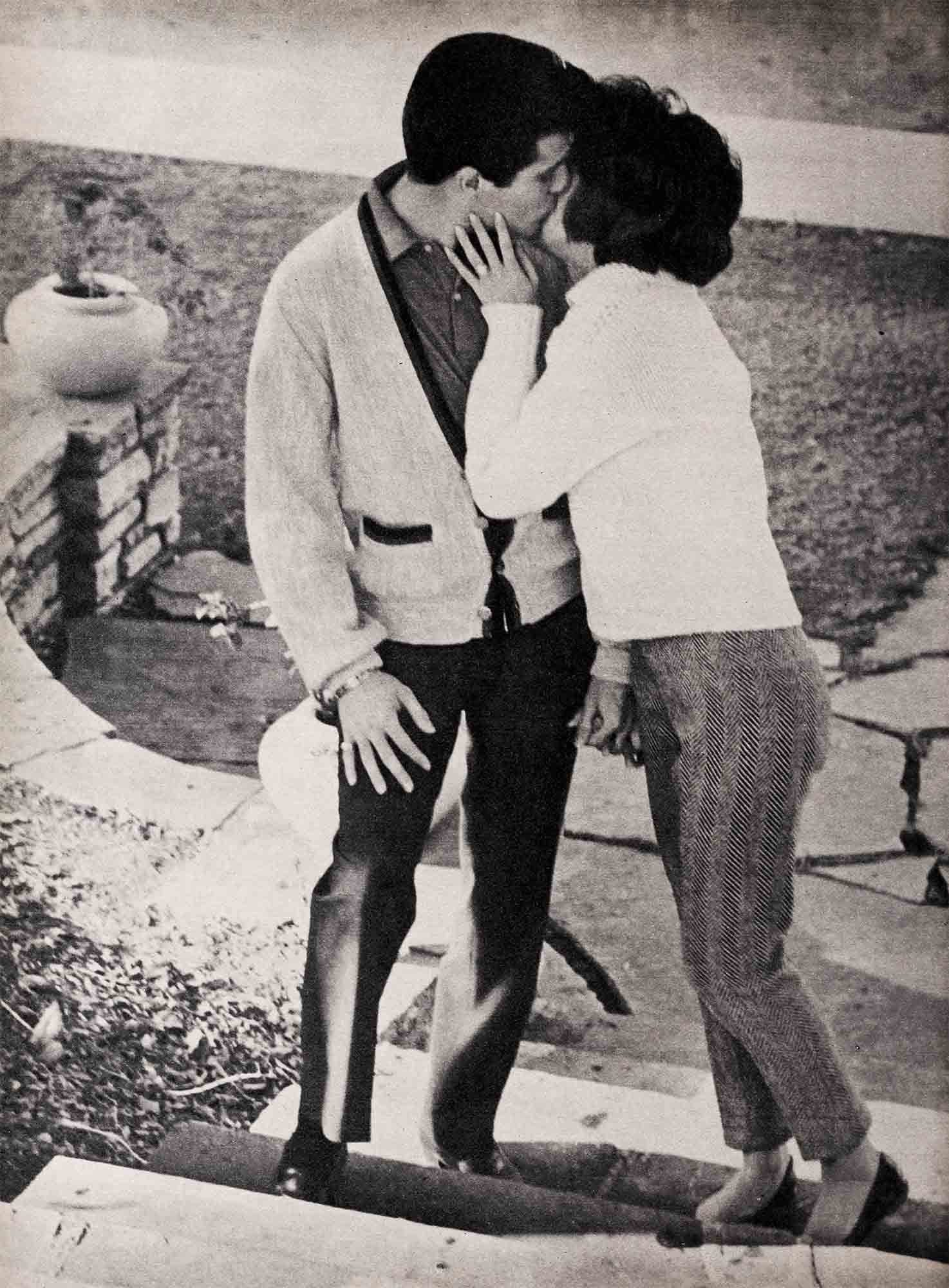

Suddenly, when she should have had a time, she was kissing Tommy goodbye.

Suddenly, when there were still so many things to say, there was only the unspoken plea, “Love me, Tommy, even when you’re far away . . .”

Suddenly, when he should have still been with her, Tommy was gone.

She looked once again at the clock on her bureau. Ten minutes to twelve. The hands didn’t seem to be moving at all. Yet she knew the clock hadn’t stopped. She could hear the ticking.

“I love you, too”

And then, suddenly, the silence was broken. The phone rang and this time she leaped to answer it.

“Yes . . . yes,” she told the operator, “this is Nancy Sinatra speaking.”

And then, there was Tommy’s voice. She thought he sounded tired. Was he ill?

“Tommy,” she said, trying to keep her voice calm, “are you all right?”

“A little bushed,” he said. “We just got back from a bivouac. It was murder . . . not a phone for twenty miles.”

“Oh, I was so worried,” she said breathing a sigh of relief.

“I knew you’d be,” he said. “I thought I’d never get to a phone. There was such a line of guys waiting to call . . . Nanny,” he said, “I miss you so. At night, I started to write, but I couldn’t seem to get down what I really wanted to say. The words just didn’t look right and I tore the letter up. Nanny, how are you?”

“I’m fine, Tommy. I’m fine—now,” she whispered.

“Me, too,” he said, “I love you, Nanny.”

THE END

HEAR TOMMY SANDS SING ON CAPITOL LABEL

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1960

AUDIO BOOK