Dream Girl—Shirley Temple

I’ve been doing stories on Shirley Temple for twelve years.

I remember her at 7, feeding the bunnies behind her studio bungalow before you could get her to eat her own lunch.

I remember. the mirthful look in her eye at 9, when somebody asked about her ambitions. “That depends,” said Shirley. “Right now I’m making a paper basket, and most of anything in the world I want some paste.”

I remember the schoolgirl of 12, sweater sleeves pushed back, the fifty-five famous curls forever vanished. “Thank goodness,” their owner remarked.

I remember her at 16, young enough to be driving the family nuts with some strange brand of doubletalk, old enough to be wearing a forget-me-not ring whose giver was a secret.

I remember the way she looked a few days ago on the lawn of her house, flanked by the Agars’ collie and the Temples’ boxer. The breeze ruffled her hair, the dimples winked. “I don’t care if it’s a boy or a girl.”

I drove off muttering, “She’s not old enough to have a baby,” though her answer to that one still echoed in my ears.

“All you have to do is look at your own children. You’ll discover that we all grow up.”

As I said, I’ve been doing stories for twelve years. That’s why I’m doing this one. “You’re elected vice-president in charge of Temple,” Al Delacorte wrote. “She’s on our cover. She’s still America’s dream girl. Go back through your memories and tell them about her.”

I knew how Shirley’d wrinkle her nose up at “dream girl.” She’s a matter-of-fact young person, and to herself she’s a happy wife like thousands of others, waiting in a kind of suspended glow for the birth of her first child. Which doesn’t alter the fact that, viewed from the outside, she’s a fairytale.

Say you’re a girl yourself, from ten to twenty. Say you’re lying awake this January night, building castles in Spain. Here’s the whole world to choose from, what’ll you have? Let your fancy roam free, splash the colors as bright as you please, and you’ll still dream nothing more fabulous than what Shirley’s lived.

Like to be in pictures? At 19, Shirley’s been in them for 16 years. That part alone would fill a book, which I’m not writing. But it started from nothing. No movie connections. No ambitious mamma shoving her darling toward the limelight. Just a middle-class family of modest means, and a father who carried snapshots around same as yours did.

Roughly, the beginning divides itself into four scenes. Scene 1. George Temple, manager of a branch bank, showing his snaps to a depositor, who happened to be a dancing teacher. “That’s a cute kid,” she said. “You ought to give her dancing lessons.”

He grinned. “She’s just a baby.”

But he mentioned the incident that night, and Mrs. Temple turned thoughtful. The baby did love to dance. She’d sway her body to the rhythm of radio music, and Sonny, their 13-year-old, would take her hands and trot her around the room. “You know, she’s a little shy with other children. Dancing school might be good for her.”

Scene 2. The day they arrived at dancing school after several months of lessons, to find the other kids done up in their best. Shirley was in her dancing uniform.

“What goes on here, a party?”

“No, some movie director’s coming to look for talent.”

Mrs. Temple hustled her daughter into coat and cap, but the teacher nabbed them at the door. “Oh, let her stay, they’re not taking pictures, just looking—what harm can it do?”

So Shirley stayed with the children, while the mothers waited in another room. “What happened, Prune?” Mommy asked on the way home.

Prune—her mother’s pet name that stuck through the years—chuckled. “I hid under the piano, but they found me. Then they said walk up and down, and what’s your name, and that’s all.”

Four days later, the director called. Would Mrs. Temple bring Shirley in for a screen test? Daddy hit the ceiling. He wouldn’t have the child turned into a little showoff. What finally brought him round was knowing that his wife didn’t care for showoffs either.

Followed a series of shorts. Nothing startling happened. Shirley got some good notices. “A brown-eyed little vamp whose head is a halo of golden curls . . .” “Shirley Temple’s already queen of the troupe, and she’s breaking lots of hearts . . .” But the pictures weren’t important enough to attract much attention, and it might have ended there except for:

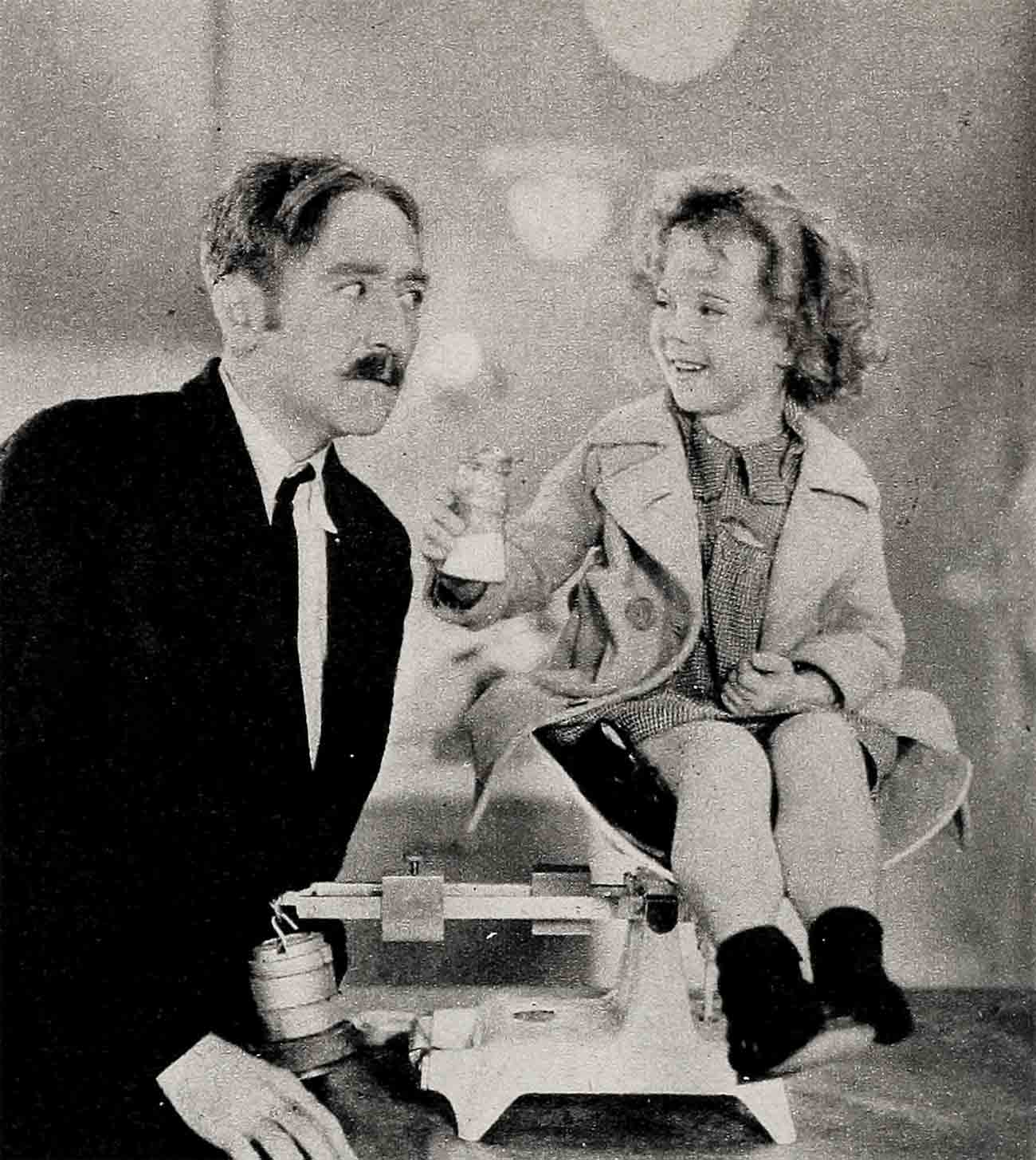

Scene 3. Jay Gorney, a songwriter for Stand Up and Cheer, ran into Mrs. Temple and Shirley in the lobby of the Ritz. He’d seen those two-reelers. “Look, they need a youngster for a spot with Jimmy Dunn in this picture. I wish you’d take her over to Fox.”

“Where do you take her? How do you get in?”

“Ask for Lew Brown. He’s producing for Winnie Sheehan.”

Lew Brown had seen 150 children. He took one look at Shirley. “I want you to take this song home and learn it—”

Which brings us to Scene 4 and the climax. The sound recording room at Fox, crowded with people. Shirley standing on top of a table, singing Daddy, Take a Bow, and then Winnie Sheehan’s office, and Mr. Sheehan saying, “Shirley’s going to be one of the screen’s greatest sensations. A star within a year and after that, anything can happen.”

He was a truer prophet than he knew. When Stand Up and Cheer showed at Radio City, the audiences did just that for Shirley. For four years in a row, she topped all box-office winners. “A worldwide emotion,” somebody called her. Presenting her with a special Oscar in ’34, Irvin. Cobb said: “When Santa Claus did you up in a package and dropped you down Creation’s chimney, he brought the world a beautiful Christmas present.”

By the time she was eight, people were fondly speculating about what she’d be like at 18. Clark Gable said to me once: “They’ll never let her go. They’ll want to watch her grow from a little girl to a bigger one. They’ll follow every stage; in a way she’s their own kid, they’ve adopted her.”

We’re a democratic nation and we pick our own royalty. What Elizabeth is to the British, Shirley became to us—princess of American girlhood.

Gable was right. Shirley was still fifth on the box-office poll when she left 20th-Fox for school. Came a couple of years and a couple of pictures that did no one any good, but her name still made headlines. In Annie Rooney, Dickie Moore kissed her on the cheek. “Shirley Gets Her First Kiss!” blared the papers. (“I never heard so much bother about nothing,” said Shirley.) Through those years of relative inactivity, the fan letters continued to pour in.

David O. Selznick bought Since You Went Away, and asked Shirley to play Brig. Under contract to Selznick, the career went zooming again. When she left Fox, Nicholas Schenk said: “We owe her a great debt. I look forward to the day when she’ll be taking her place among top-ranking adult players.”

The day has arrived. She’s the only child star who ever made it. Her name on the marquee pulls customers in as it did ten years ago. And in bringing her career up-to-date, there’s a final romantic touch that you’d never dream of dreaming in, it’s too far-fetched.

As you know, John Agar’s also under contract to Selznick. He went through a long arduous period of training. Finally John Ford, casting War Party, started looking at tests for someone to play the young West Point subaltern, and stopped when he came to Jack’s. “There’s the fellow I want.”

Later he told Daniel O’Shea, president of Vanguard: “Now I need a girl. Someone like Shirley Temple.”

“Well, why don’t you get Shirley Temple?”

The minute he realized O’Shea wasn’t kidding, Ford made tracks for the phone. Shirley hesitated. I’ll talk to Jack first, Mr. Ford, then I’ll let you know.”

It was the baby of course. Nobody knew about the baby yet, but she couldn’t make the picture without telling Mr. Ford. So she went down and sort of whispered it in his ear.

“Shirley,” he promised, “I’ll carry you round on a feather cushion, if need be.”

So her last part before the baby comes is played opposite her husband. “It’s perfect,” says Shirley. “I chase Jack all through the picture.”

Before she was 12, Shirley’d earned enough to be independently wealthy for life. ‘Remember the giant moneymakers? Little Miss Marker, Little Colonel, Wee Willie Winkie, and on and on. Manufacturers clamored for Shirley’s name on toys and bags, on dolls and clothes and cutouts.

The Temples took their responsibility hard. No product was ever endorsed till their lawyer had made an exhaustive checkup. By the time she was six, Shirley’s financial affairs were such that her father left the bank to take over. George Temple’s no exception to the tradition of conservative bankers. Carefully, he invested his daughter’s money for his daughter’s future. In the interests of her welfare, he and his wife turned down for Shirley at least as many thousands as she made. Not to mention what they turned down for themselves. Gertrude Temple was offered $5,000 to tell radio listeners the secret of Shirley’s success. “How can I take money,” she asked, “for something I don’t know?”

5 bucks for sodas . . .

So Shirley became a million-dollar industry. She had a guard, but to her he was just the chauffeur. She got five dollars every two weeks, most of which went on soda pops for herself and pals. “Is that my salary, Mommy?” she asked once.

“Oh no, you make quite a bit more, but Daddy’s saving the rest for when you grow up.”

“That’s good. I’ll need it to buy my vegetable market.” An ambition that lasted a good six months.

With the Temples, home and family came first. To say that their life was unaffected by Shirley’s success would be silly. To say that its spirit remained unchanged is true. The only thing they splurged on was a new home. Driving up Sunset Boulevard one day, they stopped at a wooded hill overlooking the sea. Shirley ran ahead. At the base of a tropical bush, she found a family of quail. “Here’s where I want to live. The birds like it here.”

There the new place went up, with its pool and terraced gardens, its badminton court and playhouse and everything to delight the heart of a child. There Shirley lived till she and Jack built their five-room French Provincial cottage next door. Now the guest room will be a nursery. In the flagstone court at the Temples’, the bush still stands where a little girl knelt enchanted on a sunny afternoon. The little girl made a fortune. But her great pride today is that she budgets her household within Jack’s income.

If it’s fame you’re after, Shirley’s had the world at her feet. No child ever had a better excuse to become unbearable. Shirley stayed lovable.

The movie greats she acted with were just a lot of friendly people to Shirley. Orson Welles was the only one who ever made her eyes pop, and that was on account of his broadcast from Mars. To reward him, she let him win from her at croquet. But her contacts weren’t limited to the movie world. Statesmen, artists, scientists—if they came to Hollywood, most of them asked to see Shirley Temple.

One spring in ’38, Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt, the First Lady of those days, came, and wrote in her column: “She’s one of the most charming children I know. I marvel at her mother’s achievement in keeping her unspoiled. Shirley told me she was coming to Washington to see the President soon, and I hope she will not delay her visit too long.”

When the President of these United States keeps his Secretary of the Treasury waiting, in order to spend ten minutes with a child, brother! that’s fame. It happened the following June. Mr. Roosevelt and Shirley discussed sailboats, fishing and children. She told him about the tooth she’d lost in a sandwich. He told her not to feel too badly. “You know, Shirley, I’ve lost a few of my own, and it doesn’t make a bit’ of difference. I still manage to say all I want to say.”

She emerged on a roomful of reporters, popping questions. What had they talked about? “I was so excited, I’m afraid I can’t remember everything, but when I said, ‘Will you please sign my autograph book?’ he said, ‘Sure, Shirley, I’ll be glad to do that.’ ”

She showed them the book. “To Shirley, from her old friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, June 24, 1938.” His wife’s name was on the same page. “Mrs. Roosevelt left a space for the President when she was out at the studio that time. It’s a very important book now.”

“Did you like him, Shirley?”

“Oh yes, he was simply grand.”

“Did he like you?”

That chuckle again. “I don’t know, I didn’t ask him.”

She spent a day at Hyde Park with the Roosevelt grandchildren. “It’s awf’ly nice of you folks to invite me here,” said Shirley. Mrs. Roosevelt wrote another column about her simplicity. She didn’t mention the President by name, but said “a gentleman present was her willing slave for the afternoon.”

Darling of her countrymen, and their President “her willing slave,” if only for an afternoon. Try that in your dreams, girls.

the simple life . . .

On the other hand, you may be for the simple life. The normal round of home and games and school and dates and fun. Shirley must have missed all that, you say. A girl can’t have everything.

Shirley didn’t miss it. When the drums began beating after Little Miss Marker, the Temples eyed each other, incredulous and scared. George was the first to recover speech. “Looks like we’ve got a movie star on our hands,” he gulped. “What’ll we do now?”

What they did through all the years that followed was to put Shirley, the child, ahead of Shirley, the star. Mrs. Temple will never stop being grateful to Winnie Sheehan, because he insisted that little Shirley have her own bungalow, where she ate and played and studied. It was he who ruled that she never be taken to the studio commissary for lunch. “You can’t keep people from making a fuss over her, and enough of that’ll turn anyone into a smart-alec.

Mrs. Temple was an old-fashioned mother, who believed that no child should consider herself too important in the scheme of things. Once there was a great to-do over whether to spank or not to spank in Wee Willie Winkie. “What’s so awtful about spanking?” Mrs. Temple inquired crisply. “I’ve done it myself once or twice; Shirley’s no different from other children.” So June Lang, as her screen mother, spanked her, and Shirley giggled to her own mother: “She never hurt me a bit, but I bet her hand stings.”

She had as much time to play as any child who goes to school; she never worked more than 25 weeks a year, averaged between two and three hours before the camera, and thought it a joke when people asked if she minded working. The only thing that ever bothered her were people who went gooey and wanted to kiss her. But as far back as I can remember, there was a dignity in her that served as its own protective barrier. Years later she said, “I’d keep calm and think about my rabbits or something, and that way Id feel safe in my own private life.”

In the backyard behind her studio bungalow were sandpiles and swings and boxes for the beloved bunnies. Her stand-in and closest companion was Mary Lou Isleib, daughter of a banking associate of George Temple’s. Mary Lou was a bridesmaid at Shirley’s wedding, and this year Shirley served as attendant at Mary Lou’s.

Loved and looked after like any small daughter, she was definitely no star in the home. Her two brothers’ healthy attitude toward her was best summed up by Jack. “Are you Shirley Temple’s brother?” he was asked.

“No,” he snapped, “she’s my sister.”

She raided the pantry, made mudpies—Mom found her selling them at the gate one day for ten cents apiece—and became the hero of her gang when she tripped on an electric wire and got a black eye. She adored the Lone Ranger, sent boxtops to get her into the club, and got an answer back, saying little girls shouldn’t tell fibs about their names. “What’s wrong with my name?” she demanded indignantly, while Mom hastened to iron that one out.

She grew older and joined the Campfire Girls and rode a bike, no hands, and started ribbing her brothers about their dates. And in 1940 she was enrolled in the Westlake School for Girls. Her mother had picked Westlake for several good reasons—among them, that the parents of many of the girls were connected with pictures, and a movie star was nothing special to them.

tight shoes . . .

It was super from the start. The French teacher introduced her to a class of about twelve, and one of them came forward and took her by the hand, and said: “I’ll take care of Shirley.” That was Betty Jean Lail, another bridesmaid at the wedding. It was with her classmates that she went to her first formal. She got home at eleven, complaining happily that her feet were killing her.

The girls called her Butch, and the only time they ribbed her about the movies was at Senior Initiation, when they made her do an imitation of Shirley Temple doing the Lollipop song. Otherwise, pick any schoolgirl you know, and that was Shirley. Sweaters and skirts and saddle shoes till Friday and Saturday nights rolled around; then moaning for glamor hairdos and “Oh Mother, that lipstick’s not too exotic, all the girls use it.” Typing themes by what she called the Columbus system—discover and land—studying to the blast of the radio, jabbering endlessly on the phone. Bringing new boy friends home, so the folks could give them the old once-over, getting a crush on Van Johnson, and on the way she felt when she found she’d turned down a dance with him. One of the girls asked if she’d like to trade dances, and Shirley said no, she had such a smooth partner. Then lo and behold, the other girl’s partner was Van, and Shirley stayed mad at herself for a week.

On a June day in ’45, she was graduated from the Westlake School with her class. Forty-two white-gowned girls walked down a flower-banked lane, and received their diplomas. Gertrude Temple’s thoughts flew back to another day.

“Looks like we’ve got a movie star on our hands. What’ll we do now?”

Their first job had been to protect her against influences that might distort her natural growth into womanhood. That job was done now, and well done.

* * *

All this, and heaven too. All this, and a storybook romance, and two young people loving each other more dearly at the end of two years, and a baby coming before Shirley’s 20th birthday.

She was fifteen the first time she looked up at Jack’s six-foot-two. A bunch of them were down at the Temple pool, and Ann Gallery had brought the young buck sergeant over. Twenty-two doesn’t take fifteen too seriously. This particular fifteen was dating about six nice boys, and marriage was far from her mind. Yet she wasn’t quite seventeen when she got her ring, and not seventeen and a half when she said, “I will.”

“How can you be sure it’s love?” somebody asked her.

“When it’s love, it’s love, and you don’t need a chart to tell you.”

He was the dream prince all right, tall, blond and handsome. Better still, with tastes and standards like hers, and the same solid background. Even the difference in age was perfect. Shirley’d always gone for older men.

They meant it when they promised not to marry for two years. But suddenly the war was over, and it looked as if Jack might be sent overseas with the occupation troops. “If he has to leave me,” said Shirley, “I want him to leave me as his wife.”

Life had showered her with all its gifts, but I assure you that Shirley’s wedding day meant to her exactly what yours would mean to you—the same radiance, the same hopes and visions.

At home she went round in circles, while Mom answered millions of last-minute phone calls, and everyone looked kind of numb. They must have been numb, because on the way to church, they suddenly realized they’d forgotten brother George, who’d gone to pick up his girl. In the Brides’ Room at the Methodist Wilshire Church, Howard Greer, who’d designed all the wedding clothes, was waiting with his assistants. Under Mom’s supervision, Shirley and her bridesmaids were dressed. “Is Jack here?” Shirley’d ask every two minutes.

Outside, the streets were jampacked. You couldn’t keep the crowds away from their adopted child. But within the candle-lighted church, lovely with pink roses and looped blue ribbons, everything was as Shirley wanted it—not a Hollywood circus, but a quiet gathering of close and valued friends.

Mrs. Temple in gray, Mrs. Agar in gold crepe, took their places. Jack stepped to the altar, with Shirley’s brother Jack as his best man. I’ll Be Loving You Always dissolved into the Wedding March. Behind her bridesmaids in periwinkle blue, behind Mims, her sister-in-law and matron of honor, came Shirley on her father’s arm. Her gown was of ivory satin. As she joined Jack at the altar, she looked up at him and smiled.

“Dearly beloved,” began the Reverend Willsie Martin.

When he finished the ceremony which made the sweetheart of millions the bride of John Agar, her husband turned and took Shirley into his arms. Not even Gable, as one onlooker put it, ever kissed a girl with greater authority.

marrying a legend . . .

Of course there was lots of chatter at the time. Wise talk about a boy, who’d never had a thing to do with pictures, marrying not merely a fabulous movie star, but a legend.

“I’m not marrying a legend,” smiled Jack. “I’m marrying my girl.” He said it simply—and meant it.

Whatever the pitfalls, they haven’t snared these two, and to them the reason’s simple. “I don’t like giving advice,” said Shirley once. “But since you ask me, I think the secret of any marriage is love. Nothing else matters.”

They love each other enough. They’re planning a family of three, though Jack’s inclined to four. “Maybe we’ll compromise,” says his wife, “and make the last one twins.”

At the moment she’s busily knitting on a pink and white afghan. If you point out that pink’s for girls, she replies firmly: “Our son, if he turns out to be a son, will use it and like it. Because his mother has a pretty strong notion that pink’s for babies.”

So there you have her up-to-date, the girl who’s lived your dreams. To me, the top miracle of the lot is that Shirley Agar sounds sweeter in her ears than Shirley Temple, and what she wants most out of life is to go right on being her husband’s dream girl.

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948