Look Homeward, Ingrid

Rarely has a woman of sensitivity and intelligence paid such a cost!y price for happiness as Ingrid Bergman, who, in the summer of 1948, left husband, home and Hollywood career to become first, a target for sensational headlines throughout the world, and then the wife of Italian producer-director, Roberto Rossellini. How often she must have pondered the words of the great Italian writer, D’Annunzio: “Love is a terrible weapon, worse than the bomb. It burns, destroys, leaves nothing behind it.”

But there are exceptions. even to the words of the poets. Ingrid Bergman’s spirit not broken—by the most bitter of life’s tests. The fruits of her love often may nave tasted bitter-sweet (who but she knows bow many moments of regret and remorse she has lived?), but by sheer force of character and a stubborn faith in the rightness of her actions. she has emerged victorious.

But all that is in the past. It is the present and the future which now occupy Ingrid Bergman’s thoughts and plans. After six years of making films exclusively with her husband, Roberto Rossellini—in which she played everything from a fisherman’s wife to an unbalanced neurotic—she has returned to the international fold.

As the tortured woman who tries to prove she is Anastasia, the youngest daughter of the last Czar of Russia, Ingrid is starring in her first American film since she left Hollywood in 1948. “Anastasia” has been adapted from the successful Broadway play, and Twentieth Century-Fox’s new production head, Buddy Adler, paid $400,000 for it—indicating how much he thinks of it.

Most of “Anastasia” was filmed in London, with some location shots in Paris and Copenhagen. During part of the time that Ingrid was working in London, Rossellini was in Jamaica, on location for “Seawife,” his first British film (to be released by 20th), which stars Joan Collins and Richard Burton. However, just before the shooting began, Rossellini bowed out of the picture, because of script disagreements, and rejoined Ingrid in London.

Recently, in one of her rare interviews, Ingrid talked frankly and honestly about what has happened to her in the past eight years. As she gazed across the lunch table in a London restaurant, her sparkling, clear eyes radiated health and contentment.

Explaining Rossellini’s premature return to London from Jamaica, Ingrid said, “My husband is not used to working in the traditional manner with a finished script, as he must in this picture. He prefers to be free to change his story line and characterizatons as circumstances and events dictate. He uses his camera, rather than dialogue, for conversation.

“Actors are often impatient with his methods,” she added, smiling mischievously as she named one star who flew back to Hollywood in a rage after making a picture with Rossellini. “I, myself, found it rather difficult at first, but I so yearned to make Italian pictures when I went to Italy. You see, to him, actors are less important than the setting.”

Ingrid reviewed her husband’s career with the pardonable pride and subjective loyalty of a devoted wife. She has proved that loyalty time and time again. For years she refused to consider any of the many enviable contracts for movies, plays and TV shows offered her, if it meant ending her film partnership with Rossellini.

Nevertheless, her steadfast loyalty must have been jolted many a time, as their joint efforts met with continual critical and financial setbacks. But never once, by word or gesture, did Ingrid veer from the path she had chosen—to share her life and her great talents with the man for whom she had defied the world. . . .

Ingrid refused the dish of bread and took up a forkful of scrambled eggs. “No, I don’t diet,” she said. “I eat whatever appeals to me. I will admit this is a bit of relief from the Italian dishes I’m accustomed to. When my husband is with me, he insists upon eating Italian food. It doesn’t matter in which country we may be.

“This is the first time we have been separated from our children (Robertino, six, and the twins, Isabella and Ingrid, four) for any length of time,” she went on, “but we could not deprive them of their summer on the sea. It is so lovely now at our beach home in Santa Marinella. They can swim every day, and they have their dogs and birds to play with and keep them company. It would have been unfair to bring them to London and Paris and set them down in a hotel in the middle of the summer.

“But,” she smiled, “we speak to them on the phone almost every evening, and my husband insists that they send us a telegram every single day, telling us what they have done. Of course, it is difficult for young children to think of something different to say that often, and sometimes they forget to wire us. When that happens, Roberto calls them because he is worried something may have happened to them. Frankly, he calls them even when we do receive the telegram.

Ingrid’s smile injected a ray of sunlight into the gloomy interior of the hotel restaurant. More stunningly handsome than ever, her flawless skin untouched by a trace of make-up, except for a dab of lipstick. she was the very image of the Ingrid Bergman of legend, blooming with health and vigor and natural beauty.

She was slimmer than Hollywood remembers her, and tastefully dressed in a Paris-styled gray silk suit and her customary flat-heeled shoes. Her nails, cut short, showed not a hint of tinted polish. On her left hand, she wore a plain gold wedding band; on the small finger of her’ right hand was a large dinner ring which matched her necklace. Her silky blond hair was twisted into a becoming chignon.

Anastasia” is the second movie Ingrid has made without her husband in the The first, which she finished last spring, was “The Red Carnation” (to be released by Warners), directed by Jean Renoir.

It is doubtful that Ingrid would have agreed to make “The Red Carnation” if Rossellini hadn’t urged her to do it. “Jean Renoir and I are old friends,” says Rossellini, “and I think he’s one of the greatest directors in the world. I told my wife she couldn’t turn down a chance to make a picture for him.”

“There was no battle or great struggle on my part to convince Ingrid to make ‘The Red Carnation’,” Jean Renoir told me, when I cornered him studio, where he was busily editing the in his Paris film. “It resulted from an easy conversation with her and Roberto one day last summer. when I was visiting them.

“She said to me then, ‘If you find a story I like, I’ll be delighted to make it.’ So I wrote ‘The Red Carnation,’ a story about a beautiful, impulsive princess, a breaker of men’s hearts. Ingrid liked it, but I thought it was too dramatic. I thought her first international picture, after so many years in Italy, should be a comedy. So I rewrote it, and she liked the second version, too. It was as simple as that.”

As soon as Ingrid and Rossellini started working on separate projects, the rumors were revived that they would never work together again. “Nothing is further from the truth,” said Ingrid, as she sipped her glass of milk, making a wry face when discovered it had been boiled and was still lukewarm. “Oh, what I wouldn’t give for a glass of sweet, cool milk as I had in America,” she sighed.

“Getting back to my husband. Of course, we’ll make a film together, probably next year. It might even be a comedy. Roberto has never directed a comedy before, but he knows I so enjoyed making ‘The Red Carnation,’ he is going to concentrate on lighter themes.”

Hand-in-hand with the stories about the Rossellinis’ professional break-up have been the rumors about a marital split-up. They have denied this so often, singly and together, privately and publicly, that they have just about decided theirs are lone voices crying in the wilderness. Rossellini, usually easygoing and affable, hopes to quash the rumors once and for all by stating, with great emphasis, “My wife and I are happy together, professionally as well as personally. These pictures we are making apart are just a short interval in what we hope will be a long life together, during which we will collaborate on many more films.”

“This working apart,’ says one of the Rossellinis’ close friends, “is probably the best thing in the world for their marriage. It will give them a chance to breathe, each in a different artistic atmosphere, and to re-evaluate themselves, artistically as well as personally.”

“Ingrid and Roberto,” says another intimate friend, “were destined to meet and love each other. Of course, they are different in character. He is typically Italian, volatile and violent, but with a Latin subtlety. Ingrid is direct and methodical. If confronted with a brick wall, Roberto would get to the other side by going around it. Ingrid would crash right through. But they are both aristocrats, and they complement each other perfectly.”

Nevertheless, one of them has only to make a public appearance, unaccompanied by the other, and the tongues begin wagging again. Last spring, at the Cannes Film Festival, Ingrid attended a cocktail party alone. This, to the gossips, was undisputed proof that she and Rossellini were breaking up. The truth was that Ingrid had arrived by train from Rome, and Rossellini had followed her down in his Ferrari racer. Because of the children, Ingrid will never fly or accompany Rossellini in his fast racing cars. But they are rarely apart for very long.

When costume fittings for “Anastasia” required Ingrid to be in Paris, while Rossellini had to stay in London, she commuted back and forth between the two cities every other day. “I’m so used to trains,” she laughs, “I sleep better on them than in my bed.” On the first day’s shooting of “Anastasia” in Paris, Rossellini left pre-production conferences on his own film in London to be at her side.

That first turn of the “Anastasia” cameras might be called an historic occasion. At least, that seemed to be the opinion of the scores of onlookers, many of them big names in Hollywood, who crowded the banks of the Seine that night.

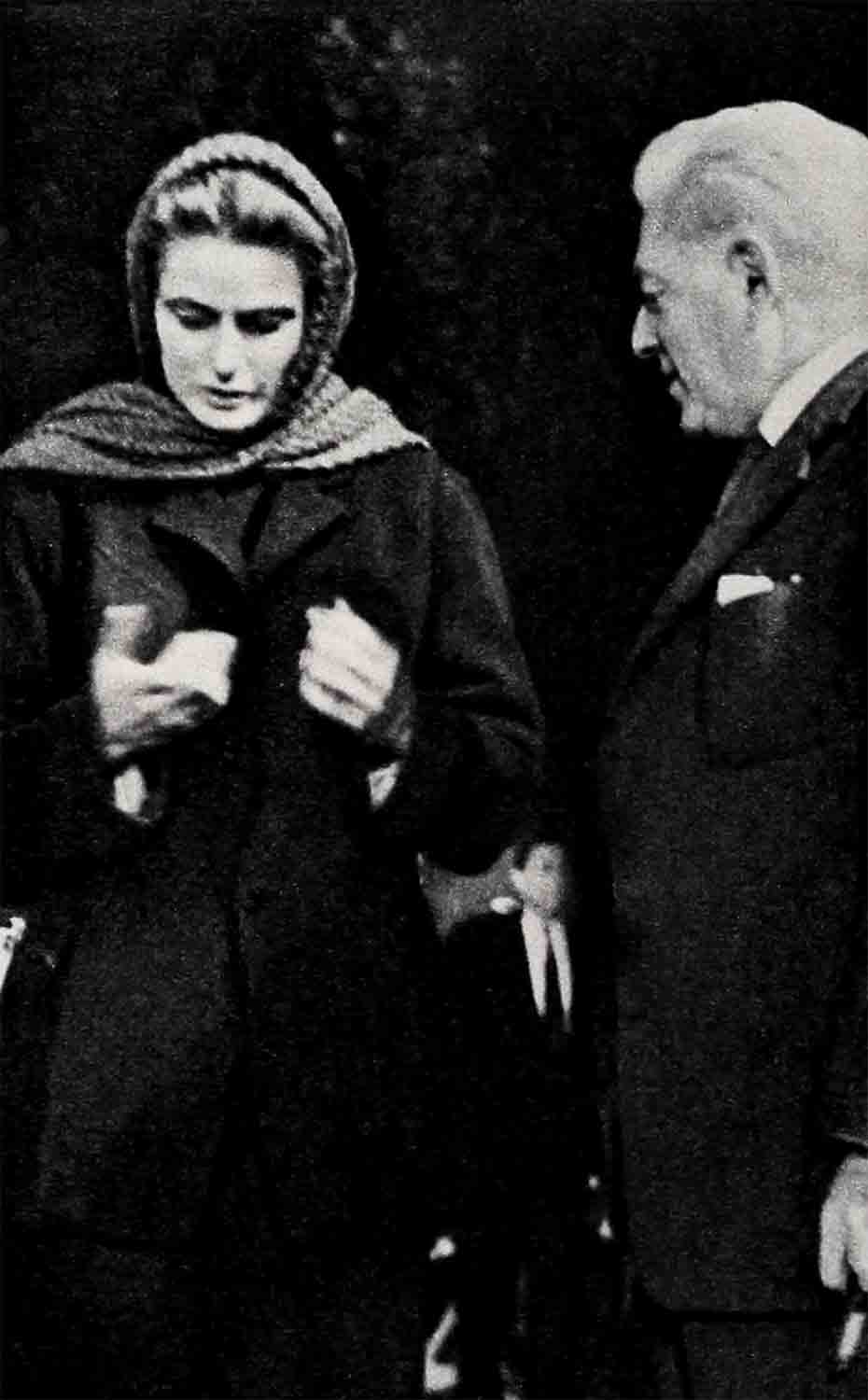

Director Anatole Litvak paced up and down the bridge waiting for the rain to subside. Ingrid was finishing her make-up in her portable dressing room. The haggard creature who finally emerged was difficult to recognize as Ingrid Bergman. Make-up had deformed her beautiful face. Her eyes were heavy and dark with fatigue, and her skin was drawn and matted in a thousand lines. She wore an ill-fitting old coat and a shapeless skirt. A knitted shawl clung to her head.

Ingrid chatted gaily with her husband and co-star Yul Brynner until there was a sudden break in the rain. Then Litvak hurried back to the set and gave final instructions to the crew. He turned toward Ingrid, smiled, and nodded his head. “On set, Ingrid dear,” he said quietly. A hush fell over the crowd.

Ingrid Bergman, once the world’s highest-paid actress and often named its greatest, stepped forward. She was alone, face to face with an American camera for the first time in eight years.

But she was no longer Ingrid Bergman. She was Anastasia—sick, alone, almost delirious from weariness and misery. An indescribable horror lurked in the shadows of her eyes. If only she could end it all. The Seine, melancholy and forbidding in the darkness, beckoned to her. She swayed almost eagerly toward it.

What need was there for dialogue? Words were as superfluous here as in a symphony. Ingrid’s eyes and gestures and movements told the story.

“Cut!” cried Litvak. The scene was over. Ingrid walked slowly toward her chair and sat down. Muffled murmurs spread through the mass of spectators, most of them men and women of the acting world.

“Man, oh, man, what an actress!” muttered a bystander.

Jean Renoir puts it this way: “Ingrid is a born actress. Believe me, there are very few of them. She is the only one since Garbo who can play any role with perfect dignity. And she never plays herself. She analyzes every line and situation, and then submerges herself so completely into the personality of the character she portrays that she becomes that person.

“For Ingrid, it is life which is all make- believe, a big show in which she plays a part,” says Renoir. “But what is real for her is not life, but the theatre. There she does not play a part, she belongs.”

The need to mold a character according to her own conceptions explains Ingrid’s reluctance to do any personal research on the woman who was Anastasia. “I’ve been told there are dozens of books about her,” Ingrid said, “but I don’t want to read them. Nor do I want to talk with the woman now living in Germany who claims to be Anastasia. It would just confuse me. You see, I am Anastasia.”

This was said without the slightest note of affectation or over-confidence. It was so very simple—she was Anastasia; she lived the role each second that she was before the cameras. She knew how Anastasia would react to a given situation, because she and Anastasia were one indivisible being.

This unqualified dedication to her art, the primary requisite of a great artist, has dominated Ingrid’s life since childhood. “At the age of twelve I already knew I would be an actress,” she says.

She was a lonely child in her native Sweden. Her mother had died when Ingrid was a baby, her father when she was twelve. She was shy and awkward and self-conscious about her height. She found solace and comfort in books and poems, and the imaginary characters who peopled them became her friends and confidants. Then, at the age of twelve, she visited a theatre in Stockholm, and she knew then where her destiny lay.

“If I could no longer act,” says Ingrid, “I think I should stop breathing.”

The main reason for Ingrid Bergman’s greatness, both as a woman and an artist, according to Jean Renoir, is her complete honesty that will make no compromise with life or love.

“Ingrid cannot lie any more in her work than she can in life,” says Renoir. “She is as straight as a steel sword. It would never occur to her to beat around the bush. Where others try to compromise and pacify, she comes straight out with the truth.

“I remember her reaction to my film, ‘French Can Can,’ which she saw in Paris last year. ‘Jean,’ she told me, ‘I don’t like your picture, and she proceeded to tell me why she didn’t like it. How many people do you find so frank and direct? She didn’t try to soften the blow, she gave it to me straight. Ingrid has distinction and dignity, but the source of her pre-eminence is her honesty.

“Everyone on this earth has a purpose, and a task to perform,” Renoir continues. “The people who serve your coffee and your wine, the dancers in the chorus, I love them, all of them. But Ingrid, now you’re talking about someone very special. She has her own place in this world, a place ’way up there,” and the director pointed skyward, “up on a pedestal. You know, there aren’t many like her; she’s unique.”

Mel Ferrer, who appears opposite her in “The Red Carnation,” has this to say: “Ingrid is one of the few members of a fast-disappearing race of originals. Marlene Dietrich, with whom I also had the good fortune of working, is another. Ingrid, Marlene, Garbo, there is nothing average about any of them; they belong to themselves. No one else can touch them “Ingrid is more than an actress,” Mel adds, “she is a creator. I have seen her play one scene in two or three different ways, and each one was as valid and logical as the other. She had a fresh approach because she was doing more than interpreting, she was creating.

“And she loves every minute of working,” says Mel. “She has an extraordinary sense of participation; she can’t stand to leave the set in-between takes, just likes to stand around and chat with the crew and remain a part of the production. She has a great sense of fun, too. Making the film with her was a round of laughter, off-screen as well as on.”

“Anastasia” didn’t get under way without Ingrid indulging in a little personal joke. When Anatole Litvak arrived for the first night’s shooting, he found a tiny ladder, all tied with a pretty ribbon, next to his director’s chair. “Now you can direct me without having to look up at me,” five-foot-eight Ingrid laughed. Usually she plays with her shoes off. “The Red Carnation,” in which she played opposite six-footer Ferrer, was one of the few films during which she was able to keep them on.

Skipping dessert, Ingrid took a cigarette out of her bag and lit it. “I’m on vacation when I work,” she said. “When I’m not working. I’m obliged to lead a very active social life. Friends are always calling me to go to tea or shopping, or to cocktail parties. I have a horror of social functions. But when I’m not making a picture or in a play, I have no excuse. I must attend them. Now I can turn them all down without hurting anyone’s feelings. Oh, it’s wonderful to be back in harness. I feel as if I had suddenly come alive.”

Mel Ferrer, seeing her recently for the first time in months, commented on her appearance. “Tell me, Ingrid, how do you manage to look so young and beautiful?” he asked. “If it’s true,” Ingrid answered with a laugh, “perhaps it’s because I’m back at work.”

Her taste for activity was being gratified—for, at the same time she was making “Anastasia,” she was preparing for Tea and Sympathy,” which she will play in French this fall on the Paris stage.

However, Ingrid figures as more than just the star of this play. She has helped with the translation from English into French, advising on the decor and costumes, and serving as a general technical consultant on American customs.

“The translator has been very understanding about my suggestions,” she said. “His first adaptation was too French in text and slant. American plays have and I feel that our one chance to bring this off is to retain an essentially American atmosphere, rather than simply translating the plot and characters to French soil. Fortunately, I know American slang and dress and reactions to certain situations, so I was able to make some recommendations.

“Of course,” Ingrid laughed, “it would help if my French were just a little better.” Actually, Ingrid speaks French fluently, with only a hint of the same Swedish accent she has in Italian and English. Since her marriage to Rossellini, she has become an accomplished linguist, and the entire family converse with each other in Italian and French, and on occasion, in English.

“I can’t tell you how much this play means to me, and how badly I want it to succeed,” Ingrid continued. “The theatre is very important to me. After making films for several years, I find it essential to return to the stage. During he ten years I lived in America, I made it a rule to do a play every four years. I need the personal contact with the audience, the nightly absorption in the role which excludes all outside influences. After a year on the stage, I can return, fresh and stimulated, to the screen.”

Not the least of the advantages of the theatre is the free time it allows Ingrid to be with her children. “This winter I shall have the entire day to spend with them,” she said. “I’ll put them in a Paris school, and we shall probably look for an apartment, although we have no serious objections to hotel life, except for the inconvenience of not having a kitchen.

“The children are used to hotels; they’ve been living in them since they were babies. As a matter of fact, they are rather fond of The Raphael in Paris, where we stayed for many months during the shooting of ‘The Red Carnation.’ In their little minds, that hotel has become a Paris landmark, and they are quite certain that the Eiffel Tower, which they call the Raphael Tower, is somehow connected with the hotel. And it is so very convenient to the children’s playground in the Bois de Boulogne. They have a grand time there, riding on the miniature trains and inspecting the zoo. I don’t really think it matters to children where they live—in an apartment or in a hotel—as long as their parents are there. Being together is what makes a home.” As she said this, the slightest trace of seriousness crept into Ingrid’s voice; until then her tone had been rather light and bantering.

The rejuvenation of Ingrid’s career has not changed her basic views. She is first and primarily Signora Rossellini, wife and mother, and her career will always take second place.

“ ‘Anastasia’ was originally to have been made in the spring, so that the children could be with me,” she said. “I don’t know if I would have agreed to it if I had known we would be separated. My husband has postponed a trip to India several times because he can’t bear the thought of leaving the children.”

Ingrid has worked out a program of play and study for young Robertino and the twins, which they follow under the supervision of a nurse and governess, whether they are in the Rossellini apartment in Rome’s smart residential Parioli section, their summer home in Santa Marinella, or on the road with their traveling parents. No matter how hectic her schedule, Ingrid manages to be with her children a great part of the time. They never have the impression that they take second billing to a busy career.

An eye-witness describes a scene which was a daily occurrence in the Rossellini hotel apartment in Paris last winter. Ingrid Bergman, her long legs curled under her, sat in the middle of the floor. Around her were gathered Robertino, a handsome, intelligent youngster; the twins, one a replica of Ingrid, the other just like Rossellini; and Renzo, Rossellini’s son by his first marriage. As the children laughed and clapped and shouted, Ingrid deftly manipulated two puppet dolls and recounted in Italian the adventures of the fierce bandit and the brave policeman.

“More, more, Mother!” cried the children in unison.

“No,” said Ingrid, “it is time for your walk to the Bois, and I must take my French lesson.”

Adherence to a tightly regulated schedule gives Ingrid leisure hours with her youngsters and permits her to indulge in her pet pastimes: the theatre and old- time movie classics. She is a member of a Paris cineclub, where she has often led bull sessions on the art of movie-making; she is a regular attendant at the UNESCO showings of silent-movie classics; and she has seen every play on the Paris and London boards.

“Theatre-going in Paris can sometimes be a weary experience,” laughed Ingrid, “especially for anyone with legs as long as mine. The seats are small, and the space between aisles very narrow. The other evening I saw ‘War and Peace’ in German at the Drama Festival, and I gave up after three hours. I was squirming all night.”

Putting action to words, Ingrid demonstrated her ordeal by winding her legs around the table, then curling them up behind the chair, and finally, turning completely around to face her neighbor.

Her chuckle was warm and spontaneous. It invited participation. The other lunchers turned to look at this magnificent woman whose gay laughter rang out like a delicate bell. Everyone recognized her immediately, but Ingrid paid no attention to the stares and whispers.

It was time for coffee—and also for the question. Twentieth Century-Fox made no bones about wanting Ingrid to make a trip to America to publicize “Anastasia.” Would she come?

“Of course, I shall come, if they want me.” Her answer was as straight-forward and direct as the gaze that accompanied it. “Naturally, if it’s in the winter, they’ll probably have to bring along the whole Paris ‘Tea and Sympathy’ troupe.” She smiled good-naturedly, and her smile broadened to a wide grin, and her eyes sparkled when she learned that 20th was planning to release the film in time for the 1957 Academy Awards. “How wonderful!” she exclaimed.

There was not a trace of ill-feeling or bitterness in Ingrid’s voice at the mention of Hollywood, and the possibility of her return. And yet, how natural it would be for her to harbor a bit of resentment about the way she had been censured.

As one of her associates says, “There is not a grain of malice in her whole body.”

Hollywood will undoubtedly play an active role in Ingrid Bergman’s future projects. Paramount wants her for the screen adaptation of “The Chalk Garden,” he successful Broadway and London hit. “I had been keeping their offer a deep dark secret,” Ingrid confided, “and then one day I read about it in an Italian paper. I contacted the Paramount office and assured them I hadn’t let the cat out of the bag. ‘Oh, no,’ they answered, ‘we released it ourselves.’ ”

Ingrid has not yet made up her mind about it. With characteristic honesty, she explained the reason for her indecision. “I saw the play in London several times, and although it is a fine play, I frankly don’t think it will make a good movie.”

Now that Ingrid has shown her willingness to work with others besides Rossellini, she has been flooded with propositions for movies and plays. However, she hasn’t made up her mind about any of them. Jean Renoir admits that he would like to make another picture with her, in Hollywood, if possible. Ingrid confesses she would like to make another film in France, but as she says, “I would like this one to be exclusively French, and not a double version as “The Red Carnation’ was.”

Then, of course, there is the project nearest her heart, making a picture with her husband, which they are likely to do after his return from India. “If he ever gets there,” Ingrid commented with a smile. “He has been invited by the Indian government to do a series of documentaries, and he has his heart set on doing it. But there was always some reason for his postponing: his reluctance to leave the children; the heavy rains in India. At least, I have one comfort—he won’t be able to drive fast, as he will have to go in a jeep.” Rossellini, in his usual defiance of convention, was planning to make the entire trip from Europe to India by car, carrying all his equipment.

“Of course, it is difficult for me to make many plans at this time,” Ingrid explained. “I haven’t the faintest idea how ‘Tea and Sympathy’ will turn out. It may close after the first week—or, if we’re lucky, it may run all season. At any rate, if it does, it’s going to be a lean winter. The French theatre doesn’t pay very much,” she chuckled, almost to herself.

Several years ago, when the Rossellinis presented Honegger’s operatic version of “Joan of Arc,” it was a financial and artistic success everywhere except in Ingrid’s native Sweden. The opera was particularly successful in France, where Saint Joan and Ingrid are both revered with almost equal fervor. Queried about any plans to revive the opera, Ingrid laughed and said, “Oh, it was a great run, but I might be too old to play ‘Joan of Are’ by the time I’ll be free from other plans.” Not the least of these “other plans” is her proposed appearance on Ed Sullivan’s TV show this fall.

Not for many years have Ingrid’s personal and professional prospects been so bright. After passing through a forest of darkness she has emerged onto a path of light and hope.

Ingrid glanced at her watch. “Heavens, it’s getting late,” she said. “I have an appointment with the fellow who is translating ‘Tea and Sympathy.’ I’m afraid I’m spending as much time on that as I am on ‘Anastasia.’ ”

She stood up with a natural grace that others achieve only under the glare of kleig lights. Her handshake was firm and friendly; her smile, warm and sincere. As she left the room, it was as if a window had been closed against a gust of fresh, cool air.

Long after Ingrid had left, I found myself still thinking about her, and I couldn’t help feeling I had spent several hours with a very remarkable woman.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956

No Comments