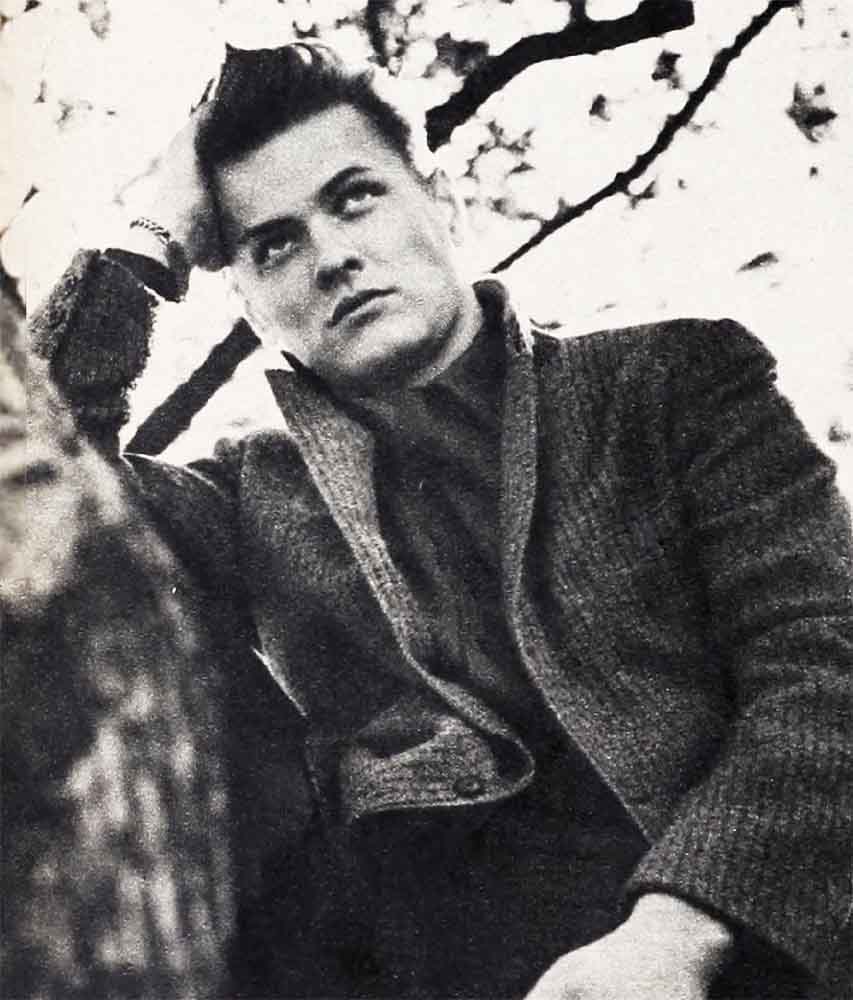

Determined Davalos

Every evening last fail at a quarter past five, a neat, well-built young man would rush past the ticket booth of the Trans-Lux Theatre on 85th Street and Lexington Avenue, throw a quick hello to the girl behind the glass window and slip into the side entrance of the theatre. Fifteen minutes later, in his usher’s uniform, he was as indistinguishable to the patrons whose stubs he collected as any other dark-suited Ne w York usher.

Yet, six months later, these same patrons, plus a few million more, were plunking down money to see this young man, Richard Davalos, in a dramatic movie hit called “East of Eden.” As for ex-usher Davalos, he was still counting movie stubs, but with lots more personal interest. For as “East of Eden” made boxoffice thunder, he saw each ticket sweep him nearer and nearer to stardom—and to a lifelong dream.

Dick’s dream began years ago in the apartment-crowded Bronx, where he was “boarded out” with strangers. He was six years old. Times were hard and words like “depression,” “out of work,” “tough break,” were all too often beard in this home and others which he visited. He knew, too, that one day in the past, when he was still too young to remember, his father left home and never came back. This left its mark and, even today, Dick cannot bring himself to discuss his father. “I don’t remember him,” is all that he’ll say.

His mother, searching for a means to feed herself and her child, took a job as a hairdresser in a New York beauty parlor. Her hours were long, so Dick was boarded out. Shy, sometimes rebellious, more often frightened, the little boy reached out for comfort against the fears he felt in the small, strange room which was now his home. His prayers were not for boyish fears, like overcoming a fear of the dark. At six, Dick Davalos had man-sized nightmares—of being unloved, unwanted, of being a nobody, of insecurity. For a boy with no choice for the present, he looked to the future. One day he discovered a world into which he could escape. A world in which fear and loneliness seemed hardly to exist. It was the world of make-believe.

“I was six years old when I played the Prince and the Magic Mirror in ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ in a class play at the Crestlea School I went to,” says Dick today. “But from that day— except for a brief time in the Navy—I knew what I wanted. I had a blind faith in myself—I had to, no one else did. And somehow, through all those years, I held onto the dream that some day I would be a good actor. A pretty big dream, you’ll have to admit, for a kid born in the Bronx.”

But while the Bronx was a long three thousand miles away from the nearest Hollywood set, it had certain advantages to a stage-struck kid. It was near Broadway and the theatres, the big movie houses. It was also a place where a kid could pick up a couple of extra pennies if he was enterprising. Dick ran errands, delivered grocery packages and collected old soda-pop bottles for the one day in the week in which he lived—Saturday afternoon. Jingling ten hard-earned pennies in his pocket, he’d run down Tremont Avenue and escape into the movie house that promised the longest show—or Greer Garson. And there, for Dick, began his education.

“What other kids found in their homes, I learned from the actors I watched on the screen,” Dick says. “They taught me how to dress, a way to behave, how to talk and act. They helped me pick out the more valuable things in life, which without their influence I might never have sought or found. I spent hours listening to Ronald Colman speak, and I would try to improve my speech by copying his.

“I guess I could say movies gave me a sense of values, too. I was a kind of rebellious kid; I suppose being boarded out did it. I could have easily mimicked the older, tougher kids in the neighborhood. I would have, too, if it weren’t for the movies.

“And the film magazines helped me, too. I read Photoplay regularly, all about how the movie stars lived, the kinds of homes they had, their hobbies and sports, their problems and about their children and adopted children, I read how they reached the top. From these stories, I drew inspiration and a belief that I, too, had a chance. These actors I read about in the magazines gave me a form of selection, I guess you’d call it. They gave me ideals and a goal, which are the greatest things a kid could ask for: fairness, bravery, gentleness.

“I went through a stage when I loved Greer Garson. When I saw her in ‘Mrs. Miniver’ and in ‘Blossoms in the Dust’ she gave me an ideal of womanhood that is still vivid. I feel that when I marry I’ll know what I want, which will include a complete home of my own, something I’ve never had. One thing is certain; I’ll never marry an actress. I want a girl who is natural and simple without many drives. A girl who knows how to cook, who wants a home life, too. I want to be able to come home to my wife and my family at night. I’d like to have many children and I hope to be able to adopt a couple of kids, too. It’s tough being left parentless.

“I realize the insecurity I felt in my childhood is, in part, responsible for my wanting to act. I think, even as a youngster, I realized that through acting I hoped to find an identification—to be someone, who belonged someplace because of some one thing I could do well. And I wanted to give. When you have a family it’s easier to give, if you understand what I mean.” Dick suddenly stopped and looked anxious. “Like any normal kid, I had love to offer, a desire to please. I had few outlets for these pent-up feelings. In church, when I was an altar boy and a choirboy, I had a feeling of belonging. Summers, too, when Mom sent me up to my uncle’s farm in Connecticut. I worked on the farm and I was happy there. I remember one year when I was about eight my uncle let me name all the cows. I can still remember the thrill I got when I’d hear him calling the cows at milking time by the funny names I gave them. While there on the farm, I felt like I did in church. I belonged and, in little ways, I was giving. Acting, I thought, must be like this, for actors had given so much to me.”

Dick got a chance to act while in high school. Through the dramatic club of Christopher Columbus High he made his first professional appearance with the Chapel Theatre Group, which presented plays for children in New Jersey. (“When I was on that stage, I knew what I imagined was right. I felt an identification, a satisfaction.”)

Bitten by the acting bug for the remainder of that school term, Dick’s was a one-track mind. The only book he cracked was one on the Stanislavsky method; every spare moment went into dramatic activities—until the day he was notified he was in danger of flunking. “I finally made up the lost time, but my mother was instrumental in my finishing high school. I never would have made up the time and gotten my diploma if I had been left to my own devices.”

After high school, being of draft age, Dick joined the Navy and served aboard the USS Midway as an apprentice airman, spending a year at sea. Getting around the world added maturity, it also fostered self-doubts. “In the Navy, I went through a tremendous psychological bit,” Dick confided. “It was a tense period and, for the first time since I was six, I lost faith in myself. In a profession where so many are called and so few are chosen, how could you expect to be one of the few? I repeatedly asked myself.

“The Greek philosophers, Freud and Stanislavsky, all say, ‘Know thyself.’ I tried during that year at sea. At the end of the year, I knew the score: Common sense warned, Select a more secure occupation. Yet intuition said, If you’re so hep on giving something, give it. If you have to express it through acting, then act. The decision made, I still had one problem. Resolutions need money to be carried out.”

So Dick found himself a paying job as a switchboard operator and information clerk at the Willard Parker Hospital, a hospital for communicable diseases in New York (“It’s a city hospital,” Dick explains. “But with such a fancy name I thought when I applied for the job they’d never accept me.”) After five o’clock, Dick’s time and paycheck went to studying modern dance with Martha Graham and Erick Hawkins. A year and a half of dancing, though, convinced him that the dance was not his means of expression (“I had to talk, to say something, something inside”). He “let go” of dancing and signed up at the Herbert Berghof Dramatic Studio in New York, where by strange coincidence Jo Van Fleet, who plays his mother in “East of Eden,” was his first dramatic coach. For her and Anthony Mannino, another instructor at the Studio, Dick feels tremendous respect and gratitude. (“They helped me affirm what I’d always hoped—that I could be an actor.”)

After two years of study and supporting himself by working as a duplicating machine operator for Time magazine, Dick got an offer to appear at the Ann Arbor (Michigan) Art Theatre in the Round. He took it. The engagement lasted several months—then back to New York to a variety of odd, part-time jobs—messenger, filing clerk, switchboard operator—while he tried making that first big step up to, and behind, the footlights.

Dick’s opportunity came with “Miss Lulu Bett” at the Theatre De Lys in Greenwich Village in 1953, after nearly seven years of study. Agent Robert Lantz saw his performance and offered to sign him, and thus began Dick’s steady uphill climb through numerous dramatic roles on TV to “East of Eden.” All during this time, while acting, Dick continued to hold down part-time jobs. The summer of ’54 he was a soda jerk at Schrafft’s, the same counter, incidentally, where Kirk Douglas once worked.

When he tested for “Eden,” he worked at the Trans-Lux (“I didn’t take off my uniform until I had a Warners contract in hand and saw Mr. Kazan in person,” he says).

Knowing the background of Dick’s life, it seems paradoxical that he should play the beloved, respected Aron in “Eden,” instead of the unloved, rebellious Cal. Yet, this is the way Dick wanted it.

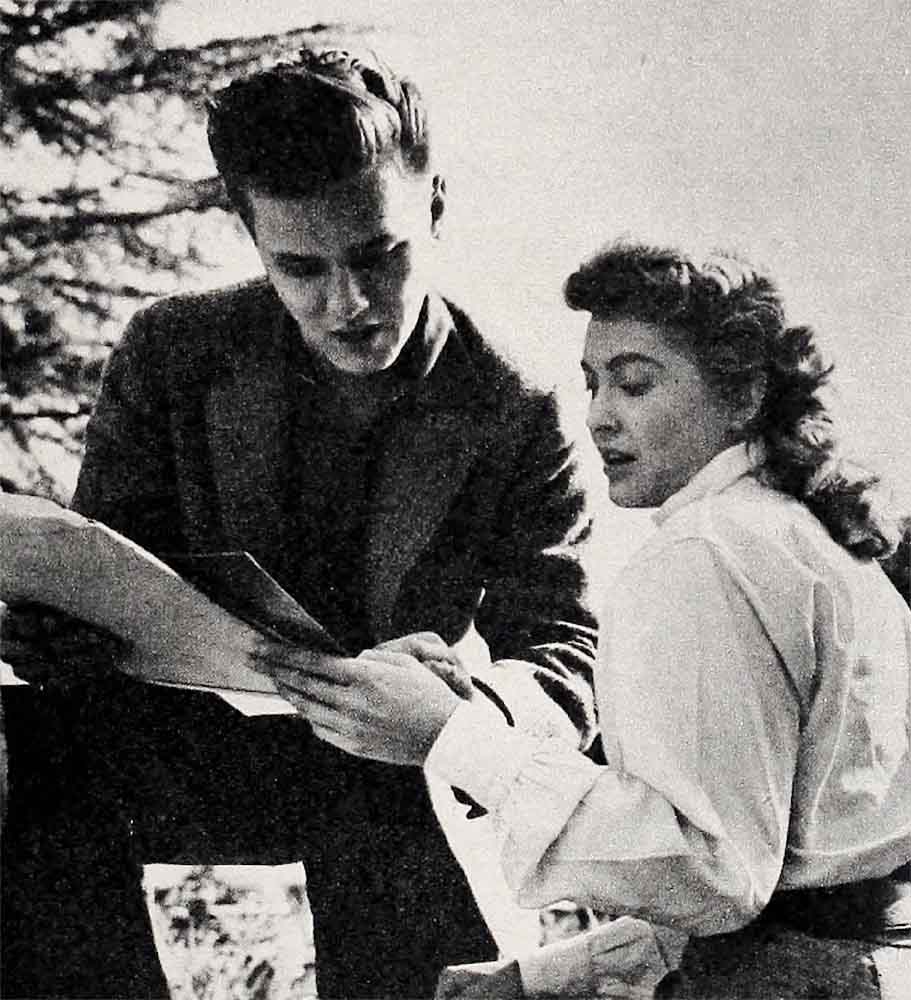

“I first read for the part James Dean plays, the part of Cal,” Dick explained. “But I’d read the book and all the time I was reading for Cal I kept thinking, I’m not Cal, I’m Aron. I could understand and feel my identification with Aron. I believe he did the best he knew how to adjust to the situation. I believe he really tried (as I have) in what he was searching for. When I got the opportunity to test for the part of Aron—I made the test with Dean—I tried to get this across in my reading. Mr. Kazan believed in me and I got the role.”

It’s a standard question to ask a new star what success and Hollywood mean to him. It isn’t necessary to ask Richard Davalos. Usually Dick’s smiles come half-reluctantly. He’s mostly serious with a trigger-fast sensitivity and a facility for holding his composure, but when he talks about Hollywood his reserve gives way to a smile that is contagiously enthusiastic

“Hollywood, I find, is pretty wonderful,” he candidly admits without any attempt to hide his emotions. “The studio has treated me fine, everybody’s been more than kind and considerate. The actors I work with have helped me enormously. Jimmy Dean and I roomed together for a while and I got to know him pretty well and to like him.

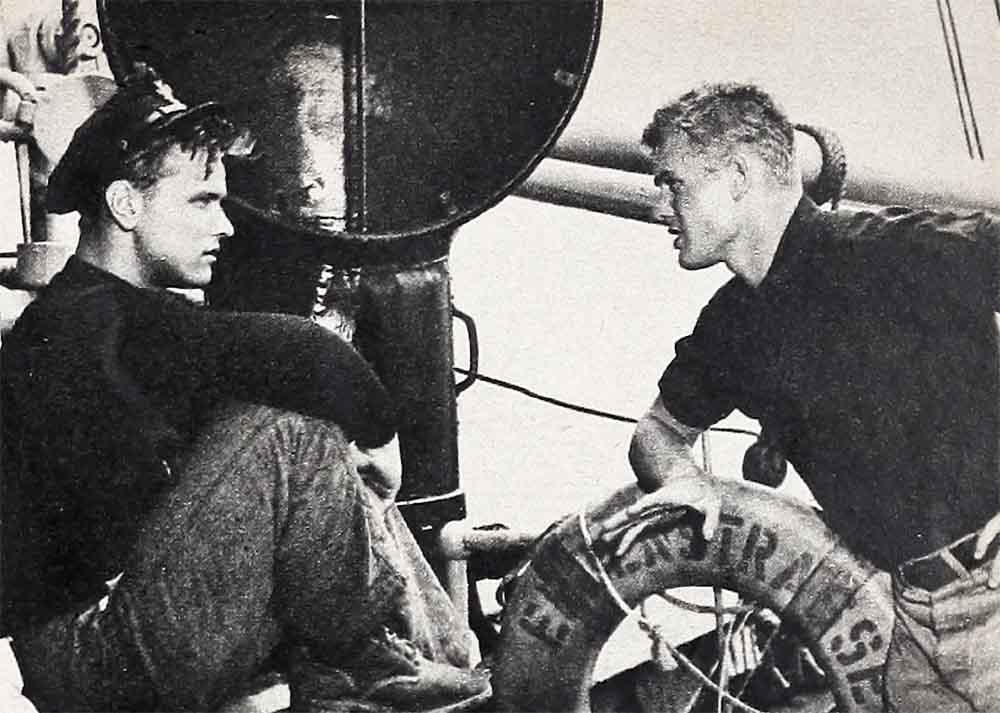

“Tab Hunter’s been swell, too. Tab and I both tested for ‘Battle Cry,’ but Tab got the part. Then, funny thing, after ‘Eden,’ I’m cast in ‘The Sea Chase.’ And who’s there with me? Tab! When we were on location in Honolulu, we stayed in the same house (remember Tab’s Hawaiian Diary, in the March Photoplay) and went on live TV shows together.

“It’s kind of interesting to go to a Hollywood party before your picture is released and nobody knows you,” Dick rambled on happily. “Kind of like asking for it, I’ve been told. But I didn’t find it that way. At ray first, and only, Hollywood party to date, I met Debbie Reynolds. She just sat down and started to talk to me. Certainly she didn’t know who I was and didn’t much care. Debbie’s great attraction is that she’s so alive. Lori Nelson’s another warm and friendly person.”

Dick finds the girls in Hollywood very nice, but so far he hasn’t done much dating. “I don’t have a car,” he explains. ‘I couldn’t even pick up a girl at her house and take her home. Besides, I like life simple—a movie with a cup of coffee and talk afterwards. Louise De Carlo, who had a small part in ‘Eden,’ is the only girl I’ve dated out here. We have simple dates.”

Even under cross-examination, Dick will never admit he’s been in love—“not what you’d call completely in love.” However, it’s rumored that twenty-four-year-old Mr. Davalos does have a special girl, back in New York, the girl he took to the New York premiere of “East of Eden.” But Dick, who shuns no questions regarding his career is adamant about discussing his personal life. “Let’s just say, this is a subject too close to me to discuss for publication,” he says firmly.

Has Hollywood changed his personal life? Not very much. He still lives in a boarding house, although he says that he and Perry Lopez, who was also in “Battle Cry” and showed him the Hollywood ropes and know-how, are thinking of renting a house together. He doesn’t plan to buy a car (“Can’t see spending that money. I can get to work by bus”). He still hasn’t bought himself a suit (“Rented my Tux for the premiere of ‘Eden’ ”). In fact,

Dick’s one personal extravagance as a result of fame has been a tweed jacket, which he speaks about with loving pride, happily shows its plaid lining.

“Perry Lopez sat in the store with me for nearly an how while I tried to decide whether I should spend the money on the jacket. We finally walked out without it, but a week later we went back. I put down the money and walked out with the jacket on.

“You know, when you’ve made a picture, two pictures, it’s assumed,” Dick said, “that you’re in the money. This is a big assumption. I still owe my school money. And I had a big dentist bill—I had to take care of my teeth. This was one thing that was long overdue. I’m not complaining, understand. Honestly, I’m so grateful I don’t know how to say it. I’m grateful to the people who fed me and gave me their old clothes, to the waiters in the cheap restaurants I patronized who gave me extra helpings, to the school treasurer who waited for the tuition money I couldn’t pay, to all the people who really didn’t know whether I was going to be a success but had faith in me, who raised my sights. Thanks to them, I have what I enjoy today.”

And what Richard Davalos has today is the assurance that the dream he so determinedly hung onto since he was six was a real one. “East of Eden” proves he can act. His is a success story, a dream with a happy ending. But for Dick the ending is just the beginning with many more exciting installments to come.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1955