Her Heart Is Gay

Ready,” the director said, “roll ’em,” and the picture “Our Hearts Were Young And Gay” began.

I stood watching just outside the fringe of lights, a funny little catch in my throat. The scene the director had elected to shoot first was to take place in the cabin of the ship on which Cornelia Otis Skinner and I had sailed to Europe in 1923. Passage in that cabin had cost us each eighty-three dollars, and looking at its replica now I thought we had been overcharged. The accommodations included narrow lower and upper white iron bunks, a folding washstand, a pair of water bottles, each suspended in a wooden ring. There was little else.

AUDIO BOOK

But standing in the center of the cabin, as the picture began, stood Emily, but this Emily was Diana Lynn. She was dressed in the duplicate of the tweed suit that other Emily had worn twenty years ago. The suit was of tweed with a fringed skirt and a long cape. The hat which matched it had been somehow faultily stitched, so that at the slightest provocation of breeze or toss of the head, the crown—and it was tweed too—would rise up from its folds to a clownish peak like a wind indicator on a landing field. But that Emily didn’t care whether the crown of her hat flew up, or her pocketbook fell down on the railroad track out of reach, or her safety pocket-belt which her mother had forced her to wear made a sinister looking bulge on her upper thigh. That Emily was young and gay; her heart was high and thumping with excitement. This was a dream come true. She and her best friend Cornelia were going to Europe together.

The very first words this new Emily said, when the director ordered “roll ’em,” were what that other Emily had said in that same cabin twenty years ago,

“Oh, Cornelia, I can’t believe it’s true. Emily Kimbrough is going to Europe!”

For one strange, timeless moment that Emily and this one fused. I was once more that girl in that same cabin on the ship about to set forth on the trip Cornelia and I had yearned for so long. And all of the adventure and beauty of Europe lay ahead of us. The things that had come since then to both of us were yet to be.

The director called, “Cut.” The scene ended, and I was twenty years older again. It had been a moment not apt to happen in one’s life, and never to be forgotten.

Diana Lynn had become Emily Kimbrough because Cornelia and I, after all these years, had written a book about that trip abroad, and called it “Our Hearts Were Young And Gay.” Paramount had bought the book, and this was the picture from it.

I was there because Paramount had invited Cornelia and me to help the producer, Sheridan Gibney, write the motion-picture version of the book., That was what we called it until Hollywood taught us to use the strangely medical term it employs for the transformation of a book to a picture—“treatment.” Then I had been asked to return to act as, what Hollywood calls, the technical adviser, for the making of the picture.

Diana Lynn was my youth restorative. So was Gail Russell, who was to play the part of Cornelia, but it was Diana after all who was Emily. That did make, naturally, a particular bond.

I had been working on the lot for nearly two weeks before I met her, but I had been there only a few hours when I first heard about her. The first day at lunch in the commissary the head waitress came over to take my order. Before I had time to preen myself on this special attention, she spoke.

“I came over, Miss Kimbrough, to tell you how pleased we all are at Dolly’s getting the part of Emily in your picture.”

I answered that I was delighted, too, but that I had not met her.

“Well,” the queen of the dining room continued, “when you do you’ll be as crazy about her as everyone here. I don’t think there’s anyone on the lot who has more friends than Dolly.”

“I’m terribly afraid,” I told her, “that there’s been a mistake. I understand that the girl who is to play Emily is named Diana, Diana Lynn.”

The queen of the dining room laughed.

“We’ve all known her so long,” she explained, “that we forget her new name. She’s Dolly to us, Dolly Loehr. They only changed her name recently to Diana Lynn, but to us she’s always Dolly. We all root for our favorites here, you know, but I don’t think there’s anybody who’s had as many people wanting her to get that part as Diana.”

Later that afternoon I went over to the gymnasium to see my old friend Jim Davies. He had worked over Cornelia and me during the winter before when we were trying to offset the ravages of delicious California food. Jim wasted very little time on renewing our acquaintance. He wanted, he said, to tell me how tickled they all were that Dolly was going to play the part of Emily.”

“She’s a great kid,” he assured me. “Deserves everything they give her. I bet there isn’t a person on this lot who doesn’t know her. She’s shy, but she likes everybody.”

That same day I saw Preston Sturges. He waved to me from across the garden which the Paramount buildings surround.

“I hear you’ve got my child Diana,” he called. “Everybody will tell you what a nice kid she is, and what a good trouper. Let me tell you, she’s an actress. You’re in luck to have her.”

This went on for nearly two weeks. Diana was away on a holiday. By the time she got back I had heard the refrain so often that I was apt, when someone approached me, to say immediately, “I think we’re lucky to have her, too.” Even when it turned out to be an invitation to me to go out to dinner.

Sometimes I think that when another human being is so highly and so constantly praised, the result is apt to be a slight antipathy set up in the mind of the hearer—or perhaps I am just that contrary. At any rate, I began to have a slight feeling of uneasiness. It wasn’t possible, I brooded darkly, that people who were as much liked as that could turn out to have much character.

Edith Head, who is the czarina of the Paramount costume department, telephoned me one morning.

“Diana is here,” she said, “for her first fitting. Could you come over?”

I went of course, but as I reached the door of Edith Head’s office I almost turned around and went away. I realized suddenly that I cared terribly about the girl who was going to play Emily. Not out of conceit, but out of a sort of homesickness for that other Emily, a kind of yearning to see her once more just as, for all her absurdities, she was. I opened the door, walked in and stood very still.

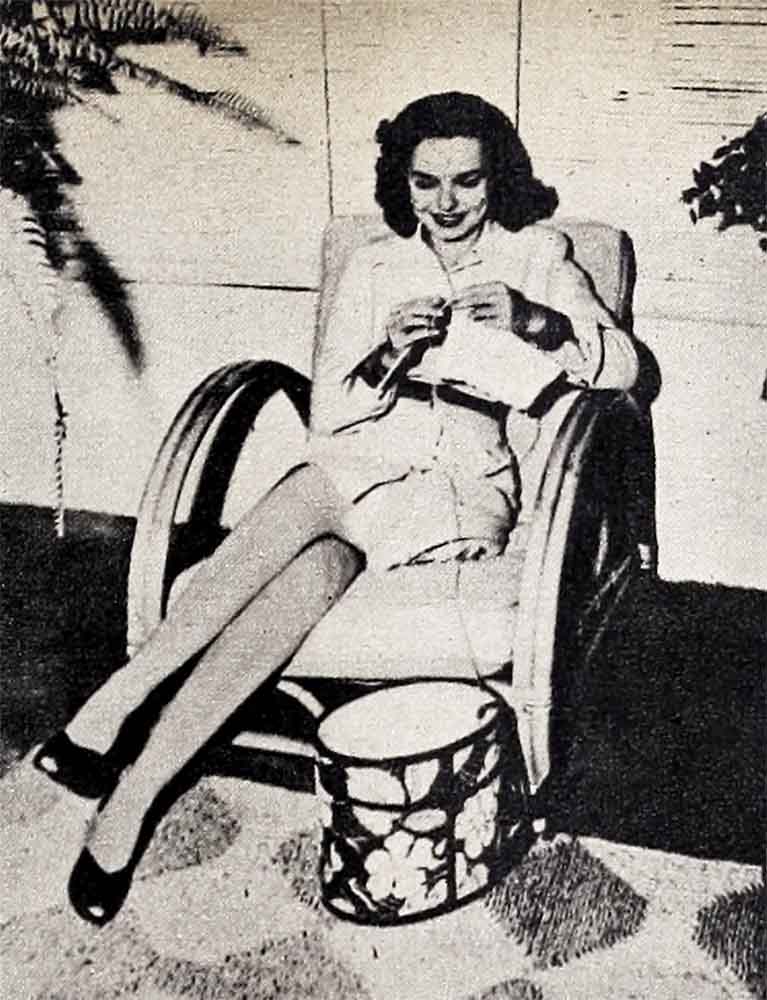

Diana was standing before the long mirror in the fitting room beyond Edith’s office.

Edith said, “Here is Miss Kimbrough, Diana.”

She turned around quickly, and came toward me. My first gasp was at her enchanting looks. It is not, I daresay, unusual to find that a young Hollywood star is pretty, but I had been thinking of her in terms of Emily, therefore I was surprised. And then in succeeding gasps came the realization of how young she was, really young, and how intelligent. You couldn’t have that broad forehead, those clear wide-apart eyes, very grave, a little anxious, without intelligence behind them. And what lovely manners—charm, too. We shook hands. There was no archness, no fluttering, no coyness, no gushing—just a very clear-eyed, straightforward, sober look.

And she said, “I want very much to do this part well, Miss Kimbrough. I’m working hard at it. Could we, do you think, talk it over from time to time when you’re not busy?”

When I was not busy—I whose days were spent drawing pictures of candy tongs and nail buffers for the property department! This was a star whose days were crammed with rehearsals, coaching, dress fittings, dancing lessons, photographs, publicity and interviews. But this star was a well-mannered, well-bred, charming young girl who asked an Emily who was twenty years older to give a little of her time to young Emily.

We did talk together frequently. A few days after this meeting, we were photographed together. As the camera was turned our way, the shy young girl Diana became the experienced, wise Hollywood expert.

“Don’t actually look at me, Miss Kimbrough,” she instructed me privately, “when they tell you to. Look just beyond, like this.” And she demonstrated. “It comes out much better.”

She gave me a few other instructions, which I tried stumblingly to follow. She was the expert. When the photographer had finished, she was a shy, earnest, young girl again.

I teased her about the duenna who was always at her heels—an elderly woman always a little out of breath and always with the look of one harassed almost to the snapping point.

“She’s my teacher,” Diana explained, “poor dear. I think she does get worn out, having to go everywhere I go.”

I found out that under the rules of child labor or the Motion Picture Guild—both, perhaps—anyone under the age of eighteen appearing in pictures must be accompanied at all times by a teacher or chaperone and must have so many hours of lessons a day.

I wish my children and their friends could have seen Diana and her duenna doing Latin, History, French while the hairdresser worked on a new hair-do for a trial photograph, or in the interval in a fitting, when a fitter went back to the workroom to sew a seam; while workmen altered a set, or electricians changed lights between “takes” of a scene. They might, seeing these schoolrooms, derive some inkling of what concentration can mean. Diana herself was troubled about her French. The duenna was not French. Therefore Diana was not sure she was acquiring the proper accent, though she felt that the groundwork was sound. She was going to engage a French woman to supplement the required work with actual conversation.

“I’d like,” she told me, “to be good at languages. I’ve always wanted to be.”

She was good enough at this time in music to have played with the Los Angeles Junior Symphony and for Stokowski. She had come, I learned, to Paramount by way of a piano, rounded up with some other child musicians for a picture, “There’s Magic In Music.” It is to Paramount’s credit, though undoubtedly a loss to the music world, that the studio snatched her from the piano stool and turned her in the direction of becoming an actress. And yet the young Lynn has had something to say for herself in the matter. Music was too deep a part of her life for her to cut it off so easily. There was no reason, she decided, why a career of a pianist should be entirely sacrificed for that of an actress. She was on her way to the concert stage. Therefore, she would consider each career only a temporary interruption to the other. In a pause between pictures this last winter she worked up a program and gave a recital, placing the highly commendatory reviews of that in juxtaposition to those of her acting triumphs.

It takes something more than talent to achieve either of those careers. It takes ambition and a greater than average capacity for work. Diana has both these, plus remarkable talent. I have a great respect, myself, for people who can and do work. I have, in consequence, a very deep respect for Diana Lynn. I have seen her stand in front of those mirrors in Edith Head’s dressing room and sway, unable to hold her balance, because she was so tired; but I have never seen her willing to admit it, nor forego any job to be done because of fatigue. I have seen other actresses blow up and go home because they were too tired to carry on. I had the greatest sympathy for them and wondered that they had been able to carry on as long as they had. I have never seen Diana give up and go home.

That rigidity of Standard might make a solemn, heavy and rather dull individual—what we used to call a greasy grind, back in those school days of “Our Hearts Were Young And Gay.” But you cannot estimate Diana if you forget her dimples nor would you be, on the other hand, aware of them were she not a gay, bubbling child. Her eyes actually do dance with laughter behind them.

When Joe Lefort, assistant director of the picture, went with me to the dance studio, it was for the purpose of showing the young members of the cast how to dance the Castle Walk, the Boston, the Hesitation, and the Maxixe. We enjoyed it enormously, Joe and I, swooping down in a long curve for the Boston, rising to what we considered a very pretty tip-toe for the Hesitation—rather fancying ourselves on the whole as something sophisticated and chic for these youngsters to see. That is, I fancied ourselves until the day when on a particularly swooping curve, I passed the eyes of Diana Lynn. The rest of her face was discreetly hidden behind the script of the play. She could not hide her eyes, because she had been instructed to watch us dance. No more could she hide the dancing taking place in them—a positive gavotte of merriment. I had no doubt then of her irrepressible sense of humor; I only wished that their inspiration might have been something other than me. I never again felt myself quite the replica of Adele Astaire.

The day I showed her how the crown of my hat blew up, and how Cornelia’s and my money belts bulged on our figures, or swung, she didn’t laugh. She was to make the scene in which those articles occurred hilariously funny. She was, accordingly, concerned with its technique. That is because she is an excellent actress, a comedienne of the first order, and she would as soon have thought of doubling up over a Bach fugue as of allowing herself to laugh over the preparation of a scene in a picture—however funny that scene was intended to be.

On the day when the scene concerning the swinging of the money belts was taken, men rocked the set rhythmically and constantly. They did this by means of superimposing the scenery on large rockers, and then by attaching ropes on either side. At a given signal the crew on one side hauled on the ropes and then the crew on the other. The result was a motion unmistakable to any of us who have gone as much as a hundred yards to sea. The result to both the girls was unmistakable, too. You could see it from the pale green cast that came over their make-up, and from the somewhat glassy look in Diana’s eyes. No one will ever make Diana believe that any part of that scene w as funny.

But she was such a good sport about it. Over and over she let them rock her, tottering back after nature had shown her what happened to seasick people, and trying the scene again. She will try anything again and again, if it’s part of her job. She may be dropping from fatigue, or seasickness, but she will not give up until the director says “cut.” Then she will be back on her job at seven the following day—and gay.

Her manners are those of a beautifully brought-up child. Her capacity for work and her ability to make it count are the qualities of a very intelligent and well-oriented adult.

It was quite an experience to meet that Emily Kimbrough. But, as the old woman said in the Mother Goose rhyme, “Lawk o’mercy, this is none of I.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1945

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments