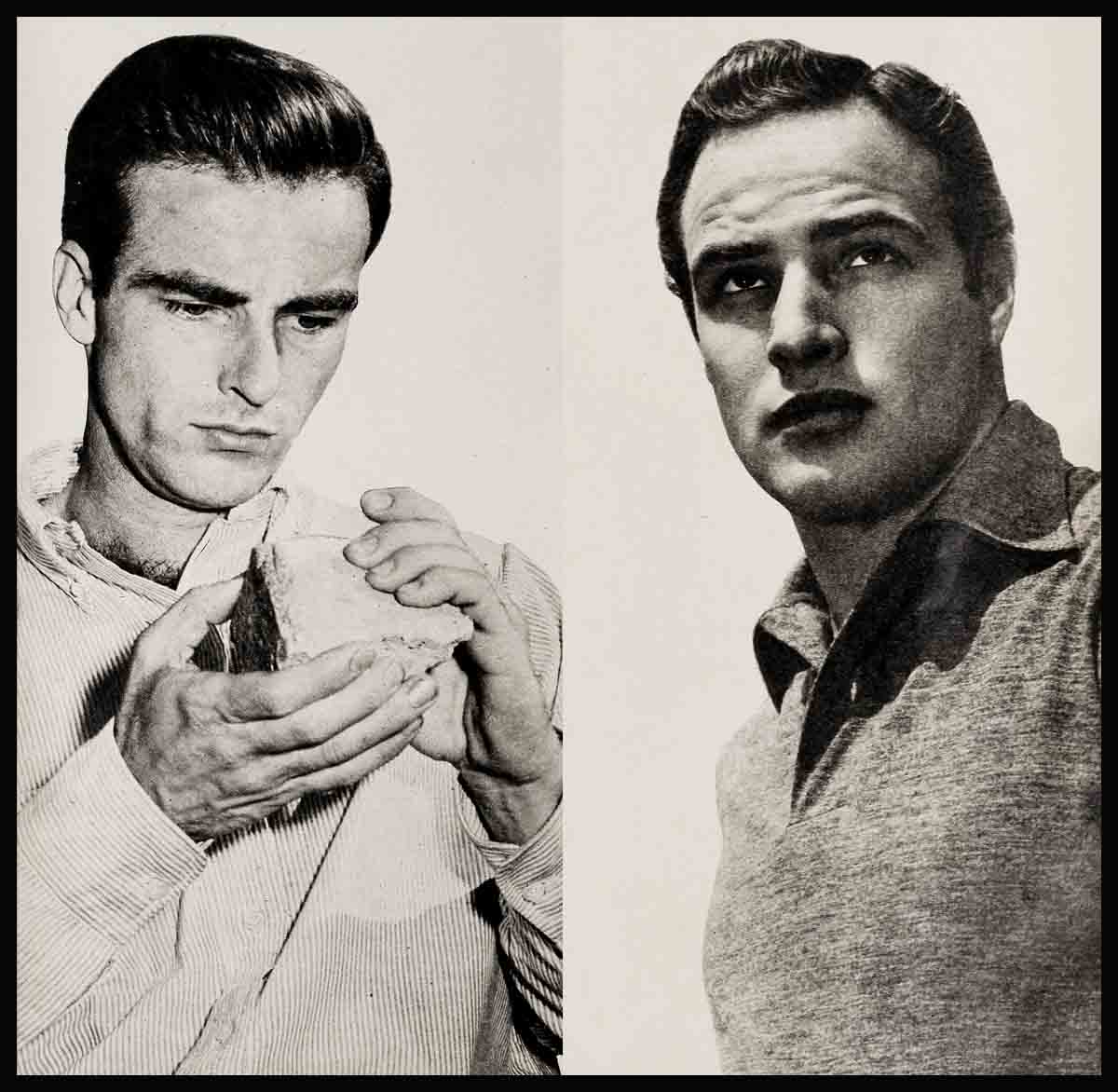

The Gold Dust Twins—Marlon Brando & Montgomery Clift

The words “movie star” used to mean fabulous ways of life, leopard-lined Rolls Royces and capital-G Glamor—but Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift have reduced the term to torn T-shirts and old tennis shoes. Are these two deglamorizing the film capital? Have they neglected their obligations to the fans who put them in the chips? Is their contempt for Hollywood fair, considering that Hollywood feeds them? Here is an unusually frank commentary written by a top reporter and presented just as we received it.

The Editor

Nicholas Schenck, the mogul behind the scenes at MGM, recently made one of his infrequent trips to Hollywood to see what was happening at his giant glamor factory, the studio. On the surface things appeared to be in order. The cameras were turning, the directors directing, the actors acting, the commissary was open and selling chicken soup. Dore Schary was in his office plotting new and better movies, and his underlings were still driving to work in Cadillacs every morning. But something was wrong, and Schenck was worried.

Nicholas Schenck’s first concern is revenue. He is the man who is directly responsible to the stockholders and he knew, on this trip, that a good many things had to be done to stimulate the nation’s interest in movies.

“We’re Icsing our touch,” Schenck is reported to have said at a closed meeting of top brass. “The whole world used to be interested in everything that went on here. We were the most glamorous city in the modern world. The name ‘Movie Star’ was a label that meant a fascinating, exciting man or woman, and it brought people into our theatres in packs, just to get a glimpse of the great stars in good pictures or bad. What has happened to that?”

Nicholas Schenck was speaking of the days when movie stars drove leopard skin-lined Rolls Royces and appeared in public swimming in rare furs or, in the case of the men, wearing capes and followed by a retinue of flunkeys. And while he was trying to make his point, one of the current stars, assigned to make a movie at his studio, was just reporting for work.

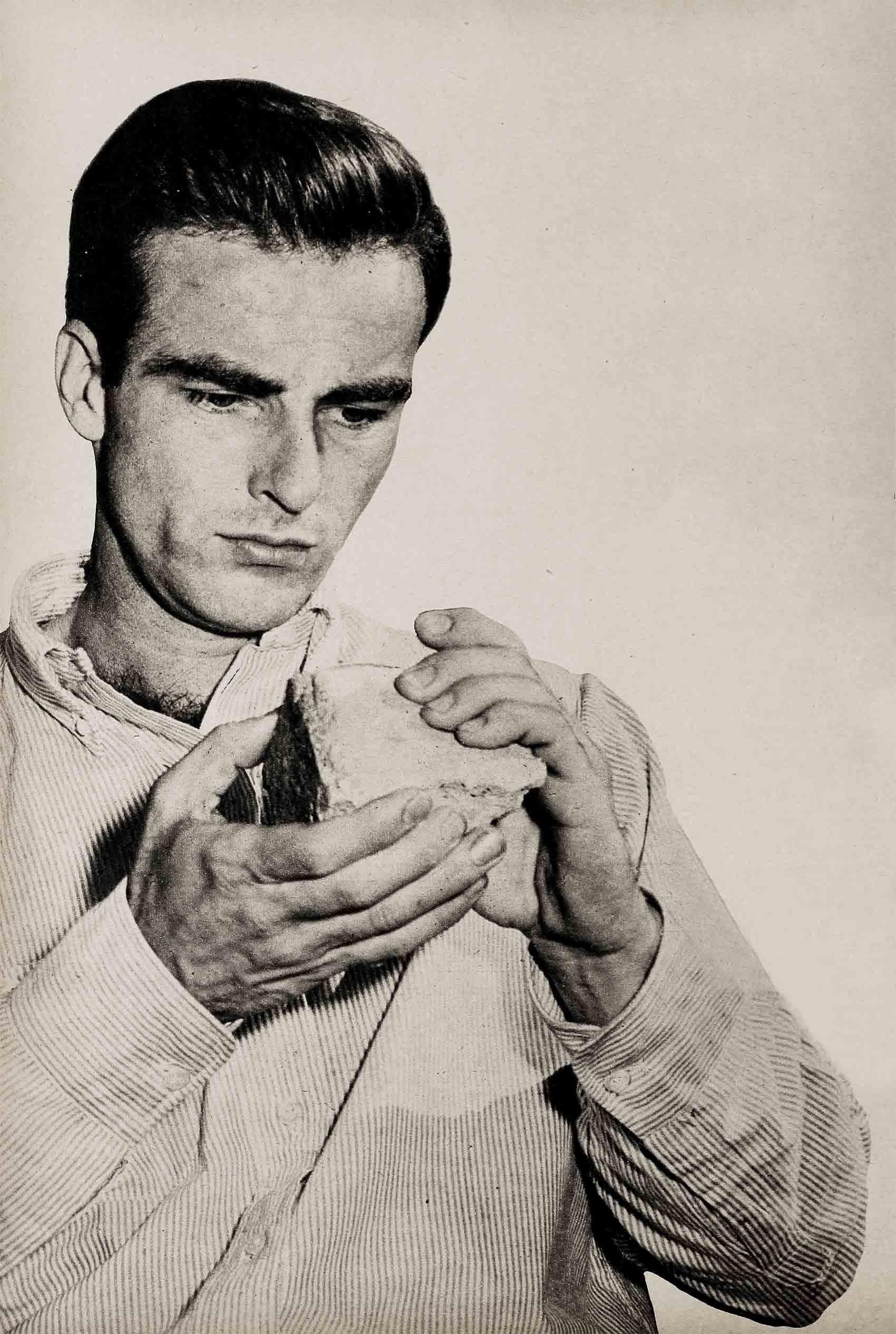

Well, to say the least, it wasn’t like it used to be. The man stepped through the front door of the studio wearing a pair of blue jeans and somebody else’s shirt rolled up at the sleeves and not entirely buttoned in front. His hair hadn’t been combed, at least not that day, and there was a stubble of beard on his chin. His shoes were unshined, and his manner was that of a laborer asking at the back gate for a day’s work. He was, however, greeted excitedly and ushered quickly into the swank office of the producer who was to make his film. His name was Marlon Brando.

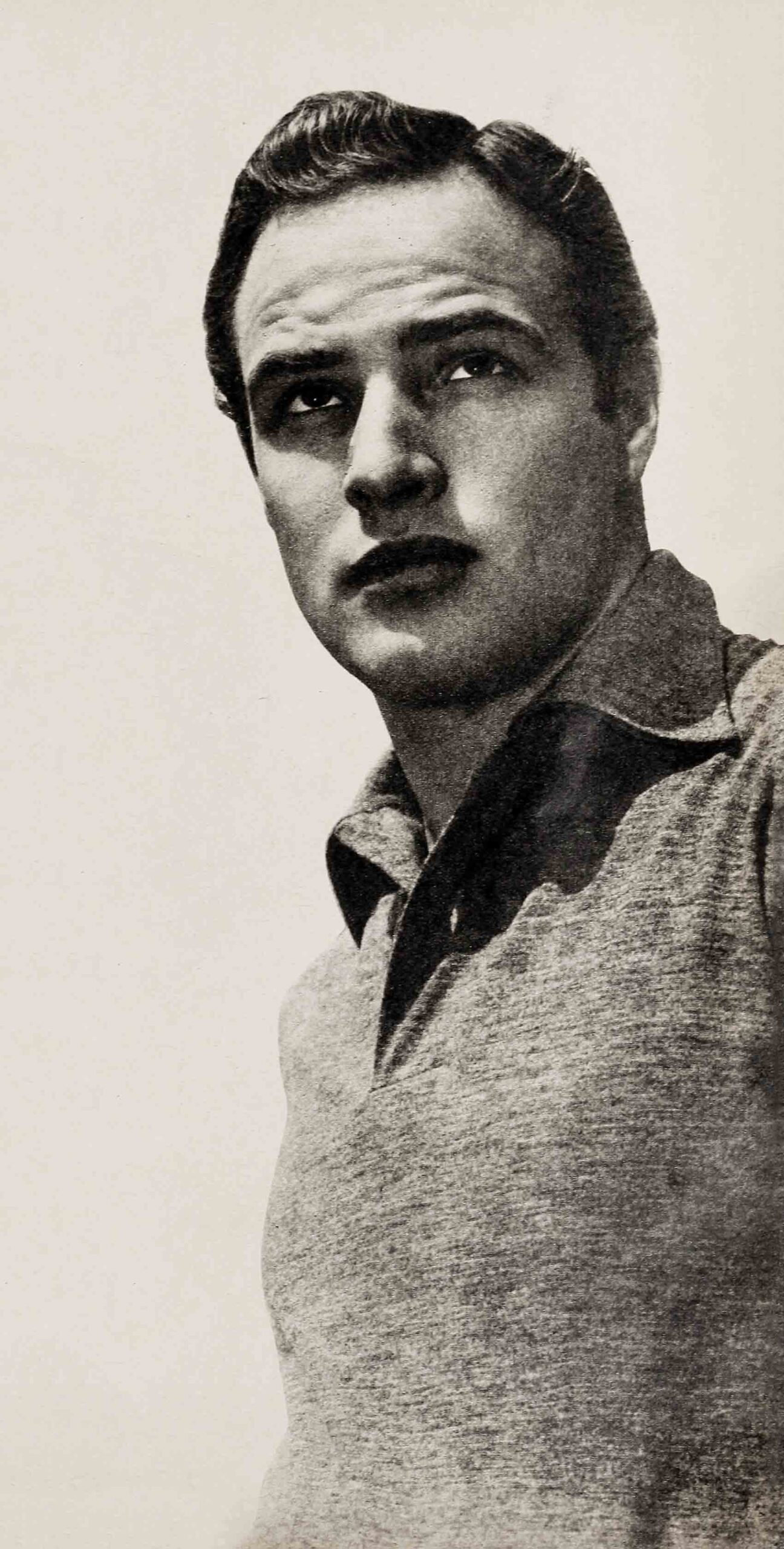

On the other side of town, at Warner Brothers, a tired publicity man was sitting at his desk holding his head in his hands. He was assigned to publicize an Alfred Hitchcock movie, I Confess, and he was looking into as bleak a future as a man in his position could imagine. On his desk was a list of phone calls from reporters and magazine writers who wanted to help him. All he had to do was produce the star of the picture. But the press agent couldn’t deliver, for his star, at that moment, was where he had been ever since he got into town. Dressed in old flannels and looking every inch like a mechanic off duty, he was sprawled out on a bed in a third rate apartment house, dozing. His name was Montgomery Clift.

Eccentricities of all sorts amuse most people, but the eccentricities of Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift have Hollywood in a turmoil because these two stars are taking away from the film capital some of the glamor that made it famous. There is no illusion on the screen when the theatre-goer knows very well that the man he is looking at in the fancy costume is, at home, a chap with manners and attire that might keep him from being invited into the average living room. And, apparently, there is nothing that can be done about it.

Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift, to give Hollywood its just due, are not Hollywood people. Neither one of them have starved on Hollywood Boulevard to get where they are. They never had to face hunger or the other trials that the usual aspirant in Hollywood does. They came sailing into the movies on the winds of Broadway success. And they came, and come, to Hollywood for only one reason, gold. They come a-mining for the dust whenever they need it and then skadoo. And both have stated publicly that they wouldn’t give two cents for the whole town. Both of them at the time of this writing have informed their studio bosses that they will not give interviews for fan magazines, nor will they take off their old clothes and pose, like movie stars, for the picture pages of these periodicals. It looks as though Hollywood and Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift are at a stalemate.

It has been charged time and again that Marlon and Monty are nothing more than free-thinking young men who refuse for basic reasons, known only to themselves, to conform to any movie star tradition but picking up the fat pay check. Their supporters claim that they are singular artists, too concerned with their mauling of the Muses to bother their heads about rational matters. And too steeped in the traditions of the theatre to care if anybody puts down a dollar out front to get a peek at their genius. This is nonsense.

One old-timer, a man who holds the deep respect of actors, and who in his prime lived the true life of a movie star, snorts when their names are mentioned and cries that in his day neither one of them could get work as an extra. This is terribly harsh, according to other old-timers who think Monty and Marlon certainly could have been extras but might never have got to the top of the heap in a time when competition for stardom was keener.

A careful check of the situation reveals that although Monty and Marlon have had rather celebrated careers both on the Main Stem in New York and in a few artistic-type pictures, neither one of them has distinguished himself at a box office to be worthy of the fabulous fees they exact for their movie efforts. True, Monty made Red River, a big money-maker, and A Place In The Sun, which made a nice buck, but the rest of his films have not been gold mines. Marlon made Warner Brothers happy with A Streetcar Named Desire, but none of his other films had bank tellers working overtime counting profits. And yet both boys demand salaries in excess of actors who have been making smash pictures for 20 years and more. A logical conclusion would be that the lads have found a strawberry patch they’re picking clean.

A wise movie man once said that the way to sell movies was to have the star put the print on his back and travel the land peddling it as he trudged. Marlon and Monty refuse to do this. They feel perfectly free to wind up shooting and take off for New York or Europe, leaving the Hollywood folk to sell the effort as best they can. The fact that some of these pictures have been what is known in the trade as “bombs” is an indication of faithlessness. It is not good enough that Marlon mumble into a moustache for a couple of months for a fortune, then dash off to study tinsmithing or something until he feels the urge for more gold; or that Monty sag through a movie between cat naps and then walk through a brick wall into nowhere until the uncertain producers raise his fee again.

The private lives of Marlon Brando and Monty Clift, are, to be sure, not average and are certainly not like a fan’s idea of a movie star. An astute observer once said that Marlon Brando has blue-jean skin, for that is all he ever seems to wear—at least in public appearances, and that the torn T-shirt he wore in A Streetcar Named Desire is swank compared to some of the things that hang in his clothes closet. The only time he has been seen in a suit, he confessed that it was his agent’s (his agent is a good 50 pounds lighter than our hero). Marlon’s idea of good all-weather headgear is a knitted seaman’s watch cap which, it is said, he showers in. One bitter winter long ago he lost his overcoat and has never bought another.

And this is the lad who is at present playing the romantic role of Mark Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

In the wardrobe department Monty Clift fares a little better. He wears a pair of pants and a jacket, but, his friends opine, it is only because his frame, undraped, is not a beautiful thing to behold. Monty never clipped the coupon that tells you how to have bulging muscles for a dollar a week. And, being a shy lad, he has no wish to display his physique. A member of the press who once got a peek into Monty’s closet found it bare of clothing. He asked if the actor was moving and was informed that Monty had his wardrobe on his back.

Having a date with an old-time movie star was something to watch. Something a movie fan, lucky enough to observe, would never forget. Flowers would arrive in the afternoon. And at the appointed hour the star would appear in a glittering car, driven by a handsome, aloof servant. The star would alight and, after being properly announced, kiss his date’s hand, lead her to his chariot and take her off to an evening of dancing, champagne and caviar.

This writer happens to have observed one of Marlon Brando’s dates. He arrived in mid-town Manhattan during the busy theatre hour aboard a dirty old motorcycle. His blue jeans and leather jacket were glistening this night, for it was raining, almost a cloudburst. He stood three floors below, his date’s window and howled, like a wolf after its mate, for the young lady to come down. When she did, he piled her onto the back seat of the motor bike and whirled her off to a sodden tour of Central Park. And they dined beside the reservoir on sandwiches he had made himself. The next night she went to a movie with a nice polite bus driver and had the time of her life. She is now one of the many who stay away from Marlon’s pictures. She is one of the disenchanted.

Monty’s dates are different only in that he is not the type to ride a motorcycle. A young lady he dated in New York stated that they went to a nice cozy saloon on Third Avenue. They sat in a back booth near the kitchen and ate a spiritless hash while Monty dozed between courses. After it was all over, she bracketed Monty Clift as a glamor boy somewhere between Butch Jenkins and the night clerk of a Bowery flop house.

An interview with a movie star in the good old days was quite an event. The star generally received in a lush palace filled with rich evidences of extravagance and an artistic soul. The star was dressed to the teeth in a cashmere suit. silk shirt and flowing fifty-dollar tie. Coffee in antique silver service was on the coffee table and spirits of rare supply were in cut glass bottles on the bar. The star never stepped out of character, so that when the interviewer left? he walked away with the impression that he had just shared a moment or two with Sir Launcelot.

This writer once had an interview with Marlon Brando. The actor appeared at his gate wearing a pair of shorts that looked as though they had been salvaged from a long forgotten YMCA and a terrifying multi-colored cap that must have at one time been owned by a lady bird watcher. He entered and, for the first two hours, said nothing more than “Can I take a shower?”—something he did and continued to do for the rest of the afternoon. Then he mentioned that he didn’t like Hollywood, was hungry and wished he were dead. It was about as inspiring an occasion as a visit to a juvenile detention home.

Monty Clift doesn’t get as many interviews as Marlon, only because he is harder to find. A reporter who once set out to find him to ask him if he planned to marry Elizabeth Taylor, stopped at the end of the third day because he began to feel like the detective in a Mickey Spillane novel. Even if you have a date with Monty Clift, one of his pursuers claims, you have to shadow him to the place of rendezvous.

It would be totally unfair to say that Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift give nothing to Hollywood. To the best of this writer’s knowledge they are not related to anyone in the moving picture business and must merit, in some manner, the money they pick up here. But it is an indictment against Hollywood that it has not discovered its own talent, which will assist in carrying on the grand illusions that sell movies and are so dear to the hearts of the young people who find in the magic of the cinema a few hours of enchantment each week.

It is very disconcerting to see a boy dressed in tatters standing before a group of highpriced showmen and telling them flatly he will take their money for acting but will not assist in selling the finished product to the public. It is unfair because the public is interested almost as much in the glamorous off-screen life of the stars it maintains as it is in their screen appearances. And the picture of Monty Clift lying in semi-slumber on a cot in a darkened room and informing his bosses, through an intermediary, that he will not be available for gab, except before a camera, is no less disheartening.

What is the solution? Apparently there is none. It appears that the die is cast. Monty Clift will remain Monty Clift and will not change, for it is the fancy of this younger generation of stars that they owe nothing more (for their riches) than their spell-binding performances. It is the fancy of Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando that they can live their lives as they wish as long as they are casually brilliant in their work before the cameras. They can hide in condemned tenements or snooze in caves, unwashed and unglamorous, as long as they display a talent on film.

Both Marlon Brando and Monty Clift have a beef with Hollywood and these beefs should be aired. Marlon’s is that pictures are sterile, made by sterile men, and that they do not allow him the actors’ thrill of getting an immediate, direct reaction from his audience. This has undoubtedly been responsible for his sullen behavior. But he has apparently not given a thought to the fact that the applause for a movie star comes after the lights have been turned off for the last time and the cameras have been stored in their lockers. The old timers could tell him, if he’d listen, that the cheers when they face their audiences on personal appearance tours and trips to far cities is as thrilling as anything that ever came across the footlights. It’s delayed, but it’s as great.

Monty Clift’s beef is almost the same, except that he feels Hollywood wishes to change him from a relaxed kid to a man with a zest for a medium he dislikes. His background does not entitle him to this, for before he came to the movies he was no earth-shaker in the theatre. It was likely that the talent of the man who made Red River put art into his screen acting. Monty, like Marlon, refuses to face the fact that no actor in the world is so magnificent that he can do in eight hours the work that warrants the huge sum of money paid him. While the salary of Monty is as much a secret as the wage paid Marlon, it would not be too far out of line to say that they have been paid $5,000 for an eight-hour day. And for that sum, they should be expected to peddle the film that winds up in the cans.

Although they are suspected geniuses, both Monty and Marlon could learn a lesson in ethics from some of the young, home-grown movie stars who made it the hard way. Tony Curtis is one. Bill Holden is another. Marilyn Monroe is another—and so is Dale Robertson. These are actors who are movie stars as well. They came here hungry, all of them, and what they have attained they have come by by the sweat of their brows and the hunger in their bellies. Their movies make money. And one of the reasons is that they work at being movie stars 24 hours a day. And when they are not making movies, you will generally find them out in the sticks, or in the neighborhoods of the big cities, selling the product, meeting the people who pay them face-to-face and never ducking down alleys to hide from the fans that hold their destinies in their hands with the coins in their pockets.

Yes, Monty Clift and Marlon Brando can be fairly dubbed The Gold Dust Twins. They came to Hollywood like confidence men, looking like stevedores and acting like collectors from a finance company who want their money without a lot of nonsense. They come to take their tokens of gold, and then they amble off to their little Fort Knox’s, sighing with relief and looking for all the world like a couple of urchins who have just successfully raided an apple orchard.

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

No Comments