All His Life . . .—Farley Granger

At fifteen, Farley knew what he wanted. At seventeen, after one fast week in a little theater, he didn’t find it too startling to be hired by Mr. Samuel Goldwyn.

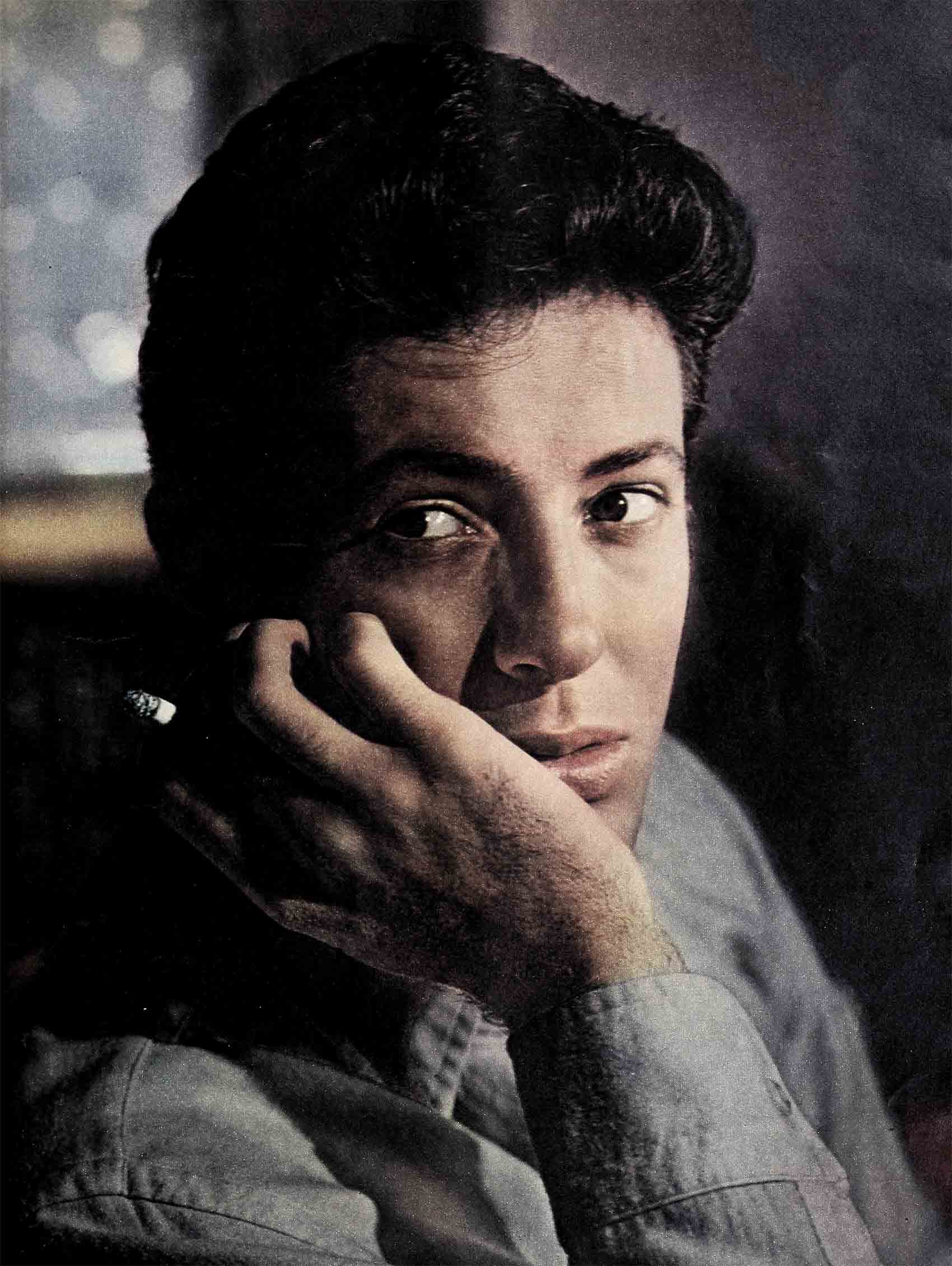

At twenty-four, he looks back and laughs at himself. He’s a mature twenty-four. Seven years ago, his eyes were full of stars. Eagerness welled like water from a natural spring. Now, he’s reserved with all but his intimates. Along the way, he’s shed a few illusions about people and things. Since they were illusions, he’s glad to be rid of them. He no longer sees life as a glorious succession of magnificent roles. Learning the hard art of compromise, he’s grown more realistic, though not more cynical. The enthusiasm’s still there, only it’s channeled.

Hedda Hopper made some predictions for 1950. “I think Monty Clift’s a great bet. I think Farley Granger’s better. He’s deeper and more sensitive. He’s landed a role that could make 1950 an Academy Award year for him, even at his age. In ‘Edge of Doom,’ he’ll play a man who accidentally kills a priest, then wrestles with his own soul. I’m putting my money on Farley to have the world at his feet when it’s over.”

“Edge of Doom” is finished. Together with “Side Street” and “Our Very Own,” it’s unreleased at this writing. Considering only those pictures seen by the public, you come up against a curious realization. Some have done well enough at the box office, some have won critical bravos, some have flopped. Run your eye down the list and, except for “North Star,” you won’t find an outstanding smash in the lot. Yet Granger’s stock rises higher and higher.

Allow so much for the fine Goldwyn hand on the reins. So much for the boy’s dark vivid good looks, and the pull of personality. On the screen he glows like a torch against darkness. But others have glowed before him, and since, and who knows or cares where their ashes lie scattered? Allow something for luck, which played its part, and that’s still not enough. Luck can give you a shove, but not to the top of the heap. When you hear the whole story, you get a sense of inevitability. If it hadn’t happened this way, it would have happened another.

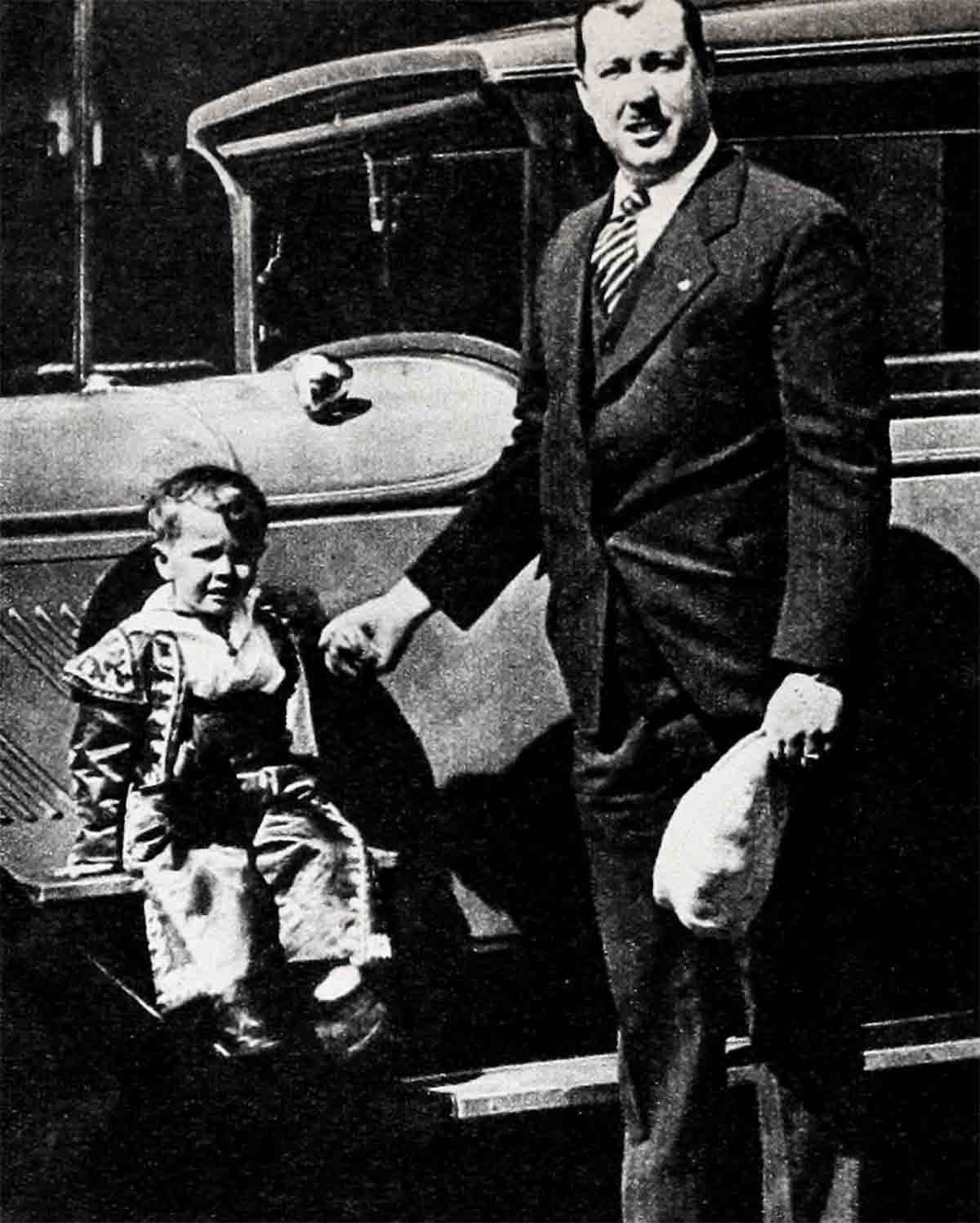

Farley’s first piece of luck lay in the nature of his parents. They neither spoiled their only child, nor tried to possess him. He was a third individual in the house, smaller, but just as free to express his opinions. They treated him as an equal, loved him without pressure and let him grow according to his bent.

Acting was his bent, though nobody paid it any mind except the kids whose fun he regularly ruined. Having gone with his mother to the movies Friday evening, he’d sally forth next morning and snag a pal or two.

“Saw the picture last night.”

“Yeah? Well, skip it, we’re goin’ today.”

“Okay, just this one little piece.”

In five minutes the gang had collected, and Farley’d be doing the whole thing up brown. Toward the end an anguished voice might yell, “Not how it comes out! Don’t tell us how it comes out!” The actor, lost in his art, didn’t even hear, and the audience was much too enthralled to break away. Not till the fade-out, did the muttering start. “Aw, what’s-a-use-a-goin’ to the movies now?” They went anyway, but the edge was off.

On the whole, however, their chum proved an asset. Weekdays, after school, they’d all clamber through the joints of some unfinished house. Grabbing slats for swords, they’d be transformed by the magic of childhood into pirates or the three musketeers in the picture last Saturday. If memory failed, Farley could invariably supply the cue. Moreover, he played the villain by choice. Heroes bored him. Heroes stood around looking good. And dumb. Villains ranted, hissed and met with a horrible fate. Farley’d take his horrible fate between his teeth, and chew on it to the last delicious shudder.

Today, he’s a better actor, but his views on heroes, or romantic juveniles, to give them their current name, remain unchanged. “They stand around in love scenes, they fight with the girl, they make up, they clinch. Nuts!”

Back in San José, Dad was an auto dealer, and a good one. There were no problems except, after Farley’d collected seven stray pups, Mother and Dad felt that an eighth might be superfluous. Even this wasn’t insuperable. Out with his father one afternoon, Farley met the sad eyes of a pooch who clearly needed a home. Dad was torn. “Tell you what, son. Maybe he belongs to someone who’ll come and find him. If he’s still around tomorrow, well, we’ll ask your mother.” Mother’s a softie. Next day No. 8 joined the private SPCA.

It was the depression that finally toppled Dad’s business. The Grangers reached a difficult decision: To leave the little town of their prosperous years and transplant themselves to Los Angeles, where maybe a man might find new opportunity. Farley’s only tears were for the dogs, and Mother understood exactly how he felt, having shed a couple of tears herself. “Farley, here’s a promise. I’ll plant myself at this phone and I won’t budge till every one of those dogs has a good home.”

“Won’t they miss me, though?”

“For awhile, yes. Then they’ll learn to be happy with their new friends.”

He thought it over. “Well, as long as they’re happy.”

The dogs were settled. So, presently, were the Grangers in a small house in the San Fernando Valley, a distinct advantage, from Farley’s viewpoint, over San José. Because Republic Studios were close by. He and his new pals sneaked through the studio’s back gate, and galloped imaginary steeds against real Western sets till somebody chased them out. This was high adventure.

Aware that money wasn’t too plentiful and feeling that he was old enough to help, he found after-school jobs and reflected on his future. Little by little came the consciousness of this flair for what he called “carrying on.” It crystallized and took shape during a high school course in public speaking. Having mulled things over by himself for awhile, he presented his findings to the folks.

“I’d like to be an actor.

“I’ve thought about it a lot,” he went on, “and this is for sure.”

“Fine!” said Dad. “Go ahead and try it. How d’you start?”

“I don’t know that either, but somehow I’ll find out.”

Actually, he was as green as his parents. Training was the thing, and he knew that some actors trained at dramatic schools. But for dramatic schools you need money. In the back of his mind buzzed the notion that maybe after graduation he could earn enough to see himself through. From lawn-mowing jobs he progressed to sacking. A sacker’s the guy in the grocery store who stands next to the cashier and puts stuff into bags. From fifteen he progressed to seventeen, resolution unwavering. He didn’t think in terms of movie cash or glamour. He just felt an inward sureness that acting was for him and, with the shining faith of his years, that somehow he’d get the chance to prove it.

“Wish we could send him to one of these dramatic schools,” Dad would say after Farley’d gone to bed.

“He’ll make it anyway,” said Mother.

Nevertheless, it was Dad who steered him toward the break. Dad was working at the Social Security Office, where actors came and went. One day, he talked to Harry Langdon. “I’ve got a kid who wants to act. Don’t know if he’s suited to it or not. What’s the best way to find out? Dramatic school?”

“Waste of time,” snapped Langdon. “Best thing is experience.”

“How does he get experience?”

“Little theater work. I’ve got a friend who’s casting a play right now. I’ll speak to him. Maybe there’ll be something.”

Langdon was as good as his word. A few nights later, Dad came home with the news. Farley was to present himself at such-and-such a place, where they were putting on a play called “The Wookey.” “Tell them you’re the boy Harry Langdon sent. They’ve got some parts open.”

“Gee, Dad, that’s swell!”

Mother had reached a tricky spot in her Argyle. She finished the row. “There! Didn’t I say right along he’d make it?”

Next day, Farley presented himself. They had him read a scene, then said, “All right, we can use you.” To keep the overhead down, they gave him not one part, but three, all small. In the wings, he felt nervous. On stage, he felt buoyant and self-possessed. “The Wookey” ran for a week. Mother and Dad, without prejudice, concluded that Farley was the best thing in it.

Maybe he was. Because, one night, a really unprejudiced observer came backstage and introduced himself. “I’m Bob McIntyre, casting director for Samuel Goldwyn. Like to have you come over to the studio tomorrow.”

Farley’s state of mind is a little hard to describe. He was elated, of course, and at the same time, calm. Never having battered his head against casting directors, it didn’t occur to him that what had just taken place was slightly spectacular. He’d known for two years, and much longer, subconsciously, that acting was his meat. This was what he’d planned on, now it was happening. Simple.

Neither was he overpowered in Mr. Goldwyn’s office next day. Bob McIntyre was there. So were Lillian Hellman and Lewis Milestone, writer and director respectively of “North Star.” Mr. Goldwyn looked him over, fingers drumming. “Hm. Physically, he’s okay.” Farley waited. “How many pictures have you made?”

“None.”

“Ever work on Broadway?”

“No?”

“How many plays out here?”

“This is the first.”

A sense of discomfort edged its way under his collar. He knew he was giving all the wrong answers, but what point in lying?

“Let’s have him read.”

Briefly, Milestone outlined the scene. Cued by the director, Farley read. Into the silence that followed, Goldwyn dropped eight little words. “Thank you very much. We’ll let you know.”

This is the traditional brush-off. Those words have fallen like lead on the hearts of hundreds of experienced actors. Farley was an innocent. He described the proceedings in detail to Mother and Dad. “Then Mr. Goldwyn said, ‘Thank you very much. We’ll let you know.’ ”

“Then what?”

“That’s all. Obviously, it means they’re going to test me for the part.”

In those days, Farley didn’t read the Hollywood Reporter. He therefore remained ignorant of the fact that Goldwyn had gone east in search of a boy. Three weeks went by. Farley couldn’t understand why they were taking so long, but doubt never touched him. Only once was he worried. At football practice, he fell, took a kick in the throat and lost his voice for two days. Which threw him into a fever. Any minute they’d call, and he wouldn’t be able to talk. Each time the phone rang and it wasn’t the studio, he’d relax.

In the end, his call came. Goldwyn had seen many boys, none of them right. Only one kid had looked the part, the kid from “The Wookey.” His was a face you didn’t soon forget. Goldwyn hadn’t forgotten his reading either. First quality ham. And yet, there’d been a spark.

He picked up his phone. “Get hold of the Granger boy. I want a test.”

They made the test on Friday. Saturday morning Mother went marketing. “You stick around, son, in case they call.”

Twenty minutes later, in the heart of the shopping center, she ran smack into him. “What on earth are you doing here?”

“Buying you a valentine.”

“But suppose they call?”

“They did. Said to come back Monday.”

Of course it was in the bag. On Friday nobody’d known him. On Monday, he walked through a maze of mysterious smiles.

“How was the test?” asked Farley.

“You’ll have to talk to Mr. Goldwyn.”

At 2 came the summons, and at 2:05 the magic words: “We liked the test. We want to sign you to a contract.” Since he was still under age, Mother and Dad had to sign for him. To settle their nerves, and in honor of his new boss, Farley took them to see a Goldwyn movie.

Most of you will remember how the Granger personality socked itself across in “North Star.” On the strength of this single performance, Darryl Zanuck borrowed him for the duration and beyond.

As an Army man himself, Dad can’t understand to this day why his son joined the Navy. Neither can Farley, except that he went down with a bunch of kids whose watchword was, “The Navy! They always give you a bed.” Plucked in the bloom of his career, Farley felt pretty sorry for himself. Till he started rubbing elbows with a lot of other fellows. Some had been in it two and three years already. Some had left wives and kids behind. Some had no jobs to go back to. Some didn’t live to get back to their jobs. He stopped feeling sorry for himself and began to grow up.

V-E Day was followed by V-J Day. As far as his mother was concerned, the war ended one bright morning in ’46 when the phone rang in the little Valley house. “Hi, Mom, we’re just in from Hawaii. Ill be home tonight. How’s about spaghetti and meatballs for dinner?”

They sat up till four, and by ten Farley was on his way to the studio. Having reached the reasonable age of twenty, he didn’t expect to be put right back to work. He was prepared to wait a couple of weeks, maybe as long as a month.

“Take it easy,” Mr. Goldwyn said. ‘Fool around. Play tennis. Sleep. You’ve got a holiday coming.”

“I feel fine. I just want to work.”

“You’ll work. Have patience.”

The months lengthened to a year. This was when Farley learned that plums don’t drop into your mouth just because it’s open. He chafed and pawed the earth, and Goldwyn patted his restive steed on the shoulder. “You’re too old for kid parts and too young for juvenile leads. We’re paying you to grow up. Just be patient.”

“I want to work. I’m wasting time.”

“You can wait, Farley. At twenty, you’ve got plenty of time to wait.”

Cathy O’Donnell, also under contract to Goldwyn, was waiting, too. To keep their hands in, she and Farley met almost daily at the studio and did scenes from plays. Then, through mutual friends, he met Nick Ray. They talked a couple of times. You couldn’t talk to Farley more than five minutes without tapping the well of his thirst to get going. So when Nick called and asked, “Do you want to work?” he laughed out loud. It sounded like a gag.

“Yes, I want to work.”

“Well, I’m sending over a script. Let me know if you like it.”

He more than liked it. So did Mr. Goldwyn.

“Fine,” said Nick. “Is there anyone special you’d like to make the test with?”

“Yes. Cathy O’Donnell. We’ve worked together a lot at the studio, we feel comfortable together.”

So Cathy played in the test, and Nick hired them both for “They Live by Night.” (In parentheses, we’d like to add that this is one of the best pictures ever to come out of Hollywood. It rated and got rave notices. For reasons we’ll never understand, the public turned a lukewarm shoulder.)

The day after its completion, Farley lit out for his first visit to New York. Bewitched by the city, he stayed two months. What brought him back was a call from Alfred Hitchcock, who’d seen “They Live by Night” and wanted him for “Rope.”

The career was beginning to look up. Meantime, he’d taken the logical step of moving from his parents’ home to a place of his own. Mother exacted just one promise. “I won’t have anyone shrinking my Argyles. You bring those Argyles back here to be washed.”

Since “Rope,” he’s grown old enough to be starred in romantic parts in “Enchantment,” “Roseanna McCoy” and “Our Very Own.” As noted, he still prefers character parts and makes no bones about saying so, to his boss or anyone else. They agree on most points. In spite of his yen for character roles, Farley realizes that you need a change of pace. In spite of “Our Very Own,” Goldwyn realizes that his boy has a feeling for drama, which is lost on straight parts. That’s why he bought “Edge of Doom.”

“Edge of Doom” deals with highly controversial matter. Goldwyn was well aware of this when he snatched it from under the eager paws of other producers. Farley knew nothing about it till his eye fell on a press release. “Story of a youth who kills a priest, bought by Goldwyn for Farley Granger.”

He made tracks for the studio.

“I expected you,” said Goldwyn.

“Where can I get hold of the book?”

“You can’t. It’s not in print yet. I bought it from galleys. There’s only one set, and the writers need it.”

For the next few weeks he made a howling nuisance of himself. No one who’d so much as touched the galleys was safe from him. “It’s great, kid, great,” they’d tell him soothingly. “Excuse me, there’s a man I’ve gotta see about a script.”

The books finally came. Farley took his copy home one afternoon and finished it before dinner. Part of him felt as if he were fresh out of a wringer, part like a soaring blimp. He called Mr. Goldwyn, his folks . . . and Shelley Winters.

Now that it’s over, he doesn’t like to talk about it much. He’ll tell you it’s the most exciting picture he’s worked on. He’ll tell you that Mark Robson, as human being and director, can’t be topped. Then he’ll change the subject. For the same reasons that send him out of town when a picture’s finished.

“In New York, the atmosphere’s different. My friends there are interested in what I’ve done, as they’d be interested in the doings of any friend. They’ll ask how the picture went, I’ll tell them, they’ll say, ‘Fine,’ and that’s the end of it. Here the view’s more restricted, and I’m not panning Hollywood. It can happen to a lawyer or farmer or mathematician who sticks too close to his own particular niche. This is my niche. I like it. I started out to be a good actor. Acting’s my profession, and I’d like to be a credit to it.

“But I no longer think it’s the be-all and end-all of existence. Other niches are just as important to other people. Things go on that are more important to all of us. Like the situation between nations. Like the talk about hydrogen bombs and the end of the world. People are so scared of dying, they forget about living. It’s got to be stopped. How? I don’t know how. If I did, I’d stop it. But I’d rather go where the questions are being asked than sit here and read the film trade papers.”

Paintings have always stirred his imagination, and in a purely minor way he’s started collecting. He has no artistic patter, but an intense curiosity about other people, other places and cultures. Breughel, with his rich earthiness and great love for the peasants, is one of his favorites. Standing in front of a Breughel, he’s carried back through the force of another man’s genius to a distant day and the other man’s feeling for his times. Any good artist produces a similar reaction. You can’t compare Toulouse-Lautrec with Breughel. Yet the Frenchman’s decadent images of the seamy side of Parisian life are just as revealing. “Imagination,” says Farley, “is the gift of children. You lose it as you grow older. But through pictures and music and books, you can try to restore it.”

His next picture will. probably be “Billion Dollar Baby.” Goldwyn wants to give him a chance at comedy, his feeling for which has yet to come across. Then again he’s looking forward to “Earth and High Heaven,” Mark Robson directing. Farley can hardly wait. With him, it’s a case of all this, and Robson too.

On the other hand, he’s against too much of Granger. Here, too, he and his boss see eye-to-eye. They don’t believe in foisting him on the public. Some producers, when an actor hits, seem to feel he’s going to drop dead next year, so let’s make all the dough we can while he lasts. Goldwyn would rather have people asking for more, than groaning, “Look, here’s that Granger guy again.”

Between pictures, life has plenty to offer. Farley’d like to do a play, when, as and if the opportunity offers. His first bow on any stage since “The Wookey” came during a personal appearance tour for “Roseanna McCoy.” There were six shows a day, and no written script. His job was to ad lib with the emcee. The prospect paralyzed him. But once he’d run through the deal a couple of times, you couldn’t drag him offstage.

He’s crazy to travel and anxious to settle down. Which isn’t as large a paradox as it sounds. Settling down means buying a house. At the moment he lives in a very pleasant apartment, for which he pays rent. Since it seems more sensible to pay rent to yourself than a landlord, he’s looking for a house.

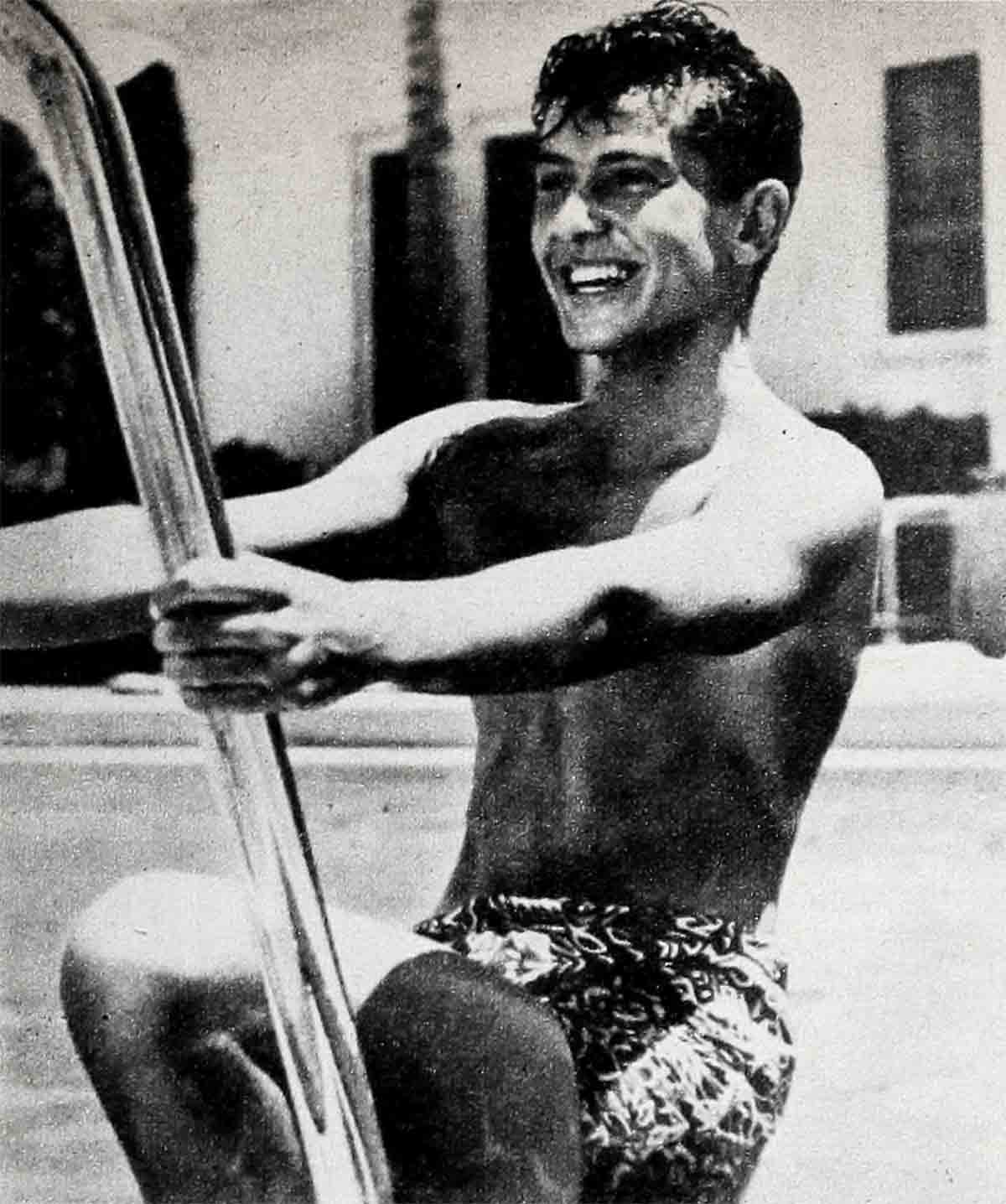

What he’d really like would be to move the Pacific a few miles east, and set it at his doorstep, to swim in, to walk in, to watch, to hear the surf boom at night, the most restful sound in the world to Farley. Since this isn’t feasible and the beach is too far away, he’ll compromise on a house with a view somewhere above Sunset Strip.

His tastes are simple. He drives a Chevvy convertible. Twice a week, his maid comes in to clean and prepare an occasional dinner, should the need arise. Mostly he eats out, a couple of times a week at his parents’, when he’s not working. “How’d you like to feed two starving gents? Okay, I’m coming over with Soand-so.” Needless to say, this doesn’t hurt Mother’s feelings. She’s the kind who can dish up inspired meals without turning a hair.

He can and does fix his own breakfast, and a sandwich for lunch if he’s fooling round the house. This latter activity consists in reading or playing records. In both departments, his library’s well stocked. His record collection leans heavily toward the moderns, but here, too, he’s beginning to restore the balance. Most people work their way from the three B’s to Copland and Hindemith. Farley did it the other way round. Stirred in boyhood by the new men who speak for the age we all live in, he’s now turning to the old. The first classic album he bought was Brahms’ “Violin Concerto.”

His sports are tennis and anything in the water. Summers he goes down to Balboa to sail. There was a time when he looked on dressing up as a form of torture. But he learned in New York that a man could wear a tie without choking to death. He’s a pushover for colorful sports shirts and jackets. Blue jeans are out, however, except round the house, and he draws a line between the casual and the sloppy.

There are few people he’s close to. Those few he doesn’t tire of, nor they of him. For a year he’s been dating Shelley Winters most. They have dinner somewhere, sit around and talk, take in a movie. Or they’ll go to Saul Chaplin’s for an evening of music. Or Judy Holliday will call. “Come on over, we’re going to play ‘The Game’.” “The Game,” otherwise known as “Indications,” still flourishes in Hollywood. Judy’s mad about it. Farley used to fight shy of it. But it grew on him, and now he’s in there making faces with the best.

The combination of Shelley and Farley presents something of a puzzle to outsiders who know neither very well. “They’re such opposites. She’s an extrovert; he keeps himself to himself. She’s for parties, he doesn’t care for them much.”

They’re not as opposite as all that. It’s true that Shelley’s more of an extrovert. But Farley’s no introvert, except with strangers. It’s true she likes parties better. Or rather, more consistently. Farley enjoys them in spurts. But these are surface matters. Basically, they have much in common. They laugh at the same things. They consider the same things important and unimportant. He understands her drive, because he has it himself. If he’s more relaxed, it’s because he’s been luckier. Shelley’s had to fight much harder for her career.

He feels great respect for her as an actress, and values her professional judgment. They read each other’s scripts and talk endlessly about their work. What he values most are her kindness and warmth of heart.

Are they going steady?

“Semi-steady,” he’ll tell you. “We’re very good friends.”

Comes the next cautious question. Could it turn out to be something more than good friendship?

He gives you a grin. Half-amused, half-embarrassed, wholly uncommunicative.

“I don’t know,” says Farley. Period.

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1950

No Comments