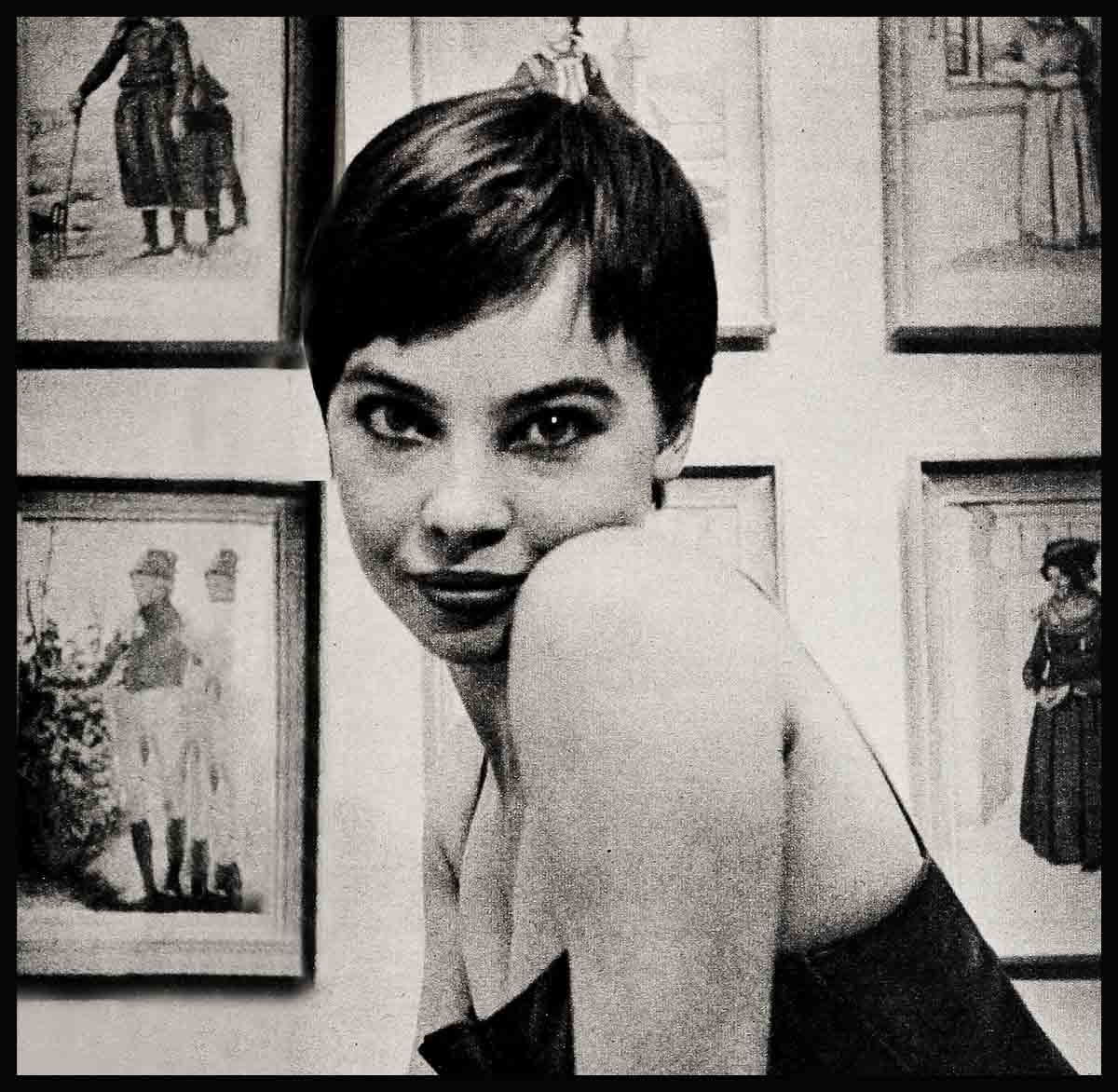

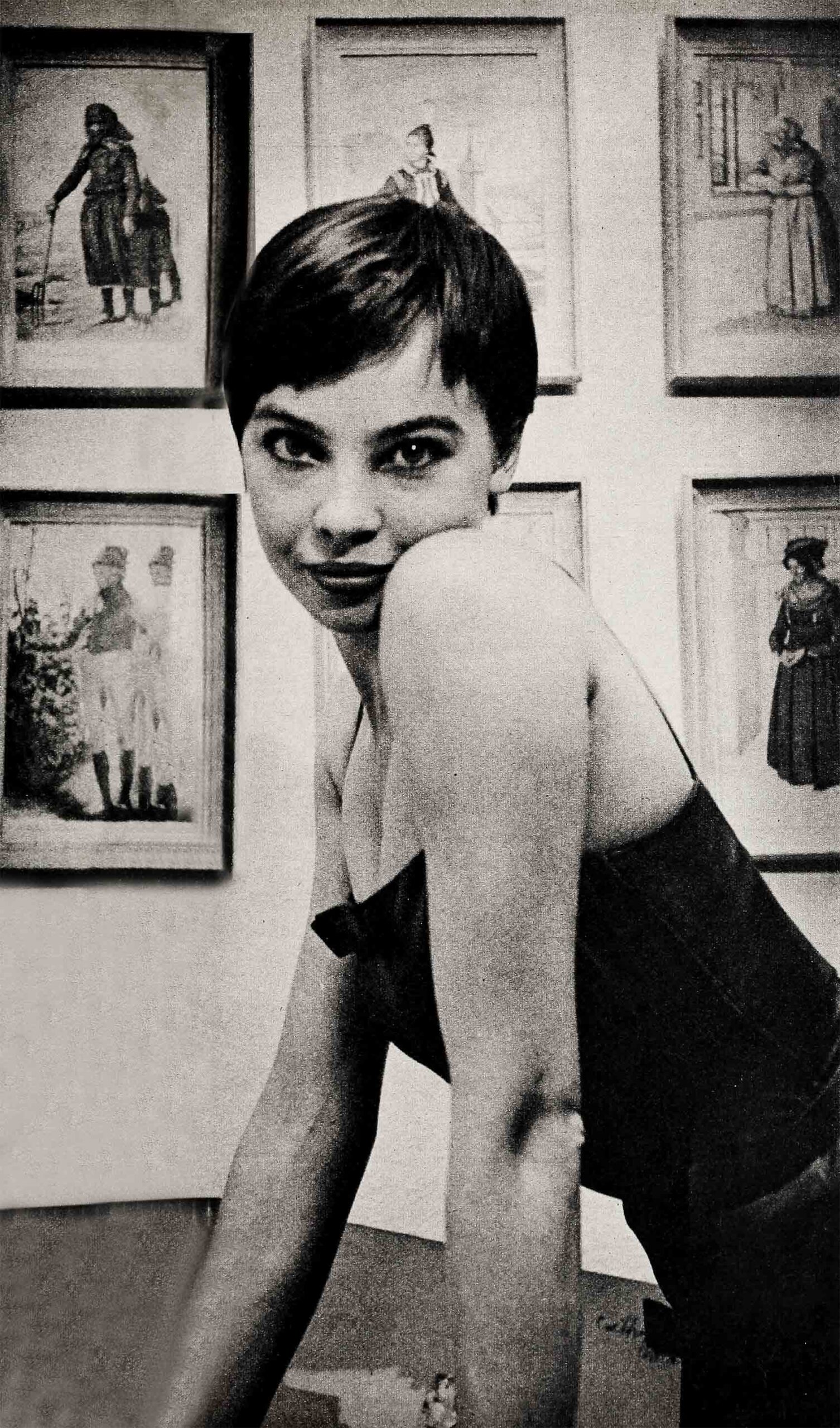

Unlucky At Love—Leslie Caron

For the third time, Leslie Caron has lost at love.

At twenty-three she has been through a broken marriage and two subsequent, serious romances, each of which ended with Leslie’s man marrying another girl. At twenty-three the sparkling, open, joyous child has become moody, unapproachable, absorbed only in her work. At twenty-three she is unloved and unloving. Why?

The unwitting villain of the piece—his motives perfectly innocent—was undoubtedly Geordie Hormel. He met her when Leslie was new to Hollywood and fame, new, in fact, to the world. He seemed then to represent the dream of every young girl—and most particularly of every French girl, brought up to believe in marriage and family life as the ultimate joy of life.

Geordie proposed on the second date. Leslie was swept off her feet with comparative ease. They were at the beach at the time, the night after they met. “Let’s get married,” Geordie said. “You must be crazy,” Leslie remarked. “No,” Geordie said. “I’m not crazy. I’m in love.”

Leslie was in her teens. Geordie was charming, wealthy, very personable. The proposal had all the romance of love-at-first-sight. He took Leslie home to meet his parents, remarkably fine people. She knew he wasn’t just talking—he meant it. The next thing she knew, they were in Las Vegas, getting married. But she didn’t know Geordie. There hadn’t been time for that. Leslie had always glowed and at first marriage increased her aura of happiness. “To be married,” she told reporters ecstatically after her honeymoon, “is the most wonderful thing for a girl!

“My career? What is my career compared to marriage? Geordie is now the most important thing in my life. He will be the father of my children. Oh, we want so many, eight, ten, twelve. Remember I am French, and French women like large families.

“Why, if Geordie asked it, I would give up my career. If he says, ‘We go to Minnesota,’ then we go to Minnesota. Geordie is my husband. I follow his direction.”

But Geordie’s direction led up a blind alley, and Leslie walked straight into tragedy. When misery came, she was unprepared to meet it. Nothing in her past had taught her what to do when her dreams disappeared, and when she and Geordie lost touch, she was lost, utterly bewildered.

So when she and Geordie knew they were through, decided to separate, see other people, Leslie did the only thing she could. She fled. She went home to the only two things she still loved and trusted—France and her career. She re-joined Roland Petit’s Ballets de Paris. Perhaps it was just a simple matter of being on the rebound. Perhaps it was because, the world of domesticity having let her down, she deliberately chose the least domestic man around. Perhaps it was because life just wasn’t complete without a love. Whatever the reason, last year Leslie fell very much in love with Roland Petit.

She had known him for years. It was he who had given her a start when she was fifteen, a Paris kid who wanted to dance more than anything else in the world. Now he gave her stardom as a ballerina, choreographing a ballet just for her. It was called The Beautiful Widow, and with her hair plastered dramatically about her forehead, Leslie danced it all over the world. She and Petit, who traveled with the show, were together much of the time. Leslie began to smile again. She dated other men, made the columns often, but only with Roland did she look happy, animated. “I want to lead the intense, artistic life,” she wrote Geordie, believing it. “I don’t know what that is,” Geordie said, and filed for divorce. He charged mental cruelty and Leslie did not contest the action. Columnists reported that the divorce did not seem to affect her appetite, nor her excitement over being nominated for an Oscar for Lili. When she failed to win it, when Geordie blamed her for the failure of their marriage, Leslie had someone to turn to. But he was the wrong man.

Right from the beginning, her friends knew it was no good. “Yes, Leslie fell in love with Roland,” one of them said then. “She admires and respects and maybe hero-worships him. They were together in London, North Africa, New York, Washington, Monte Carlo. But the rub is that Roland Petit is in love with another dancer, Jeanmaire.”

The friend was right. Only weeks later, Roland Petit married Jeanmaire, and Leslie had lost again.

Very few people go through two such experiences and come out sparkling. Leslie couldn’t. More and more she withdrew into herself. She, who had always told everyone who would listen of her joys and loves, suddenly refused all interviews, was never available to the press. When her contract called her back to Hollywood, she went with the greatest reluctance. Hollywood was filled with memories, and Leslie had no use for memories.

So she threw herself into her work. She made The Glass Slipper with Michael Wilding and couldn’t help noticing how differently Liz Taylor had reacted to her first failure in love, when her marriage to charming, wealthy young Nicky Hilton went wrong. Elizabeth’s second choice had been a stable, adept, confident, slightly older man, able to comfort her, take care of her and provide her with the home and family she wanted. Leslie had for her comfort a one-room apartment. She painted it grey and white to match her mood, and refused to date. “I get up early and work too hard to be out late at night.”

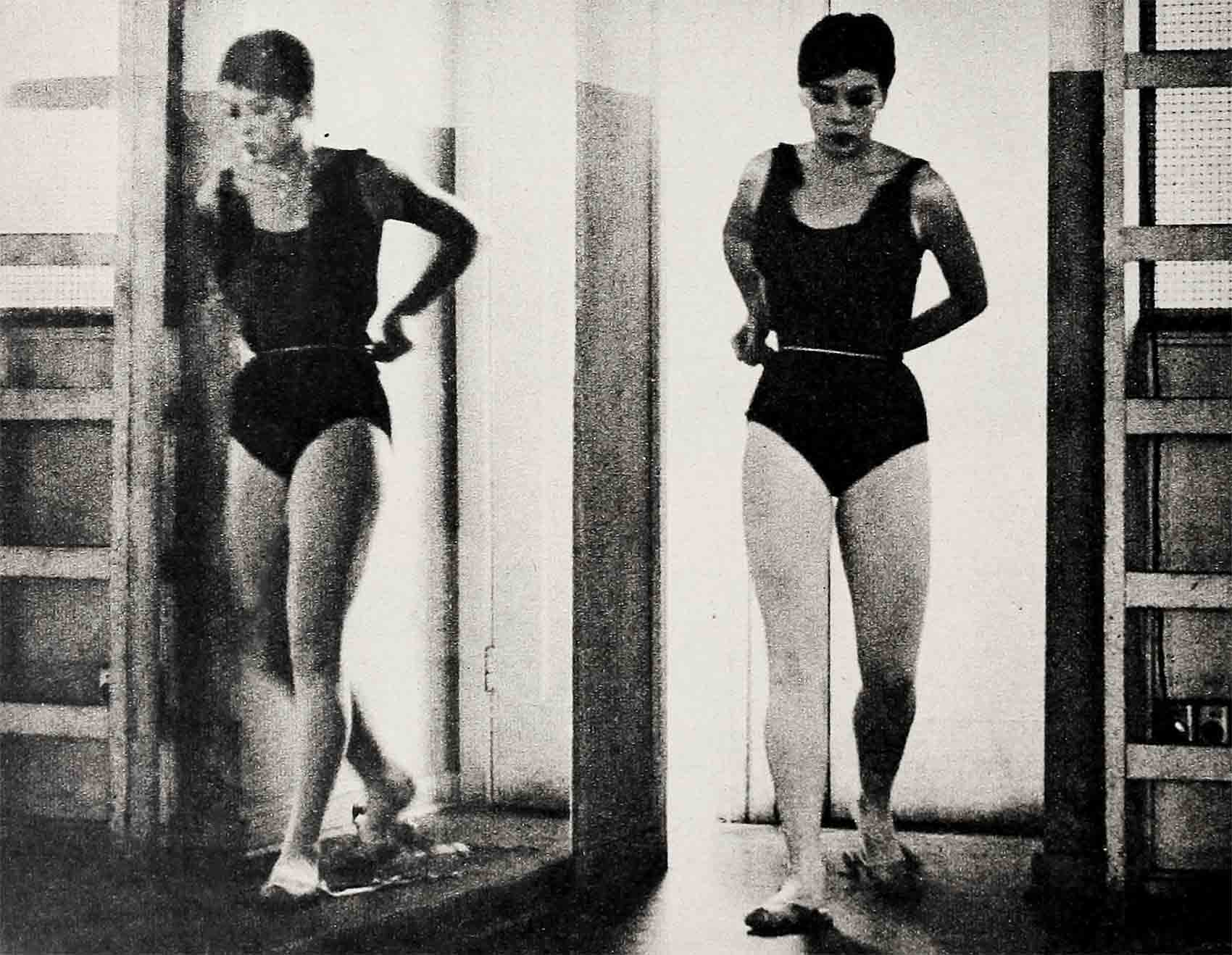

It was true that she worked hard. Fred Astaire, himself almost indefatigable, marveled at Leslie.

“I’ve never met anyone who was willing to work harder,” he said. “This girl has got a wonderful sense of organization. She listens very carefully as you outline the routine. She won’t dance until she’s sure she understands it. Then when she does, she insists on perfection. She is a wonderful girl and a marvelous dancer.”

But as soon as she could, Leslie ran away again. This time she went to Paris. There she opened in Jean Renoir’s play, Orvet. “I’m not sad at all,” she told friends, shivering in her backstage dressing room. No one believed her. The blue eyes were dull, the once tousled hair sternly pulled back from the drawn face.

A French newspaperman was asked how his countrymen felt about Leslie.

“She is a strange girl,” he said. “But that is true of all ballet stars. They live in a strange world, surrounded by men who care more for dancing than for anything else. Leslie, we feel, has been unlucky in love. She is again in that in-between-stage of getting over it.”

“Then she is still in love with Roland Petit,” the American said.

The Frenchman smiled. “You have got your Petits mixed up,” he said. “I think she is very fond of Robert Petit!”

Leslie had done it again.

Robert Petit is the manager of the Ballets de Paris. Of late he has become its producer. Throughout Leslie’s romance with Roland there had been rumors about Robert—talk that he was Leslie’s real love. Just when she turned to Robert no one really knew. But turn she did. At that time, he had a lot in common with Leslie. There was only one trouble. Robert Petit already had a girl.

Her name was Lillian Montevecchi. Like Leslie, she was a ballerina, a Roland Petit discovery, a member of the troupe of the Ballets de Paris, a girl who had danced with Leslie many times. Like Leslie, she was under contract to MGM. Unlike Leslie, Lillian managed to keep her man.

She had to act to do it. When she heard that a deep friendship was developing between Leslie and Robert, she got back to Paris in a hurry. After all, hers was the prior claim. Her return was a success. Immediately, the usually affable Robert started snapping at reporters who asked him about Leslie. “That rumor is false!” he would bark, refusing to be photographed or interviewed. Lillian and Robert are to be married any time now.

And that leaves Leslie where? “It leaves her,” a Parisian friend relates, “without a man. She sees Jeanmaire with Roland Petit. She sees Robert with Lillian. She thinks back over the days of her marriage to Hormel and it is only natural that she is sad. But she is young, attractive, there will always be others.”

The point is, which others? Leslie has indeed been unlucky at love. But could it be that she has made her own luck? Three times she has loved the wrong man. Not one was the man to give her what she wants most—the home and family she has dreamed of all her life. Geordie came closest, giving her for a while at least the illusion that her dream had come true.

She had loved housekeeping. When she first married Geordie they moved into a small apartment in Laurel Canyon. They paid $125 a month for it and Leslie did all the cooking and the housework. Eventually her in-laws sent Boots Shershing, a housekeeper, to help out. It was nice to have Boots there, leaving Leslie free to rest after her movie chores. But she would have been perfectly content without her. French women like housework, she said.

But when the idyll was over, to whom did she turn? Neither Roland nor Robert Petit was the sort to provide Leslie with a house to clean. Did the fact that Geordie had disillusioned her about her perfect love-nest mean that she must give up forever her dream of a home?

French women are economical. During her marriage Leslie saved money right and left, building a family nest-egg. She even made her own clothes, and did it happily. “Heck,” Geordie told her, “I’m in debt to the tune of $40,000!” But Geordie could afford to tease. He’d always known great wealth. Leslie had lived through a war and an occupation and had seen her father lose his pharmacy, leaving them in bitter poverty. But because her savings could not save her marriage, must Leslie feel that she should turn to that strange world of dance in which money is lavished freely upon luxuries, where material things count so highly?

Shortly after their marriage dissolved, real scandal broke over Geordie. He was accused of taking dope and tried for the offense. He was acquitted, but the names of many of his friends became headline news for weeks. He is home in Minnesota now, under the watchful eye of his family, forgetting the jazz career for which he longed, and settling into a prepared niche in their fabulous meat-packing business. But because Geordie proved unstable does not mean that Leslie should give up her need for a stable man. Because a dream goes awry one does not have to give up the dream. But that is what Leslie has done.

Her first marriage having proved a failure, she seems to have given up the idea of ever making another one work. She has turned to men to whom her dream is foreign. The pendulum has swung too far.

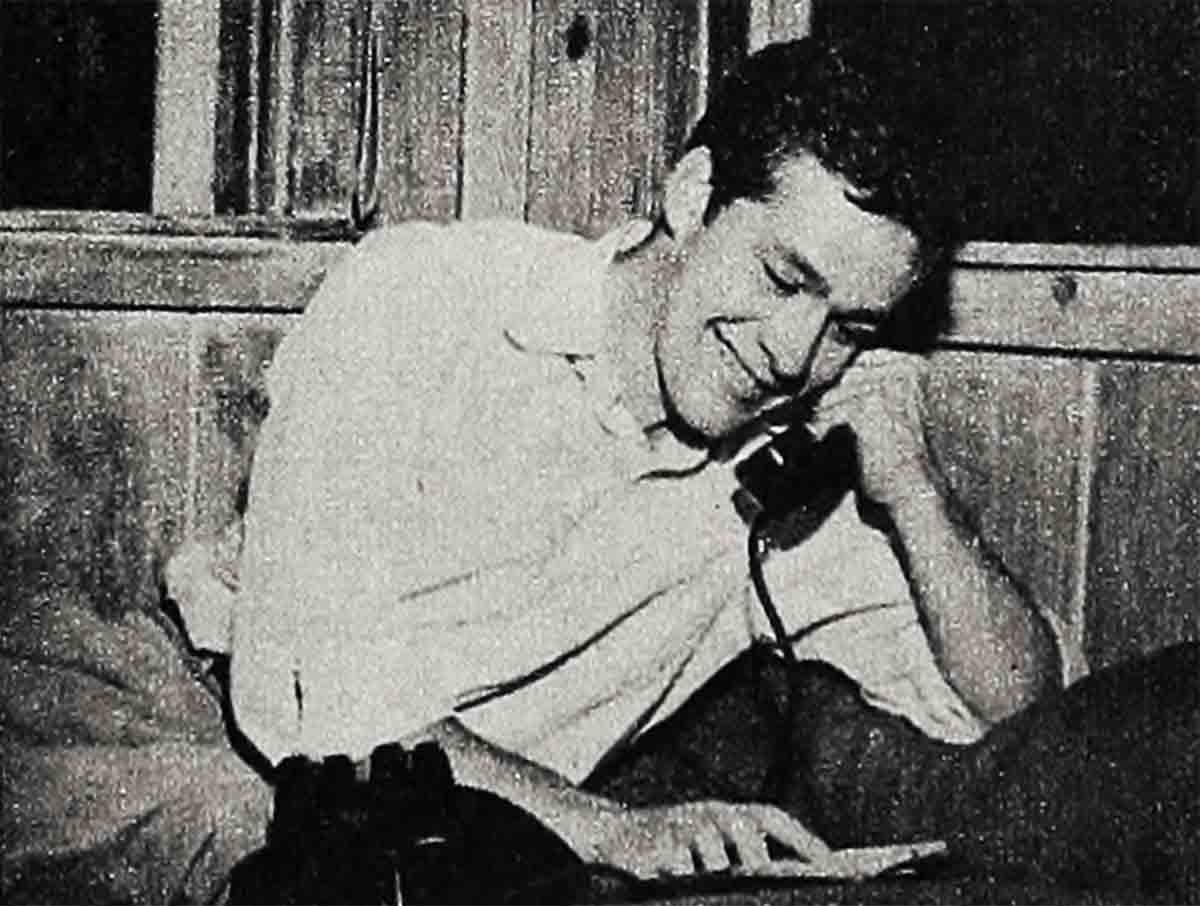

Back in Hollywood for Gaby, Leslie is dating again. This time he’s Jack Larson, a handsome, twenty-six-year-old actor she has known since 1951. Oddly enough, Roland Petit had originally introduced him to Leslie, and before her marriage they had dated. Now they have resumed their relationship. They dine together, spend much of their free time together. It was Jack who motored with Leslie to Long Beach to catch Judy Garland’s show. He is an actor, regularly appearing on the TV Superman series. And he seems to care very much for Miss Caron.

“Leslie is a wonderful girl,” he has said. “Sure, the years have changed her, made her more sharp, more alert. But I’ll do anything to make her happy. She sure deserves a little happiness.”

It sounds good. For Leslie’s sake, we hope that this time she chooses wisely. Certainly one of Cinderella’s gentleman callers should turn out to be Prince Charming—if only Cinderella learns to recognize him when he rides by.

THE END

—BY SUSAN WENDER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955