A Rather Remarkable Man

Just about a dozen years ago, in the heart of the city of London, a young Canadian named Alexander Knox might have been seen reading a novel by a young Englishman named James Hilton. If this sounds too dramatic, let us hastily add that he was not reading it because he liked it (even if he did), but because he was being paid to do so. In fact, he was a reviewer, and the paper he was reviewing for was the London Times. Now, being a novelist is anybody’s business (Knox himself has written novels, for that matter), but to be a reviewer on the London Times argues that Alexander Knox must have. been a rather remarkable young man in those days.

AUDIO BOOK

And he still is, in these days.

I went up to one of the high floors of Sunset Towers and met Alexander Knox for the first time a few weeks ago. He mentioned the earlier incident of the novel and we agreed that the world was a small place.

Presently there came along a couple of dry Martinis and it became clear to me then, as I stared about the room, that Knox was the kind of man who would accept what luxuries money can buy without enjoying them either too much or too little—without, in fact, thinking too carefully about them at all. It was quite a luxurious apartment for a man who lives alone—he is a bachelor by divorce—yet one had the curious impression that a less luxurious one would have suited Knox just as well, only he couldn’t find one. (And this, with the Hollywood apartment situation what it is, might quite possibly be the truth.)

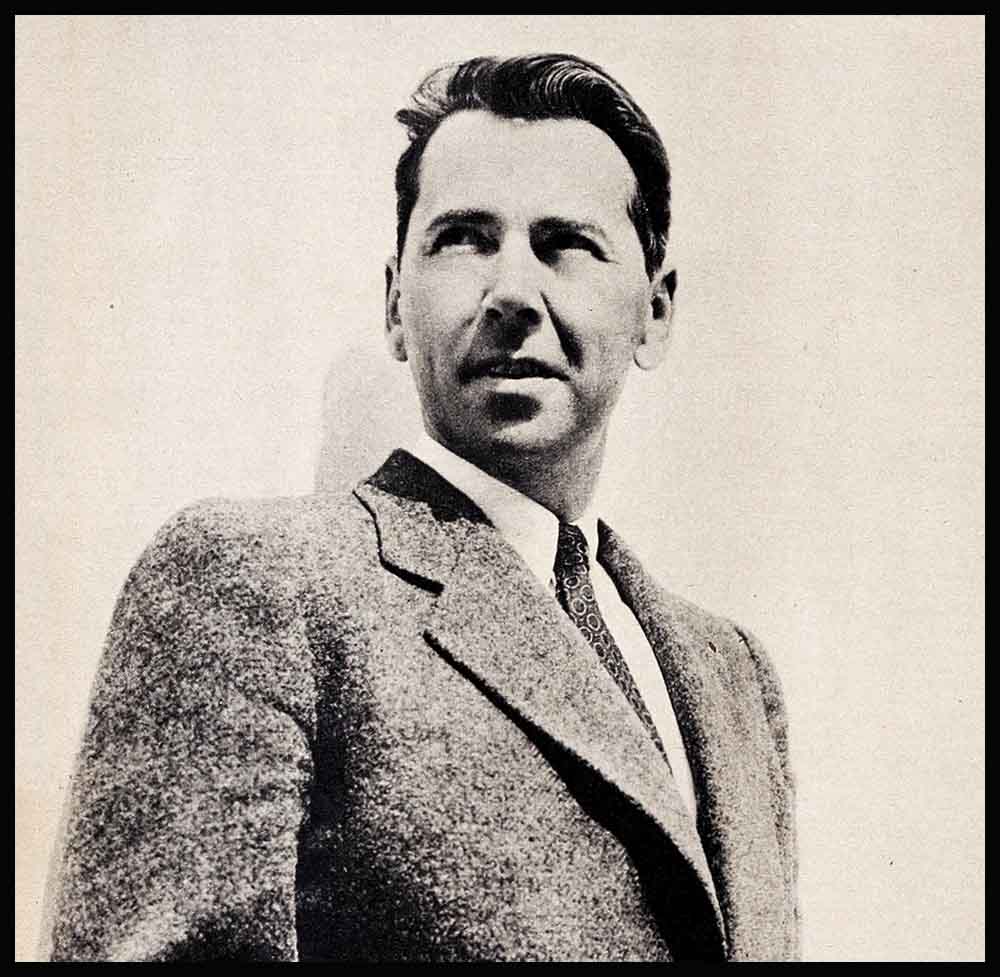

If I were a conscientious interviewer I should here describe the man, but why waste time, since everyone has seen or can see him in the picture “Wilson,” even to the Technicolor of his eyes. Besides, I am not a conscientious interviewer. I rely on the convenient and lazy principle that when you meet somebody you automatically remember what matters (to you, anyhow) and forget or perhaps don’t even notice what doesn’t matter. By that reckoning I couldn’t for the life of me recall how Alexander Knox was dressed, but I do remember how quickly we got into conversation about books, pictures, art, Hollywood and world politics. I thought that in appearance he reminded me a little bit of the English writer, J. B. Priestley. The angle of nose and chin, perhaps. . . .

Knox belongs to the new generation of Hollywood stars who shape so oddly into the category that they are already on their way to changing both Hollywood and the star system. It used to be that any male newcomer to the screen who wasn’t a glamour boy must be a character actor. If he was a character actor, and a good one, he could look forward to a long life of prosperity without too much publicity, but if he was a glamour boy he had to face the paradox that while the public was craziest over him he would be working his way up the lower rungs of the salary-option ladder, eventually to reach the top just about the time when gray hairs and a fickle public were beginning to show themselves.

With a man like Knox, however, the whole setup is different because it would be absurd from the outset to cast him either for “glamour” or “character”—as either a Robert Taylor or a Paul Muni. Indeed the only possible thing to say is that he’s an actor, and that the fame he has secured in “Wilson” neither enforces nor precludes any particular kind of thing he will do next.

In support of this argument one has only to glance at his previous picture roles to gather some notion of the man’s range. His first Hollywood film was “The Sea Wolf” with Edward G. Robinson, in which he played the shipwrecked author, a man of physical fear but mental courage. After that there were the memorable moments in “This Above All” as the gentle clergyman and in “None Shall Escape” as the fanatical Nazi leader which in Knox’s hands had the sharpness of a steel engraving.

So Knox is a star, but like many of the newer stars, he doesn’t fit into the star system; and when enough people don’t fit a system it is the system that has to be changed. Knox’s biography is interesting because, by its very variety and individuality, it is becoming typical of this newer Hollywood star-vintage. That it is a riper, mellower vintage none will deny, for these young men with a future are all the more interesting because they have a past.

Take Knox, for instance. He was born in Ontario, Canada, thirty-odd years ago. His father (like Wilson’s) was a Presbyterian minister, and his mother (also like Wilson’s mother) came from a long line of Presbyterian ministers. Maybe the original John Knox was one of them. That Scottish reformer would make a dour ancestor for anyone, though distant and eminent enough to be proud of.

Alexander went to grammar school and high school in London, Ontario, eventually enrolling as a medical student at Western Ontario University.

But he soon found he preferred writing, elocution, acting, newspaper work, debating, politics and what not. He was ambitious, self-confident, sure of himself—and if you are not sure of yourself before you are twenty, what chance have you later on? He played Hamlet in a university production, then joined the Boston Repertory Theatre before his college career was finished. The year in which this happened was 1929—just about the hardest to be ambitious in, even for a youth. So presently he went to the other London. That milder, less hectic atmosphere proved congenial, so that within a short time Knox found himself playing the part of a young American in an Edgar Wallace play in a West End theater. He was also writing his first novel, as well as his first reviews of other people’s novels.

For several years after that he crossed the Atlantic back and forth, “commuting,” as he says, between England, New York and Canada. 1937 saw him putting in a season at London’s celebrated Old Vic. Then he appeared in a Bernard Shaw play called “Geneva”—which, with prophetic appropriateness so far as Knox was concerned, dealt with the League of Nations. In between whiles he even wrote a play himself and acted in it; then he took a writing assignment with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

If one thing had become almost inevitable by this time it was that Hollywood would go after him, even if he didn’t choose to go after Hollywood. He didn’t, particularly, but Hollywood did—characteristically and capriciously, so that presently, with a touch of the divinity that shapes people’s ends, “Wilson” began to appear on his own and Hollywood’s horizon.

A matter of general as well as technical interest is that he never took the usual kind of screen test for “Wilson.” He made a voice-recording of the entire part, and it was the voice, one gathers, that clinched the matter. (This, I suppose, gives him something—if anything—in common with Frank Sinatra.)

Of course Knox and I talked a good deal about Wilson—not only the picture, but the man in the picture, and also the man in history. Knox is the sort of person who would naturally read all the books about Wilson he could get hold of, for sheer interest in the subject—in contradistinction, let us say, to Madame Sarah Bernhardt, whose acting ability and silver-tongued utterance were both superb, but whose intellectual concern with what she was up to was sometimes so slight that she was said not to read a play completely, but merely to know her own cues in it. (It is only fair to add that some of the plays she appeared in fully justified this economy of effort.)

Anyhow, it did not really surprise me to find that Knox was something of an authority on Wilson, since intellectual as well as artistic understanding was everywhere evident in his screen portrayal. all of which doubtless led us to a discussion of Hollywood’s rapidly expanding mental level, and its consequent assortment of new ideas and hangovers of old ones.

There are still ad ,writers in show business who think that the public can only be lured to see a picture like “Wilson” by being assured that it is the love story of a president. (So it is, too—the story of a president’s love for humanity, but that sort of love doesn’t count at the box office, so the old-timers tell you . . . and the absurd part about that argument is that “Wilson” has done good business, thereby proving how far the new-generation public is ahead of old-generation publicity.)

Knox, I found, has some forthright ideas about Hollywood. Like all modern-thinking people he realizes the power of motion pictures in the world, and like most people who have approached Hollywood with some sophisticated experience of other entertainment fields, he finds plenty in it to praise as well as criticize. He thinks Hollywood has not been given enough credit—especially by highbrow film reviewers, some of whom write stuff that goes as far overboard in one direction as the puffery of the ad writer does in another. Because the movies are a mass-art, like radio; and however good a film is, it fails in its prime function if it appeals only to the small minority. The great achievement of a production like “Wilson” is that it can enthrall the mass-audience. And so Knox realizes that the uplift of Hollywood’s brow, however desirable, is only worth while so long as both feet are kept on the ground, the ground being the heart and understanding of the people.

So we talked and talked and presently it was time for me to leave, and only when he asked if I had enough material for an interview did I remember it was supposed to be one and not just a visit.

Our final remarks, I think, were about Bernard Shaw. We had both met him, admired him, read him and possessed letters from him in that familiar long-looped Shavian handwriting. And Shaw was a world-famous man before either of us was born, and long before Hollywood was born. That is a sobering and yet also an exciting thought, when one sees a picture like “Wilson.” Pictures are so new in the world and yet they have already gone so far.

That the new generation of actors like Knox will see and take them much further is one of the sure things one can prophesy.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1945

AUDIO BOOK