America Falls In Love Again!

It was late evening in the home of a very precious, very famous little girl. Her parents were still up, but the child was deep in sleep.

Suddenly, out of the quiet, an alarm went off. The house reacted like a tilted pinball machine! Bells clanged, fights blazed, sirens screeched. A huge police dog—one trained to bite—leaped for the child’s door, looking for an intruder to sink his teeth into. A bodyguard who slept in the next room darted out with gun in hand.

Nobody in the hail, nobody in sight. He opened the child’s door and looked around the room for trouble. No trouble! She lay with fair hair tumbled on the pillow—looking the way imps do when they’re sleeping like angels.

“False alarm,” said the bodyguard, looking relieved. As it turned out, it was an “accidental” alarm. The child’s father had just inadvertently tripped the master switch of a system meant to make the whole house “kidnap-proof.” Because there had been a threat to the girl’s safety—to her life. It was a terrible scare—and when the news came out it rocked t he nation!

But the moppet never knew a thing about it. Her parents protected her from all such frightening knowledge.

Who was this well-guarded little girl?

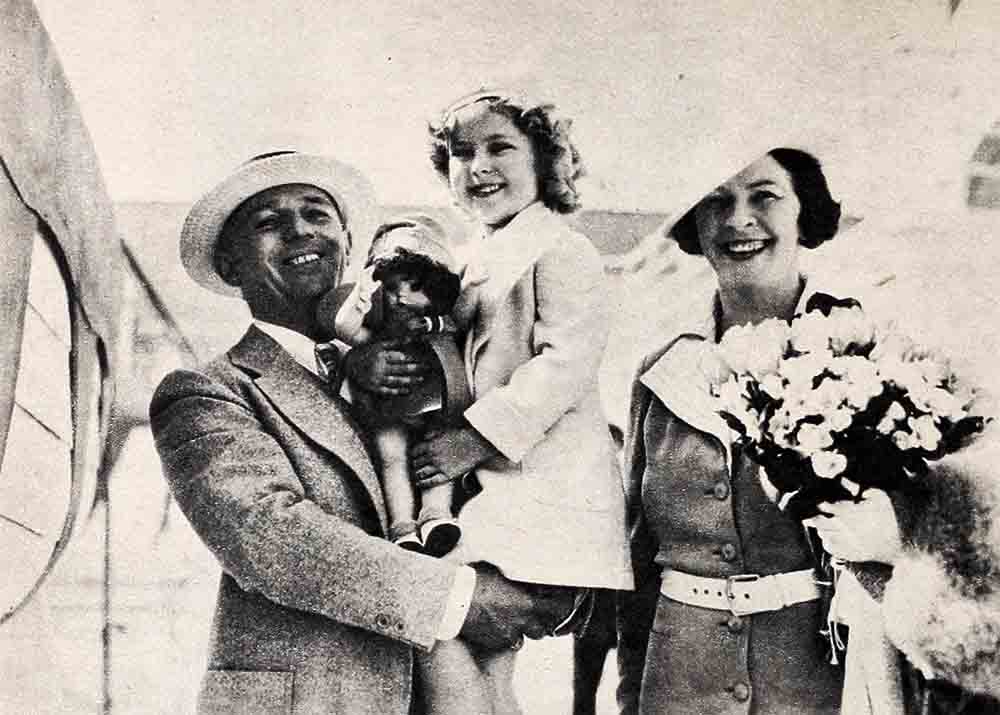

It seems like yesterday, but it was really a long time ago. The little girl was Shirley Temple.

And everybody in America cared terribly, because this was our own dimpled darling who made us laugh and cry and forget our troubles. America—the whole world— was in love with her.

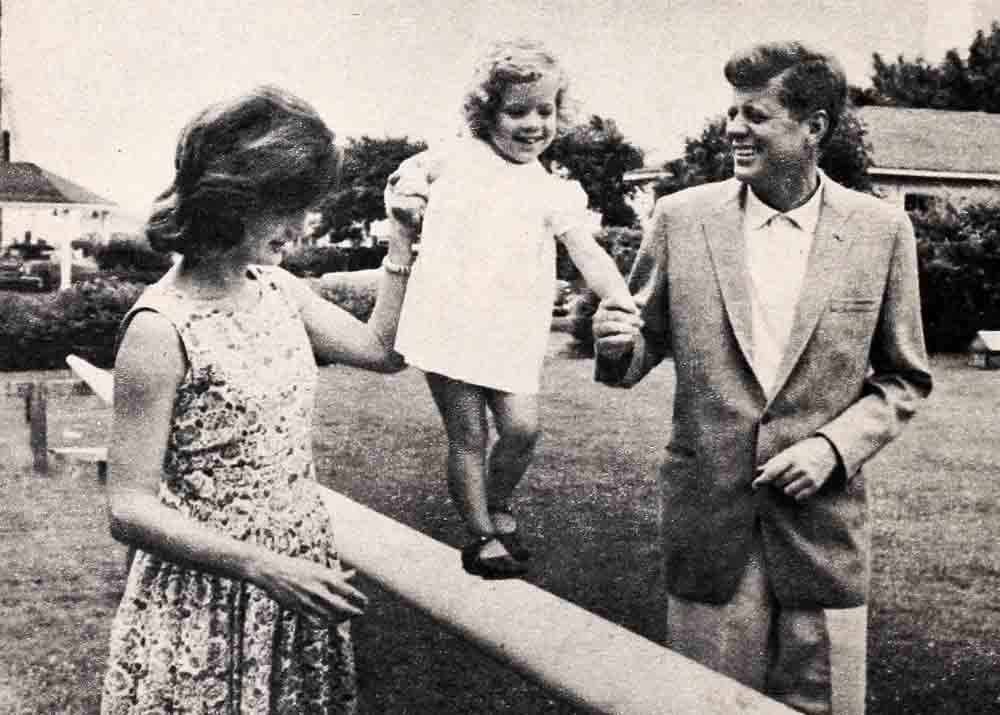

Now, more than twenty years later, we’re in love again! For the first time since Shirley Temple, a whole nation is eager to know about one little girl—what she eats, wears, says and does. We can’t get enough of her face on magazine covers, in newspapers. That Caroline Kennedy, we say—cute as a button!

Many people don’t notice—at first—how much our new national sweetheart is like our first one. That’s because Shirley was a star in her own right, while Caroline’s a star because she’s the cutest Presidential daughter in history. But they’re alike, all right! It isn’t so much that both were threatened by kidnappers—personal danger is often one price of popularity. What’s remarkable is their strongly parallel reaction to those scares—and to fame, adulation and the spotlight’s glare on their private lives. Caroline takes it all just the way Shirley took it—she pays it no mind! She doesn’t even know it’s happening. She’s too busy playing.

Watching her, loving her, it’s hard not to worry whether she can keep on that way. Caroline has been living at the White House for more than a year out of her four, and more than likely she’ll be in it another seven. How soon before she becomes aware that she’s a very special and closely guarded little girl? That wherever she walks and plays, the Secret Service men are never far off? And for all her privileges, she must live without many freedoms that less privileged youngsters take for granted?

Yet there’s no reason why Caroline shouldn’t grow up the unspoiled girl and fine woman that Shirley Temple became. She’s got what Shirley had—a pair of sensible parents.

Somehow, almost instinctively, both their mothers seem to have understood—each in her own time—America’s need to fail in love with a little girl, whether she was an actress or the President’s daughter. Shirley became our ray of sunshine in the darkest depression, when frightened people hungered for something to put their faith into. Now it is Caroline’s turn to lighten troubled hearts. Dr. Frank S. Caprio, the eminent psychiatrist, believes that Caroline is a sort of “heaven” in the hell of depressing international events. And that, like Shirley, she symbolizes “warmth and the family unit.” This is certainly still true of the grown-up Shirley. Even when she was a story-book lady on TV, she was a wife and mother first.

But when Shirley was little, it was a miracle that her curly little head wasn’t turned. She was a movie actress at three, a star at six, a millionaire at ten. The American Legion made her an honorary colonel; the Texas Rangers made her a captain. She was an honorary G-woman, a mascot in the Chilean Navy. She had her own bungalow on the studio lot, and at home a glass-brick playhouse as big as a real house. It had a movie projector and a private soda fountain. Best of all, it was filled with dolls that poured in from admirers all over the world.

What’s more, little girls stood in Stores all over the country and wept if their mothers wouldn’t buy them a Shirley Temple dress, or a Shirley Temple doll. (And maybe you can’t go out and buy one of them today—but you can buy a Caroline Kennedy doll!)

It was small wonder then that the nation was horrified, back in 1936, when an extortionist mailed an anonymous letter to George Temple demanding: “Unless $25,000 is dropped from an airplane near Grant, Nebraska, on May 15, the life of Shirley Temple will be endangered.”

Police were convinced this was no mere crank letter. But they were stymied. When the letter arrived, it was handled like any other piece of Shirley’s enormous fan mail. Only after the envelope was destroyed were the unusual contents discovered.

Now the G-men stepped into the case. In their technical laboratory in Washington, the letter was subjected to every known scientific test. And one paid off. The type of paper was traced back to its manufacturer. His records showed that it could have been bought only in Stores in Grant or Madrid, both in Nebraska.

At last the suspect, a sixteen-year-old boy, was tracked down, tried and sentenced to a five-year term at the National Training School in Washington. When the headlines announcing the capture and conviction of the criminal hit the newsstands, the world breathed a sigh of relief. Its little sweetheart, Shirley Temple, was safe.

The only one who heaved no sighs was Shirley. She was on a leisurely motor trip through California with her mother and dad. Their chauffeur secretly doubled as her bodyguard, and everything seemed normal to the famous eight-year-old. At the moment the extortionist was being picked up, she was playing checkers with a new girl friend in a hotel lobby in Eureka, California. Her parents had never breathed one word of the danger to her.

As to her counterpart—not only doesn’t Caroline Kennedy know that she, too, was the center of a kidnap scare last year, that she was saved from near-drowning in a swimming pool last summer but, for a long time, she wasn’t even told that her father was President of the United States. The Kennedys, believing that there are some facts a little girl doesn’t need to know too soon, tried not to make a “thing” of her Daddy’s exalted position.

But a few months ago, it became apparent that Caroline had found out. She was proudly wheeling her baby brother in his carriage when the knowledge slipped out, Beaming at a perfect stranger she asked, “Would you like to see the President’s son?”

Awareness is setting in. There are bound to be other instances—like the matter of playmates and schools. For all the notable lack of Kennedy snobbery. Caroline has her own circle of little friends from Washington’s higher echelons, and these are her “classmates” at nursery school. The latter institution of learning evolved when Caroline’s trips to and from ballet classes became so over-publicized that her father, turning down photographers’ pleas, decreed, “I think it’s time for Caroline to be retired.” She wasn’t—but the ballet classes were moved into the safe confines of the White House, and then developed into a full-scale nursery school.

But when Caroline reaches “real school” age, everyone who reads a newspaper will have an opinion about whatever school is chosen for Caroline. Joseph Kennedy could educate his children where he pleased. Jack went to an extremely Progressive prep school. But his father was only an Ambassador, not the President.

And all her life Caroline will be evaluated as the daughter of a President—even after the Kennedys leave the White House. When she becomes a teenager, she will still experience the same lack of privacy as Margaret Truman and Princess Margaret. Her romances, her marriage, the children she bears—they will be followed with the same passionate interest as a movie star’s. She can never again achieve anonymity.

But for now, the Kennedys try to keep her life on a normal level—for as long as they can. Perhaps they remember all top well what a critic once said of Margaret Truman’s vocal ambitions, that she was as good a singer as “any average American girl whose father is President of the United States.”

Jacqueline Kennedy is deeply concerned with her children—for all the time she must spend away from them. As the President’s wife she carries a heavy schedule of activities outside the home. And as an international figure—a world charmer—she is at Jack’s side when he jets to Latin America, Europe, or wherever diplomacy beckons. But like any average housewife, she “can’t be two places at once.” So as a mother she must depend more on the quality than the quantity of her relationship ,with her youngsters. Their happy times together, often caught by cameras, make some of the most charming candid photographs of our times.

“If you bungle raising your own children,” Jackie Kennedy once said, “I don’t think whatever else you do well matters very much.”

In this delicate matter of trying to raise a child normally under most abnormal conditions, Jacqueline Kennedy has a good model in Gertrude Temple. When Shirley was at her peak of stardom Mrs. Temple said, “We have been strict, very strict with her, and none of us spoil her.” Then she added with a smile, “I want Shirley always to feel that I am her best friend, and that if she needs advice, I am the one she should confide in.”

Gertrude Temple and Jacqueline Kennedy have even made use of the same wonderful technique to preserve the naturalness of their children—the magic of “make-believe.” For a long time Shirley didn’t know she was a movie actress. It was all a game she was “playing.”

When she made “Baby Takes a Bow,” there was a birthday party sequence in the script, and in all innocence Shirley thought the director had arranged the party just for her. So she invited all her friends.

The director was equal to the occasion. “Fine,” he said, “we’ll have two parties—one now and one later. Your studio friends can come to the first one, and your home friends can come to the other.”

Shirley was thrilled. Two birthday parties—and it wasn’t even her birthday yet!

Occasionally, however, her fondness for “let’s pretend” got a little out of hand. One Sunday afternoon Mrs. Temple looked out of the window of her house and saw a number of autos jamming up the road. She was used to cars stopping or slowing down as tourists tried to get a peek at Shirley, but never this many. And what were all those people doing on her front lawn?

She called “Shirley! Shirley!” No answer. She ran outside.

There was Shirley, behind an old box set up on the sidewalk. On it were grass-decorated mud pies. Men and women were pressing bills into her hands, while she gleefully shouted, “Mud pies! Who’ll buy my delicious mud pies?” She didn’t quite understand why everyone insisted that she print her name for them, too, on pieces of paper and old envelopes. But so long as she sold her mud pies, she didn’t mind.

Caroline, too, loves the world of “make-believe.” She enters her “let’s pretend” world every day, at about the time that grown-ups call “the cocktail hour.” That’s when Daddy gets back from the office. She herself has already eaten in the nursery, but she’s allowed to sip a Coke while her father drinks something that “tastes awful” called a Scotch or a Martini. She sits on his knee, snug in her pajamas, while he reads her favorites, “The Three Bears” or “Snow White.” As she listens, she becomes Goldilocks, she is Snow White.

Caroline’s delight in “pretending” extends to her baby brother. He is “my new baby, John”—not Jack—“because his name is John.” And he is definitely “her” baby.

Shirley had two brothers, but they were both much older than she. So when she was just a little older than Caroline is now, she solemnly announced, “I’m going to have a baby.”

Wouldn’t that bring problems, she was asked. Would she still have time to play “make-believe” in front of the cameras?

“Oh, I’ll do that, too,” she replied. “But it will keep me pretty busy dressing my baby, you know.” Yes, she was also going to go to school for the first time soon, “but first, I have to have my baby!”

Grown-ups, no matter how famous they may be, are only important if you can play with them. To Shirley, Rosa Ponselle, the famous opera singer, was “nice” because she taught her an old Italian lullaby to sing to “the baby” she was going to have. Henry Morgenthau, Sr., former American Minister to Turkey, was “fun” because he came to a party she gave and acted just like the other “kids” there. Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the President’s wife, was “swell” because “she smiled a lot.” When Shirley visited Washington, she had a heart-to-heart talk with the President himself, whom she liked “very much.” Asked what they talked about, she answered promptly, “I told him I lost a tooth. It fell out while I was eating a sandwich.”

Caroline has the same easy attitude with adults. When former President Harry S. Truman showed up at the White House early one morning, she peeked out at him from under her father’s desk and said, “You used to live in our house but you went away.”

When she attended her first white-tie function at the Capitol—a formal shindig for members of the diplomatic corps—she entertained the guests by doing a somersault for them on the red carpet near the piano.

Even rock-ribbed Republicans melt at her charms, although one GOP big-wig remarked ruefully, “She’ll be the Democrats’ most powerful secret weapon in 1964.”

Yes, it’s fun to be the President’s little girl. There are plenty of compensations to offset the problems. If it means hovering Secret Service men, it also means the privilege of growing up in the historic beauty of the White House . . . knowing the sea aboard the spacious Presidential yacht . . . being on friendly terms with the world’s most famous men and women . . . receiving presents from them—like Pushinka, the little white dog sent by Premier Khrushchev.

And with all this, Caroline has a mother who takes time out to teach her how to ride Tex, the Yucatan pony that was a present from Vice President Lyndon Johnson . . . and a father who reads her bed-time stories whenever affairs of State permit.

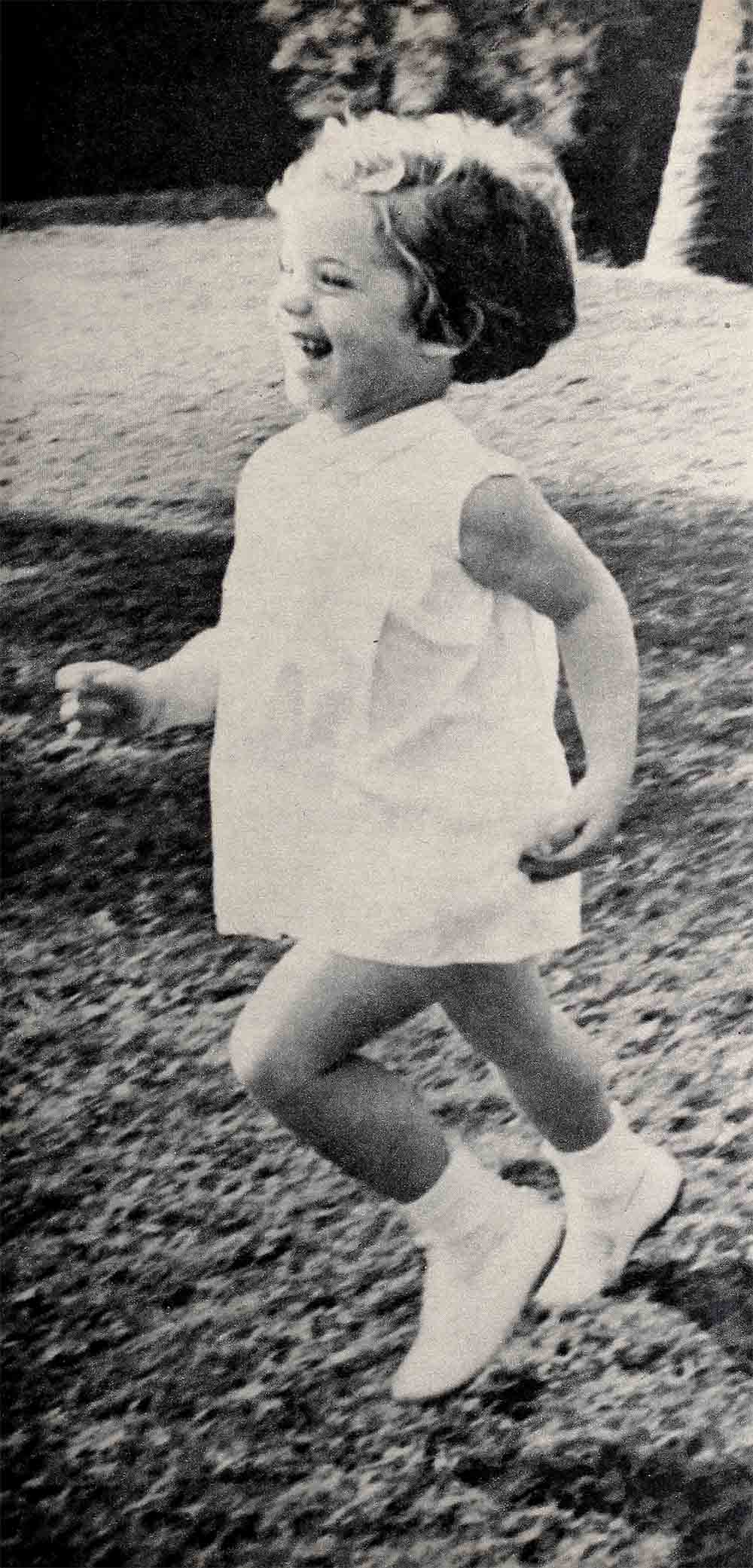

Caroline and Shirley, Shirley and Caroline—their images fuse together. It’s amazing how much alike Caroline today and Shirley of twenty-five years ago look. Same coloring, same percolating vivacity. Same amazing ability to creep into the hearts of everyone and to make us all young again.

Two final pictures.

Little Shirley sitting on the lap of a famous judge, a brilliant, famous, but cold man. His face is wrinkled in a smile, as when ice breaks in the spring and life pushes through. He’s smiling down at a little girl, because a little girl is smiling up at him.

Little Caroline, at a time of international crisis, bravely facing the press. Answering the question, “What is your father doing in there?” Her words are to the point. No shilly-shallying, no false diplomacy. “He isn’t doing anything; he’s just sitting there with his shoes off.”

Yes indeed, they are two of a kind! Two fantastically celebrated little girls with an identical gift, a gift for making a whole world laugh with them, cry with them and love them.

Shirley Temple grew up unspoiled and sweet. There is no reason to expect less from Caroline Kennedy. The carpers and wailers who ask, “How can she grow up normally when she’s so over-publicized?” can find their answer in America’s first dimpled darling . . . and stop worrying . . . and let the Kennedys bring up their own little daughter in their own way.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1962