Hey There, You With The Stars In Your Eyes—Janet Leigh

You are Destiny’s darling.

You’re the inspiration for every small-town girl who dreams of making good in Hollywood . . . and of being in your own magic shoes. You’re the Cinderella Girl of all time. And yours is the Cinderella story nobody would ever believe on film. Today all across America other young feminine hopefuls wish upon your star and dream of being exactly where you are. For you’re the girl who shines bright in starlet town and captured a Prince Charming as well.

A picture, they say, is worth ten thousand words. And yours has been worth infinitely more. But this, JANET LEIGH, is your life—and your destiny. . .

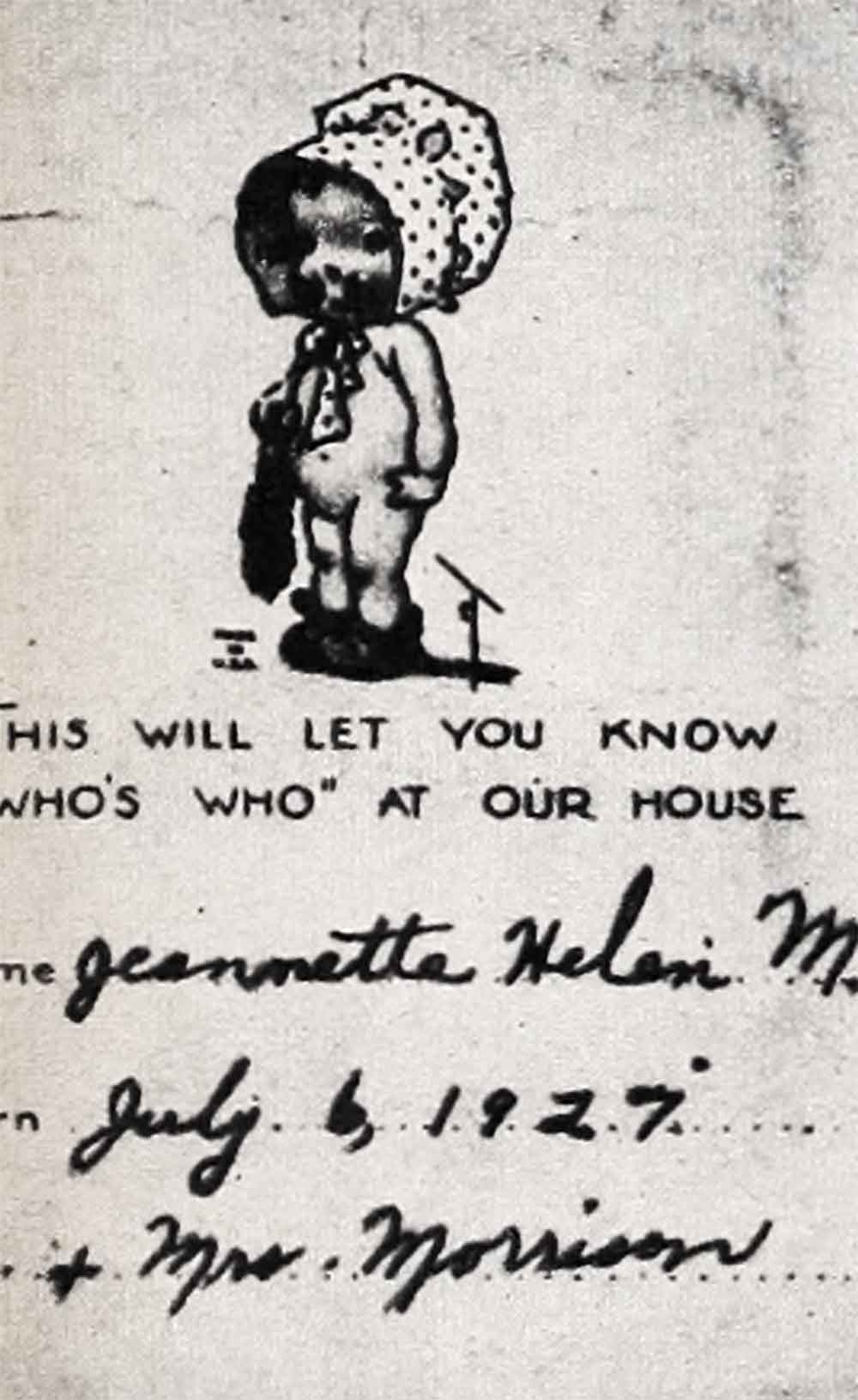

Like any true Cinderella story, yours begins once upon a time. That time is 3:30 P.M. on July 6, 1927, in the small town of Merced in northern California. And according to your proud father, Fred Morrison, it’s Christmas in July. . . .

“Jeanette was the most perfectly formed little baby I’ve ever seen—and I’m not just saying that because I’m her father either. To tell the truth, I was a little afraid to look at her when she was first born. I’d heard a lot about little babies being so red and funny-looking, and I was relieved to find she wasn’t like that. She looked like a little doll from the hour she was born. She weighed in at six and one-half pounds, with big blue eyes and a lot of light auburn hair.”

Yes—you’re the glamour girl of the Merced Hospital. No doubt about that. And according to your mother, Helen Morrison, your proud pop “stole” a ride and broke all records getting there for the preview. . . .

“Fred had taken me to the hospital the night before. When the doctor told him the baby wouldn’t be born until late the next day, he went on to work. They promised to call him in time. But at 3:15 when he called the hospital and asked, ‘How’s my wife?’ they told him I was in the delivery room. We didn’t have a car, but when Fred dashed wildly out the door of the ice company where he worked, he saw a truck standing there with the motor running, and he jumped in and took off. He had a time explaining later. The fellow thought sure somebody had. stolen his car. We both wanted a girl. And I was glad she had her father’s snub nose—I’ve always hated mine. We didn’t have a name for her, and somehow every name we thought of wasn’t good enough for her. Finally we decided on Jeanette. . . .”

When you’re nine months old, you pose for your first official portrait, wearing baby-blue organdy, a fluted blue organdy bonnet and your first pair of black patent-leather slippers. But not even your own proud parents could know how much of your life is to be spent looking into the lens of a camera. You walk on your first birthday. And you’re not too good in that “how-now-brown-cow” department for quite some time. Ice cream is “buda buda.” And the best you can do with your Aunt Pearl’s name is “Popo.” Years later when she is your secretary in Hollywood, Auntie Popo will still be her name. . . .

When you’re two years old your parents move to Stockton, California, and your father looks for work there. These are tough times, as your mother now recalls:

“We stayed with my folks at first. Seven of us in a small two-bedroom place in a court. Fred got a temporary job helping out on an ice wagon, and for a while there we lived on a quarter a day! In those days you could buy a nickel’s worth of hamburger and get a soupbone on the side. And for another five cents I’d get a couple of turnips, a carrot and perhaps a piece of cabbage for soup. Jeanette was a big girl before she knew anybody ever bought more than three eggs at one time. We moved—well—just about every time the rent came around.”

In 1929 you’re two years old and yours is a smile that will melt the flintiest heart. Your father gets a job with the Grover Grider Electric Company in Stockton, and on the strength of the promised position—and your charm—you move into an apartment without paying anything down on the rent. According to your father, you’re the family’s best security. . . .

“We didn’t have a dime to pay down on the rent or for food or to turn the lights and gas on. And I was too proud to ask the boss for an advance. The landlady’s name was Mrs. Schnake, and I put our problem to her very frankly—and she was frankly hesitant. “I’ve just been beaten out of two weeks’ rent,” she said. Then she looked at Jeanette again. “But you have this baby—I think I’ll trust you.” Then we went to the corner grocery and gave him the story and asked if we could charge a few things. He looked at the baby—and we went away with groceries, a can of canned heat to cook with and candles for light.”

Yes, money is scarce during your early years, but yours is a family rich in love and laughter and understanding. You grow up with a sense of values that won’t desert you in the glamorous years ahead. Tough times only strengthen your family ties.

On Halloween, 1931, you make your first appearance in costume, and you are a “howling” success—according to your Mom:

“We had a little party for Jeanette at home—just the three of us. She had a mask on and a white sheet draped around her, and she had one of those serpentine things you blow on which delighted her no end. Our apartment was on the street, and we had all the lights out but a candle in a pumpkin. Jeanette would blow this thing out the window at everybody passing along the sidewalk. She had an hilarious time.”

In 1933 you enter Weber Grammar School in Stockton. Your father’s still working at the electric company, your mother’s working at Wright’s Coffee Shop to help out with family finances, and your Aunt Pearl, eight years your senior, lives with you and “baby-sits” while your parents work. Your “Auntie Popo” has a few of her own vivid memories of you:

“I used to love to dress Jeanette up and take her places, and she was like a little sister—always tagging after me. We’d go to school together, eat lunch together, and on Saturdays we would go to the movies all day long. We’d go to the Mickey Mouse movie in the morning, stay for the matinee, and if we could talk Fred and Helen into it we’d go back for another show that night.

“I married when I was sixteen. We lived in Oakland, and Jeanette would come visit us. My husband and I were just kids, too, but Jeanette would call us ‘Mommy’ and ‘Daddy’ just for fun. She was eight years old and almost as big as I was. She’d skate down the hill by the house yelling, ‘Mommy—catch me!’ People going by would give us the funniest look. The neighbors thought I was a real child-bride. We were the shock of the town!”

In 1935, too, you twirl a baton as majorette of the Scouts and you win a silver cup engraved “First Prize Mascot” for Pyramid No. Five. Your band, in fact, wins a prize three years in a row among competitive cities and Pyramids. One of your public, your Pop, gives a firsthand report:

“Our daughter was so proud of that drum-majorette outfit. It was white, trimmed with gold braid, and she wore white Russian ‘dress-up’ boots with it. Her tall majorette hat was made of tin foil—and she really loved that. ‘It shines just like diamonds in the sun,’ she said. Once she marched for miles—all through the park and the downtown section—twirling that baton with an open blister on her hand. For a prize one year they told her she could pick out whatever she ‘really wanted’ in the local jewelry store. Jeanette said she really wanted a ‘red plaid raincoat and a hat to match.’ Her mother couldn’t stand it—our daughter being turned loose in a jewelry store where she could pick out a watch or bracelet and coming up with something like that. ‘Jeanette you mustwant something here,’ she said. The girl wouldn’t budge, though—and a plaid raincoat she got!”

But the real adventure you look forward to so eagerly in childhood, Jeanette, is the two-weeks vacation you spend every summer at your beloved grandmother’s in Merced. You pack and repack your little suitcase for weeks ahead of time. Your grandmother, blinded for years, has never seen you. She strokes your golden-brown hair, she feels the snub nose and contours of your face—and others give her every detail about you. As for you, you are her eyes when you are with her. You read to her. You go to movies together, and you describe all the stars to her. . . .

When you are ten years old, tragedy comes very close to you, and you are almost blinded, too. You’re playing “cops and robbers” with a little playmate in the park, using wooden guns with taut rubber bands on the end of them for “ammunition.” “Janie, look,” he says. You turn to look at him, and he lets loose with a rubber band, accidentally striking you in the eye. Your mother rushes you to the doctor. You wear a black patch over it, then dark glasses for weeks. The rubber band missed the pupil by a whisper, or you would have been blind for life. It would seem Fate already is your very good friend.

During the Christmas vacation in 1939 you make your first “professional” appearance. Are you scared, Jeanette?

“Scared? I was petrified. Absolutely turned to stone. We were doing a little skit built around ‘Faith, Hope and Charity—the greatest of these is Love.’ I sang the ‘Wishing Well Song’—‘I’m wishing for the one I love to find me some day . . . ‘I’m hoping—la da da de da . . .’ I was Love, and I wore a devastating cheesecloth thing—an eighth-grader’s Christian Dior. . . .”

This is the year, too, you’re voted “Prettiest Eyes” in Weber Grammar School and graduate mid-term from the eighth grade. The schools are crowded in Stockton and your I.Q. is so high that the teachers keep having you skip grades. And this, “Little Miss Love,” is an important day in more ways than one. For the first time your Mother allows you to wear rouge and a little lipstick, thereby saving your pride with the other girl grads who are much older than you. . . .

You’re in high school now, and this is your life. . . . You make the Honor Society three years in a row. You sing in the Presbyterian choir and with Frank Thornton (“Teach”) Smith’s high school “Troubadours.” The “Bob-Inn” is the “sharp” place to go for hamburgers and chocolate malts. As soon as you’re allowed to ride with a boy in a car, the big adventure is to drive out to the edge of town to “Stan’s Drive-In.” As for your first date . . . remember that, Jeanette?

“That I couldn’t forget. My first real date was with Dick Doane. We went to a football game at Lodi and my parents drove us. This was, of course, after a courtship of many months, attending Christian Endeavor together. But our real big evening was a Christmas dance. I had a new $12.95 aqua-colored formal that was a vision. It just kind of floated along. I had my hair done up. Dick sent me a white orchid, my first. For Christmas Mother and Daddy gave me a little short white rabbit fur jacket. My first fur coat! They let me open my present in advance, so I could wear it to the dance. When I opened the door that night for Dick, he sort of gasped ‘Oohhh.’ I’ve never enjoyed an evening more. I was really living that night.”

You’re doubly proud of that white rabbit fur jacket, Jeanette. For you know your parents will probably be paying for it all the following year. Unwrapping it, you look quickly at your mother’s hand—to see if her watch and engagement ring—with its two small sapphires and wink of a diamond—are still there. The family jewels move in and out of the local pawn shop regularly during these earlier years.

For you 1940 is in many ways a very grim year. And one better to forget. You move to Merced for that year. Your beloved grandfather is incurably ill, and your blind grandmother needs help and reassurance. Your dad is working as an automobile salesman, but there’s a national emergency and there are no new cars to sell. You love going to school in Merced, you make many friends, and when your father plans to go back to Stockton and take a job, you don’t want to move back there. On an impulse you elope to Reno with a young school friend. And for that today your parents take full responsibility.

“We had been so preoccupied with many other problems that year that we hadn’t given Jeanette the proper attention. She was surrounded at home by illness and a depressing atmosphere. On the way back from Reno, she realized what she had done. She came straight to us, and it was all over very quickly. We went over to the boy’s parents’ home together, and we had the marriage immediately annulled.”

These are wartime years. “The Hut-Sut Song” is sweeping the country, and some of your father’s best automobile customers, the cadets stationed nearby, are constantly banging it on your family piano at home. You’re the little sister to them. They nickname you “Double Bubble,” and they saturate you with your favorite bubble gum. Some of these boys go in with General Doolittle on that first raid over Tokyo, and won’t be coming home. . . .

Your dad takes a job as chief outfitter for a shipyard. Your mother works there as journeyman electrician. And you are working at Bravo & McKeegan’s men’s clothing store in Stockton for fifty cents an hour, remember?

“I loved working in the men’s clothing store. We had the biggest Army stock in town, and the V-cadets really used to flock in there. When the regular cashier went on vacation, I got to work with the business end of it, and then I had a ball I loved working with figures. There was one bad evening, however, which I’ll never forget. The cash register was ten dollars short, and we stayed there until late at night trying to find the mistake. It turned out that it just hadn’t been rung up properly, but I was sick.

In 1943 you’re sixteen years old, and a popular co-ed at the College of the Pacific in your home town. And these are golden days to be always remembered. Football games. The annual Mardi Gras. Pledging Alpha Theta Tau sorority. You sing with the A Capella Choir, and your clear voice floats with the others out the open windows and across the campus to the strains of “Come to the Fair” and the school song, “Pacific, Hail.” You get the second lead in “The Pirates of Penzance,” your one stage experience. Music you love, but you hate speech class. Ironically enough, in speech class you feel self-conscious and inadequate.

You’ve given up your high-school dream of being an algebra teacher by now, and you’re undecided about your major until the choir sings at the state insane asylum. You’re profoundly affected by the whole world of the living dead. But you notice, when the choir sings, that music seems to be a happy medicine for the inmates. Some of them seem more cheerful and relaxed. And you decide to major in musical therapy.

You cannot know now, Jeanette Morrison, that Fate is already readying a far larger audience for you. Your star will twinkle high in the Hollywood Heavens and you will touch the lives of millions with another form of “happy music” you make. . . .

In 1944 you form college friendships that will last through the years. Two of the sorority sisters who stand joined with you in a circle in the candlelight at meetings are your lifetime Stockton friends, Marie and Helen Arbios. Marie, today Mrs. Frank Boyle, wife of the coach of Stockton College, recalls a few college capers you two shared:

“Quite a few, as I remember. Jeanette was very popular in school, as sweet as she was pretty, and never conscious of her good looks at all. The kids all loved her. We used to double-date a lot. Ball games, school dances, and affairs like the annual college Mardi Gras. Sometimes we would go dinner-dancing at the Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Francisco or to the Claremont in Berkeley when our team played Cal’s. After one game we all had dates with some Merchant Marine officers and we went out on the town. Jeanette had a new hat with a veil studded with rhinestones. We all thought it was so dreamy. Today she screams whenever she sees a picture that was taken that night.”

In 1944, too, first love blooms for you. You meet Stan Reames, who’s in school studying under the Navy’s V-12 program, and yours is a typical college romance. On October 6, 1945, you’re married in the campus chapel, with Marie and Helen Arbios, Margaret Shepherd as bridesmaids. Your parents leave Stockton to work at a swank winter resort and give you the use of their duplex and all the new furniture for a wedding gift. You eke out a serviceman’s allotment by keeping two students who room and board with you. Stan Reames has the big dream of someday going to Hollywood and starting his own sixteen-piece band. . . .

But Fate is already moving in with her own idea of a future for you—

For Christmas 1945 your parents gift you with a holiday vacation at the Sugar Bowl Ski Lodge, near Soda Springs, California, where your father is employed as assistant manager and your mother as receptionist.

Vacationing at the Lodge, too, is George Dondero, San Francisco businessman and amateur photographer. He shoots various winter scenes around the Sugar Bowl, and of the guests skiing there. Your parents mount the photogs in an album in the lobby. And you, too, Jeanette Morrison, pose for a ski shot for him.

You’ve returned to college when Norma Shearer and her husband, Marty Arrouge, arrive at the resort. Turning the pages of the album in the lobby one fateful day, she’s stopped by two pictures of a fresh-faced co-ed and her vivid radiance. That night your parents place a long-distance phone call, but only you know just how excited and startled you are:

“Startled! I remember saying, ‘Oh, no— Not me! How could I? I’ve never even acted. Oh, no—not me. . . .’ I was so afraid Miss Shearer might think I was an actress—and I wasn’t. ‘Are you sure she knows I’ve never done anything?’ I kept saying. I wanted to make sure it was very clear I knew from nothing about nothing. . . .”

Your parents arrange for you to come back to the Lodge, but on Saturday before you arrive Norma Shearer receives a message saying her son is ill, and she’s flying to Los Angeles even as you are bus-bound for the Sugar Bowl. When weeks follow, and you hear nothing further, you’re not surprised. What would you have to offer to the movies?

In the spring—1946—you accompany your husband and sixteen musicians to Hollywood to help Stan realize his dream of building a fabulous band. You’ve borrowed money. You’ve sold your car and anything else that’s salable to get the stake that will start the new band to fame. All of you move into cheap quarters at the Harvey Hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard. But fifty dollars weekly for each musician, recordings, rentals for rehearsal studios soon eat up your stake. There are no bookings. You’re broke, disillusioned and wondering what the next move can be, when Fate in the form of a forwarded letter finally catches up with you . . .

And here, for the first time, the star who discovered you and who’s responsible for that letter, Norma Shearer, tells the whole story behind two photographs—and what she saw in those photographs that is to change Jeanette Morrison into a Cinderella star the whole world will soon know as the screen actress Janet Leigh:

“Marty and I were at the Sugar Bowl, skiing, and one day I was looking through the album in the lobby at pictures of various people at the resort. Among them were two lovely photographs of a girl I didn’t know. She wore no make-up. She had long naturally brown hair, wonderful feathery eyebrows, and there was a soft warm breeze in her face. ‘Who is this lovely girl?’ I asked. “That’s my daughter, the receptionist said. I asked if I might have a copy of the picture. “You may have these,’ she said, and took them out of the album for me.

“I saw in her face an ethereal quality, an elusive aesthetic quality, an emotional quality which I thought was actress material. It seemed to me everybody they were putting in pictures then was trying to be sexy and cute. I thought there was a place on the screen for a face with a quality like this.

“I took the pictures with me when I left the Lodge. If ever the right opportunity presented itself, I knew I’d like to do something about Jeanette Morrison. Not to help Jeanette Morrison, but to help my studio, Metro. However, in the process of getting settled again when we got back to town I was busy, and nothing happened for some time.

“Then David Lewis was going to produce ‘Arch of Triumph,’ and he was looking for someone to play the part of the girl. In the book she was a fragile young girl who dies of cancer. He was trying to talk me into playing the part. ‘Oh, no, I wouldn’t be right for it,’ I said. ‘But there is a girl—a new girl—who would be great in this.’ We agreed to meet, and I would bring the photographs.

“Marty and I met David at Romanoff’s late one afternoon and we talked. But when he rushed off to a preview later on, he left the pictures behind. We were meeting Benny Thau and Eddie Mannix from Metro, and Lew Wasserman, of MCA, there for dinner, and when they came in, I asked, ‘Anybody want to see a lovely face?’ I passed the pictures around the table. My friends from Metro thought she was a lovely girl—and that was sort of that. But Mr. Wasserman was the smart one. ‘May I have these?’ he asked. ‘Certainly,’ I said. ‘Her name is on the back. I’m not sure where you will find her, but her parents are at the Sugar Bowl Lodge.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll find her,’ and took the photographs. A week later he called me. ‘I’ve got your girl placed,’ he said. ‘Where?’ I asked. And he said, ‘At Metro.’ Which I thought was ironic, remembering how Mr. Lewis had gone off and left her pictures lying there.

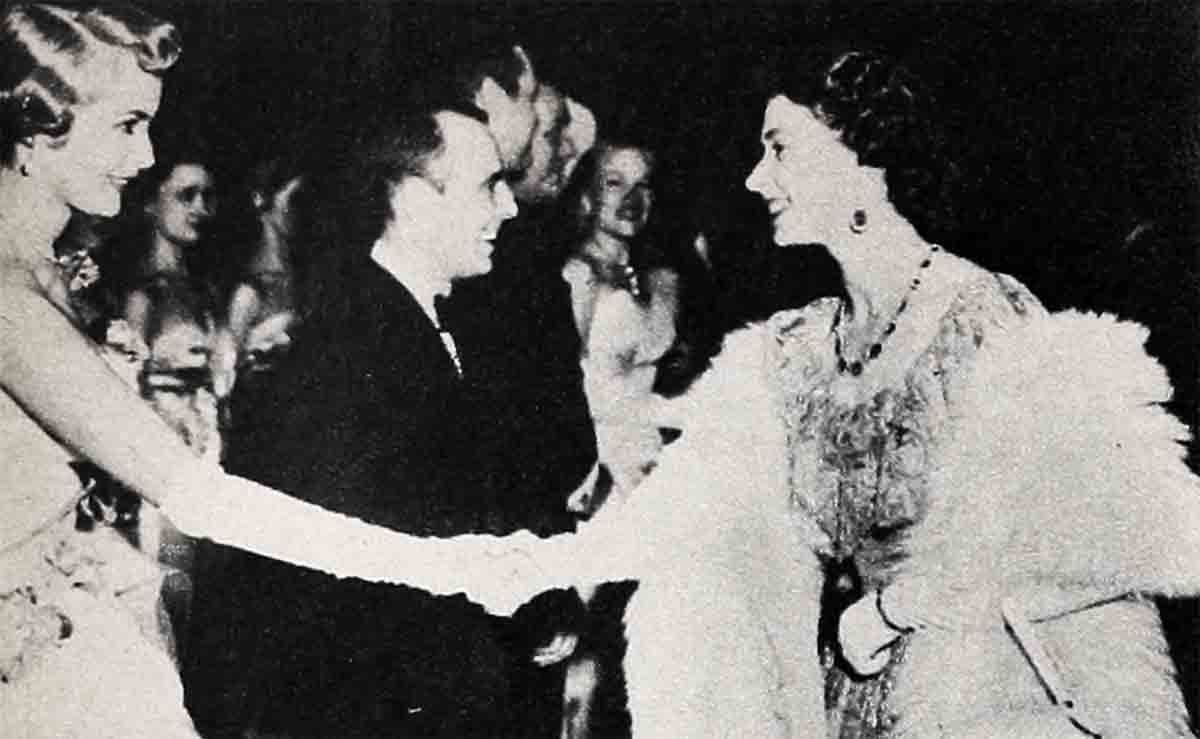

“Not too long after this someone from the M-G-M publicity department called me. ‘Your girl has the lead with Van Johnson in “The Romance of Rosy Ridge,” ’ he said. ‘Will you come out and have your picture taken with her and with Van?’ I told him I’d love to come meet her. ‘Meet her! I thought she was your protegee,’ he said. I’m sure he thought she was a distant relative—a cousin or something.

“I met her and we had a picture taken. Gone were the feathery eyebrows, and her wavy hair was trained to do what it was born to do. But more than that, there was an expression of gratitude on her face, I shall never forget.”

Nice words, these. But in June 1946—broke and discouraged and wondering how to meet the next week’s rent in a Hollywood hotel—you’re surprised to find anybody thinks you’re capable of a career or any kind. With excited widening eyes, you read the letter that’s been forwarded to you. And by the way, what does the letter say?

“It was from MCA. They wanted to know whether I was ‘planning to be in the vicinity of Hollywood or Los Angeles in the near future.’ And if not, would I ‘consider making a special trip down’ that summer? I called them immediately and told them I was already in their vicinity. I was so excited. For my interview at the agency the next day, I put on my best Stockton dress—a rose wrap-around crepe—which was pretty bad. I wore lush purple flowers in my hair and purple gloves. And that isn’t all. Can you take more? When I went through the lobby of the hotel, all the boys in the band chorused, ‘You look so beautiful!’ But when I got out to MCA I wish you could have heard Levis Greene trying to tell me tactfully to please somehow look like I did in the pictures when we went out to M-G-M.

“My mother sent me a birthday check and I bought a perfectly plain pink cotton dress trimmed with black rick-rack braid and I wore that. At the studio, Lucille Ryman, head of the talent department, said, ‘Stand up,’ and I stood up. She asked me if I’d had any experience acting and I said I had not. I wasn’t in there five minutes, and they signed me to a seven-year-contract! Then Lillian Burns, the studio drama coach, gave me a scene. ‘Work on it, she said. I didn’t know what to do with it, so I just memorized it. This woman—Lillian Burns—was like my Guardian Angel from the first time I read for her.”

And with reason. Take Lillian Burns’ word for it:

“She came in with that magnificent long hair of hers, with stars in her eyes and with that same enthusiasm she has today. I’ve never met anyone who had real stars in her eyes like this girl had. It was such a refreshing thing, just to look at her. She had such warmth and excitement about her and that feeling of being so alive and enjoying everything. I gave her a scene from ‘Random Harvest,’ a very difficult scene. And I was amazed at her reading. She had natural talent. She had no conception of the acting craft—but she had a wonderful instinctive quality we don’t find too often in people who’ve never acted before. I was terribly excited about her, but I wanted to be certain her first reading wasn’t a fluke. By the third day I was convinced the quality was really there, that she had a real basic instinct for acting, as well as the ability to listen, to respond and to project. All this and that wonderful face. I recommended the studio not wait three months until they made the test—but to take up Jeanette Morrison’s option immediately and get to work with her under her regular contract.”

So, Cinderella, your foot is inside the magic kingdom. You’ve signed with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for $50 a week. True, the fifty dollars doesn’t stretch too far. You and Stan take a little room in the backyard of your uncle’s house in Glendale, and you ride the bus from Glendale to Culver City—two hours—every day. But the stars are even bigger in your eyes. And within those magic walls for you it’s Christmas every day.

What you don’t know, Janet Leigh, is but for Fate—you could have been finished before you even started. A wave of retrenchment has started at the studio. Many young players who are not working before the cameras are let go. But your Fate—whether in the form of a “lucky” pink cotton dress or a snapshot in borrowed ski pants—knows no obstacles. And Destiny doesn’t desert you now.

Going into production is “The Romance of Rosy Ridge,” starring Van Johnson, the rave of the bobby-soxers now. The girl, a name actress, has already been cast and her wardrobe already fitted. But director Roy Rowland and producer Jack Cummings are not satisfied. She doesn’t have the special quality needed for this girl.

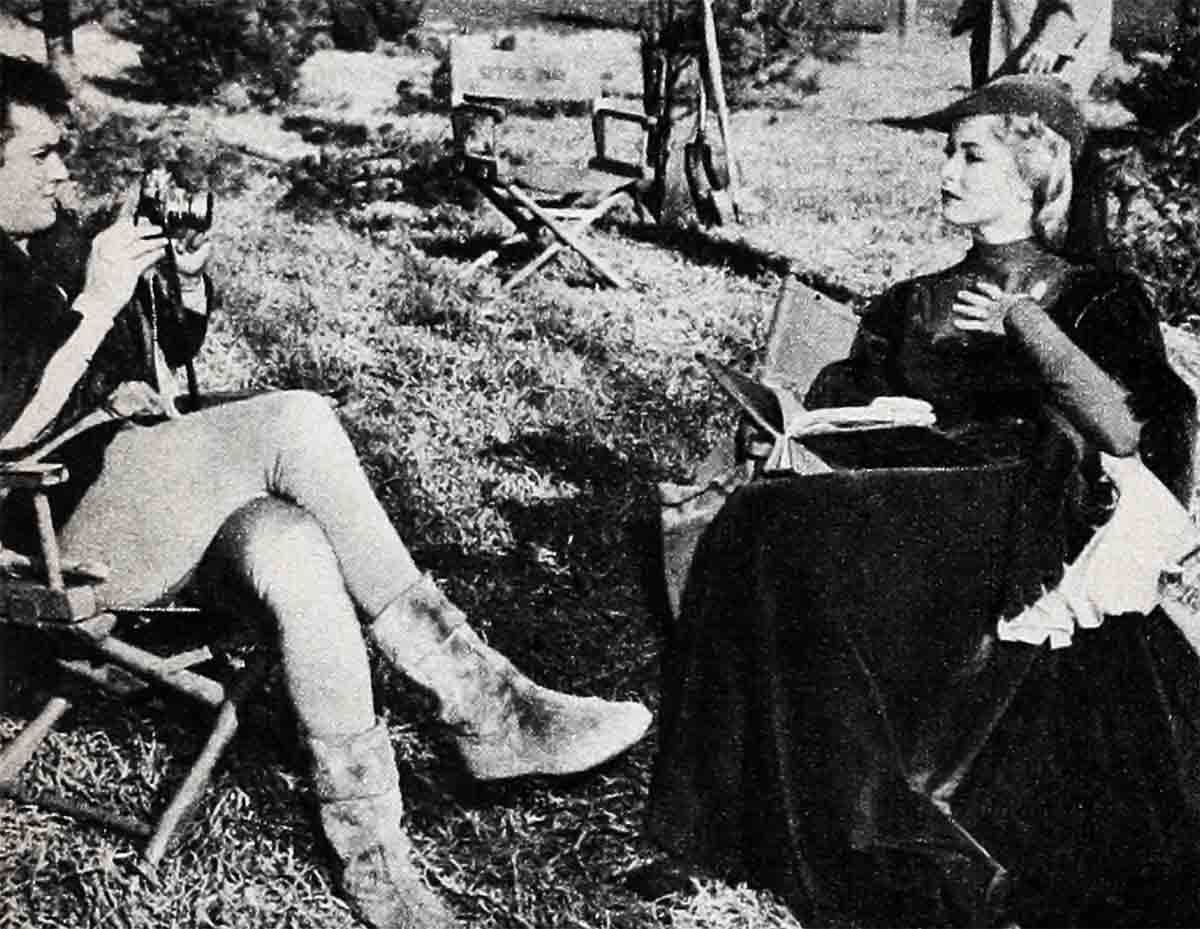

One Saturday, Stockton’s favorite daughter is at the studio plugging eagerly away. Strangely enough, both the director and the producer, who seldom come in on Saturday, are also there today. The three of you meet . . . and a new star is born. According to director Roy Rowland:

“Lucille Ryman called me and said she wanted me to meet somebody. ‘This girl has never done a part before. But she’s been signed by the studio and I want to know what you think of her,’ she said. What I thought was that Jeanette Morrison was the girl I must have for ‘The Romance of Rosy Ridge.’ She had an exquisite sensitive face, the dewy unsophisticated quality we needed for this girl. I took her to Jack Cummings, and he enthusiastically agreed. ‘I want to make a test of this girl,’ I said. To Jeanette Morrison I said, ‘I want you to do everything I tell you to do,” and she did. And more. She responded as though she knew, too, just how much this test meant to me. I stayed late at the studio cutting the test —and I was sure she was our girl. There was still one more thing. I didn’t know how Van Johnson would feel about an unknown girl playing opposite him. Van was our big boxoffice star, but he was still fairly new, too. The girl’s part was just about as important as his, and he might insist on a name star. I told him I’d like him to see a test a girl named Jeanette Morrison had made. “She’s never done anything, but I want you to see her,” I said. And Van, well Van thought she was great. He said—and I’ll never forget this—“Somebody had to give me a break, and I’m glad to be able to pass it on.”

Through all of this you are walking on wings. You cannot know all the action going on behind the scene that’s deciding your distiny, can you, Janet Leigh?

“I didn’t know anything about anything. I didn’t know what to do when I got before the camera. All I knew was that I loved the feeling of being someone else. And for some strange reason I wasn’t too scared. It was all a lot of fun and a wonderfully exciting experience. One week after the picture started I knew this was what I wanted. Suddenly I knew I loved this world. I couldn’t understand why I’d never wanted to be in it before. It was something lying there dormant—somebody opened Pandora’s Box and there it was. I was nervous in the love scenes with Van. But Van was so wonderful to me. From the first day he was always there.

“I’ll never forget my first premiere. We got there just after Van arrived. I had on a beautiful dress I’d borrowed from the studio. Nobody knew me from beans and I was just thrilled being there. All the photographers were crowded around Van. Suddenly he came over to me and kissed me, and they started popping away. I knew he did it just to get attention for me, which was pretty wonderful!”

At the preview of “The Romance of Rosy Ridge” they think you’re pretty wonderful, too. Your name is on all lips, and all eyes are centered on your excited face. All there know—with your first picture—a new and exciting star has been born. If there’s any doubt about it, your second, “If Winter Comes,” with Walter Pidgeon and Deborah Kerr, cinches it.

All Hollywood acclaims you affectionately their own Cinderella Girl—and your own grateful star twinkles brighter every year. . . .

In 1948 you are marching triumphantly across the screen, carrying your scepter high. You portray Mrs. Richard Rodgers in “Words and Music.” You play your first dramatic role in “Act of Violence,” with Van Heflin. You’re Meg in “Little Women.”

This is the year, too, your college marriage dissolves, and amicably.

In 1950 you return to Stockton, California—a star. You’re heart is full when your home town honors you with a “Janet Leigh Day,” and your throat is as full as it used to be in speech class when you could find nothing to say.

One fateful evening in 1950, like any deserving “Cinderella” you meet your prince. At a party in Lucey’s Restaurant in Hollywood you meet Universal-International’s Anthony Curtis, who’s stolen the hearts of girls across the nation with his first starrer, “The Prince Who Was a Thief.” You were to be no exception. And he falls for you, too, with his whole uninhibited heart. In Tony’s words:

“Janie was the movie star, the girl next door, the girl I loved, and the girl I wanted to spend my life with. She was the whole and entire cast. When we were separated a little while—when she went to Pittsburgh and I was on tour in Chicago—I really realized how much I missed her. How much a part of my life she had already become. I shopped for her ring in Chicago, and fortunately I had my measuring stick along, having carried it in my wallet for quite some time. Once, in Hollywood, I’d broken a match and tried it around her finger, and I’d marked where it fit on mine. The jeweler thought I was a little crazy. ‘What’s the ring size?’ he said. ‘Second wrinkle past my knuckle,’ I said. We kept measuring the match stick around. He thought it was a wrinkle less, but I was right—and the ring fit Janet’s finger perfectly.”

Yes, the ring fits. . . .

On June 4, 1951—in the face of all the depressing prophets who warned both of you that marriage can destroy your careers and dethrone you with your legion of teenaged subjects—you are married in the Pickwick Arms Hotel, Greenwich, Connecticut, and Jerry and Patti Lewis are standing by.

Together, you and Tony proved the prophets are wrong, and you’re double stars zoom.

In 1953, Janet Leigh, your happiness is brimming over. You walk out of the office of your long-time physician, Dr. Sarah Pearl, with shining eyes and wings on your heels, your final wish is fulfilled. . . .

But on July 9, 1953, tragedy strikes, and this happy fulfillment is postponed. Dr. Sarah Pearl is in St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, a patient there, when the phone rings beside her bed.

“I’d been in the hospital for a month, but I kept in daily touch with Janet. I was in traction for a spinal disc with twenty pounds tying me up, when Janet called this time. She was a sick girl. I knew I couldn’t be any help to Janet in traction. I opened my braces and got out of bed. When I started getting into my white trousers for surgery, the nurses really thought I was out of my mind, but I’d been looking after Janet when she was first signed by M-G-M and nothing would stop me from helping her when she needed me. When Janet came out of surgery she said, ‘Doc—does this mean? . . .’ And I told her, ‘You can’t have this baby, but you can have another baby.’ She was very brave—she took it right on the chin.”

Life has schooled you for this, too, Janet Leigh. Taking it on the chin. But in 1954 this is your life. . . .

Your star is twinkling brighter than ever in the Hollywood heavens. You starred in twenty-eight pictures, in the eight years since you and your “lucky” pink dress went through those magic gates of M-G-M. Today you have a fabulous new contract, shared by Columbia and Universal-International, and you’re presently starring in Columbia’s sparkling musical, “My Sister Eileen.”

You’re happily married to the public’s own prince of hearts—and you share him with a few millions of them. Yours, too, is a vast kingdom of loyal subjects throughout the land. Your love story has captured the hearts of fans everywhere. And although Hell’s Kitchen is a long way from California, Tony Curtis is convinced if Hollywood hadn’t arranged it, fate would have led him to you.

“I would have found some reason to go to Stockton, California—even if to sell neckties. I would have found her somewhere—some way—some day.”

But fate willed you to shine in the sun, Jeanette Morrison, and today you’re the shining inspiration for every small-town girl who hopes, and prays, life’s big parade, with all it’s romance and adventure, won’t pass her by.

And you, Janet, will play an even greater part in the adventure ahead. For you are destiny’s daughter—and you’re in devoted hands.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955