Two Women And A Dream—Betty Grable & Joan Crawford

In the hot noonday sun of a sweltering midwestern summer, Billie Cassin rested against the wooden steps of her house and let the garden hose cool her feet.

She was caught in a dream. A dream in which she was dancing in front of a red velvet curtain on a red velvet stage—the greatest dancer in the world. In the audience sat a prince. Now he stood, now he bowed, now he asked her to marry him. And as six-year-old Billie had done many times before, she refused. She wasn’t quite sure why. It had something to do with too much to do, too much to see and, somehow, a prince was not quite enough for her. There was a yearning in her that a prince couldn’t satisfy.

She, shook her head at the thought. Then standing up, she ran across the wet lawn. Suddenly, screaming in pain, she collapsed. She’d stepped on a broken bottle, cut a vein. Her foot was covered with blood. Before she could cry, the world wavered in front of her. She was found ten minutes later, soaked in blood, and taken to the hospital. When she awoke, she was in the operating room. Starting to speak, she was silenced by an ether cone pressed against her face. She tried to scream, but the cone was held tighter and tighter until terror and fear turned into blackness. Her last conscious thought was that she was now dead. For Billie Cassin—for Joan Crawford—childhood was over.

Several years later, a few hundred miles to the northeast, another six-year-old child sat in the noonday sun of a hot midwestern summer. Her dreams were of a horse she would someday own and the name she would give it.

A little later. when there were shadows on the sidewalk, she galloped down the street, hitting herself occasionally with a penny licorice whip and shouting, “Go Pinto, go Thunder.”

Two children living a few hundred miles apart, feeling the same heat, seeing the same fields of rising wheat, born into the middle strata of the American middle class, each the younger of two children, each destined for a similar career.

But because people differ from the moment of their birth, they can grow up in the same state, in the same city, and their lives will differ. They will need different things and want different things and their lives will grow apart to get them.

At the Cassin home, there were arguments. Mr. Cassin left one night. When Billie woke in the morning, he was gone. Billie, her mother and her brother moved to the lower fringes of a middle-class section. Mrs. Cassin no longer sang, her face took on a harsh, strained look put on by many problems. Mrs. Cassin operated a laundry, and Billie took her baths in a laundry tub. She slept in a room above the laundry where the smell of freshly pressed sheets was the last thing she remembered before dropping off to sleep. Sometimes she cried herself to sleep because she still limped and might never be able to dance. But no one knew that—Mother had no time.

Con Grable moved in the other direction. He was a bookkeeper who became a stockbroker and moved his family to a big hotel where Betty roller-skated down the halls and worked the elevator by herself and grew up in the sun. She rarely cried. There was no need to.

Ambitious, shy, angry Billie Cassin— sure of what she wanted but bewildered about how to get it—spent one year behind the big iron gates of a private school, St. Agnes Academy in Kansas City, Missouri. She was partly student, partly waitress, and at night she would stand with her face pressed against the gates, wondering how she could get out. So young, and yet she had already learned one lesson—anything she wanted she would have to get for herself.

After a while, she invented a world that was more to her liking than the real world, a world that ended with a walk down a lovely country road in the green of spring with a man—who was still faceless—by her side.

As someone was to say of her many years later in Hollywood, “For Joan the make-believe world is real—the world of movies and of the characters she plays. Hiding behind a character for her is the real truth. I think she learned the knack long ago to cover up her shyness. Even between pictures she creates a make-believe world.”

It was true of her even at fifteen. She had a need for a make-believe world. So she ran away to Chicago and a twenty-five-dollar a week night-club job.

“I can dance,” she told the owner of the club.

“Well . . .” he paused hesitantly.

She stood in front of him, with a determined chin, pretending a sureness she did not feel. “I can dance. I can dance better than anyone you’ve got.”

She was hired.

Back in Kansas City, Mrs. Cassin was confused and shocked. She was not equipped to handle a daughter who aspired to be the best dancer in the world. For better or for worse, Billie Cassin was on her own.

In St. Louis, Missouri, Betty Grable also went to a private school—Mary Institute. She liked life there as well as she liked anything, including horseback riding. And she was well-liked, too.

Both she and her sister Marjorie were beautiful, but Marjorie had—from the beginning—a stubborn streak that Betty didn’t have. Mrs. Grable, unlike Mrs. Cassin, understood a girl’s desire to be a star. She had had it herself and had transferred her yearnings to her daughters. Marjorie smiled and refused to take lessons. But Betty, younger and better able to be bribed, listened to her mother.

One dancing lesson was traded for an hour’s ride on Sunday; one singing lesson was traded for the right to appear with her drill team in a horse show. Most of the time her drill team won, and the lessons did not seem to Betty to be too high a price to pay for that glory.

Unlike Billie Cassin, she was not ambitious. Perhaps she didn’t need to be. She was often described as lazy. Luckily for her future, she had a mother who would see to it that she did something about her vague desire to dance and sing.

Many years later in Hollywood, of Betty it would be said, “She’s a straight shooter, no make-believe, no pretense about her. As big a star as she is, she never demands a thing. Once I was handling an interview for her,” explained a studio executive. “I left the room on other business, and the reporter stayed three hours. Any other star would have gotten raving mad and gone to the front office. Betty just asked please not to let it happen again.”

In all her childhood, there was only one thing she wanted and did not get—a horse.

“Daddy bought me a saddle once,” she has said, “but the horse never came. A saddle was useless without a horse, so I made him take it back.”

When Betty was thirteen, her mother decided she was ready. They came to California. Her mother was with her constantly: teaching, exhorting. When Betty’s first chance for a specialty number came, she slipped on the steep movie steps. She picked herself up, crying.

“Do it again,” Mrs. Grable whispered.

Betty went back to the top of the stairs again. She slipped for the second time. She ran to the side of the stage, and Mrs. Grable followed her.

“Go back,” she said. “Do it again.”

“No,” Betty said, rubbing her back.

“Look at me,” Mrs. Grable said. “You won’t slip again. Go back.”

Betty Grable went to the top of the stairs for the third time and danced down them.

The studio let her—and a dozen other chorus girls—out a few months later, and Mrs. Grable decided they should go to New York.

“I’m not ready,” Betty said. “I’m not ready at all.”

“Of course you’re ready, darling,” Mrs. Grable said. And the packing began.

In the meantime, Billie Cassin had already danced her way through New York. But she had had no protection from the night-club wolves except the protection she could make for herself. She was toughen- ing up—at least on the outside—and making her own decisions. When an offer came from M-G-M, there was no one to ask what to do. She accepted, went to California, had her name changed to Joan Crawford in a contest, danced in several movies and fell in love.

The man she fell in love with was Douglas Fairbanks, jr., prince of Hollywood, son of its king and stepson of its queen.

Joan Crawford and Douglas Fairbanks, jr., were young and in love. They walked the beach at night, threw baseballs at concessions on the amusement pier and ate candy apples. They invented a private language so that they could talk to each other in crowded rooms. Joan was overwhelmingly happy.

Joan Crawford has since said, “With Douglas I was young for the first time. My childhood had ended so early, almost before it began, and when I married Douglas I found it again. We sat on curbs and laughed at senseless things and rode roller coasters at the beach and loved each other with all the intensity of the young.”

But nothing had come very easily to Billie Cassin and a happy marriage did not come easily either.

Before her marriage she had bought a house.

Douglas laughed and looked at it and asked, “Why so big a house? For our twelve kids?”

She was not quite able to explain that she needed something securely fastened to the ground for security, the emotional security that had been missing most of her life. She has the house still.

At the first party given in their honor after their marriage, Joan attacked the seafood cocktail with a large and cumbersome fork. When she saw her mistake, she put the fork down quickly—and someone laughed. Joan ran from the room; Douglas found her in the hall.

“It’s all right, honey,” he said. “It’s all right.”

“It isn’t all right,” she said. And there were no tears on her cheeks. “I won’t make the same mistake again.”

If you are deprived of something when you are very young, you sometimes want it out of all proportion to its importance. Joan is this way about learning—all kinds of learning. She has had to grab these things herself, to fight for them and fight to hold them. She has wanted to learn everything—how to walk, how to dress, who Aristotle was, what fork to use at a formal dinner, the proper way to address a Duke. She’s learned all these things through the years—and more, much more. Because of this, people have called her a social climber, a few more names.

She pretended not to hear. Sensitive people sometimes build heavily armored walls about themselves and look out on the world from tiny slits in the top of the wall. The world sees only a determined chin, a diamond-hard exterior. It doesn’t know of the soft and helpless soul underneath.

Joan Crawford is one of these people, and it has always been important to her what people think. That is why the lack of recognition by Douglas’ stepmother, Mary Pickford, hurt her so deeply and injured her marriage so much.

“How do you do?” Miss Pickford said when they were first introduced. And Joan’s audience with the queen was at an end.

This, too much youth, two careers and Joan’s own fierce striving for perfection, for knowledge, were too much. Four years after their marriage, Doug and Joan were divorced.

Betty Grable’s first marriage also ended in failure. She had returned to Hollywood, played the cheerleader of Wabash U. in a dozen college pictures and married Jackie Coogan. He was the first boy that she had ever seriously dated and she had never given herself a chance to find out about others. But she is not the kind of person to be divorced even once. She is too relaxed too content with life in general, too easy to live with. And the marriage might have lasted if it had not been for Jackie’s tremendous personal problems. Betty learned from experience and decided not to make the same mistake again. When the next time came, she didn’t.

Joan Crawford was not so lucky. Even before Betty Grable’s first marriage ended, Joan had reached again for love. This was her “great love,” another man from whom she could learn, another man who was above her, she thought. in charm and grace and wit and knowledge and acting ability—Franchot Tone. Hollywood had brought him from the stage to act and then encased him in a series of sophisticated playboy roles.

Joan Crawford was still reaching and, in her marriage to Tone, she learned. She learned what words like “expeditious,” “juxtaposition” and “montage” meant. She found there could be pain in learning. Franchot was a member of the Group Theatre, a brilliant gathering of serious actors and directors.

“The only time,” Joan has said, “that I didn’t want to be a movie star was the first night I had the Group Theatre for dinner.”

She had spent all day working on hors d’oeuvres and setting the tables by the swimming pool. When the guests arrived they didn’t ignore her, they were very kind. But she was lost by their talk, and so angry with herself for her lack of knowledge, she felt like throwing the whole dinner into the pool.

After they left, she turned to her husband and again there were no tears on her cheeks. “The next time they come,” she said, “I’ll be able to talk to them. I will.” She took books from the library. And the next time they came, she was.

The little dancing girl learned. She turned herself into an actress and a popular one. In 1937 she was top woman on the annual poll of money-making boxoffice personalities. In 1938, she was still there, but Tone wasn’t. Saddled with parts that gave him no chance to act, he was at first frustrated, then angry, finally enraged. And there were no children to help hold the marriage together. Joan had had two miscarriages. She and Franchot looked into adoption agencies, but before they could adopt a child, their marriage ended.

Two years later, Joan was in Franchot’s place—with a vengeance. For ten years she had been playing the rich girl who marries the poor boy or the poor girl who marries the rich boy. Suddenly the public discovered it didn’t care one bit.

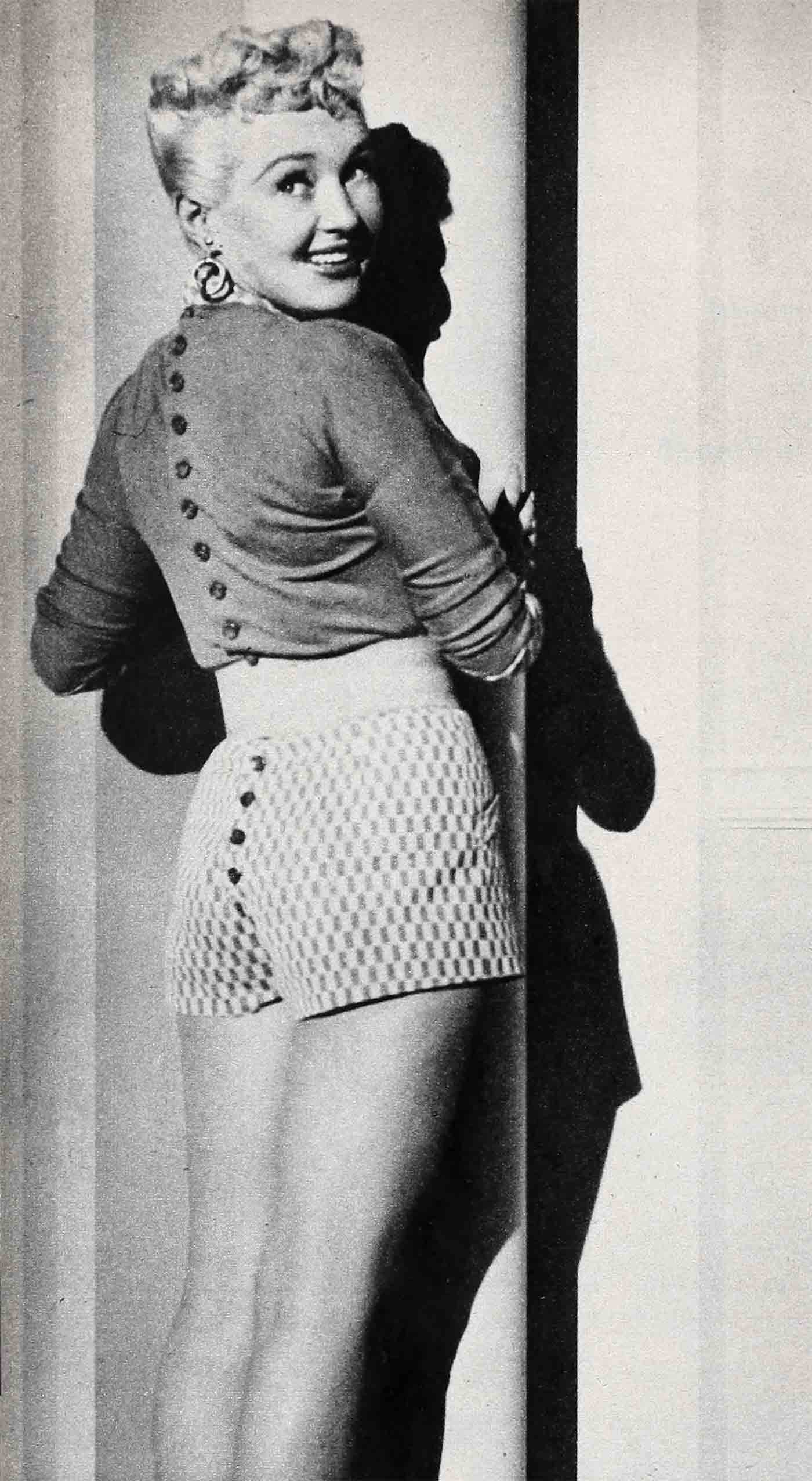

At the same time, Betty Grable was becoming an American institution. Five million pictures of her were hammered into the barracks walls of the Aleutians, pasted against the bulkheads of aircraft carriers, carried in the pockets of a million American soldiers through the mud of Okinawa and New Guinea. Airplanes were named after her, generals waited in line to meet her, the American public made her the top boxoffice personality of 1943 and 1944.

And she took her new fame with the same calmness she had taken the years of being a nonentity. There was no pretense about Betty.

“There’s a wonderful new art exhibit in town, Miss Grable,” a society matron said to her once. “I have a private card for tonight, and it’s something you really must see.”

“I’m sorry,” Betty said. “But I’ve got a date to play cards with my hairdresser and her husband.”

She attributed her sudden fame to luck and got violently angry at people who prostrated themselves at her feet and called her Miss Grable. She did not go to more operas or concerts or art exhibitions, because operas and concerts and art exhibitions did not intensely interest her. And she refused to pretend an interest she didn’t have.

And she fell in love. You can call her happy marriage luck if you like, because neither she nor Harry worked at being happy together, but it wasn’t all luck. She had learned, too. She had learned from her first marriage that any little faults you find should be left below the surface, where they would not disturb the calm flow of the years.

“I met Harry James,” she says, “at the Hollywood Canteen. We were both entertaining the soldiers—but on different nights. I loved his music, so I had my night changed to his. After the show, I asked him to drive me home.”

Betty knew what she wanted when she saw it. They had a hamburger at a drive-in, three more dates, and the fourth day he left for Chicago. Every night for the next eight weeks, they spoke on the telephone. He asked her to meet him in Las Vegas. He would slip off his train and they could be married. She agreed.

Only fragments of the weekend can she remember now. “His train was late and, by the time it arrived, there was such a pile of cigarette stubs in the car, he could hardly push his way in. We ran to meet each other, and he tripped over a chain and all his suitcases slid around the station floor. When we got to the hotel, the minister was in the hall, rehearsing his speech. He was terribly guilty when we caught him at it.”

“Do you want the three-minute ceremony or the five-minute ceremony?” he asked.

“Three-minute,” they said together. A three-minute ceremony can be more binding than a formal wedding in a church.

After her marriage, Betty continued enjoying the same things she had enjoyed all her life. Neither she nor Harry tried to change or improve one another. Another couple who had married after four dates might not have had a lasting marriage. But here were two people who were al- most too lazy to argue and too well matched to need to. But Betty was not a perfectionist—she never worried about little flaws.

From the beginning it was decided that Harry was to be boss. Betty’s unbelievable success was not to be carried beyond the studio gates.

“In the home, it should be the man who dominates,” she said. And in the same breath, “I never bring my work home. It wouldn’t be fair. Evenings are for relaxing and having fun.”

People are built differently, and Joan Crawford could never have made that statement. She cannot make the tenseness of a long day’s shooting drop from her as she passes the. studio gates. Because of this, she even sleeps in her dressing room when she is on a picture. She does believe a man should be ruler of his home, but she knows that she would try to dominate him. But her ideal man would not permit himself to be dominated.

After her marriage to Franchot Tone ended, she adopted the children they had wanted to adopt together and, later—partly to give the children a father—she married Philip Terry. Terry is a man of whom she says:

“I owe him an apology. I have always owed Phil an apology. I married him mostly because I was lonely, and I couldn’t repay his love with love.”

Those years with Philip Terry were the years she spent planting radishes and lettuce and string beans, chopping down eighteen trees for firewood and not making motion pictures. Joan cannot live without working, but she couldn’t work in motion pictures—she was boxoffice poison. Then someone took a chance and there came “Mildred Pierce” and an Academy Award. She does not feel that those waiting years were wasted, because she tries never to waste time, tries to cram into each hour something new or something thought or something learned.

It was a challenge for Crawford to play the plain, tired, embittered mother of an almost-grown daughter, but she has always accepted challenges, no matter how unsure she may feel inside. The challenge just happened to win her the award as best actress of the year.

The next year it was Betty Grable’s turn to face a challenge.

“I’ve got a part,” Darryl Zanuck said to her, “a straight dramatic part, no singing, no dancing, in a picture called ‘The Razor’s Edge.’ It’s a great role for an actress.”

Betty read the script and said, “No.” Trying to explain, she said, “I’m where I want to be now. And I don’t think it’s right for me. I don’t want to crowd my luck too far.”

Anne Baxter took the part and won an Academy Award with it.

And what of those two dreams dreamed out in the noonday sun of a hot midwestern summer?

Betty Grable satisfied hers long ago and went beyond it. On their first wedding anniversary, Harry’s gift was a horse. Her gift to Harry was another horse. They bought a ranch, but it was too big for just two horses. And somehow, since Harry’s father had been a bandmaster of a circus and his mother a bareback rider and since Betty’s dream had been to own a horse, they somehow went into the racing business. Today they own five racers, six brood mares, one two-year-old filly, four yearlings and one foal. One of their horses, James Session, ran in the Kentucky Derby last year.

Betty refuses to do more than two pictures a year now. There are always beds to make at home and wastebaskets to empty, clothes to buy for her two daughters, Vicki and Jessica. She has never been away from them overnight. That is why she has never made a picture in Europe or on location.

“I don’t know if it’s important, but I don’t want to be away from them,” she says.

In the summer there is a seven-week vacation at Del Mar, where they rent a house at the beach. There is time to swim and tan in the mornings. In the afternoons they can watch their horses run. And if there is a problem to be solved, there is always Harry to tell, Harry to get comfort from, and Harry’s arms to take away the occasional loneliness.

Joan’s young dream has not been fulfilled yet and probably never shall be. By its very nature, it is aimed too high. The greatest dancer in the world. Perfection is not easy to grasp. It is inclined to slip away whenever you think you’ve gotten a good hold. Yet in the search you can touch mountaintops, climb high, hold the world in your hands, and climb higher still. That is what Joan Crawford has done.

But there were penalties to this dream, too. As often is, the greater the dream, the harsher the penalties. There was no one to turn to for so long. There were children to raise alone, tensions to be choked back somehow, loneliness to be fought that can’t be assuaged by physical exhaustion. But it was worth it, for it gave her the courage to seek companionship and love again, to give love, to become Mrs. Al Steele.

Two dreams and two people springing from the same midwestern soil.

One earthy and natural, inviting exercise boys to dinner and spending summers sleeping in the sun, content with her luck and her husband and her life, with watching television in the evenings and with contentment itself. And if she were given the years to race over again, she would do the same things with them, even to the first marriage whose failure taught so much.

One flashing through the sun and through the night, sleeping no more than four hours a day, filling the hours with a search for knowledge and for truth, never content but sometimes fiercely happy. And if she were given the years to race over again, she would do the same things with them, even to the pain through which she also learned.

Two dreams and two people.

THE END

—BY ALJEAN MELTSIR

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1955