His Lady Is Lucky—Dewey Martin

“Well, Lucky, this is it!” Dewey Martin said that morning, throwing a kiss to the girl who stood in the door of their cottage at Malibu Beach, waving him off to his first day before the cameras again.

Later, on the sound stage at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer he waited, tense and eager, for the magic bell that would send him back into the Hollywood ring. He hadn’t worked for almost two years. “The Tennessee Champ” is his first film under a fabulous new contract.

This is it, he’d told her. But how well both of them knew now the challenge every year—every day and hour—could bring.

For the virile young actor with the smoky hair and the keen blue eyes and the look of a guy who’ll get whatever he goes after, this was an exciting event. Perhaps, finally, the real break was this new Metro contract. But too many times Dewey Martin had thought he was set—only to find an even tougher time ahead.

“This is it, it’s got to be!” he’d said to the same starry-eyed girl the night after the preview of “The Big Sky.” But it hadn’t been. Ironically! He-was such a smash success he hadn’t worked again. Howard Hawks, his discoverer, busy in Europe, refused to loan him out. “It’s too dangerous to chance following a good one with a bad one. Better to wait,” he told him. Dewey had waited. And waited.

Finally, when his option time neared again, the producer agreed to give him his release if he found greener fields—and M-G-M immediately signed him.

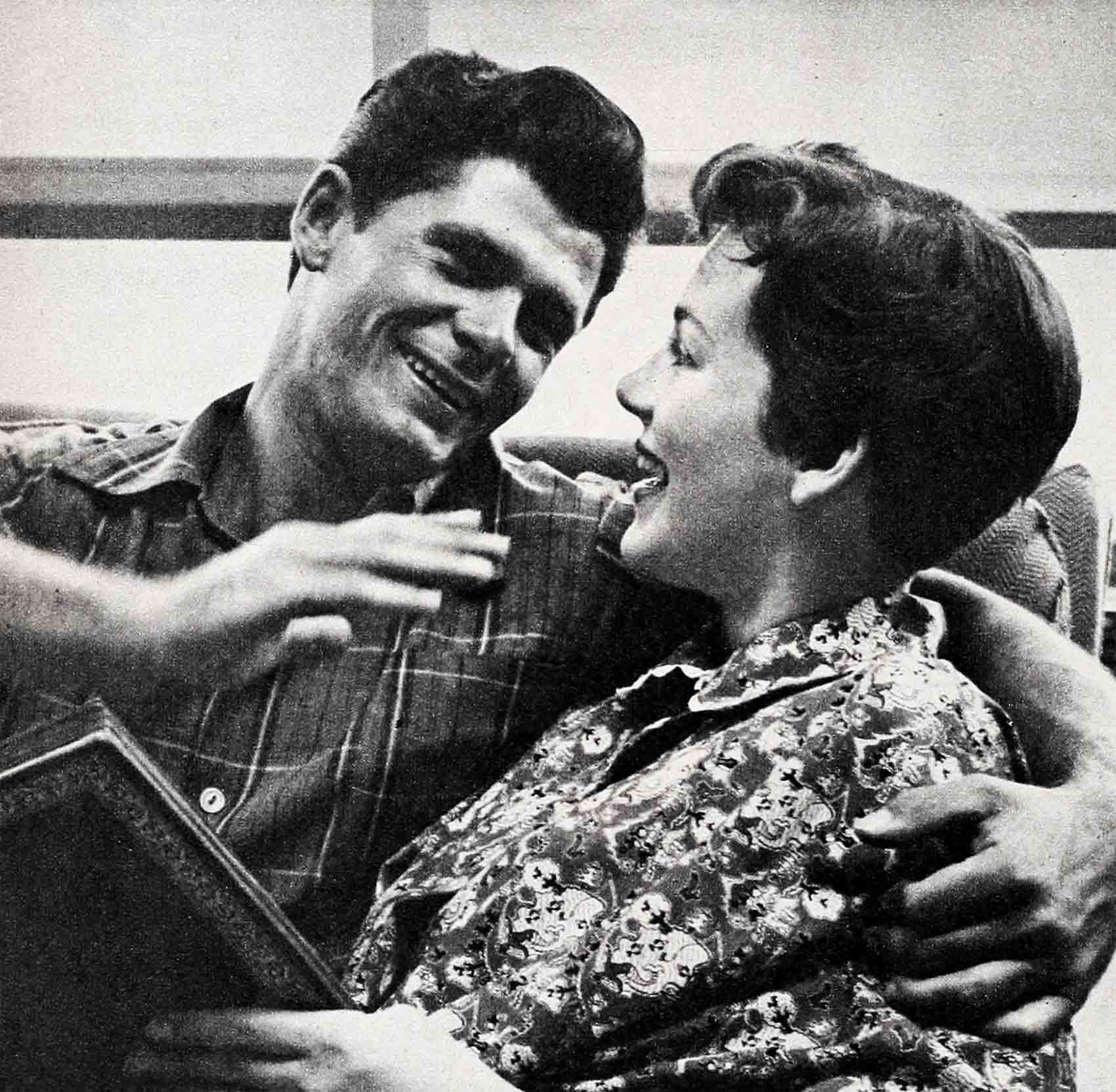

During the long months when the big dream seemed so near and yet so far, Dewey’s fans helped keep up his faith. The greatest strength came from his greatest fan, a plucky girl with a fighting heart.

“Lucky,” he calls her. And lucky she’s been for him. Yet as lucky as their future seems now, they know they must take nothing for granted. Neither success, nor the’ happiness they’ve found together.

This is their story. Dewey and Mardie Martin’s. And even as cameras roll again for him, nothing in any picture will pack more punch and pathos than the story of the kid from Katemcy, Texas, who couldn’t be counted out—and the pert, pretty girl with the red hair and sparkling green eyes. For it is from Lucky that Dewey Martin has learned what the word courage really means.

Struggle, however, was never any stranger to him. Dewey was early acquainted with it when, after. a week’s work in his first movie, “Knock on Any Door,” a talent authority intimated he would go farther back home on the range. Director Nick Ray had called Dewey’s rooming house, furious, when he heard about that. “If anybody tells an actor in my picture he’s no good—it will be me. I’ve seen the rushes, and I’m sure you have a great future,” he told Dewey. The way some people figure, “Hollywood’s like a street fight—if you can sling mud the hardest, you’ll win. But you have it, kid, and you’ll get there.”

What the director didn’t know was that no “street fight” could have discouraged Dewey Martin. That was pretty tame stuff by this time. As for Hollywood, the former farmboy who’d hitched his pony to a cart and hauled trash every Saturday for the treasured dime to go to the movies, found it a wonder that he was even there.

Dewey’s dad died during the depression “and things got so tough—my brother and I hired out to relatives to help them farm, until my mother could work and get us back together again.” He worked for his uncle in Oklahoma during the big drought. “There wasn’t any water. You drank water pumped from mud holes. It hit your stomach like lead.”

When his mother could reunite the family, they moved to Long Beach, California. Dewey worked from 4:00 P.M. until midnight doing scrub work around a restaurant and from 5:30 until 7:00 a.m. at a service station, while attending school. When war broke out, he was determined, education or no, to be a Navy combat pilot. This too, he achieved the hard way. He burnt the midnight oil studying, and he was one of 200 enlisted men in the whole fleet who passed the special required exam that admitted them to flight school. Of his inherent drive, he says, “I’m not too proud of it. I envy people without it. They live longer.”

But without it, Dewey Martin would never have made it in Hollywood.

It was during the war, when a USO unit of “Hamlet” came to Honolulu, that I “first got the idea of becoming an actor.” After the war, he worked up his own trucking operation, but his heart wasn’t in it. “It kept eating on my mind—that I wanted to act. If I didn’t try it, ’’d be wondering the rest of my life if I’d made a mistake.”

Trucker Martin got himself a theatrical magazine which listed all the summer stock companies, and one afternoon he sat down and wrote a letter to every one of them. “I got an answer from one in Maine, accepting me on the GI bill, as an apprentice. I rode a Greyhound bus for four days and four nights. I didn’t even know upstage from downstage.” Later, he moved to New York and continued his studies with a drama coach. But when some people driving to Beverly Hills offered him free transportation if he would help drive, he went along. He got a job ushering in a Hollywood theatre and finally, through a friend, got a reading at Paramount studio.

“I’d decided to make the big try. I had one good suit, a blue serge. Realizing I’d need an agent to represent me, I put on my blue serge one afternoon and walked in and out of every agent’s office.”

Dewey told them about his reading at Paramount, and one agent picked up the phone and called the talent department there. Then he hung up the receiver and said, “I think you’re wasting your time.” Dewey remembers how much that hurt.

Finally through another agent he got the reading that resulted in his part in “Knock on Any Door.” And Director Nick Ray encouraged him to stick around. Dewey thought jubilantly, “Now I’m set—I have some film.” Everybody he met had inquired whether he had “any film.” As Dewey says now, “I was so set I didn’t work for a year.”

He worked at a service station, as an usher at CBS, and finally wrapping packages for a department store. He was still wrapping them when he got a call out of the blue one day to read and be interviewed for a part in an important film.

“Again I thought this is it. And again it wasn’t,” Dewey grins now.

Months went by; then he tested for “Teresa.” Director Fred Zinnemann was enthusiastic but had to tell him reluctantly, “You aren’t right for the part.” However, Dewey’s test was carefully included among others being run for studio executives one night. For two years producer Howard Hawks had been searching for the right actor for a property he owned, “The Big Sky.” When they ran the rushes on Dewey’s scene, he turned to an assistant excitedly, “There he is—there’s Boone!”

“God bless that man,” Dewey says now.

To be Howard Hawks’ discovery, to have this coveted role, to be co-starred with Kirk Douglas—this must be it. . . .

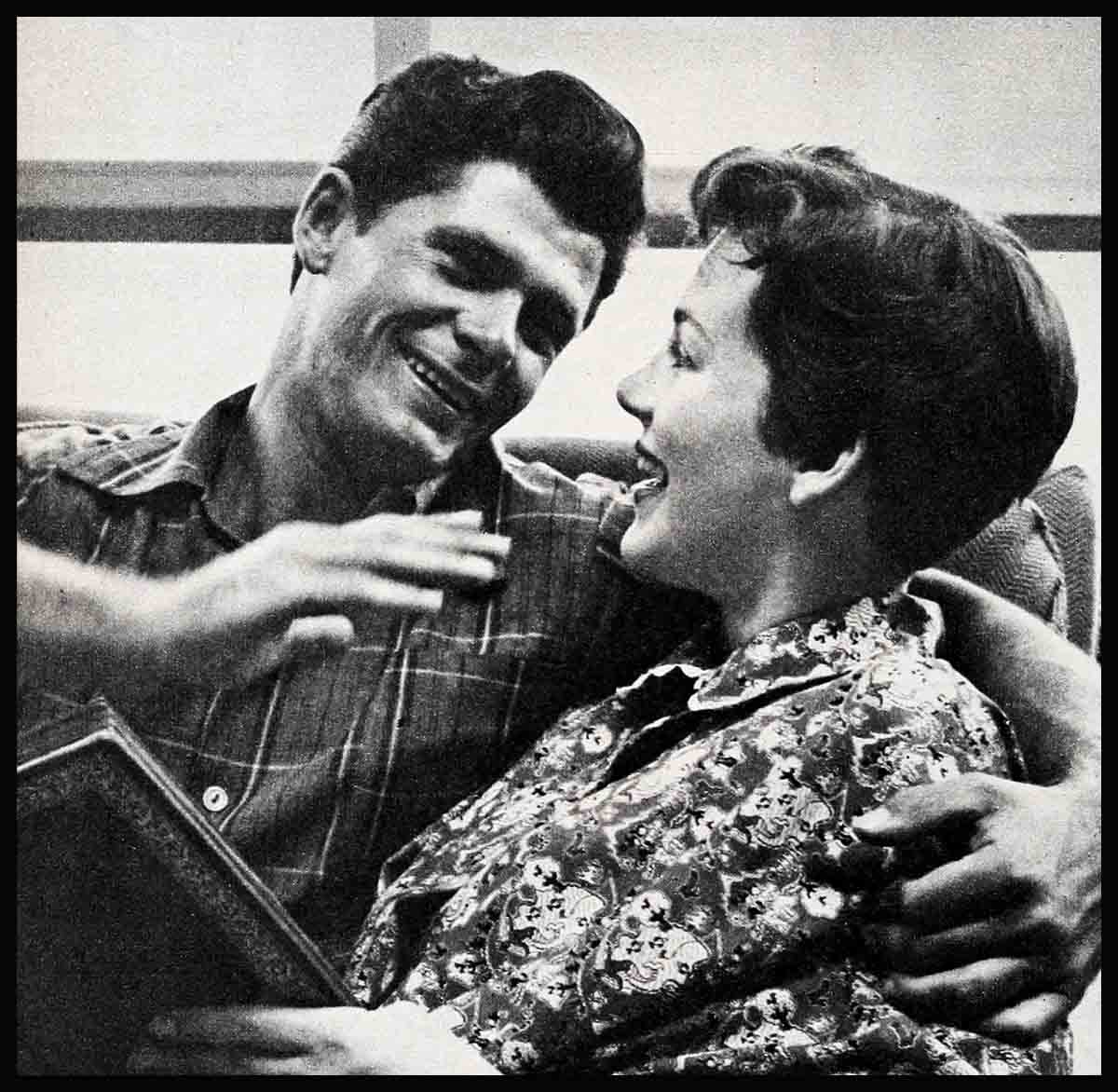

When he finished “Big Sky,” Dewey Martin went to Sun Valley to do a skiing layout for a magazine, and he was doubly sure. Mardie Havelhurst, twenty-two, a lovely co-ed from Oregon State, was working there doing publicity, and she posed with him for the layout. She was fresh and unaffected, with expressive green eyes, a lilting laugh, and the most intriguing red hair he’d ever seen. “I flipped when I saw her cute poodle cut,” says her husband, with a teasing glance in Mardie’s direction.

Back in her home town, Portland, Oregon, Mardie had always been very popular. An outdoor girl, she was her father’s favorite hunting and fishing companion. During the winter she attended Oregon State, majoring in music. Life was happy and full. Then one day while crossing the campus, chattering along with school friends, life seemingly stopped for her. It had been raining, and a prankish collegian, “a real ha-ha boy,” suddenly jumped on Mardie’s back to piggy-back across a mud puddle in front of them. “I went down. I don’t remember what happened, until I came to in the hospital.”

She had a crushed disc in her back. During anxious weeks that followed, specialists “didn’t think I would ever walk again.” They advised an operation immediately. “If you operate—what then?” Mardie asked, wanting and getting a straight answer. They couldn’t guarantee she would walk, but. . . “And if you don’t?” she asked. Then it would be up to God and time. “No operation,” decided Mardie firmly.

“I was on a board, laid up for months,” Mardie says now. “But she had the will to overcome it,” Dewey adds proudly. Finally she walked again, then as she gained strength, became almost her active self again. She took a job at Sun Valley, and met Dewey Martin.

They posed for pictures by the ski lift. They swam. They danced in the “Ram Room.” They went for a moonlight sleigh ride. And they fell in love. “Just all of a sudden, it happened,” as Dewey puts it.

“As corny as this may sound—it did just happen,” Mardie adds slowly. “It was as if we’d known each other years and years.”

“I’d been such a lone wolf. I had no desire to get married or to be a family man. If I hadn’t met Lucky, I still wouldn’t be married,” Dewey says.

They were married in the wedding chapel of the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas the day after the preview of “The Big Sky,” with Dewey’s future glowingly forecast. It was at the preview that Mardie realized she’d fallen in love with a motion picture star. “I’d never seen him on the screen. I just couldn’t realize the fellow up there was Dewey. It seemed so strange.”

During their first year together however, with Dewey’s mounting tension regarding his career, and with Mardie’s difficulty in adjusting to her new surroundings, their marriage began to show strain. Dewey began to wonder whether he would ever work again. As for Mardie, the whole motion-picture business was confusing. “Lucky likes a normal home life. She didn’t like living in a goldfish bowl.”

“We’d lived such different lives,” Mardie says now. “I’d always had my mother, my family and friends. Here I didn’t know anybody, and I had nothing in common with the few people I did meet.”

“Our family backgrounds were different too,” Dewey adds. “Mardie comes from a Norwegian family, and she was used to a close, warm family life, with all the holiday touches and the friendly get-togethers. She’s had to teach me to enjoy this. I’d always been afraid to like people.”

“We’ve both made adjustments,” Mardie says. “Dewey has so much drive; he gets so intense about things. I’m more lethargic. I’d just rather take things lah-de-dah. I’m sure this used to drive him crazy.”

But their confined living was the greatest source of unhappiness for her. “I felt so caged up in an apartment, and it was getting the better of me—”

This changed when they found the redwood-and-glass modern cottage at Malibu, with a horizon all their own, and the blue Pacific with its changing moods and music at their front door. And as option time neared again, Dewey worked off his restlessness answering fan mail, working with the lobster traps, and exploring the beach with their boxer, Calypso.

Then suddenly any anxiety about his career or options was relatively unimportant. For Mardie found she was going to have a baby. Along with their natural joy, Dewey was concerned for her. For the hazards, the discomfort, that motherhood might mean for her. He felt easier when Mardie went to Portland to consult the family physician who was familiar with all the facts of her nearly fatal accident. With Mardie’s aversion to goldfish bowls, Dewey was determined to keep this event, so sacred to them, out of the columns, if possible. And theirs was the best-kept secret in Hollywood.

With Fate’s dramatic timing, Dewey got his release, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer signed him to a long-term contract. They were starring him immediately in “The Tennessee Champ,” to be followed by “Panther Squadron Eight.”

“This is it, Lucky,” Dewey said, facing the cameras again.

But he’d never known more surely than that moment, that the kid from Katemcy who’d searched for security all his life, found it when he met his Lucky. And that gold halo he’d fancifully envisioned for movie stars belonged on Mardie’s own shining red hair. Success, as such, would be measured by their happiness together.

This, finally, was it.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1953