The Secret Clark Gable And Kay Never Shared

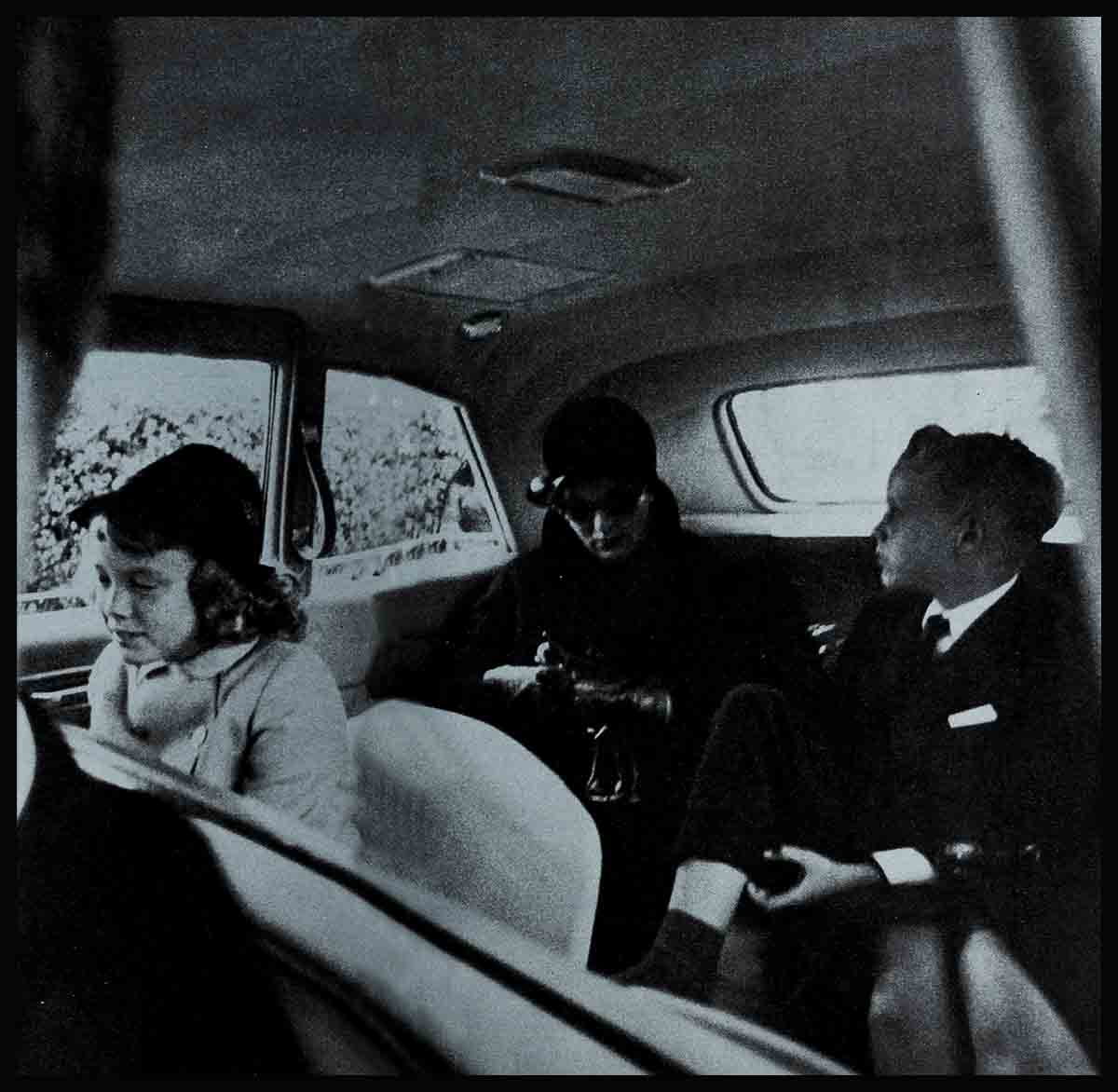

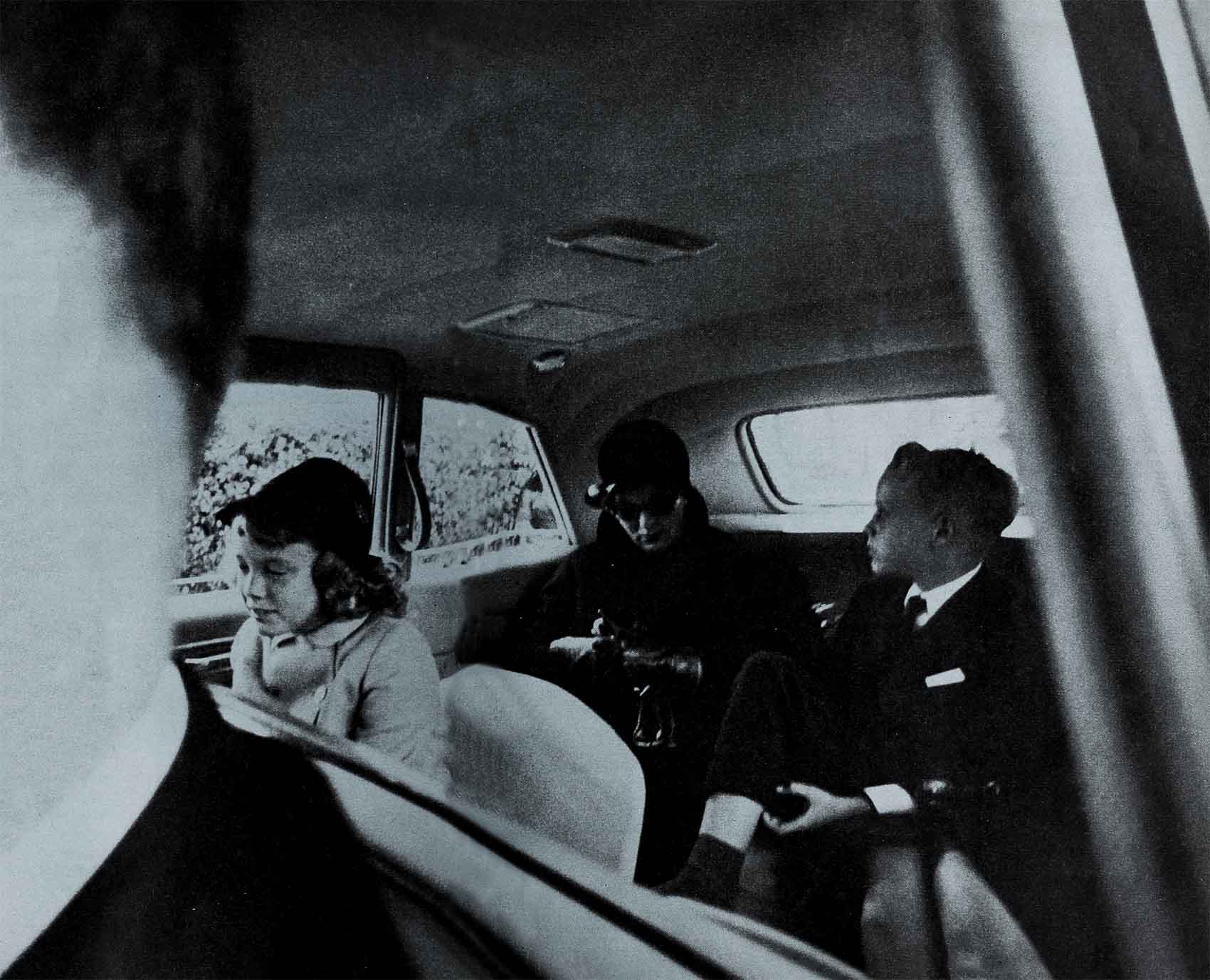

Kay Gable didn’t black limousine pulled away from the curb; she didn’t see her daughter, Joanie, lean forward and stare blindly into the onrushing cars; she wasn’t aware of her son, Bunker, turning stiffly to take a last look at the iron gates of Forest Lawn Cemetery. All she knew was that Clark was dead—and that soon he would be entombed in a crypt next to the one where his beloved wife, Carole Lombard, was buried. As they left the funeral, all she felt was emptiness as the limousine threaded its way slowly and carefully through the streets, heading towards Encino, heading for the house without Clark. . . .

She’d been married twice before when she first met Clark. She thought he was a surprising mixture of shyness and toughness, of self-consciousness and of concern for others, a man for whom words didn’t come easy.

She never mustered enough courage to ask him: What’s the matter? What’s bothering you? You just couldn’t do this with Clark. Some people said he’d built a high wall around his present feelings—and his past.

There was the theory—by people who didn’t know him, and by some who did—that he had never gotten over his love for his late wife, Carole Lombard.

There was hardly a person in Hollywood who didn’t have some story, some anecdote, some memory to relate about Clark and Carole. Their love, their marriage and their tragedy had become a real legend.

Their first meeting

Clark first met Carole in 1932 when she was his leading lady in “No Man of Her Own.” She was twenty-three, slender (her best friends called her “skinny”), frail, knock-kneed, with two small but noticeable scars on her face, the aftermath of a car accident. She’d had a nervous breakdown just before starting the picture with Clark, and somehow her pain seemed to bring a beauty to her, a quality to her magnificent flashing eyes and a sauciness and zesty irreverence that was irrepressible and irresistible. Whatever Clark felt, he never said, for at that time Carole was married to William Powell; and he was married to his second wife, wealthy Maria Langham.

It was not until three years later, when they met again at a dance, that they found things had changed. Carole was divorced, and Clark’s marriage had ended. A property settlement was all that was holding up his own divorce.

So they danced together—perfectly, as if they’d been in each other’s arms since time began. But some time during the evening she said something—or maybe he said something—and whammo! The sparks flew. Her ladylike voice let loose with some most unladylike words, and a minute later she flounced off the floor and out of the hall, leaving him alone in the middle of the room, red-faced from anger and embarrassment.

The next morning, at an unearthly early hour, there was a knock at Clark Gable’s door. There stood a messenger boy, and in his hands was a peace offering from Carole, a crate of doves. Months later there were doves all over—marking the many times they’d quarreled and the many times Carole had made up.

When he asked her to marry him—one month after his divorce became final—he said it was only because there wasn’t room in his place for any more doves. On March 29, 1939, he packed her into his white roadster and drove 750 miles to Kingman, Arizona, where they were married. She’d brought along a wedding cake in a perforated hatbox (“I don’t want it to get stale”), and when he opened it at their wedding supper, two doves flew out and fluttered around the room.

Because she loved him

They returned to Hollywood—he had to be back to make “Gone With the Wind”—and bought a 21-acre ranch in Encino. For months they didn’t go near a nightclub. Glamorous, sophisticated Carole got up before dawn to help feed the livestock; she learned to milk cows and pitch hay; she cooked lunch for her husband and brought it to him out in the fields where he was running the tractor; she found out how to hunt and shoot, how to tramp through the underbrush, how to spend the night on the side of a mountain in a sleeping bag. And glamorous, sophisticated Carole loved every minute of it because she loved Clark and he loved her.

One afternoon Carole left the ranch and drove to the set where Clark was making a new picture. His leading lady in the film had announced to everyone within earshot that she was going to add Clark to her collection. Clark and this actress were in the middle of a scene when Carole strode briskly out in front of the grinding cameras. Without breaking stride, she planted a swift kick on the actress’s back, midway between the shoulders and the knees. Then she announced to the director, “Either that (five-letter word) leaves the picture or Gable doesn’t work.” Hand-in-hand, she and her husband left the set.

Clark didn’t say a word until they got to the ranch. There Carole started sounding off again.

Suddenly, she felt powerful fingers lock tightly around both her wrists. She was jerked to her feet violently and found herself looking into Clark’s eyes, eyes that were as cold as ice.

“Listen, Ma,” he said in a voice as icy as his eyes, “if there’s any cussing to do in this family, I’m man enough to do it myself.”

She hid her face against his chest and began to weep. Gently he loosened his grip from her wrists, and stroked her blond, shining hair. “Everything all right now?” he asked. “But promise me . . .”

“Anything,” she whispered.

“Please . . . no doves!”

The day after Pearl Harbor, Carole and Clark offered their services in aiding the war effort to President Roosevelt. He replied that the best way they could serve was to do just what they were doing, entertaining.

Clark started making a new picture and Carole volunteered to help sell war bonds around the country. Just before she left to launch the drive in her home state, Indiana, they had a spat. The limousine came ahead of schedule to take her to the airport, so they didn’t have time to really make up.

“I wish you’d come too. Pappy,” she called over her shoulder.

“Otto’ll be with you—and your mother, so I won’t worry,” he shouted.

As the limousine pulled away, she made flapping signs through the window with her hands. First he thought she was imitating an airplane, and then he laughed as he realized she was pretending to be a dove.

Waiting at home

On January 16, 1942, he received a telegram telling him she was on her way home. At the end of the wire she added. “Hey, Pappy, you better join this man’s army.”

Carole was coming home! Clark arranged for a car and chauffeur from the studio to meet her at the airport. There’d be a mob scene if he went there in person.

He helped Martin, who’d been with him for years, set the table. He went out to the garden and cut flowers—roses from the bushes Carole had planted herself, and set the table with roses and tall candles and built a huge fire with fragrant pine cones in the fireplace. And he waited. . . .

But Carole did not come. The sound of a car door shutting, then Eddie Mannix, the producer and his personal friend, stood in the doorway instead. The color drained out of Clark’s face. He knew before Eddie uttered a word.

“Carole’s plane is down in the mountains. We’re going up there. You want to come?” Eddie asked.

They flew to Las Vegas and arrived in time to join a sheriff’s posse that was making plans to go up the mountain. As they entered the sheriff’s office, he was bent over a map, tracing out a route. “It’ll be easy to find,” he said. “You can see the flames . . . plane’s on fire.”

At that moment he looked up and saw Clark. “Got someone on that plane you’re interested in?” he asked.

“Yes,” Clark answered quietly, “my wife.”

He waited now, slumped down heavily next to his friend Spencer Tracy, who’d flown up to be with him.

When they brought the bodies down, Clark rushed forward like a madman towards the silent forms. Eddie Mannix, who had torn his feet ascending and descending the rocky, snow-covered slope, tried to stop him.

“No,” he said. “Don’t, Clark . . . for her sake, you mustn’t.”

But Clark pushed past him. “I have to see her. . . . I have to.”

He looked. For a long time. Then he buried his face in his hands. Yet he could not cry.

When Carole was buried five days later in a crypt at Forest Lawn Cemetery, he still could not cry.

He enlisted

He managed to finish “Somewhere I’ll Find You,” the picture he was making at Carole’s death. His co-star, Lana Turner, said, “I’ve never known anyone to suffer so much.” And the picture over, he heeded Carole’s last request and joined “this man’s army,” enlisting as a private. While flying bombing missions over Germany, he wore a chain around his neck. Attached to it was a small box in which were Carole’s jewelled ear-clips. They’d found them up on the mountain beside her body.

Kay never knew if this story had anything to do with what happened next, but one night, just about a year after they had started seeing each other, he asked Kay to drive him to the airport—he was going on location for “Homecoming.” She kissed him goodbye. He kissed her. Then the plane took off.

She did not hear from him—or see him again—for ten years. He just walked completely out of her life.

In 1953, he walked back into her life as abruptly as he had left. Both of them had changed. She’d been married to Adolph Spreckels II. the sugar heir, and had borne him two children, Bunker and Joanie. He’d been married to Lady Sylvia Ashley. Both their marriages had ended in divorce.

Not long after that in the garden at his ranch in Encino, amidst the roses Carole had planted, he asked her the question she’d waited ten years to hear.

“Kay’s made this such a happy home for me,” he said. It was just a few weeks before his death, and he was talking to a reporter. “She’s made such a happy life for me. Far more than I deserve. And now—this child. Her courage—with that heart she’s got—because she wants to do this for me. It’s far, far more than I deserve.”

Today, Clark Gable is buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery at his request, next to his late wife, Carole Lombard. His secret was a simple one—he loved two women deeply in his lifetime. Two different women. It took him ten years after he met Kay to accept the past, but when he came back, he knew he loved her—Kay was not another Carole. She was Kay Gable and he loved her—for herself.

THE END

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

Clark’s last picture is U-A’s “The Misfits.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1961

zoritoler imol

2 Ağustos 2023I have been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this site. Thank you, I?¦ll try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your web site?