Glenn Ford: “It’s Fun To Fight”

Some years ago, an ex-Marine and his pretty wife sat watching a championship fight on TV. It was a heart- breaking fight; because a long-beloved champ was taking a real beating. At any moment, he would be going down for the final count. As his public watched and mourned, in the lives of two of them, an important decision was being made.

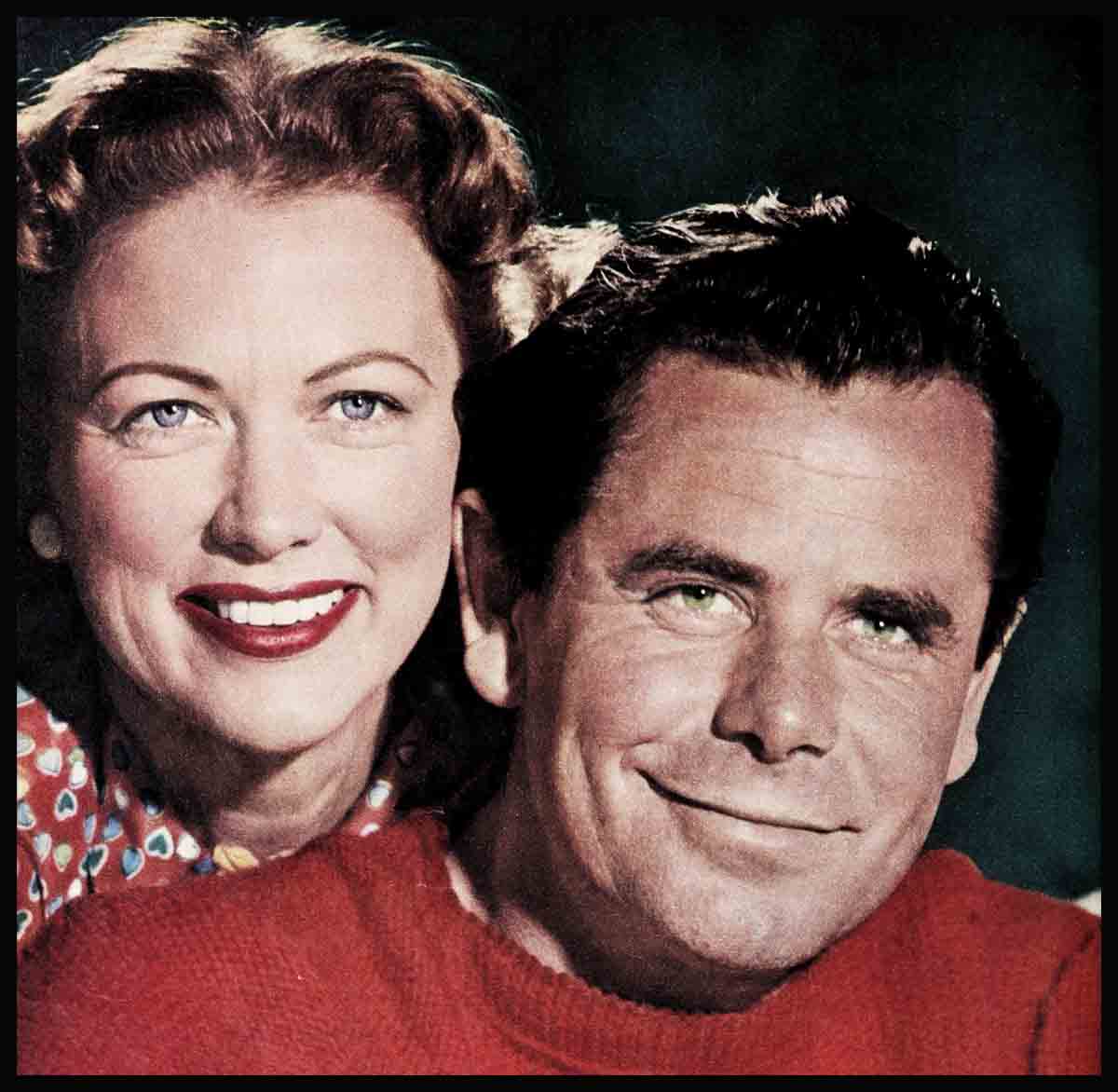

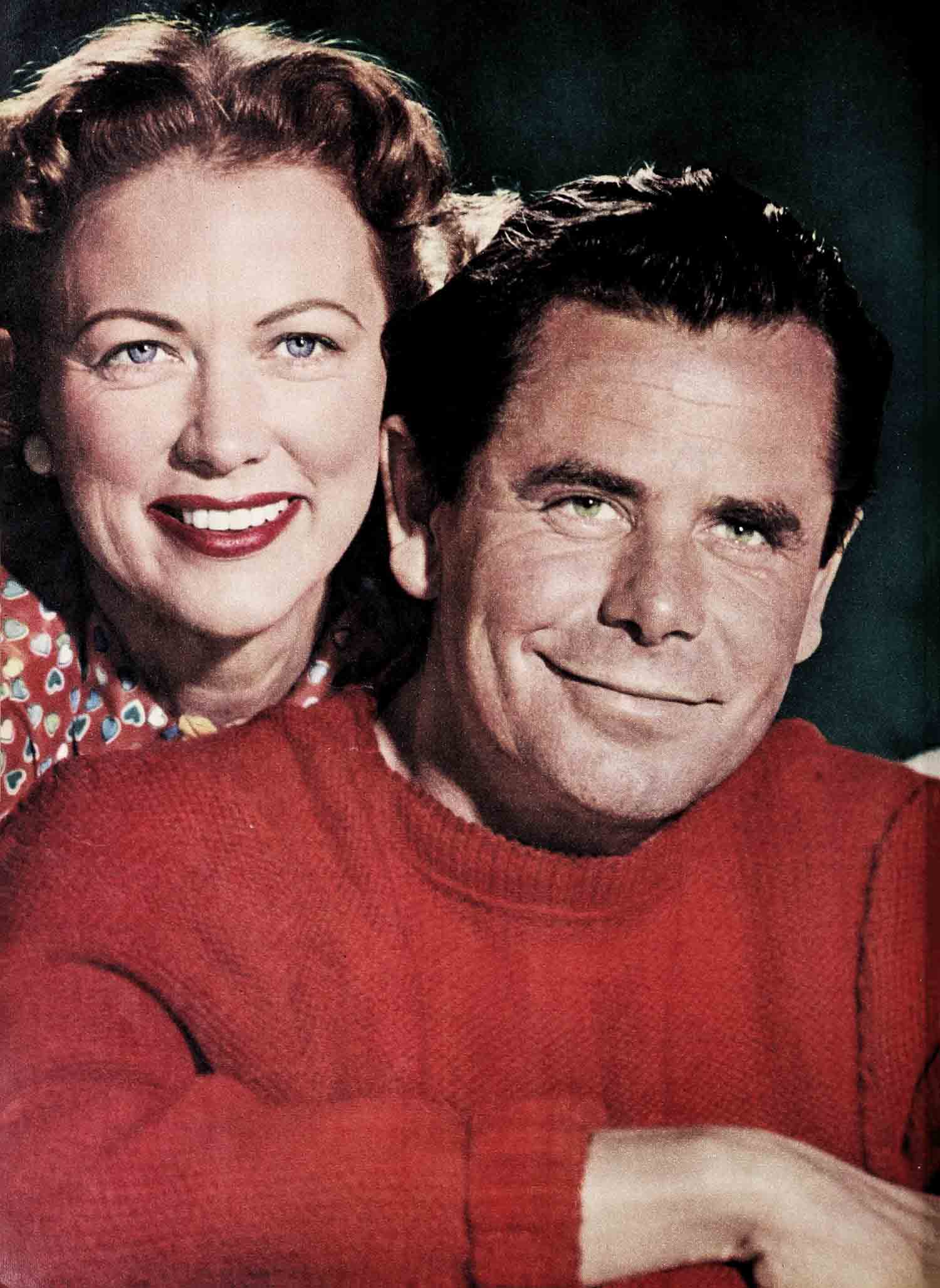

Turning to Glenn Ford, his wife said slowly, “He tried too long. This is what will happen when you try too long. I’m going to stop right now, while I’m on top.”

That night Eleanor Powell—whose twinkling feet had long made her the toast of Broadway, Hollywood and the whole world—hung up her magic dancing shoes. For, with the wisdom of one born to show business and with the instinctive faith of a woman fully in love, she knew that her husband would be champion enough for one family.

Glenn Ford had always had enough desire, enough ability, enough heart to make it. Nor was combat, in any form, a stranger to him. He had always had a natural inclination to stand up and be counted when the stakes were worthwhile.

Having heart had already brought Glenn reasonably far—otherwise, he wouldn’t have been able to withstand the continual shock and commiseration evoked by casting directors around town.: When he first set his sights on acting, he was a gangling, gawky youth with an off-beat face. He described himself as “the least likely to succeed” among the Santa Monica Players, where he had finally worked himself up from stagehand to stage performer. And he answered to such nicknames as “Slats” and “Hat-rack” (which Louis Calhern originally pinned on him).

“I never thought I’d make it,” Canadian-born Gwyllyn Ford says now. “The possibility of my being in movies was always the most remote thing. I didn’t dream I’d actually get there. It’s hard to explain, but there’s a sort of blind dedication that won’t let you quit. If you could see, the normal, sensible thing would be to stop. But you don’t. You plod and plod. You stagger, you rock, you get knocked down—and you pick yourself up and keep plodding along. There’s that stubborn dedication that, no matter what is said, no matter who laughs, you’ll keep on. Something inside keeps you going. So you work and struggle, and somehow you go forward. Then one day you’re driving along Sunset Boulevard and you ask yourself, ‘How in blazes did I ever get here?’ ”

How Glenn Ford got there, how today he is one of Hollywood’s hottest properties, is the story of an amazingly shy guy, with humility and sensitivity that is fortified by steel nerves and unwavering determination. It’s the story of a man of courage and rare compassion. Courage typified on the screen by starring in Hollywood’s most controversial films, such as “Blackboard Jungle,” “Ransom!” and “Trial”; the compassion to see, feel and fight injustice of any kind.

Experience and wisdom have combined to give Glenn an awareness that constantly reaches out to others. This awareness has been sharpened by his travels throughout the world, including the Iron Curtain countries, by his fighting for his country and himself. Thus he says today, “I’ve seen as much of life, probably, as much suffering, as any man my age. What one sees and is close to, one shares.”

Glenn’s story begins with his heritage. His parents, Newton and Hannah Ford, disregarded the plushy living afforded them by Mr. Ford’s social position and the family’s paper mills in Canada. They decided to start all over again in California, “because they’d read so much about California being the land of golden opportunity,’ and because they felt Glenn would have more advantages there.

Newton Ford—who died when Glenn was twenty—took a construction job. Glenn grew up sixteen miles from his future, with advantages even beyond those his parents had envisioned for him. At Santa Monica High, Glenn was a promising athlete, officer of his classes, and played the lead role in various class plays.

His intense awareness—which eventually became inherent in his acting—was early activated by battling the public for a living, and for the privilege of performing for them. Glenn sold weather-stripping, worked in a garage, managed a paint store, gardened and trimmed hedges, and learned a lot about life as a bus driver.

His bus-driving route took him along the beach between amusement piers at Venice and Ocean Park, and most of his patrons were in an amusement mood. As Glenn says, “I was the guy who worked while everybody else played. I worked during summer vacations, and on holidays. You had to learn to take care of yourself—there were always fights, with tough guys, drunks, or somebody trying to hop rides for free. I was forever stopping the bus and going back to straighten someone out.”

At night, Glenn worked with the Santa Monica Players. “I was stage manager, making the calls, running up and down stairs, yelling, ‘Places please!’ ”

Harold Clifton, who directed the Players and who today is dialogue director for Glenn’s pictures, recalls, “You couldn’t keep him away from the theatre. Glenn always had a great desire for the theatre. If he wasn’t in a show, he’d be backstage building sets, moving scenery, yelling calls—anything, just to be around it.

“I always thought he’d make it,” Clifton continues. “He had a basic talent and a warmth that projected. But the studios couldn’t see his screen possibilities at all. They were sure he couldn’t be photographed. We got good coverage from talent scouts at the plays. Impressed by Glenn’s performance, they’d set up interviews with talent heads to talk about a test. Then when we’d go to talk, they’d look at us like we were out of our heads. This happened all the time.”

Glenn’s rebuffs at every studio were legion. “Why waste my time, your time, and the boy’s time?” the talent heads would ask Clifton impatiently. “Tell him to go out and get a job. There’s no place in pictures for him. Even if he had the greatest talent, how could we photograph him?”

Glenn was too thin for his height. His voice was too old for his face. In fact not much of anything about him matched. “When Louis Calhern came to the theatre for ‘Golden Boy,’ ” Glenn grins now, “he tabbed me right. I looked like a hat-rack.”

But, for a sensitive young actor, he seemed remarkably thick-skinned. “Glenn wouldn’t say much about the discouragements,” Harold Clifton recalls. “He never seemed upset.” But the hurt was often there. As Glenn says now, “I’ve been helping with some casting lately, and I go out of my way to be kind to people. I remember only too well too many interviews when nobody even said ‘Hello-—when they didn’t even look at you.”

And those who did look didn’t buy. “I was a character-juvenile,” says Glenn, “and nothing is tougher to cast. I certainly wasn’t a Robert Taylor. And in those days if you were young and you weren’t good-looking, you weren’t considered picture material.”

Since the movies wouldn’t have him, Glenn concentrated on the stage. After appearing with Francis Lederer in “Golden Boy,” he got to Broadway briefly in “Soliloquy.”

“We went broke just before Christmas,” Glenn says. He remembers an ensuing scene which sounds as if it came right out of a melodrama. He was walking along Broadway on Christmas Eve. It was snowing, he was hungry, he had fifteen cents to his name, and he spent considerable time weighing the advisability of investing it in an apple machine.

Then one day, back on the West Coast, everything changed. Tom Moore, talent scout for 20th Century-Fox, had covered many of Glenn’s appearances with the Santa Monica Players and had always believed in him. Glenn was in San Francisco appearing with Irene Rich in “A Broom for the Bride,” when Moore called Director Harold Clifton to say, “There’s a picture we’re going to make. I don’t know whether they’ll go for Glenn, but Id like to try it.”

For a sensitive young actor—so dedicated, so eager to deliver, so grateful to be finally given the opportunity—Glenn’s first picture was a nightmare experience. The director, a former star, didn’t want Glenn in the picture, and put him, literally, through a baptism of fire.

“I’ll never forget his treatment,” Glenn says grimly now. “He did his worst to try to completely discourage me. This was his first picture as a director, and he must have resented bitterly the fact that the studio had given him a complete unknown instead of an established star. People told me he wanted me out of the picture. By belittling me and giving me a real bad time, he probably hoped to beat me down, break my spirit, to the point where I would quit.”

Ironically enough, when Glenn later hit the big time, the star-director boasted about having “discovered Glenn Ford.” But not for long. One night they met again at a dinner-dance. Ellie and Glenn were sitting with Tom Moore, the man who had given Glenn his first break, at the table next to the director’s and Glenn overheard him telling his companions how he had discovered Glenn. Glenn and Tom got up and walked over to the table. “I’d like to have you repeat that in front of me,” Glenn said, his voice ice-calm. And, as he adds now, “He didn’t—and he never has since.”

That experience—plus a few others—further inspired Glenn to keep a vigilant eye out for any injustices to newcomers through the years. “I never want to see done to them what was done to me, and I’m not going to,” he says.

But there were also some unexpected assists, in the beginning. Hollywood first took note of newcomer Ford when Columbia Studios, to whom he was under contract, loaned him out for “So Ends Our Night,” starring Margaret Sullavan and Fredric March. As a friend who was with him in that picture recalls, “Both Fred and Maggie gave Glenn every advantage while we were making the picture. They liked him and they went out of their way to help him. The picture was sneak-previewed in Santa Ana, and Glenn. was pretty awed, seeing himself in an important role for the first time. But he didn’t realize what had happened. Maggie and Fred, however, realized very well. The picture was Glenn’s.”

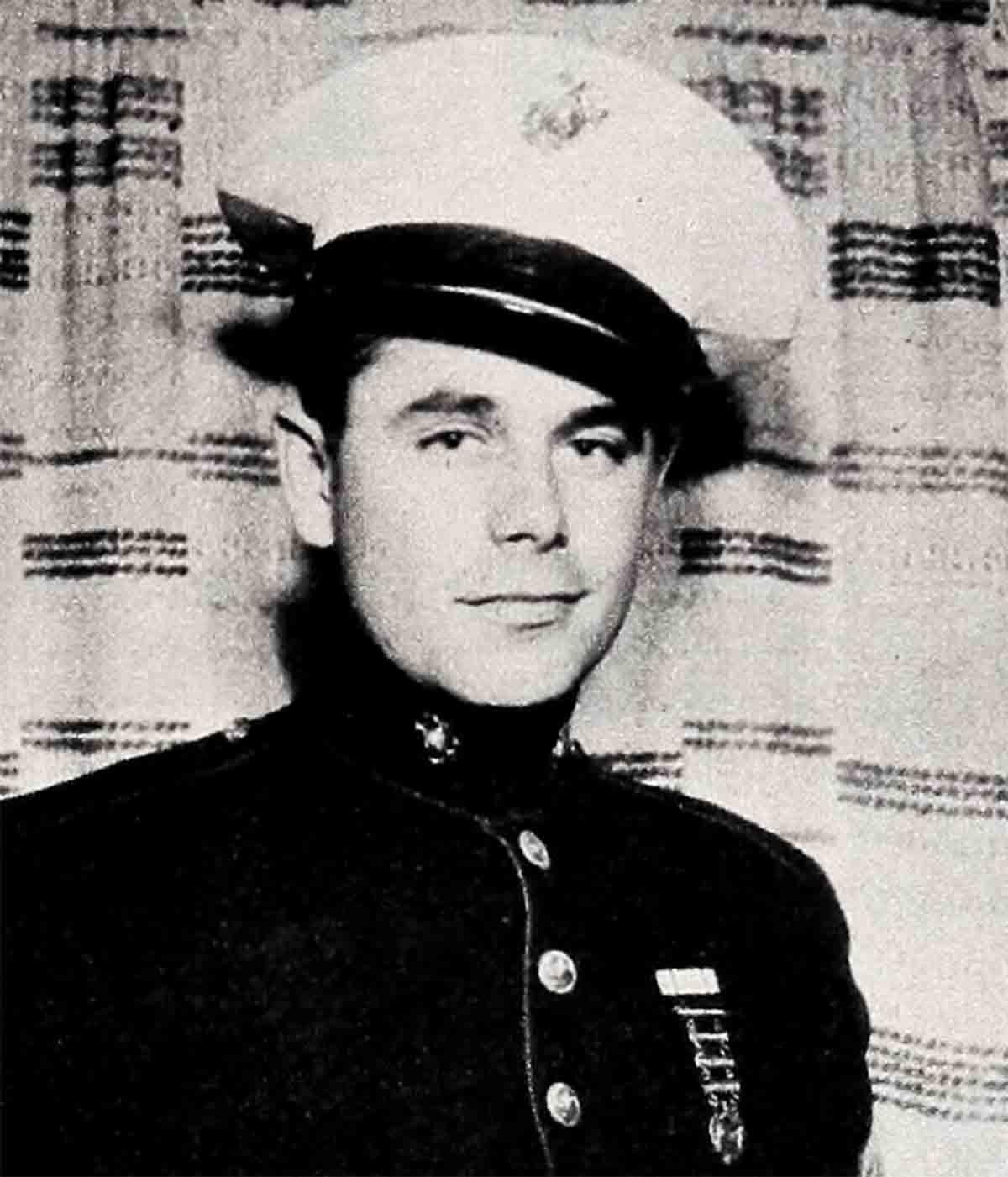

Characteristic of Glenn, when Columbia assigned him the lead in “Song to Remember”—the part which would have made him an important star—he turned it down to join the Marines. He was all set for the picture, and Paul Muni was coming to Hollywood to make it with him. By doing it, Glenn would have been deferred from service for several months of very rough fighting. And he would have realized, at long last, the big dream of being a motion-picture star. But two weeks before the picture was to roll, the draft laws were being revised. “You couldn’t enlist in the branch of service you wanted,” Glenn explains, “and I wanted to be in the Marine Corps.”

With a war still standing between him and stardom, Glenn fell in love with and married Eleanor Powell, who was then at the peak of her career, but was willing—even wanted—to give it up for him.

Contrary to the opinion of many, Glenn never wanted Ellie to give up her career. “Oh, no,” he says emphatically, “I was the one who objected when she talked about giving it up. As it turned out later, it was all right. I realized this was what she wanted and that she was happy about it. But I felt terrible about it at the time, and nobody was happier than I when she had to go back into it in a different field.”

Glenn’s concern had nothing to do with their respective careers. “I never even thought about that when we married,” he says. “I wasn’t thinking beyond the war.” At that time, the fighting in the Pacific was going badly. Casualties were high. and no realistic Marine was making any postwar plans. “I never figured I’d get through it,” Glenn says now. “I don’t think anybody in our outfit did—really. When Ellie kept talking about giving up her career, I was worried. If anything should happen to me, I thought, what will she have then?”

From the beginning, it was Ellie’s own idea. “I realized,” she explains now, “that, to make a success of marriage, the man has to be the head of the house, to be looked up to. This isn’t only true of Hollywood, but anywhere. And any woman who thinks differently is, I believe, making a sad mistake.”

Furthermore, Eleanor Powell welcomed the personal challenge of being a wife and homemaker—of proving to herself that dancing was not her only accomplishment. That she was the top dancing star, Ellie felt, entitled her to no particular credit. She’d been dancing all her life.

The fourteen weeks they had together before Glenn was shipped overseas-—when Ellie managed their small apartment in La Jolla and carted her way around the local grocery store—were “the happiest of my life.” When their son Pete was born, two years later, she felt her fullfillment as a woman was complete. And one night, via TV, as she watched a champion going down, Ellie decided definitely to retire while she was at the top.

As for Glenn, Ellie’s faith in him and in their future together was a boost when he needed it most. Particularly during his last weeks in the Marines, when he kept reading all the condolences in the papers and magazines for the boys who’d gone away, and the speculations about the bright futures of those who’d taken their places.

“I was pretty discouraged,” he recalls. “People kept telling me how Hollywood had ‘progressed so much’ while I’d been away. I came back not figuring on too much. I knew I was fortunate just to be back. Still, it was pretty dismal thinking.”

But fate crossed Glenn’s path immediately with a star of kindred will. He was having lunch with his agent in the Green Room at Warner Brothers one day when Bette Davis was lunching there.

“Who’s that young man sitting on the other side of the room?” she asked the writer with her. “I don’t know who he is, but I’ve seen him.”

She was told he was Glenn Ford. “Oh, no, that couldn’t be Glenn Ford,” said Bette. “He’s in uniform and out of the country.”

“Well,” said the writer, “that’s Glenn Ford back home—and in a tweed suit.”

“Ask him if he’d like to make a test with me,” Bette Davis said.

When she saw the test, Bette went straight to the front office. “I want Glenn Ford for my leading man in ‘A Stolen Life,’ ” she said. They said no. “We’re pushing another boy who’s under contract here. We want him for that part.” Furthermore, they said, Glenn Ford was under contract to Columbia. Also, the picture was set and they were going to start shooting on location at San Clemente, California, the following week.

“Well, boys,” said Bette, “I’m going to Laguna. When Glenn Ford shows up in San Clemente, give me a buzz. But don’t call me until then.”

Following “A Stolen Life,” Glenn was given the lead in “Gilda” with Rita Hayworth. His star had started to zoom. And one sunny day, as Glenn puts it, “I was driving along Sunset Boulevard in my first convertible, feeling pretty proud,” when he heard a familiar voice. “Hi, Hatrack! I see you made it,” yelled Louis Calhern.

But Glenn Ford had only just begun to move. Characteristically—even after his long struggle to get inside those studio gates—when he felt his studio was giving him mediocre roles, Glenn refused to sign another contract. This was at the risk of an indefinite suspension he could not afford to take then. But no amount of badgering or pressuring would budge him. “No, I’m sorry,” he told them. “Maybe you’re right, but I can’t do it.”

Glenn was holding out for a non-exclusive contract that would provide for him to do one picture a year for his studio as well as give him all the loanouts and fees from all outside appearances, such as radio shows. And he won.

Typically, Glenn took his new “citizenship” very seriously. He never hesitated to voice his convictions in any sphere, He served for six years on the board of directors of the Screen Actors’ Guild. Out of his tremendous respect for his profession, he has never hesitated to fight injustice on the part of any of its membership.

Success only increased Glenn’s vigilance in keeping an eye out for the underdog, and the stories about him are legion.

One director was given a $25,000 lesson in good manners when he berated an elderly little woman extra on the set of one of Glenn’s pictures. “You stupid’ so-and-so! Didn’t you hear my instructions? What’s the matter with you?” the director was thundering because the extra was a little late with a bit he’d given her to do in a scene. He looked up, frankly startled, when Glenn walked over, saying, “I want you to apologize to this lady, or the company shuts down—now.”

It was two o’clock in the afternoon. They were shooting on a huge, lavish ballroom set, using 750 extras, and time was indeed money. When the director made no move, Glenn apologized to the extra for him and walked off the set. “I’ll be at my home,” he said. “When you apologize, let me know.”

All action stopped. Various studio committees deliberated with Glenn, but to no avail. At five o’clock that afternoon, the director finally apologized.

Glenn admits he has a temper, “and when I blow, I go good.” But when he “blows,” it’s usually on behalf of those who can’t afford to fight for themselves.

Glenn’s vigilance in this respect sometimes has his devoted stand-in, Bill Reinhart, worried—not for himself but for Glenn. “I’d rather have him in my corner than anybody,” says Bill. “When it’s tough, I’ll take Glenn. But sometimes it worries me.”

Stand-ins are paid by the day and only when they’re called. Glenn has educated studios never to call him without calling his stand-in.

One afternoon, a studio called Glenn to come in around four for a “quick pick-up shot” for a picture he had made.

Upon arriving on the set and not finding his stand-in there, Glenn asked, “Where’s Bill?”

“We don’t need him, Glenn,” the production manager breezed. “There’s not much to it. You just walk through—”

But Glenn insisted. “You know the understanding,” he said. “When I’m working I want my stand-in here.”

“I was in the bathtub when the phone rang,” Bill recalls now. But Glenn told him he didn’t have to break his neck rushing to the studio. “We’ll wait. Take your time.”

“It was a few minutes to six by the time I got dressed and out there. And when I walked in, the whole company was sitting around waiting for me,” marvels Bill.

As soon as Glenn saw Bill come in, he said, “All right, we can make it now,” and walked right through the scene. But Bill got a check anyway. “For $17.85, Glenn shut the whole company down for me.”

Consequently, Bill Reinhart who’s been Glenn’s devoted stand-in for the past seven years—worries about the way Glenn sticks his neck out for him, and tries in his own way to protect Glenn.

“Glenn barges right in where angels fear to tread,” says Bill. “The way he’ll stand up to people for you—it’s really something. What frightens me is, he’ll never back down. Glenn’s ’way up there now, he’s a big star. And for a fellow of his standing, you’d think he’d have a little more caution. Nowadays, if anything comes up, I look around and make sure Glenn’s far away before I say anything.” Which isn’t easy to arrange. “He watches me like a hawk,” says Bill.

Similarly, nobody will fight harder for the motion-picture industry as a whole and the many fine hardworking people in it than Glenn Ford. He burns when Hollywood is attacked and distorted pictures are painted, or when the majority of its citizens are made to suffer for the behavior of a few. He has no truck with those who “won’t pass up the chance to make a buck at the expense of so many.”

By nature, Glenn is terribly shy and soft-spoken—unless there’s a need to be heard. Perhaps his biggest challenge in life is the continuous inner struggle between his own two conflicting desires: His determination to avoid the spotlight personally, and his dedication to a profession which thrives on it. He admits to “a continuous desire for anonymity, which isn’t always possible in my trade.”

But, for a star of Glenn’s stature, he manages this remarkably well. He avoids night clubs, premieres and plushy parties. “If I thought it necessary to live like a star—to be seen in the right places by the right people and so forth—it would be pretty tortuous,” he says. “But I don’t hold to that. You can live a normal life in our business. That’s up to the person, not the profession.” However, Glenn does have one long-standing social date: The regular Wednesday-night poker game with the same seven guys, which includes Charles Ruggles and Edgar Buchanan. Glenn says the losses are never too large. “It evens up—in fourteen years.”

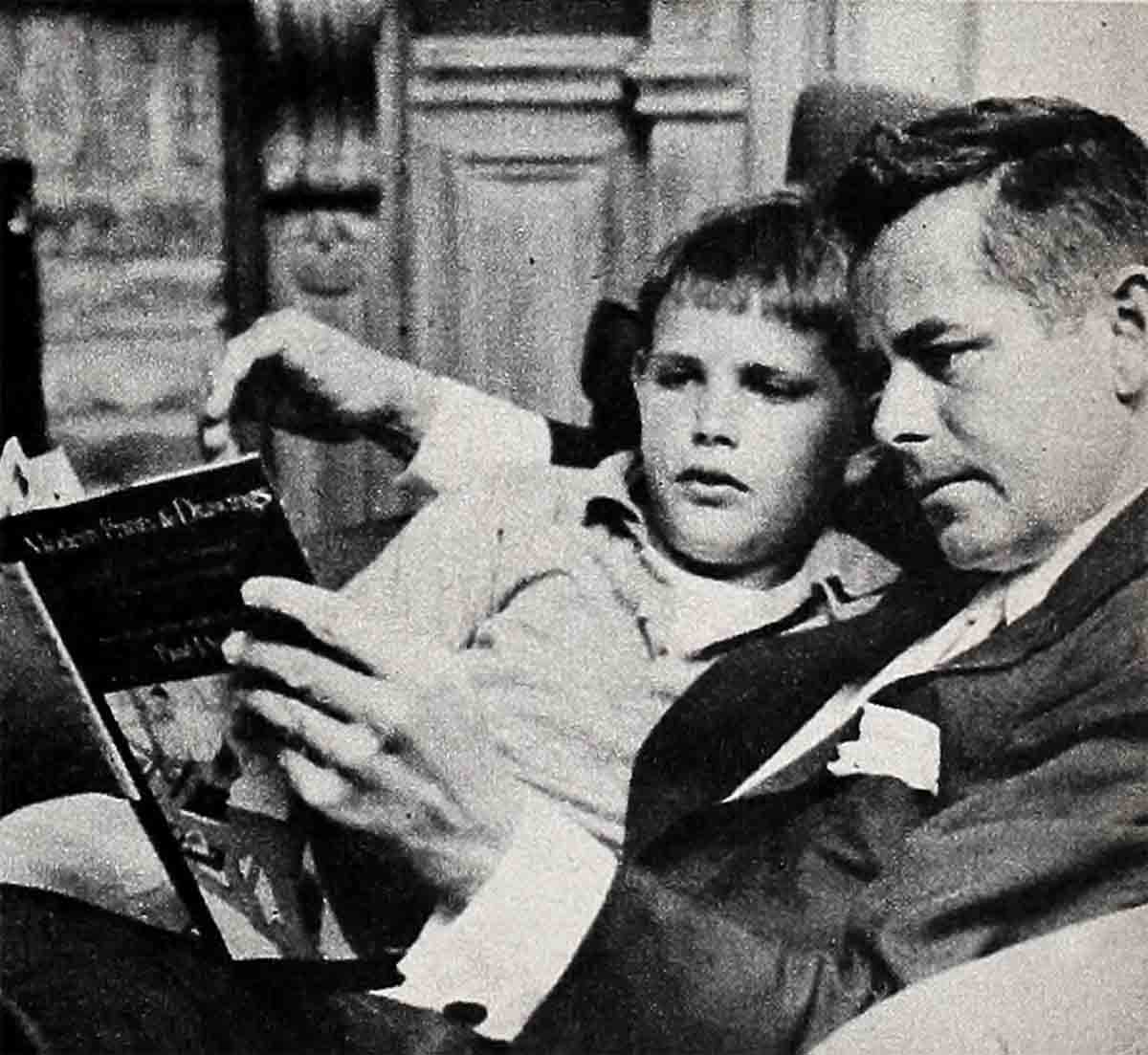

While he is so intense and preoccupied when he’s working that he could pass by his best friend without knowing it, between pictures—at home with Ellie and their eleven-year-old son Pete—Glenn’s as relaxed as a hibernating bear. When pressured, he admits that for a man of such reputed strong will he’s a pushover for son Pete. “I don’t like to be told this—but it’s true,” he grins.

Ellie says her husband and son are like two cub scouts bucking for corporal when Glenn’s home. “For some time now they’ve been engaged in a building project that’s going to be a clubhouse or a fort or some- thing. They’re out there working on it like twin beavers every available moment they have. The way they’re going about it—pounding and pounding, sawing and sawing,” she laughs, “you’d think they were preparing a summer cabin for President Eisenhower! It keeps getting bigger and bigger by the moment. I think they’re getting ready to take in boarders out there.”

Glenn and Ellie are determined to see that Pete’s life won’t be warped in any way by being their son. And there seems to be small worry on this score. For example, last year, after talking it over, Glenn and Ellie decided to let Pete stay up past his bedtime to watch the Emmy television awards. Ellie didn’t think she’d win anything, but “I thought if I should happen to, it might be the only time in Pete’s life.” When they got home that night there was a note from Pete. “I’m so happy you won the Emmy,” he’d written. “But I was a little ashamed of you, Mom. You ran so fast (to get it) you looked greedy.”

“Pete and Glenn and I are all note-happy,” says Ellie. “We’ve been sending notes back and forth to each other for years. If I have to go out and speak at different churches, during a period when Glenn’s working on a picture, he’s in bed when I get home. But I’ll find notes from him in little out of the way places around the room. He’ll be mad at me for telling you this—”

When Glenn’s engrossed in a part, time is relative and the rest of the world goes by. He may forget to send red roses on Valentine’s Day, but as Ellie says, “He’s very thoughtful in his own special way. One day when I came home, there was a little porcelain angel on my bureau.” This was Glenn’s way of saying, “You’re an angel.” And, as Ellie adds, “I’d rather have a sentimental note or gift like that than an expensive gift on an established day.”

This is the Glenn with the wide streak of tenderness—as Ellie and Pete well know—who writes love notes and hangs on to sentimental souvenirs, such as his “lucky tie.” This is a brown knit tie he bought for a dollar when he was in high school, wore in all the class plays, the little-theatre plays, “in my first picture—and I’ve worn it ever since. I’ll bet it’s cost

Metro $500 tc have stand-bys made to match that dollar tie,” he grins. And this is the Glenn whose proudest possession is an 18th Century music box that “rocked my grandfather to sleep, his father, my father, me—and Pete.”

When Pete was younger, Glenn’s extended movie-location trips often kept them apart, but now Glenn is determined not to be separated from his family. In April, he is going to Japan to make “Teahouse of the August Moon.” But, as Glenn points out, “This is the first faraway location since I went to South America four years ago, and then I took Ellie and Pete with me. ‘Teahouse’ will be made while Pete’s in school, and I’ll be back to spend the summer with him. And, if Ellie can get time off from her TV show, she and Pete will fly over while I’m there.”

Although he teases Ellie—saying, “I thought I was marrying a dancer; I didn’t know I was marrying a missionary”—no husband could be prouder than Glenn is of Ellie’s Sunday-school TV show, Faith Of Our Children. He also helps with the scripts and lends a hand whenever he can. And he admits it’s perfect casting. “She’s the darndest missionary,” he laughs, then adds seriously, “Nobody could be more qualified to teach Sunday school than Ellie. She’s so beautiful and sweet and patient and good. Ellie sees only the good- ness in this life.”

Eleanor Powell’s experienced understanding of show business and of Glenn’s intense dedication to his work has played an invaluable part in their marital happiness. Glenn is one star who admits he takes his roles home with him. “Ellie always grabs the scripts first when the studio sends them over. She wants to see what kind of man she’s going to be living with for the next three months.

“I don’t know any serious actor who shrugs off his role when he goes home at night,” Glenn continues. “And don’t tell me you can be a teacher in a tweed suit in ‘Blackboard Jungle’ all day on the set from nine until six, go home, get into a tux, drink champagne and go night-clubbing, and the next morning be the teacher in the tweed suit again. I don’t think good results can be achieved that way.” Instead, Glenn lives with his character throughout the picture, spending hours with his tape-recorder in the evenings, going over his lines.

“Ellie would be so happy with the genial guy I play in “Teahouse of the August Moon,’ but,” he grins, “we’re making that one in Japan.” However, his next picture—“The Fastest Gun Alive,” a psychological Western—has been going over very big on the home front. “Westerns are a big favorite around our house,” says Glenn. “T’ve been practicing to draw fast—which makes Pete the happiest fellow in the world. I’m really the favorite father now.”

After extensive research, Glenn even mastered a fancy gun twirl—“to impress my son”—then he had to talk hard to keep he studio from incorporating it in the picture. Finally confronting them with a load of research material, he convinced them that real gunmen had no gimmicks—they only took time to draw.

Although “Blackboard Jungle” and “Trial” were not favorite “home movies,” Ellie is proud of Glenn’s performances in them. That Glenn has the courage to star in such controversial themes, surprises nobody who knows him. For this is the story of his life.

“I was told I shouldn’t do ‘Interrupted Melody,’ that the part was secondary to the woman’s,” says Glenn. “But I feel a good part—if done right—stands a chance of being important. I made ‘Blackboard Jungle’ against the advice of others. From that picture snowballed everything else—‘Ransom!’, ‘Teahouse of the August Moon,’ signing my M-G-M contract—”

Answering to his own mind and heart has been a life-long habit of Glenn’s. He had his own reasons for wanting to make “Blackboard Jungle” and “Trial.” He knew them by heart, and by memory. Grim memories.

“I’ve traveled around the world a lot,” he says, “and I’ve traveled in the Iron Curtain countries. I’ve heard us criticized for being ‘infantile,’ for making ‘sugarcoated fairy tales.’ I’ve heard us sneered at and laughed at. Mostly they call us ‘children’—which I resent. But with the pictures I’d made up until then, I had no answer for them. Mine had always skirted life, taken the easy way out. If I’d already made a ‘Blackboard Jungle,’ I could have shut those people up. A picture like this proves they’re not telling the truth about Americans not being able to face our own social problems.”

Throughout the filming of this one, phrases had kept coming back to Glenn. Taunting phrases and faces he’d met. During an interview in Austria, a Communist reporter had asked, “Tell me, Mr. Ford, is Hollywood still making fairy tales for children?”

And a French reporter had queried, “What are you Americans trying to cover up? ”

“What do you mean?” asked Glenn.

“Everything can’t be a Technicolored dream in America. What are you trying to hide?”

“Nothing,” said Glenn and felt like shouting it. But he had no pictures for proof.

When the cameras stopped turning on Glenn’s gripping staircase scene with the young Negro actor in “Blackboard Jungle,” he thought, “How I’d love to be sitting in the theatre in Vienna when that scene goes on.”

Glenn has found the controversial opinion about making pictures like this encouraging. “It means people are thinking,” he says. “If a picture makes people think, then we’ve done good. No matter whether they are free or not. The important thing is to think. This is what made America. And as long as people think, we’re in great shape.

“Like my son,” adds Glenn. “If Pete differs with me and says why, that’s stimulating, that’s good.” Honesty, however, compels Glenn to admit that it can also be uncomfortable. He has never wanted Pete to be impressed with the fact that he is the son of a movie star, but one night recently he decided to make an exception and take him to one of his pictures.

“Pete, they’re sneak-previewing my picture in Westwood tonight,” he announced. “Would you like to go with me?”

Pete thought for a minute. “Well, gee, thanks Dad,” he said finally, “I don’t want to hurt your feelings or anything. But— well, tonight Rin-Tin-Tin’s on TV.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956

No Comments