“Was I A Fool To Love You, Elvis Presley?”

Elvis darling,

I couldn’t sleep last night.

I kept thinking of another night—just before you left with your unit for Germany. Remember how you held me in your arms and kissed me? Remember how you said, “I love you, Kitty. You’re one girl in a million—you’re the most sincere. I know you never wanted anything from me.”

You were right in away. I never wanted anything like gifts. No diamonds. No furs. No glitter or glamour. Nothing that money could buy. I didn’t even want a wedding ring, unless the day came when you would proudly want me to wear one.

There were times, during those magic days and nights we spent together, when I hoped that some day we could belong to each other forever.

We’d shared so many things—the rapturous moments, and the saltiness of tears, and many moments of laughter. “You’re my girl,” you’d say to me wistfully. “Will you still be my girl while I’m away?”

And I’d answered, “Of course, Elvis. I’ve never known anyone like you.” And you said, “And I’ve never known anyone like you, baby.”

Now you’re more than 3,000 miles away. Or is it 6,000? I was never very good at figures. But when I saw the stories about you and the beautiful German girls—frauleins they called them—who had fallen for you, I trembled with fear. So many American soldier boys, I know, had married foreign girls while they were overseas. And later when they were asked what those foreign girls had that the American girls didn’t, they said frankly, “Nothing, but they were close at hand. . . .”

Elvis, I’m scared. I’m afraid, like the day I picked up a paper and saw a picture of you and one of those frauleins—especially that picture of you kissing one named Margit, your face lighting up with that boyish grin. That made my heart turn somersaults. The mere thought of you still makes my heart pound fast. When a girl falls in love with a boy like you, Elvis, the feeling is suffocating. But for you, my darling, caught up in a new world, will the memory of our kisses and our unfinished love story be enough . . . ?

I never realized how susceptible I could be till the day I met you, darling. I’d met so many boys; so many have asked me for dates; so many have told me that I was pretty. And of course, I’d gone out with many boys before I met you. But there was something we captured together that I’ve never known before or since. Were those stars we saw? Was it the thunder of love that roared in my ears? Why did the moon seem closer to earth when you were with me? Why did I feel such a pang of anguish whenever you suffered for even a moment, darling?

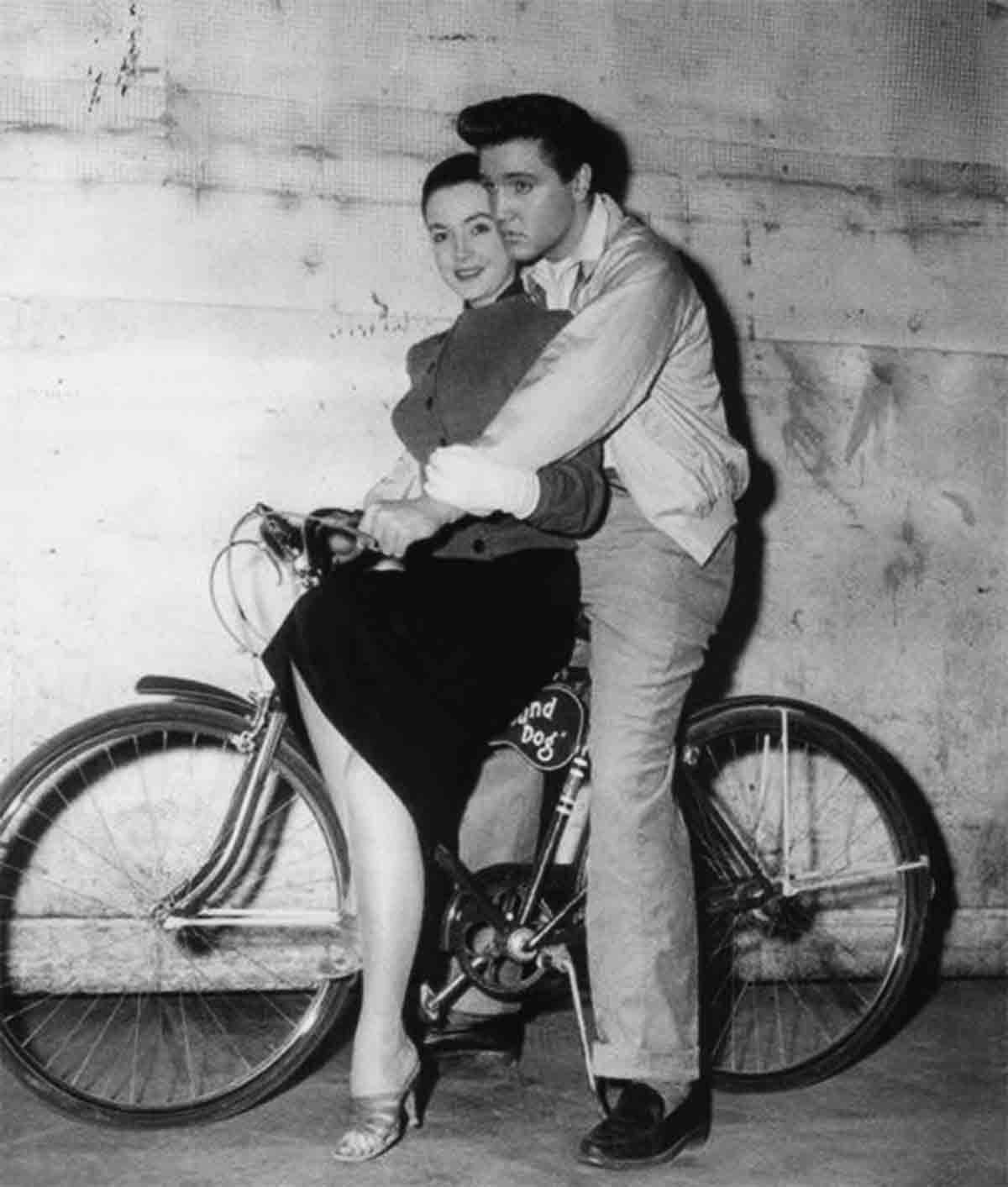

Our romance began in such a gay, happy fashion. Remember that evening in Las Vegas last September? I’ll never forget it. I was singing in the chorus of the Tropicana then—just one of many girls in the line.

And on that evening when I was to meet you I was with a boy friend in the lounge. Then you walked in, and an electric current went through my back.

It takes a lot to attract attention in Las Vegas. The town’s so used to the most fabulous people in the world. But there you were, in a maroon suit, flanked by five boys in black suits, and everyone’s eyes suddenly turned away from the gambling machines, the gaming tables, the girls in their bright evening gowns, and fastened on you. Everyone looked at you.

All the eighteen girls in our show had gathered around you. They had all made a dash to your side and were fussing over you.

You winked back!

I wanted so much to be one of them. I’d admired you ever since I was a senior at Marymount Academy near my home in Pearl River, New York . . . when I thought you sang with feeling and soul.

Although I wanted to attract your attention, I was too proud to rush into that mob of girls and compete with them for one look from you. So first I put on my special aloof look. It was such a contrast to the gushiness of the other girls swarming around you, that your face lit up and you looked right into my eyes. Then I turned around and slowly winked at you. And you winked back!

A moment later, one of your five boys came over to me and grabbed me by the arm. “Elvis wants to meet you,” he said.

I was thrilled, but I didn’t want to show it, so I answered coolly: “Give him this message: Speak for yourself, John Alden.”

Out of the corner I watched him run back and give you my message. I saw you laugh. Then you got up and sauntered up to me.

“I hear your name is Kitty,” you said in that husky voice of yours with the Southern drawl. “That’s a pretty name. And you’re a beautiful girl. I noticed you on the stage. I told myself, ‘I’ve got to meet that black-haired, green-eyed doll.’ And here we are. I’d like to see you, Kitty. Can we make it tomorrow?”

I’d always believed that a girl mustn’t be too easy to date if she wants to attract someone special. But I couldn’t say “No.” I compromised. “Tomorrow afternoon,” I said.

The next afternoon I was ready for you. I’d spent an hour doing my hair, making up my eyes so that they’d look even greener, and putting on black slacks and a white sweater that showed off my figure. I heard a loud whizzing sound outside my apartment, and there you were on a motorbike, so handsome in a white suit and a white leather jacket that I just about flipped. You told me later that you flipped, too, when you saw me.

Remember how we rode up and down the Strip in Vegas, and through the side roads, howling with laughter and singing? You were like a boisterous child, and my heart sang with you.

We pulled up to the Sahara Hotel, and you rode your motorbike right onto the grass beside the pool, making everyone jump and stare. You wanted to show everyone in Vegas your motorbike, and you did. All the time you were singing—songs like Autumn Leaves and I Believe. I didn’t know why you were singing about autumn leaves, but I knew why you were singing that wonderful song, I Believe. It was the expression of your faith in God and the universe. I felt a catch at my throat as you sang.

What wonderful days and nights followed for us! We saw all the shows, staying up all night to go from one place to another. For the ten days you were in Vegas we were together constantly.

You didn’t care to dance, so when we went night-clubbing you’d sit through the shows, applaud the other performers and tell me how lucky you felt to have so many fans when there was such great talent everywhere.

You were so tender

I felt so close to you, darling—getting to know you better than any other girl had, you’d say. We’d have breakfast, lunch and dinner together. Remember how I kidded you because you’d have the same meal three times a day—bacon sandwiches and Cokes. Mostly, we ate in your apartment. Even when we had a little party, we’d have no hard liquor, only Cokes. You were so very tender with me, darling, so different from any other boy I’d known. You were always polite and soft-spoken, and you never acted conceited. In fact, I was surprised to discover how shy you were. You never talked much, and you needed to be reassured of my love over and over again when you took me in your arms and kissed my lips or the back of my neck.

I used to think, “Can’t you see, darling, what your kisses are doing to me?” Your gentleness was almost unbelievable. The better I got to know you, the more I knew how well worth loving you really was.

“You have a crazy smile,” I used to tell you.

“Crazy? What do you mean, baby doll?” you’d answer.

“Oh—just crazy,” I’d laugh.

And you’d cup my face and look seriously into my eyes and say, “Is this crazy, too?” and you’d put your lips on mine.

You took me with you everywhere, Elvis, even when you went to buy a new suit. You said you wanted me to help you pick one out. But you attracted such a crowd that we couldn’t remain in the store, so you grabbed me by the hand and we ran out by a side door.

When our wonderful days in Vegas were over and you left for Hollywood, I wondered if our romance would continue. It was one thing to be your girl in Vegas, but in Hollywood where there were so many beautiful starlets, would I still be your Number One girl? I wondered. Then I learned that you were going to Hawaii. My heart sank. There are so many beautiful girls there, and there’s also a magical moon in Hawaii. I was afraid you would soon forget me.

One day my phone rang, and you were on the other end, saying, “Hi, know who this is?” I did but I pretended I didn’t. I said, “I know lots of boys with Southern accents.”

You laughed—and I loved the sound of your laughter. “Baby doll, you wouldn’t fool me, would you?” you said. And you told me you were back in Hollywood and asked when you could see me.

I was coming into Hollywood anyway, to make a test at 20th Century-Fox. We made a date to meet in your suite at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.

When you opened the door, you grabbed me and kissed me and I knew then that you had thought of me in the same way I had thought of you.

I wondered if you would think I was plain. In Las Vegas I had worn lots of stage make-up, since I had to be ready each night for the show. Now my face, in comparison, was almost innocent of makeup.

I shivered a little, fearing that when you took another look at me you would be disillusioned. Perhaps you were attracted to me because I looked more showy and glamorous then.

Instead you said, “Honey doll, it’s good to see you without all that stuff and goo on your face. You look even prettier than ever.”

A shining knight

You had a beautiful suite at the Beverly Wilshire, filled with antiques and a dining room that had a round, impressive dining table. You sent down for dinner. Then you sat at the head of the table, I next to you, and your boys all around us.

I had to giggle at the sight of you so completely surrounded by your retinue. “If this doesn’t look like the Knights of the Round Table,” I laughed. You threw your head back and roared. I tried to imagine each member of your bodyguard in a role as one of the knights. At this point my imagination almost failed.

I giggled again. For on your fine china plate, on the elegant dining table the piece de resistance was—a bacon sandwich!

But in a moment I was transported into thinking maybe I was just like a queen. For you said, “I missed you and thought about you all the time since I left Vegas.”

You told me that you had to be in bed by ten that night, for you had to be on the set early for King Creole. You played some of the tape from the picture and I sat by you on the sofa, listening to your voice singing the songs from that picture. I thought of the girl you’d be singing them to in the picture and my eyes might have turned even greener with envy, but your arms were around me. You were very affectionate. Remember? You teased me playfully, tugged at my hair and nibbled my ear. Each time you touched me, I felt the same electric tingle I’d known the first time I saw you walk into the lounge in Las Vegas.

A make-believe romance

The next night I came again, and together we read your scenes for the next day. It was a love scene and secretly I thrilled to every moment of it, but suddenly you roared with laughter because we were so serious about acting out that make-believe romance. That broke us both up and we sank on the sofa, laughing. How satisfying it was, though, in between the wild laughter, to be in the magic circle of your arms, pretending I was there only because I wanted to cue you on your lines.

And you knew and I knew that it was a real emotion and not just an acting one that we were going through. It was wonderful to know that every time you touched me it was not just because the script called for the gesture, but because your heart and mine called for it.

You said you wanted me with you on the set, and I was there, from early in the morning until late, watching you before the cameras, having lunch with you, going home with you. Then one night you took me to the Moulin Rouge. Sammy Davis, Jr., was the star, and he did a great take-off on you. And who laughed the loudest? You did, darling. You have always been such a good sport.

Perhaps I should have had an inkling then that your love would be hard to hold on to, for all evening long girls came to the table asking for autographs, looking at you, ogling you with eyes that were as warm as a caress. I told myself fiercely that I was your girl—that none of the others were, but I wondered how long I could hold on to a man so desired by so many.

The longer I knew you, the more I loved you, for I saw more and more of your great qualities. Often you talked of your mother, whom you adored. And I thought, How wonderful it would be if he would propose some day. A man who is so good to his mother would just naturally be a wonderful husband.

One day when I had a date with you, Elvis, I noticed that you looked very troubled.

“What’s the matter, darling?” I asked.

You told me that you were going into the Army soon. You knew it was your duty and you weren’t complaining about that, but you wondered if your fans would still be as devoted. “Will the kids forget about me?” you asked in a troubled voice. “There are so many other guys around now—Tommy Sands, Ricky, Gary Crosby. I’m worried. . . .”

“But there’s no one like you, darling,” I said—and I meant it. “No one who has ever known you—even on the screen—can ever forget you.”

And I thought to myself: “And to one who has known the reality of you—your warm arms, your thrilling lips, your wonderful faith and kindness—the memory of you will always be even more unforgettable.”

I knew in that moment that not only would I never forget you but that also I would never in the future be able to recapture with anyone else the feeling of touching the stars that I had when I was with you.

Love—long distance

You were at Fort Hood, in Killeen, Texas, when next I heard from you. You had called me on the phone long distance.

How happy I was to hear your voice! I’d read in the papers that you’d seen Anita Wood at the Base, and I couldn’t help feeling envious and fearful. Did she mean more to you than I did, I wondered?

“I wish you were here with me in Texas,” you said.

“Do you really mean it?” I asked. “Wouldn’t it be embarrassing to you? After all, I read that Anita Wood came to visit you.”

You said, “You know, baby doll, if any girl means anything to me it’s you. No other girl understands me the way you do.”

There were other calls. I remember them so well, as though I can hear them now even though you’re so far away. They’d go like this:

“Hello, sugar . . . know this voice?”

And I’d say, my heart leaping: “Only one boy talks like that.”

You’d laugh and twit me: “You’re sure that of all the boys you know with Southern accents, this voice belongs to just one?”

“Yes, I know your voice, honey. But Elvis, why are you calling me? I read you were engaged to Anita.”

“That’s nonsense,” you said. “Honey, that’s not so at all. You’re very special to me. I love you, baby doll. . . .”

One day your voice over the phone sounded very unhappy.

“Mom is ill,” you said. “Mom and Dad are living here with me. I rented a home outside the Army base and we’re all living here together. Mom may need an operation, and she’s leaving for home today. Dad’s going with her. I feel so helpless. All I can do is pray.”

“I’ll pray for her, too,” I promised. “I’ll count every bead on my rosary and pray to the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, for her.”

“Thank you,” you said. “I hope God will answer our prayers. She’s so wonderful. I hope He won’t let her die now, when I can do so much for her.”

You promised to phone me soon, but you didn’t. I was worried. Days passed; then a week end, and still no phone call. I had to fly home for my parents’ thirtieth wedding anniversary. I was disturbed all the day—you hadn’t phoned.

In New York, we were so busy celebrating I didn’t even glance at the papers, and didn’t listen to the radio.

Friday night, we were all together for a family group picture when my mother said, “It’s too bad about Elvis’ mother.”

I was aghast. “What happened?” I asked.

“Didn’t you know? She died last night. Elvis was by her side.”

I had never met your mother, but you had often talked to me about her. You had told me then, “My Mother will like you—some day when I came to Texas. You’d told me then. “My mother will like you—because I do.”

Now I knew that I’d never see her. And I knew what agony of unhappiness you must be going through. I ran to the phone and tried to call you, but I couldn’t get your number. I sent a telegram to Memphis.

ELVIS DARLING: JUST HEARD THIS MINUTE ABOUT THE DEATH OF YOUR MOTHER. DARLING, IT’S HARD TO KNOW WHAT TO SAY AT A TIME LIKE THIS. MY MASS AND COMMUNION THIS SUNDAY WILL BE OFFERED IN HER BEHALF. IF YOU WISH, PLEASE CALL ME AT PEARL RIVER, BUT I’LL UNDERSTAND IF YOU DON’T. LOVE, KITTY.

No word from you

It was easy enough to say that I’d understand, and I meant it when I wired it, out when days passed without any word from you I grew upset.

Was our unfinished romance finished?

No call came. I flew back to Hollywood, and the moment I got into my apartment I heard the phone ringing.

“Where’ve you been?” I heard your voice say.

I was shocked to learn you hadn’t received my wire to Memphis. Back at your Army base, you were taking your mother’s death very hard.

“I’ll be leaving with my Army unit in a few days,” you said. “Won’t you come to Texas and be with me for the little time I have left?”

“Yes, darling,” I said. And I caught the next plane to Dallas. You were on duty, but your father and cousin Gene met me at the airport.

“So you’re Elvis’ girl,” said your father, and my heart swelled with pride and happiness. We walked into your house and I met your grandmother—kindly-faced and dear. She looked me over with approval. “You must be Kitty,” she said. “Make yourself at home. Anything I can do for you just let me know. We’re so happy to have you here. My boy will be awfully glad to see you.”

I remembered what you’d once told me: “My mother will love you because I do.” And now with your mother gone, your grandma had welcomed me warmly because of you, and she felt I could bring some happiness and comfort to you. With the greatest kindness, she showed me to the master bedroom where I was to sleep. “Elvis will sleep in his daddy’s room.”

Later you took me into your arms; then we went into the living room and talked. With your Army crew cut you looked like a little boy. And when you began to talk of your mother, there was the heartbreak of a lost child in your voice.

You unburdened yourself

Somehow, you felt like talking that evening. Usually, you don’t say much, but as we sat beside each other and you held my hand, you talked on and on, as though you were unburdening yourself. You told me how you’d been at the Army camp when you got a call from the doctors in Memphis that your mom was very sick.

At first, your Army superiors weren’t going to give you leave. You talked to them earnestly, reminding them that you had done KP and everything you’d been asked to do. And you’d told them hysterically, “My mother needs me. And I’m gonna go off to see her whether you give me leave or not!”

You told me how you rushed to see her at the Memphis hospital. Knowing how racked by illness your mother’s body was, your father wanted to direct your attention to something beside her wasted form.

“Look at her eyes,” he suggested. And you did. Her eyes had lit up when she saw you, and it was that look of ecstasy your father wanted you to see. He wanted you to know that you’d brought peace and happiness to your mother in those final hours. Your mother whispered, “Son, you’re with me, Thank God!”

Still, you didn’t think she’d die. You stayed at her bedside for hours. She looked more peaceful, and you thought perhaps she was going to get well, particularly when the doctor said, “Go home, son, and get some sleep.”

Reluctantly you went. In the middle of the night your phone rang. Something ominous in the sound of that ringing warned you that the bell had tolled for someone. In the dark you sat up. You were afraid to answer that phone. But you had to. It was the nurse. “Mr. Presley, you’d better come up here right away. . . .”

You threw on a shirt and slacks and drove there. You ran up five flights of stairs to get to her side. From the other end of the corridor you heard a scream of anguish from your father, and you ran to him. He said, “You’re too late, son.”

When you told me about it, you looked like a child who has lost everything. I put my arms around you and tried to console you.

The tenderest night of all

Then you saw I was crying, too. You enfolded me in your arms and said, “I have never known any girl as tender and sweet as you. I know now how you feel about me. You know how I feel about you, don’t you?”

Later, we went outside on the porch, and hundreds of girls were screaming near the house. I said, “Elvis, even here your public is waiting.”

You answered slowly, “I was so afraid that they would forget me, but now it doesn’t seem to matter whether they forget or not. Now all I can think of is my mother—and how I’ll never be able to do anything for her again.”

“You did all you could, honey,” I said. “She’d want you to forget your grief, and to make the most of your life.”

That was the tenderest night of all, darling. Later you said, “It no longer matters who else remembers me and who forgets, but will you remember me, Kitty darling?”

“I’ll never forget,” I vowed.

And you said you’d never forget me. If possible, we promised each other, we’d meet again in Europe in the Spring. I will be in Madrid with a show. “We’ll meet in Paris,” we promised. And I can’t wait. . . .

Do you still love me, Elvis? You always said you never were one to write letters. And Germany is very far away, so I listen in vain for the sound of your voice.

The memory of the stars we touched and the love we felt is always in my heart. Is it in yours? They—those European girls—are so close, and I’m so far away. But Elvis darling, try to remember—try to keep me in your heart as I have kept you in mine.

All my love,

Kitty

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1959