Call For Joan Caulfield

“Oysters ordered the honey-colored blonde of the superior waiter at a swank Strip restaurant.

“Make it three,” said one of her two male companions.

When the waiter placed the oysters on the table, the blonde pierced the first one laid before her—and gave a smothered shriek.

“Look—a pearl!” she whispered to her two companions. Sure enough it was one—big, too. “Maybe there are more,” she hoped aloud . . . and finally she had unearthed two more. This sent the trio into an electric huddle of secrecy.

“Gotta keep the pearls hidden from the management!”

“Joan found ’em—they belong to her!”

“Ixnay—the aiterway!” warned the girl in pig-Latin as the waiter approached. This went on for the duration of lunch. They were an hysterical trio of Musketeers, guarding their jewels. After lunch they rushed into a taxi and up to the nearest fine jewelry shop. And here a gray-haired, morning-coated jewel expert told them the sad truth.

“Sea-gravel,” he pronounced. “Found in oysters everywhere. Worthless.”

The three Musketeers sagged out, despondent. But at least their consciences were clear. They hadn’t cheated the restaurant out of a thing!

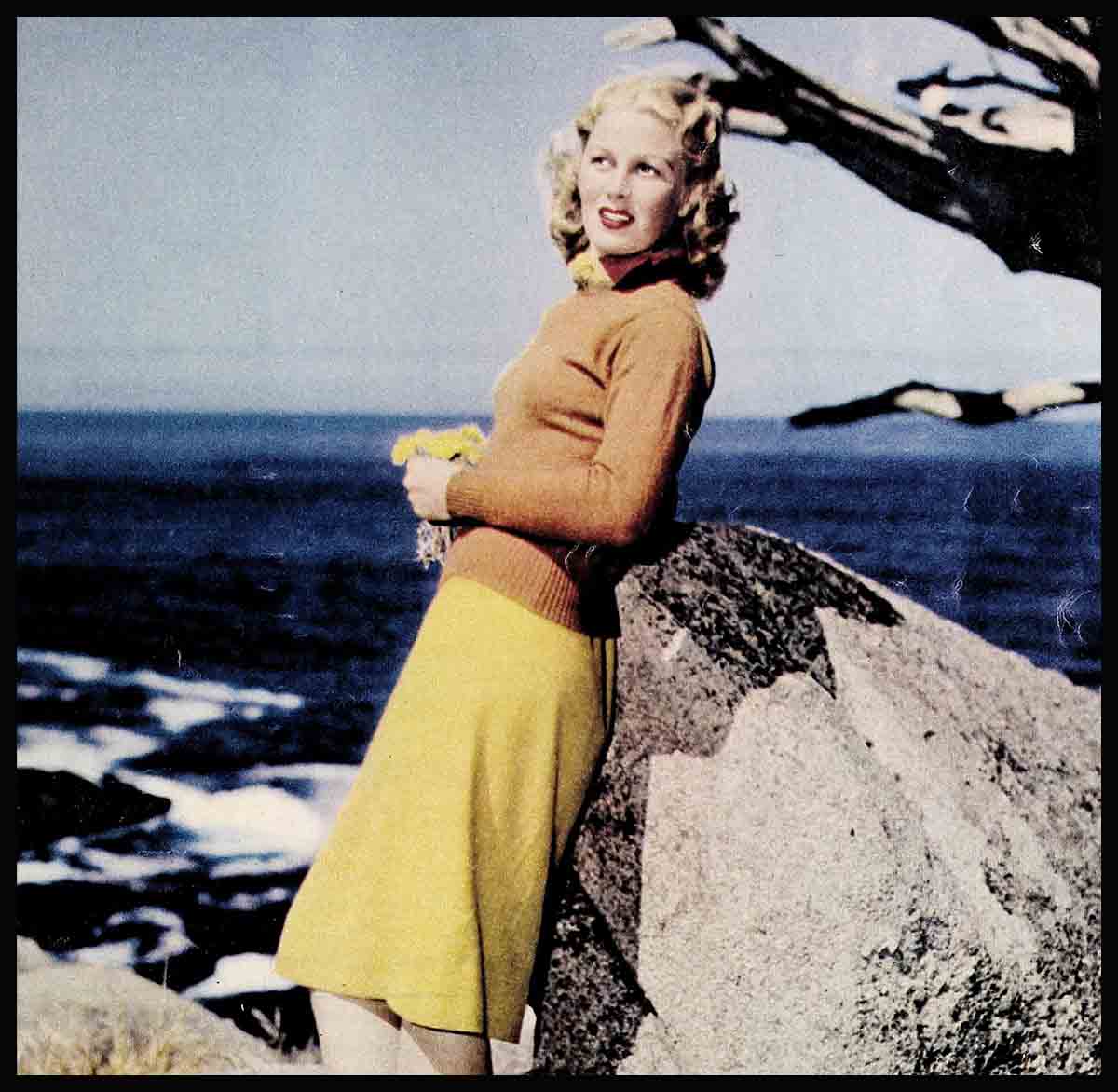

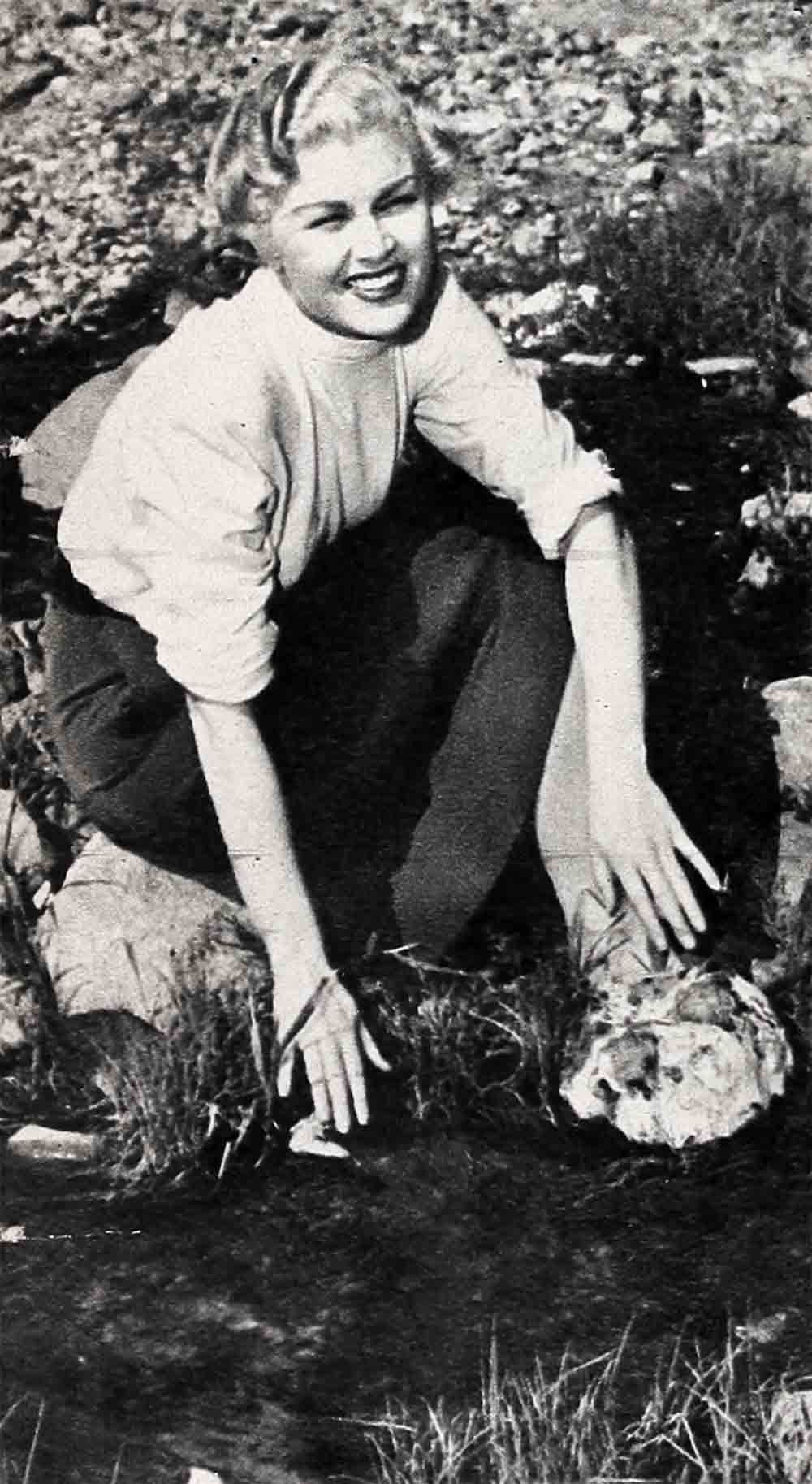

There is nothing sophisticated about that story, and its heroine could easily add the initial N to her name—N for Natural. For natural is the word for Joan Caulfield, which you know if you’ve seen her in her first three pictures: “Miss Susie Slagle’s,” with Sonny Tufts; “Blue Skies,” with Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire; and “Monsieur Beaucaire” with the one and only Bob Hope. She has thick springy blonde hair, wide blue eyes, a wider white smile and a very fine figure which measures a trim five feet five inches.

She is subject to all the usual human aberrations. One evening not long ago if you had been standing in line for a ticket at the Normandie Theater on East 53rd Street in New York, you would have noticed a brunette and a blonde come striding up, unglamourously togged out in flat leather moccasins, checked coats and (revealed under the coats) sweaters and skirts. No hat, no gloves—but suddenly an awful lot of giggles.

Because the blonde stepped briskly up to the ticket window, said, “Two tickets, please”—and then, scrambling wildly around in her purse, she suddenly backed away and shrieked, “Horrors! I have to go home first and get some money!”

At this the two girls went into hysterics. They staggered up the street clinging to each other while they shouted with laughter. Shortly they returned more composed and bought their way into the theater. The girls? One was Joan Caulfield, movie star, and the other her best friend in New York—Patrice Munsel, young and beautiful Metropolitan Opera singer!

But none of this perfectly normal behavior on the part of a famous young lady amazes Joan’s family . . . probably because her family is responsible for the whole thing. No Caulfield could possibly get away with anything but natural behavior. There are too many other Caulfields sitting around demanding their rights—and airing their senses of humor. To hastily introduce the Caulfields, they are:

Mr. Henry R. Caulfield plays the role of father. He is a pleasant businessman, comptroller of a New York aircraft company, and he was utterly unaware of the theater until his offspring got into it.

Mrs. Henry R. Caulfield, a charming woman who never had a career.

Sister Mary (age twenty-five), now Mrs. David Parker, who works for American Airlines in flight planning.

Sister Betty (age twenty-two), who’s Joan’s sidekick, fellow actress and the source of continual family upheaval.

And Joan herself (age twenty-four), who does her own bit toward family upheaval.

The Caulfields now have two homes, one in New York City, which is headquarters for Father Caulfield and any other Caulfields who happen to be in New York acting or vacationing or just living. The other is in Hollywood, California, and is Western headquarters for all Caulfields. They keep in constant communication by telephone—particularly to register outrage over something the other camp has just done. For instance, one magazine interviewer somehow twisted around an interview with Joan and stated that her family dominated and tyrannized her. In general Joan was pictured as a Cinderella fighting wicked relatives in every direction.

No sooner was the article printed than Joan’s telephone in Hollywood began to ring menacingly. Every time she picked it up another pained Caulfield voice said bitterly into the other end of the wire, “It’s all right for you to get ahead, Joan; that’s okay. But kindly don’t use us as goats. We resent it!”

“Maybe you’re a star,” the voices told her, “but we’re still alive back here and certainly kicking—in our unimportant way.” And so on far, far into the night. Since it was not Joan’s fault, she did her own shouting into the telephone . . . and ever since, at every interview, she’s been at pains to underline the unvarnished truth about her very active family.

Until eight years ago, the Caulfields lived outside of New York, in West Orange, New Jersey. Here Joan was born, and here she went to school at Theodore Roosevelt Junior High School and at Miss Beard s School. All this time, she acted enthusiastically in school dramatics—much to the careless amusement of her untheatrical family. Summers the family migrated to Spring Lake to their summer home, where Joan recaptured their respect by winning tennis cups in all the matches.

But when she was sixteen, the entire family moved to New York, and Joan really began coming into her own. She went to Columbia University, where she spent two and a half years acting with intensity. Afternoons, she began easing over to Harry Conover’s Model Agency and landing herself very fine modeling assignments—mainly in the field of mail-order catalogues. But also in fashion advertisements . . . and finally in four Life Magazine layouts and one Life cover!

It was the week that she was on the cover of Life that she dexterously turned her own life upside down.

She was having a coke between modeling assignments with her friend Leila Ernst, who acted in George Abbott shows on Broadway. Huddled over the drugstore soda fountain, Leila spoke of the glories of the professional stage. Joan had never before thought of herself as a real actress. But suddenly she determined to walk into George Abbott’s office and demand a job—now, while she hadn’t given the terrifying idea a second’s thought.

She stepped hurriedly out of the drugstore, paused at the nearest newsstand and bought a copy of Life Magazine—with herself on the cover. Then she rushed over to George Abbott’s office. Gripping the magazine cover-side-down under her arm (in her confusion) she asked the receptionist for a chance to act and an appointment with the famous director.

“Any experience?” said that lady.

“Well, not professionally,” admitted Joan.

“Sorry,” said the receptionist.

“Wait!” shouted another voice—Mr. Abbott’s secretary, who had been peeking at Joan through a half-opened door.

So Joan got a chance to recite lines before the Great Man. It wasn’t until she was out on the sidewalk again that she remembered she’d forgotten to flaunt her picture on Life Magazine! She’d kept it concealed under her arm for the whole performance.

However, she got the job anyway . . . a small underwear-wearing part in the musical “Beat the Band.” In it, wearing scanty panties, a bra and a transparent negligee, she appeared briefly but to the point. But ahead of time, she said nothing to her conservative family either about her costume or the “sexy” walk she had rehearsed in the alley back of the theater.

The result was that the entire Caulfield clan turned up for the trial run in New Haven without the faintest idea of what their namesake was up to. However, they still felt the sheepish foreboding that any healthy family feels for the member who might make a fool of herself any minute now. They shuffled into their seats and sat down in a tight, nervous knot. Shortly their relative appeared, almost as they had glimpsed her in the bathroom at home. They were horrified—particularly when a whole claque of Yale freshmen began chanting, “Boy, what a babe! Boy, what a babe!”

Then Joan’s little sister Betty asserted herself to save the family honor. Indignantly she shouted, “That’s no babe—that’s my sister!”

Naturally, this brought down the house. As every head in the audience swung their way, the Caulfield family’s disapproval shifted at once from Joan to Betty. They didn’t speak to her for the rest of the evening. For that matter, Joan had a hard time getting them to speak to her later on—but finally she convinced them that good theater demanded a girl’s figure as well as her mind.

It was a good thing she succeeded in broadening their outlook, because her next role on Broadway had her pretending to be an illegitimate mother for fourteen months straight. She was the lead in the hysterically funny comedy “Kiss and Tell,” playing the dizzy role of Corliss Archer. When Paramount snaffled her away from New York for a Hollywood contract, her sister Betty stepped into the Corliss role, so as one Caulfield arrived in Hollywood, another kept the family name in lights on Broadway.

In Hollywood, Joan and her mother rented a four-room furnished apartment in a building boasting a tennis court and swimming pool. Here Joan set up pictures of the Caulfields in every room, moved in a new victrola-radio, and settled down. Around home she invariably wears a cerise housecoat and scuff slippers; outside she’s almost invariably in sports clothes. She jangles two gold bracelets on her right wrist, each bearing a gold medal. One medal says: “Miss Susie Slagle’s” and the other “Kiss and Tell.”

In the two years she’s been a Hollywood citizen, she’s been out with many Hollywood men—but her two pet dates of an evening seem to be actor Stirling Hayden and dialogue director Jimmy Vincent. Her daytime dates—always on a tennis court—are Billy Bakewell and Major Martin Work. As far as that saying goes, “the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach”—Joan twists that to mean that the way to her heart is through her stomach! With this in mind, she demands dinners at her favorite places, which are French and Chinese restaurants. After that she drags her dates home to prepare deliciously complicated desserts like Cherries Jubilee or Crepes Suzettes. She can’t cook anything simple. Or non-fattening.

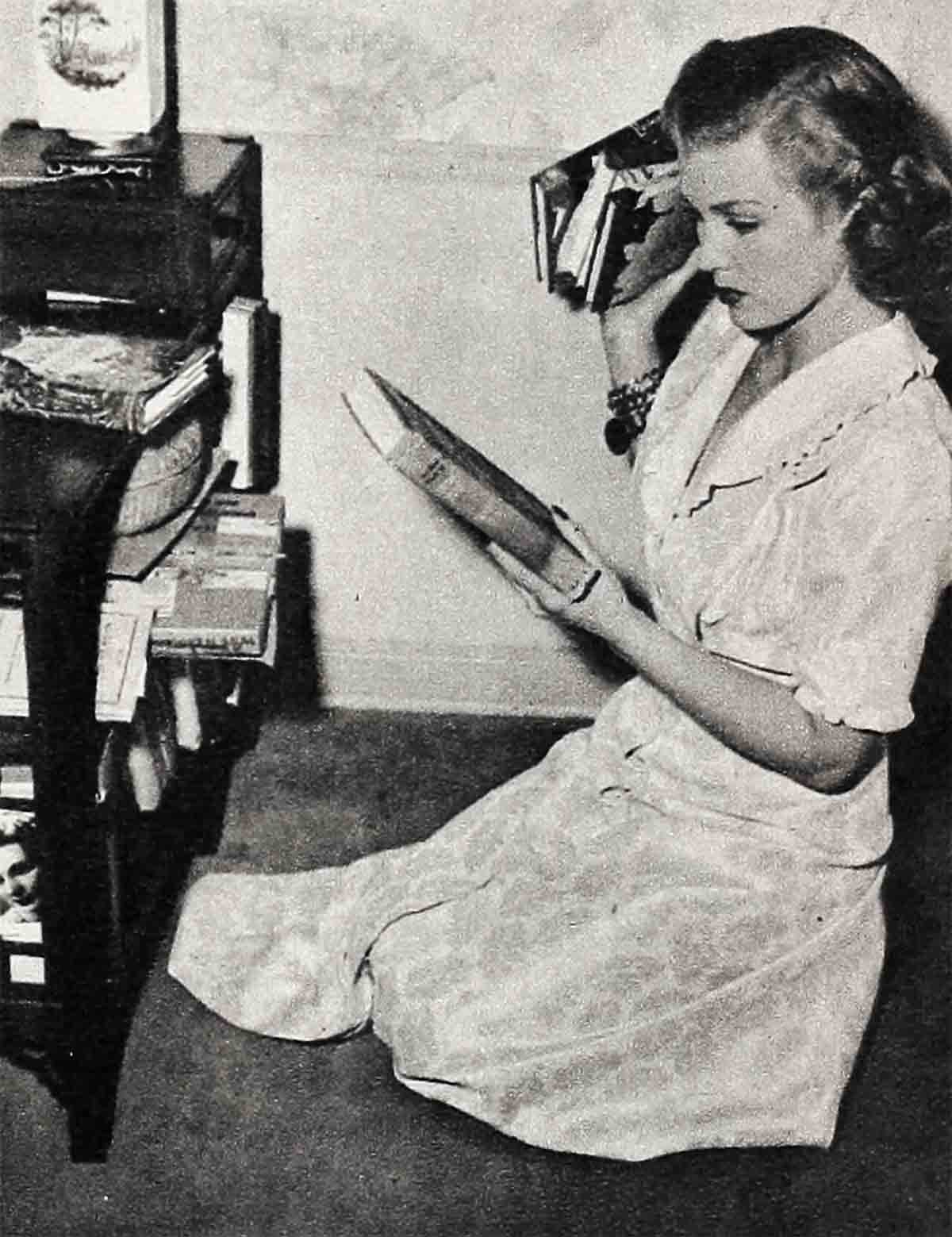

She’s a renegade about the comic strips; she won’t read ’em. But her nose is generally buried in a best seller, or a Thomas Wolfe book. She drives (terribly) a green convertible to and fro, nearly always carrying on a loud argument or two with truck drivers who get in her way. Someday she’d like to be hemmed in by a husband and children, with her career present only if it fits into her home life. She despises shopping for clothes, so her mother shops for her. She won’t take time out for naps, so saves time by lying for a few minutes with her feet higher than her head—then, full of pep, takes a long walk.

There’s only one trying trait to be found in Joan, according to her family: Her love of lovely smells. When she dresses for a date, she pours a whole bottle of pine oil in the bath, douses herself in a flower eau de cologne, finishing off with ginger-smelling bath powder. And dressed—she saturates herself in French perfumes.

“By the time I get into the living room, ready to go, I smell like four hot-houses rolled into one—and my family is asphyxiated and screaming!” laughs Joan. “They usually make me wait outdoors until my date arrives—and then talk me out of using any perfume at all for a month.”

But if that’s her only fault, nobody’s complaining. Except the Caulfields. They have to live with her!

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1947