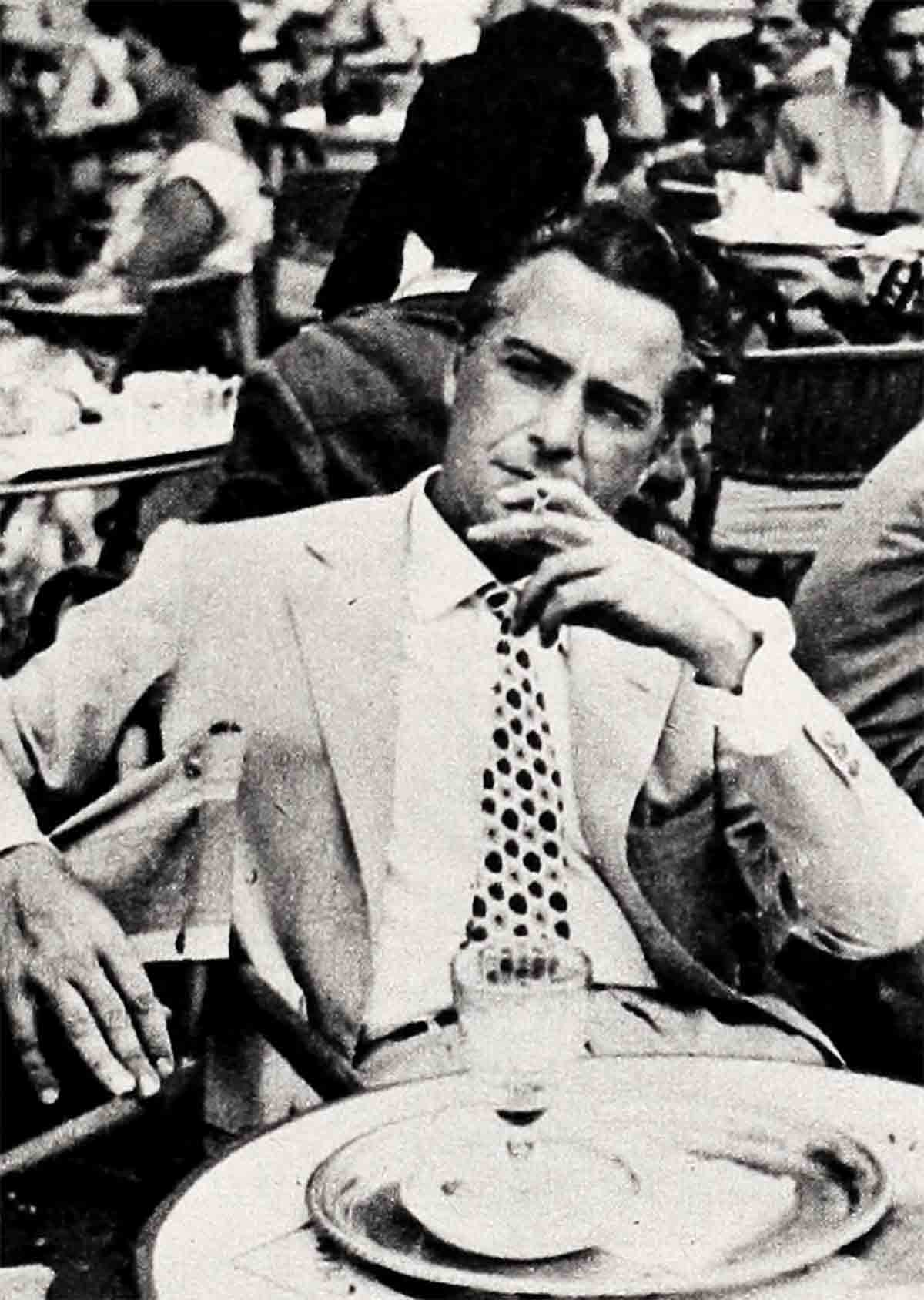

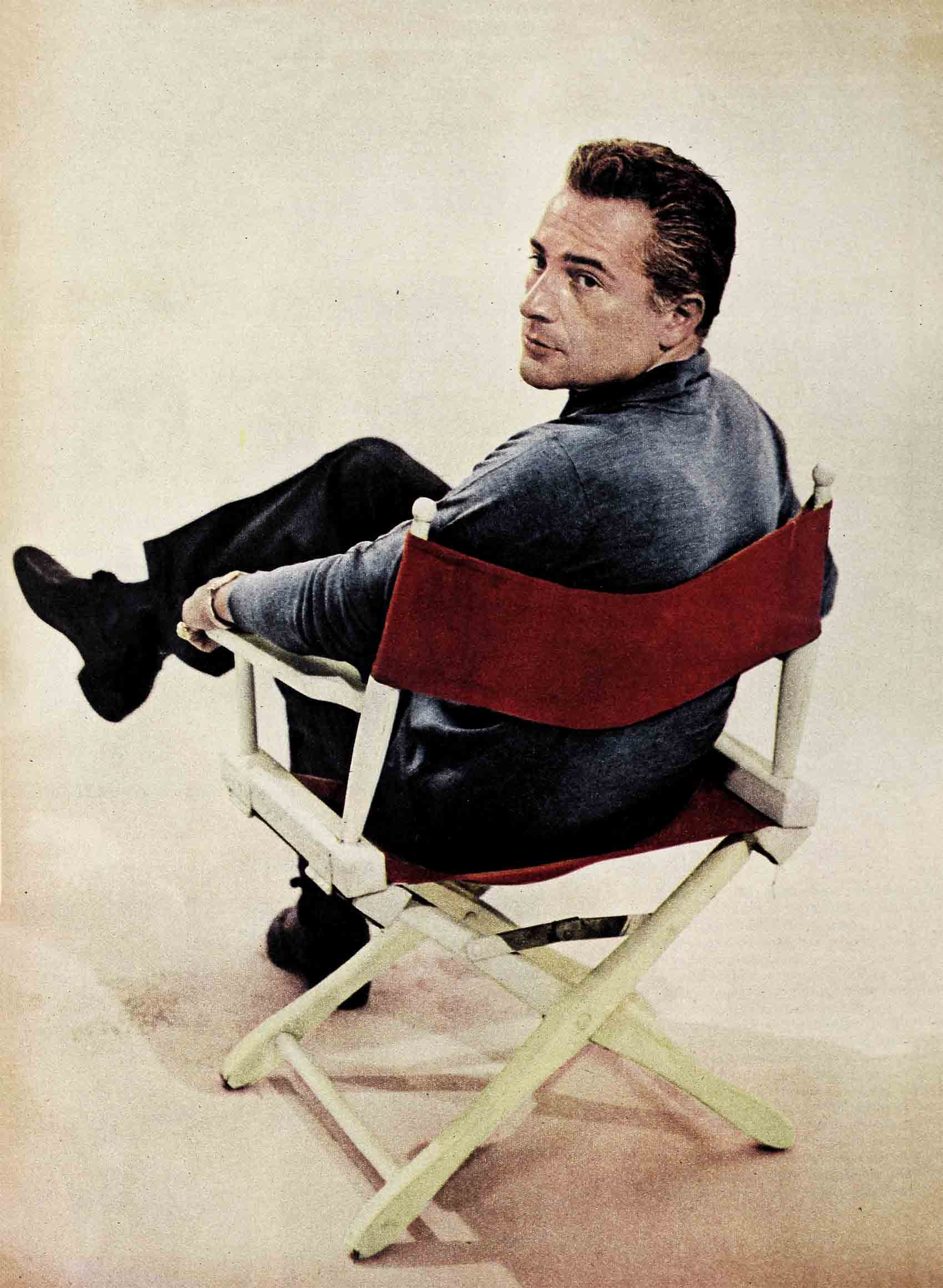

Continental Charmer—Rossano Brazzi

He was Italian and he was polite. “No, no,” he insisted, “there is no great difference between your people and mine. In Paris, England, Germany—yes, there I see a difference. But Americans and Italians—and Spaniards, too, I think—we are very much the same.”

He was in America; he had been here before. And as he strolled the busy streets of Manhattan, he marveled at all the wonders to be found in the biggest city in the world. The rest of humanity kept whizzing by on a treadmill.

Suddenly, the stranger stopped in his tracks—and pedestrians piled up behind him like racing cars on a speedway. He smiled, shaking his head in sad incredulity. “I walk on the street here,” he said. “Honestly, I get tired myself just watching the people rush.”

He had stopped, however, not to rest but to develop the notion that had just occurred to him.

“I think perhaps the main difference between Americans and Italians is the timing and the approach to life. In Italy, for example, a man is going to work. He must be there at nine o’clock—the same as here. Unlike the American, however, who allots himself just three minutes to read his morning paper, the Italian may find an article that interests him. If he does, he will give way to the pleasure of the moment and—who knows?—maybe he does not get to work until nine-fifteen.

“In the same way—here, a man works so hard that at night, he must take time off to enjoy himself. And then, he must plan what he will do for a good time.” The stranger shook his head, tactfully sympathetic. “Americans talk so much about having fun! In Italy, on the other hand, a man tries to enjoy himself the whole day long. He, too, can work hard—if he enjoys what he is doing. And then, in the evening, when people get together, nothing is planned. That way, fun has a chance to develop of itself.”

Then, adding in some amazement, “Here, there are so many beautiful women. At five o’clock, you stand outside the Plaza and you see them go rushing by. Or the other night, at a big party I attended, there were maybe twenty beautiful women there. Really, a man does not know where to look. Young, old, it makes no difference. Here, they are all beautiful!”

In the minds of many Americans, Italy is romance. But the Italian himself doesn’t think of himself as romantic, not until some American comes along and tells him he is. So, Rossano Brazzi, a true Italian—born in the ancient university city of Bologna on September 18, 1918—didn’t set out to be a great romantic star. He just set out to enjoy life. Since a man must work, at an early age he chose the profession he thought he might enjoy most—the law. During his student years, however, he became a boxing and tennis champion, as well as a professional football player. In fact, he enjoyed sports so much that he almost gave up the bar to remain a professional athlete.

Since he once studied singing for two years but gave it up because “you have to be in training, like an athlete,” one gathers that he also decided against sports in favor of the law because the latter interfered less with a man’s natural enjoyment of life. Completing his studies, he took his law doctorate from the University of San Marco in Florence.

In was in Florence that he met his wife Lydia. They married while both were still at school. And it was there that he first acted upon the stage. The play was written and performed by students as part of a school competition. Rossano won first prize as best actor, but he continued his legal studies until he graduated a doctor of law.

“Then I went to Rome,” he recalls. “In Italy, it is necessary to work six months in a law office to get your name in—” he hesitated, “the album?” Rossano toyed with the word, wanting to get it just right. Although his English is perfect, an occasional word still stumps him. It was finally decided that by in the album, he meant licensed or registered.

“Anyway,” he continues, “the office I was working in handled mostly stage people. One day, one of the top directors of the Italian stage saw me in the office. He was casting a play and I was just right for a certain part. That is why he used me.”

The acclaim of both public and critics for his first professional stage performance made the life of an actor seem infinitely more enjoyable than the life of an apprentice lawyer. As casually as he had started acting, Rossano joined the company of the famed Emma Grammatica, who had fallen heir to the roles of Eleonora Duse. Under her auspices, he soon became a star in his own right in one of the most outstanding companies in Italy. In 1937, he played in the first Italian production of Eugene O’Neill’s “Strange Interlude,” and two years later he made his first motion picture.

“And I was a star right from the very start,” he adds. There is no braggadocio in the remark—merely the happy surprise of a man who wants you to know that fortune has been good to him.

In addition to his native Italian, Rossano speaks English, French, Spanish and German—and has portrayed roles in all those languages. Since he first went on the stage, he has appeared in over two hundred productions, playing all over the Continent—including London, where Dame Edith Evans invited him to appear opposite her. What’s more, for the last five years, he has won the award as the best stage actor in Rome.

He has also starred in over seventy-five motion pictures, having made them in Hollywood, Italy, England, France, Spain and South America.

“I used to make as many as eight films a year,” he says, “and that is a lot of pictures. Besides, in Italy, it is different from here. You might get up at six or seven so you can start at nine, but there is no knowing what time you will finish.”

It was inevitable, of course, that Rossano be discovered by Hollywood. In 1949, David O. Selznick signed him to a seven-year contract and brought him to Hollywood. In his first and only film, he played in a remake of “Little Women.” It was one of the first successes of Katharine Hepburn, his current co-star in “Summertime.” But Rossano didn’t play the romantic lead. He played a middle-aged German professor, and his strong good looks were hidden behind a beard. The public was unimpressed, and Rossano—after remaining a year in Hollywood without doing a second film—asked to be relieved of his contract. Sadly disillusioned with the ways of Hollywood, he and Lydia returned to Italy, where he was an established star of stage and screen. Whenever an offer came to appear in another American film, Rossano turned it down.

But then Hollywood came to him! In 1953, Jean Negulesco, the director, was in Rome shooting exterior scenes for “Three Coins in the Fountain.” He talked Rossano into taking the role of the young Italian clerk who works with the American government agency. Since most of the film was being shot in Rome, Negulesco pointed out, Rossano would only have to spend a few weeks in Hollywood. Rossano accepted. It was to prove a new turning point in his life. With that one picture, he not only established himself as an exciting personality in American films but became one of Italy’s top tourist attractions. Ever since Jean Peters tossed that coin in the fountain and got Rossano Brazzi as the answer to her wish, one of the first things American women in Rome do is ask, “How do you get to that fountain?”

Rossano’s success in this film led to his role as the Count in “The Barefoot Contessa.” And although he proved to be the death of Ava Gardner, many women felt that it was a beautiful way to die. But it was not until “Summertime” that Rossano was given a chance to display in a motion picture the versatility that had made him Italy’s top actor in the theatre. And it was not until he and Katharine Hepburn reached for a fallen gardenia in the dark waters of a Venetian canal that American audiences fully understood why, for years, Rossano Brazzi was known as “the Clark Gable of Europe.” David Lean, the director, who knew of Rossano’s ability, dispensed with the formality of testing him for the part. But the greatest tribute to his acting ability came from Katharine Hepburn herself. Shortly after filming began, it was she who insisted that he be co-starred and billed with her over the picture’s title.

As it turned out, they are also sharing rave notices. “Summertime” is so good that even Rossano likes it.

“Always,” he says, “when I see myself in a picture, I hate myself. I want to spit. But this time, it is different. I have seen ‘Summertime’ four times already and I could see it again tomorrow. That is because of the story. A picture is only twenty-five per cent the actor, but seventy-five per cent the story.”

He even likes the beginning, which some have criticized as slowing the pace of the picture. “But that is Venice,” he says—only when he says it, it’s Venezia—like a song. “It is lazy, like a gondola.” And it is the best explanation yet of why Venice is the city of romance!

Rossano still lives in Rome, as he has for the past fifteen years. There, in the center of the city he and Lydia occupy a penthouse apartment—along with five dogs and three parakeets that they never travel without. Living a completely unplanned existence, they seem to have time for everything. Rossano is still a sporting enthusiast, going in for tennis, swimming, boating, soccer, hunting, racing cars and walking. The last is something new, but as he explains: “Rome is the only city where I walk, and there it is mostly at night. But now I know the city. I love it—particularly by moonlight.”

He does not make nearly so many motion pictures as he used to. “I am become more difficult,” he admits, with a happy grin. “You see, I prefer the stage. I am really a stage actor. There, when you get together for rehearsal, it is work. You are yourself. But the movies—one can waste a whole day for something that is forty seconds on the screen. Now, I do not do a picture unless I like the story ninety percent.”

With the success of “Summertime,” however, Rossano is being mentioned for just about every new film that calls for a romantic lead. It is not only a tribute to his appeal but a sign of the times—for, suddenly, in a world hungry for romance, there is a dearth of romantic actors. The older stars are still popular, but they no longer suggest that “wonderful, mystical, magical miracle” that Katharine Hepburn dreamed of finding in Venice. The younger actors are either of the T-shirt, blue jean school, who grunt and paw their way into a reform school as often as they do the heroine’s arms, or the clean-cut young man, with or without horn-rimmed glasses, who suggests all the charm and awkwardness of first love.

It is significant that Rossano, at thirty-seven—an age when most actors are gradually edging their way into character parts—should suddenly blossom out at the peak of his romantic charm.

In a day of sports clothes and crew cuts, Rossano still dresses with Old World elegance. There is a kind of magnificence about him—great stars of the stage used to have it; so have royalty. If he converts you into an enthusiastic fan with the charm of his first smile, it’s because his manner is so flattering.

When he’s late, his little gesture of apology more than makes up for it.

“Excuse me,” he says. “I did not get to bed until four o’clock. Leonard Lyons (the Broadway columnist) was showing me the town.”

What did he think of the town?

He laughs. “I did not see it. Three minutes, here, three minutes there. But Margaret Truman came along with us and I did get to see that she is a very nice person. ‘But why do you photograph so ugly?’ I asked her. She is quite beautiful, you know.

“In Italy, the women are different,” he says. “There, there is beauty, yes, but—” He searches the ceiling for the right word. “But it is—wild. Do you know what I mean?”

The telephone rings, and Eugene Lerner—the young American who lives in Rome, acting as his agent—comes in to announce that it is an emergency. Rossano jumps up excitedly and, with a lightning shrug to the Fates, rushes to answer in another room of his suite.

And then he’s back, with a scowl of black impatience. “In my country,” he remarks, “an emergency is someone is dying. Here, it turns out to be a beautiful girl.”

Speaking of beautiful girls, how did you like Ava Gardner?

“Ava? She is a wonderful companion. I feel very sorry for her though. She is But she doesn’t deserve it because she is really a very good girl.”

And Katharine Hepburn?

“A strange person,” he says, “but wonderful when you gel to know her. She has life, temper, feeling. And a really superior brain. The ideas come out from this mind like a river.”

Then, he plunges into the controversy. “This man,” he points out, referring to the married but amorous art dealer he plays in the movie, “he is Italian. In Italy, there is no divorce. But Jane, she is afraid. She thinks it can lead to nothing because she can see the end of their love. This is a mistake, because there is always the end to love.”

But, but . . .

“No, no! I mean the dream of love—the passion. It lasts maybe one to five years. Five years?” he considered this carefully, then shook his head. “I have never seen it last that long.”

But what about your own marriage? You’ve been married fifteen years. Everyone says you and Lydia couldn’t have a happier life together.

“Ah, but when the intensity of love passes, then the other things take over—the things which are more important. Affection, mutual interests. The trouble with many marriages—the first break—it comes when you want to do one thing and she wants to do another. That is when you must both give a little. You get together and see what you can do to enjoy the rest of your lives together. For example, I can tell you: if another woman did some of the things my wife did, I would hate her. But with Lydia—I know what is going on in the back of her mind. I know why she does it. You see, you come to love the defect.”

And as he stopped to consider her defects, his smile grew downright tender.

“You know,” he said, “if I were to marry again, I would marry the same girl today.”

Which perhaps explains Rossano Brazzis charm. In matters of romance, every woman knows he is infallible.

THE END

—BY ED MEYERSON

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955