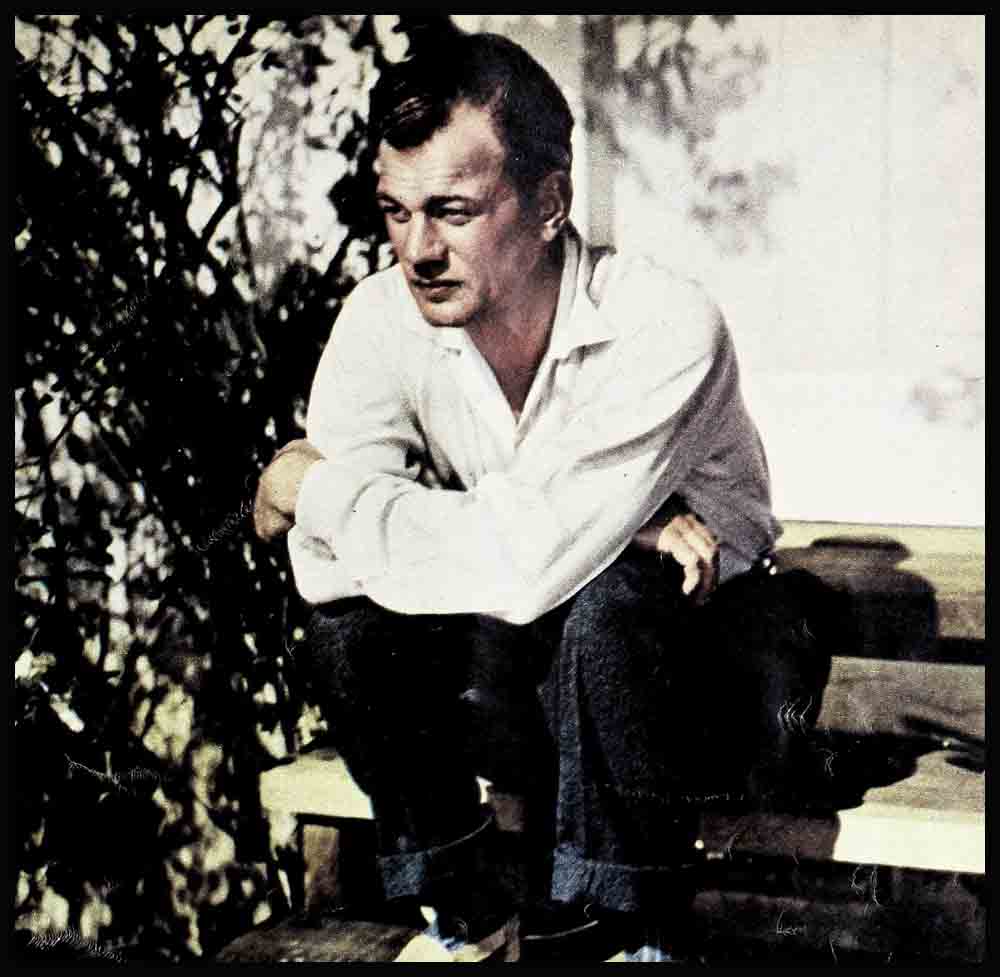

Confessions Of A Lazy Guy

Looking back is an uncomfortable way to realize that one has often been silly. Yet if it’s possible for another person’s experience to guide one (personally I doubt it), I’ll be glad to be silly again here— though I hear in advance my friends chuckling, “Cotten a good example? That’ll have novelty value!”

To get the ball rolling we’ll brief the vital statistics. Born, enough years back, in Petersburg, Virginia. Had the same kind of childhood and family life as thousands of other American kids. My earliest memory is Grandmother, rocking on the porch. Three rocks, a pause, then two rocks: 1-2-3— 1-2, 1-2-3— 1-2. I’ve counted it a thousand times.

Grandmother’s image remains vivid because she was my standby in a difficulty that has never diminished—even as a small boy I always needed money. Her memory deserves to endure because she tried to impart a major secret. . . Each time that her clean, gnarled hands slipped me that needed life-saver (at first a nickel or a dime, then a quarter or a half and later, in high school days, a folded dollar bill) she would whisper, “Go spend this—and watch your time. You can get more money, but not more time.”

How much did I hear of that? Only the magic word, spend. The value of time—the fact that you cannot win any valuable progress you want in life except by working a definite fixed amount of each day’s time—would come to me later.

Meanwhile, I was to make the first Cotten discovery. That came about during The Case Of The Sawmill Hand. Two uncles, one of whom was a part-owner in the mill, conspired to “arrange” a summer job. Three summers I worked in that mill, ten hours a day, for $3.50 a week. I can still smell the fresh-scented sawdust—enough sawdust, it seemed, to stuff all the dolls in the world.

Knowing the family finances weren’t such that I had to work that hard, I grumbled bitterly but silently—and did what I was told.

The third summer I overheard my uncles talking. The one who was part-owner in the mill said, “I know it’s severe, Whitworth, but he’ll be in the habit of working hard when he gets to the University.” They wanted me to be a lawyer and I saw myself (if this mill training was necessary as a conditioner) lugging giant tomes from University library to dormitory and studying all night.

I had heard in school about William Shakespeare—though I hadn’t read his plays, which seemed to me more formidable than even the dreaded law books. If a man could succeed as an actor as Shakespeare did, I reasoned, and yet find time to write that huge, small-type volume, then the acting end must be a cinch. I had the fool’s delusion that being an actor consisted of wearing good clothes all day and sort of showing off, behind footlights, every night.

The first Cotten discovery was creeping up on me: I was lazy. I still am. I’ve had to smack down laziness every day of my life. Between pictures I argue to myself, “You really ought to go away and rest, Cotten—you owe it to your work.” Bunk!

Laziness is mankind’s greatest enemy, and it’s universal. I know that many people keep it down; women who are moved by self-sacrifice to superhuman effort; men who support large families through long bouts of adversity; handicapped people who work as if they had no handicaps, because they refuse to be downed. Only great stimuli—although the habit of work will help—can overcome natural human laziness. If you cherish what you think is an ambition, face this now: You’re lazy; you’ll fool yourself repeatedly that you’re doing all you can; you’ll have to make yourself work—more. Or, if you won’t face that, face this: What you have isn’t an ambition; it’s just a wish.

Did those valuable facts seethe in young Cotten’s mind when he asked his mill-owning Uncle Samuel to stake him to a year in Washington, D. C., so he could study dramatic art? No. I was still in my dream that acting was “Hey! Hey!” Uncle Sam, a real sport, gave up his dream about me—sawmill and law; and I went at least far enough in appreciation, when I arrived in Washington with his money in my wallet, to pay in advance a full year’s tuition.

Then, already a successful actor in my own mind, I proceeded to live like one—accepting treats, treating back, promenading in glad raiment the tailor called suitings. And—I escorted my girl friends nonchalantly to $4.40 down-town orchestra seats.

In six weeks I had scatter-blown my year’s board, textbook and incidental spending money. Then began a series of after-school jobs that gained me an unearned reputation for deserving industry. Among the grubbier tasks was playing substitute center on an early-vintage professional football team which, thanks to my face in Saturday mud, netted me $25 per quarter.

Here we’d better brief some chronology: Going home broke, feeling foolish . . . making a clean breast to my uncle . . . working as lifeguard and night watchman at The Lake, Petersburg’s summer play-place, to pay him back what he’d advanced on my “career” . . . getting fired when The Lake’s proprietor, after a Saturday night dance, found his new watchman asleep! . . . going to New York to wear out shoe leather and return in day-coach style.

Then the Miami, Florida, boom called. Down South I began a round of salesman jobs. They taught me drab but vital facts: If I made fourteen calls a day, I sold more brushes, advertising, paint, real estate or potato salad than if I made eleven or nine calls. Also, I didn’t earn even a passable living unless I worked a full eight hours a day. I’ve never known anybody, in any professional or Creative line, who did!

Varied events propelled me north. The Miami boom crashed, leaving a rising young potato magnate mashed. A charming, good-looking blonde, Lenore Kipp, whom I had met when she visited a Miami Civic Theater rehearsal (oh, yes, I was still butting at the theater!), returned north about that time. Lenore had voiced a smart thought or two in Miami. “Left-handed theater isn’t good enough. Nothing left-handed is good enough,” she had said. Now I told myself, ‘Tm going back to New York. I’ll stick at the theater till I click.”

A friend in Washington gave me a letter to a New York dramatic critic. The latter, eager no doubt to get me out of his office, inquired inclusively, “Whom would you like to see about a job?”

I, still so willing to start at the top, answered, “David Belasco.”

I found Mr. Belasco watching a rehearsal in a darkened auditorium. I slipped him the letter which he was unable to read because of the gloom. A courteous gentleman, he addressed a few remarks to me, even asked my opinion about the happenings on the stage. When the lights went up he had forgotten I was there—yet recalled instantly the critic’s name I had whispered.

“Oh, yes,” he smiled, “a letter from Burns Mantle. What can I do for you?”

“I want a job in the theater,” I blurted.

“Very well,” he replied instantly. “Report Monday morning.”

Belasco’s man! An assured success in the theater! Oh, lovely thought!

Before glimpsing Cotten-with-Belasco, note here that I, by sheer dumb luck, had stumbled onto a useful procedure. It’s useful to anyone wanting to learn any line of work. To all who ask the “How-do-I-get-started?” question I sum up my excellent hindsight:

Expose yourself to the kind of work you want to do—to people who are doing it day by day, practically and with success.

Hollywood abounds in top-rankers who followed the exposure procedure, and who adopted it—on purpose.

Alfred Hitchcock, now the world’s master of suspense, was a fruit-grocer’s small son when he began to admire American movies, and later, at nineteen, he “haunted” the first American producer who came to England to make a picture. The producer finally let him start (this was silent-picture days) by drawing “art titles.” If the hero or heroine was to be depicted as a bit of a wastrel, Hitch, at the foot of the title preceding the scene would draw—original fellow!—a candle burning at both ends. Eventually they let him write titles, and he climbed through much apprentice work to his exciting preeminence of today.

There was a girl, too, who became Hitchcock’s secretary. Poorly equipped for that job—she had to work fast to get started at what she wanted before Hitch would fire her. She did work fast, made sensible story suggestions and advanced them very casually when the boss’s mood seemed right. That girl grew to be the producer of “Phantom Lady” and “Uncle Harry”—lovely Joan Harrison.

Leo McCarey, producer-director-writer of “Going My Way,” worked nearly five years as round-the-set handyman for Tod Browning, a top director of twenty years ago, who had once performed the same chores for the Old Master, D. W. Griffith, director of “The Birth Of A Nation.”

You’ve read, doubtless, that the actors and actresses who seem to last all seem to have had that good fortune of “exposing” themselves to people and surroundings that could teach them. The modern way to start that process is little theater and semi-professional theater work, and chores at your own local radio station. And best of all, the exposure system applies not only to movies but to any field of work.

A young girl just out of high school went to a writer friend of mine and asked his advice on becoming a writer. She could afford no more schooling. He advised that she go to a newspaper or press association and apply for a job as a “copy boy”—available in these times to girls. He told her to say nothing about writing. “Your job will be taking copy from reporter to city desk, desk to composing room chute or to a wire man. It’ll be low in pay. After you’ve been there awhile do one paragraph items and turn them in. Be alert. Then ask if you can try your hand at obituaries. Common sense will tell you other chances to ask for.”

The girl followed his advice. Result: Today she is a cub reporter—on her way toward what she wants.

Returning to Cotten (we almost got rid of that fellow, didn’t we?), it was probably fortunate, though I didn’t know it, that humility or plain scaredness prevented me from saying to David Belasco, “I want to be an actor,” and impelled me to blurt, “I want a job in the theater.”

After a week end of rosy dreams (I think I proposed marriage, but don’t quote me on it) I reported bright on Monday for what turned out to be three jobs. First, I distributed sheets of paper on which were typed the various actors’ parts, and prompted stumblers during rehearsals. In Hollywood we call that script girl! Second, as sound effects chief (and staff) I jingled telephone bells, produced clop-clop for imaginary horses and rubbed sandpaper together to simulate rain. If a Belasco play had trolley cars, Cotten went Clang! Clang! Clang!

In the third phase of my job (call boy) I ran up and down outside the actors’ dressing rooms, knocking on doors and yelling, “Five minutes to curtain!”

I believe Broadway’s dean liked the fact that I didn’t whine. Anyway, perhaps to give me the inner comfort I needed, he let me understudy the juvenile leads in “Dancing Partners” and “Tonight Or Never.” Alas! During my lowly apprenticeship—two plays, two years—neither of those blankety-blank juveniles (and they wore suitings, too!) developed so much as a head cold!

Toward the end of that stretch, Mr. Belasco confided quietly, “Joe, I’m going to use you as the juvenile lead in my next play,”—and again, for weeks, I walked on air. (I’m pretty sure I proposed then.)

Then occurred an event which the theatrical world acutely remembers: Mr. Belasco died.

That time is a blur to me. I was bewildered, literally in a daze, from much more than the whirling uncertainty of my future; I was mourning the loss of a true friend.

Before I had time to begin to think collectively again, I learned that a major Hollywood studio would audition in New York, seeking an “unknown” juvenile for an important feature picture. More than a hundred reported. Through three days we narrowed down—ten, five, three, two, one. I was that one—and did I feel good?

“Only one thing more,” said the Hollywood director who had planed East for the try-outs. “A camera test to be sure you’re photogenic.”

“Great!” was the report on that test. The next day I was to bring pajamas, lounging robe and slippers to act out a bedroom scene, also for the camera.

“Don’t worry,” said the director. “You’re practically on your way to Hollywood.”

Next day I lugged a suitcase across Manhattan.

The studio gateman said: “Sorry, your name’s not on the pass list.”

“But,” said I, “I’m to be the lead in the new picture. I’m to do a scene today.”

He did some phoning, the result of which was, “Sorry.”

I suppose I really appeared more tragic than funny, for he phoned again and the casting director, whom I had barely met, came out, looking kindly and embarrassed, and I caught snatches of: “Long distance . . . called back . . . studio . . . new series . . . plane this morning.”

When the words stopped blurring in my ears, and made a pattern, I asked, “Has his plane left yet?”

The kind man from Casting reached the director for me at the latter’s hotel.

“Yes, it’s true, Joe,” the phone said. “I’m off the picture. Flying back this morning to start a new series. And the new director of this one has a choice of his own for that lead. He’s announcing him in Hollywood today.”

Eager for a crumb of comfort, I finally blurted, “How did I really look in that test?”

“Well,” the director laughed in Jovian good humor, “you did look a little funny, Joe. Your head photographs a trifle egg-shaped.”

Egg-head Joe dragged himself to Lenore’s apartment to break the dirge-like news—and found kindness and faith, as he would on other occasions.

I haven’t rattled off all this to ask you to weep over Cotten. Far from it! Looking back over it now, I think I see a socko lesson for anybody: Don’t believe in luck.

We can wonder what would have happened if Mr. Belasco’s generous offer of a juvenile lead had materialized. Would I have made good, or was Cotten too green to pick?

We don’t have to wonder what would have happened if I had landed that early movie lead; we can be sure. Remember, I had had no professional acting experience whatsoever, and here’s what I would have come to Hollywood without: A year of stock in Boston, which almost immediately followed; the five Cotten Depression years, with the iron self-discipline they made necessary (put in eight hours a day when you’re looking for a job; it’ll pay off in five years and work’s a good habit—I wish I could get over it); several hundred radio performances—mostly at twenty dollars a throw—which I hated and despised, but which later proved invaluable experience; splendid training with Orson Welles in the Mercury Theater and touring the country with Kate Hepburn in the stage version of “The Philadelphia Story”; and a parcel of flop plays that neither you nor many other people ever heard of—thank heaven!

Had I won that early movie lead I’d have fizzled, either in that picture or soon thereafter.

So, I ask you, how can we count on luck as a factor in our lives when we can’t even tell good luck from bad?

Trouble is, if you believe in good luck you’ll believe in bad, and if you count on the one or use the other as an alibi, better start hunting for a diving suit, because you’re sunk.

Did he say sunk? That’s what he said and he knew what he mas talking about, for it almost happened to him. in fact, before he finally got where he is today he hit storms, swift currents and riptides. But let Joe Cotten tell you about it himself. You’ll find the conclusion of this pungent story in July.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945