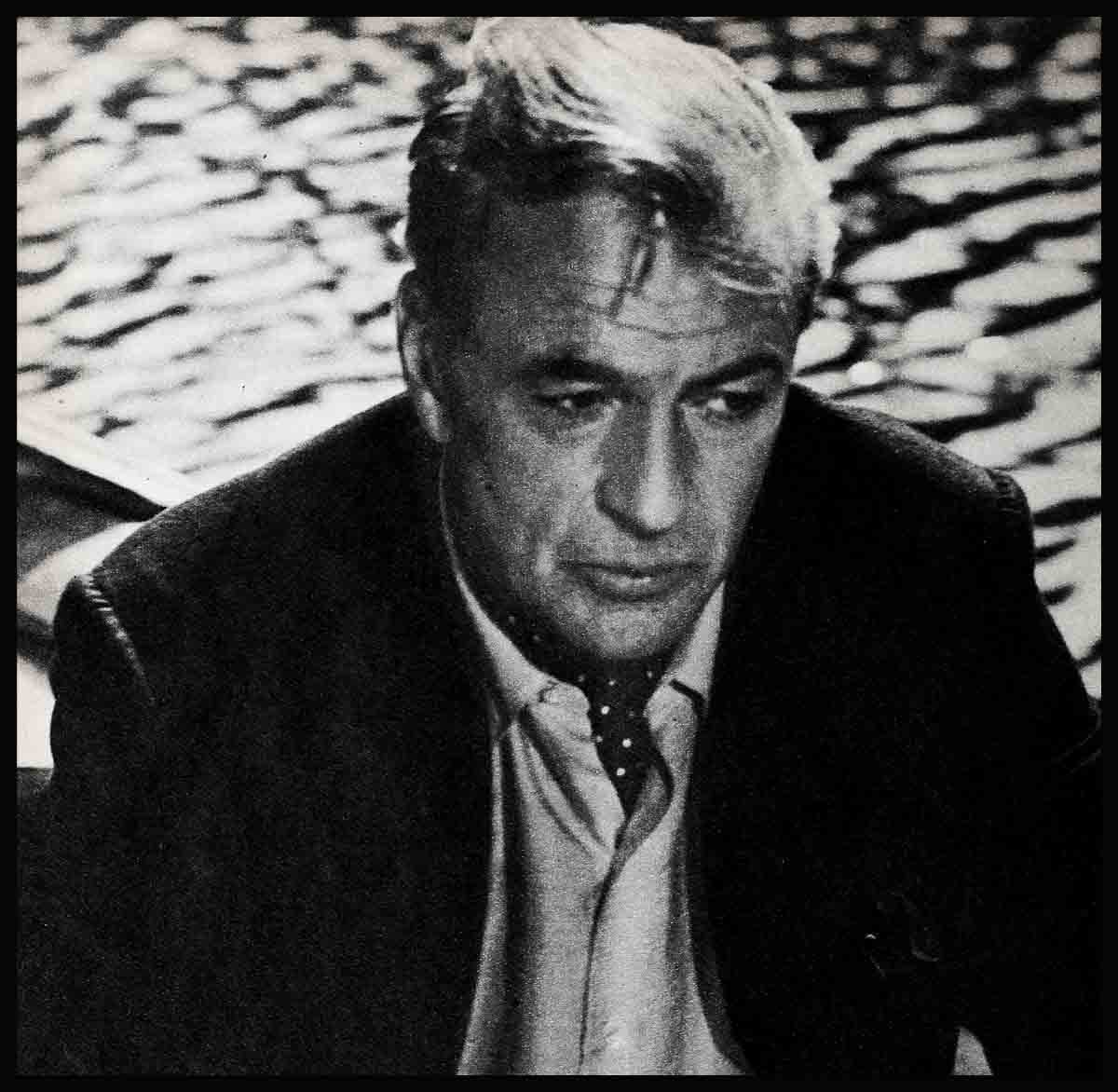

Tribute To A Great Guy—Gary Cooper

“And Coop,” Jimmy Stewart said slowly, “I want you to know . . . that with this goes all the warm friendship—and the affection—and—” The famous voice cracked and broke. The vast audience in the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium sat motionless in stunned silence. Across the country, in millions of private homes people sat wide-eyed. Jimmy went on.

“I am very—honored to accept this award for Gary Cooper. I’m only sorry that he—isn’t here tonight to accept it in person. But I know that he is sitting beside his television set tonight.” His eyes lifted suddenly. In the vast auditorium everyone knew that he had forgotten them, forgotten the cameras. Now Stewart was looking past them, speaking to one man alone. “So, Coop, I’ll get this to you right away, and, Coop, I want you to know this—that with this goes all the warm friendship—and the affection—and. . . .” For a moment he could not go on. Then he raised his head and stumbling a little, finished his sentence. “—and the admiration—and the deep—the deep respect of all of us. We’re very proud of you Coop—all of us are—tremendously proud.”

Then, holding his friend’s Oscar in his hand, he turned and went swiftly off the stage. The applause broke in wave after wave, washing across the footlights, thundering through the auditorium. It poured across the country, into people’s homes and into their hearts. It flooded through a television set turned on in a Beverly Hills home where a tall, gaunt man, painfully propped up on pillows, heard it—and turned his face away for a moment.

Gary Cooper was sick—sicker than anyone but he, his family, his doctor and a few close friends knew. Now, he realized, everyone would guess. And he knew that if they asked him directly what was wrong, he would use the word they so carefully avoided.

“Yes, I have cancer,” he would say.

He’d been telling the truth for so long; he couldn’t stop now.

Why me?

Gary Cooper, lying back against the pillows with his eyes half shut, could not keep his mind focused on the television screen. Something was troubling him. A question. He had been asking it for many, many years. Now, seeing Jimmy Stewart’s tear-filled eyes and hearing the sound of love from the audience in Santa Monica, the question returned to haunt him again.

“Why me?” Gary Cooper wondered. “Why do they care about me?”

Restlessly, he turned his head from side to side, wondering. He was not likely to find the answer. No one in Hollywood was likely to give it to him.

But there was an answer. It was spelled out in the very tissue of his life. It had made him a legend in his own time.

The roots of the legend, of course, lay in his childhood.

He was called Frank Cooper then. To his mother, who came of English stock, a childhood in Helena, Montana, meant that her son would learn how to ride a horse, and rope a steer and little else. She decided he’d be better off in England. When Frank was nine, she shipped him off to the Dunstable Grammar School in Bedfordshire.

When he returned, several years later, he had changed. His Montana drawl had been tightened into clipped British speech. His clothes had an English schoolboy cut. His manners had improved. His teachers, bewildered by the curriculum he had studied abroad, dropped him back a grade into a younger class.

Within two days he was the butt of a hundred school jokes. Boys, who a few years before had been his friends, teased and tormented him. It was a bewildering experience, but he didn’t have time to puzzle it out. He was too busy fighting his way to and from school every day. After a while the boys began to respect his fists, and life became easier.

Now that he had won the right to speak and dress as he liked, he began to ask himself questions. Who was he? Did he really want to be an English schoolboy? His answer was to let bis speech soften again and learn to ride and rope and shoot. He would be what he had been born—a Western youngster.

In his early teens, Frank Cooper suddenly grew tall. He was sixteen when America entered World War I. He was big enough—if not exactly old enough—to quit school and help on his father’s cattle ranch during the manpower shortage. He jumped at the chance. It came as a shock to discover that getting up at five A.M. wasn’t the fun he thought it would be. Or patching range fences at forty below. But for two years he grit his teeth and hung on, till it was okay to quit and go back to school. And he wondered if the years in England had spoiled him after all. If he wasn’t going to be a rancher, what would he do with his life? Who was he?

A future in art?

Now when he was already three years older than anyone in his class, he was in an automobile accident. He emerged with a badly broken hip, another leave of absence from school, and time on his hands. Propped up in a chair, unable to use his legs, he remembered a childhood hobby, called for a drawing board and pencil and began to sketch. He produced some amusing cartoons, and a few recognizable caricatures. Some of the cartoons were political; be sent them off to a local newspaper. They were printed. Frank Cooper decided happily that he had found his vocation at last—he would be an artist.

Soon as he was back on his feet he set out to complete his high school education so he could enter Grinnell College in Iowa as an Art Major.

He liked Grinnell. But at the end of three years, business took his family to California. Frank joined them there for the summer. A look at the bustling community growing up around the movie industry in Los Angeles gave him an idea. He decided to quit Grinnell, get a job as a commercial artist and save enough money to go to a really good art school in Chicago. Full of confidence, he set out to get a job.

He got one, too.

And got fired. Surprised, he went looking for another. The same thing happened. And a third time, and a fourth.

He learned that he was good enough to get a job as an artist—but not good enough to hold it. Seeing his work with new eyes, he came to understand that it would never be quite good enough.

For the third time in his life, the bewildered young man took stock of himself. This time almost in despair. He was twenty-five, he couldn’t go on living off his parents. He’d do anything to earn his way.

He ran into an old Montana acquaintance who told him that if a man could sit a horse in crowd scenes, there was money to be earned at the film studios. And if he could fall off a horse effectively without killing himself or the horse, the money was even better. There were worse ways to make a living. He forced Chicago and art school out of his mind and went after a movie career.

A career is born

Sam Goldwyn, producing a picture called “The Winning of Barbara Worth,” found, at the last minute, that he was stuck for an actor to play a shy young cowboy, doomed to die. He looked around the lot and found a tall young stunt rider with an appealing, not-exactly-handsome face, and an interesting rolling walk. He offered Frank (now known as Gary) Cooper the role. Nervously, Gary accepted. In clear focus on the screen for once, he lay down to die.

And a career was born.

Paramount saw him and signed him for $125 a week. He had “arrived.”

Now when he went to the studio in the morning, guards nodded pleasantly, executives smiled. He was given sophisticated roles, in which he wore tuxedos, drank cocktails, made love to beautiful women. Clara Bow, the “It” girl, became a close friend and used her influence to get him better parts. He became known as the “It” boy. He wore his tuxedo and drank cocktails off-screen as well as on. He dated beautiful women, too, one of them the tempestuous, glamorous star, Lupe Velez. Their two names made the gossip columns regularly. Gary’s billing got more important. People told him he was on his way.

Yet whenever the pace slackened, he found himself troubled again. On his way to where?

Talking pictures came in with a very audible bang. Gary’s studio hunted for a vehicle on which to try him in this new medium.

They found it in a book called “The Virginian.”

The picture was a Western. Its hero was not sophisticated. He was tall and lean and mostly silent. When he spoke, he chose his words carefully. Insulted in a saloon, he did not shoot the place up or shoot off his mouth. He merely said, “When you say that, smile.”

Today the phrase is trite with overuse. Then, The Virginian was new—someone very different, very special.

To everyone’s surprise, the characterization swept the country like a clean, fresh wind—blowing many good things Gary Cooper’s way. Suddenly he found himself famous, talked about, written about—in a new way. People—strangers, fans, acquaintances—began to revere him, bring problems to him, write him saying that he had influenced their lives. They wrote that it was good to know a man like Gary Cooper really existed. He told himself they were simply confusing him with a part he’d played. But he couldn’t help noticing that off-screen, too, he had changed. He still went to night clubs, wore tuxedos, romanced lovely Lupe. But now it was impossible for him to believe he was enjoying it. The papers speculated openly on when he and Lupe would marry; he knew in his heart they never would. He began to go home earlier from parties, sometimes he didn’t go to them at all. He began to see fewer people and talk to them less. He felt more and more strongly that his stunning career was nothing but a fluke, a fake. He was no actor, never would be. Then he would remember The Virginian. That one portrayal—of that quiet, strong man—had been real and honest. Why?

In search of peace

Between overwork and puzzlement, his health broke down. On impulse he went to Africa with friends who owned a home there. And there, with a gun in his hand, with the dark jungle around him, in the company of men surviving a dangerous life, he found the man he wanted to be—and believed he could become.

What he found was a man who was quiet, strong and gentle; who felt right when he was alone or with someone he loved; who spoke only when he had something to say; who slept best after a hard day’s work; who knew fear and overcame it.

He learned why he had given a true and real performance in “The Virginian.”

It was because inside himself, in every way that counted, he was The Virginian.

And having once learned that, having found himself after so many false starts, he vowed that he would never get lost again.

He came home to Hollywood full of determination. He met a woman who offered more than attraction and excitement—a steady love and a life to be built together. This time he did not hesitate. He and Rocky Balfe were married, and they bought a ranch on which to live.

He intended only to build a way of life that would be true to himself and those who loved him.

But out of it sprang—inevitably—the legend. For in his determination not to violate his integrity, Gary Cooper did things few other Hollywood stars had done. When work made the San Fernando Valley ranch impractical, he sold it, built an unpretentious home, and later one even less showy. There was no longer room in his life for what looked smart but didn’t function.

When his daughter Maria was born, he refused to have her left with nurses and servants when he was called away from home. Families belong together, he said. Unglamorous or inconvenient, wherever he went, his family accompanied him.

He gave up night life entirely. When he worked, he worked hard. When he was free, he took his wife East to Long Island for visits with her folks, or went to Idaho for the hunting season with Ernest Hemingway, another strong and quiet man. When there were only days off instead of weeks, he and his “two girls”—he always called Rocky and Maria that—went swimming and skin-diving near home.

When publicity people, reporters and columnists did succeed in reaching him, he did something even more extraordinary. He told them the truth. Did he like his current picture? He was just as likely to say “no” as “yes.” Interviews with Gary Cooper were never very long. But they were never dull.

A legend grows

Simultaneously, his on-screen legend grew. He turned down showy roles other actors fought for, he chose instead to play quiet and simple men. Sergeant York, who loathed killing on religious grounds yet served his God and country on the battlefields of World War I. Lou Gehrig, the baseball player who fought against an incurable disease—and lost. The tragic young soldier of “A Farewell to Arms,” forced to choose between his duty and his love. Not one of them a conventional hero. They were instead troubled men trying to find their way through a difficult world. When they succeeded, it was not through luck or a gimmick, but by painfully toiling with their problems until they solved them. When they failed, it was with sorrow and without alibis. When they died, it was with dignity. He won an Oscar for his portrayal of Sergeant York and another for his role in “High Noon.”

They were the men in whom Gary Cooper could believe. They were the men on whom he modeled the man he was making of himself.

His own greatest trial came while he was making a movie called “The Fountainhead.” Patricia Neal, a young New York actress, was his co-star. She, too, was a cut different from most Hollywood stars. She was pale and blonde, with a husky voice and intense eyes—very attractive. For the first time since his marriage, Gary was linked to another woman.

With every bit of the strength he had built up over the years, he fought against what was happening to him. When the picture was finished, he took Rocky on a second honeymoon. When they returned to Hollywood. Pat was still there. It was impossible for them not to meet, for the spark between them not to flare again.

What was said, what was thought, what anguish was suffered during his last meeting with Pat, no one knew or would ever know. But Pat left Hollywood, and Gary took his wife and daughter on a long, quiet trip. When he returned, he was smiling again.

Before then, he had fought the studio, fought luxury, fought every corrupting influence that had come between him and his image of a man. Now he had fought and beaten the most dangerous enemy of all—himself.

Years later, when, under different stresses, he and Rocky separated for several months, he didn’t indulge himself in the sort of fling that many older, long-married Hollywood men have had. He spent his time alone, thinking, working through his troubles—a man accustomed to silence. When he had thought long enough, he went home to his wife and daughter, and took with him a weapon against whatever troubles the future might hold. His wife and daughter were Catholics. He was not. He determined to convert, so that they could worship and believe together and their home be immeasurably strengthened.

Just the truth

Reporters asked about his conversion. Coop told them flatly that he was no saint, nor about to become one. Being a Catholic, he said, would simply help him be a little less of a bum.

And later, when he reported to a hospital for his second operation in two months, he told the truth again. “Minor surgery,” the newspapermen who loved him, reported tactfully to the world.

“Major,” said Gary Cooper. Nothing more. Just the truth.

Now he was ill again. The cancer had spread, tearing through his body.

As the doctors applied their cobalt radiation treatments, all Hollywood prayed and wept.

For Gary Cooper had given Hollywood something that few others could.

He gave it self-respect.

He had centered his life around his work and had made his work a fine and honorable endeavor. He had created a public image of himself—and refused to betray it in private.

“We’re very proud of you. Coop,” Jimmy Stewart had whispered. “All of us are—tremendously proud.”

Proud that you lived among us, worked among us.

Proud that you are our product, our seed grown tall and straight.

Proud that you have made us, as no one else ever did, proud of ourselves.

That is the heart and core of the legend, the answer to the questions Gary Cooper asked. If he never knows that answer himself, if he is unable to give himself enough credit, it does not matter much.

The pride is there.

The legend is alive.

They can never die.

THE END

—BY CHARLOTTE DINTER

You can see Gary in United Artists’ “The Naked Edge,” his last picture.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1961