10 Ways Jack Kennedy Is Romantic To Jackie

Jacqueline Bouvier knew from the moment she met Jack Kennedy that her life would be different. It was in 1951, at a dinner party at the home of Charles Bartlett, who was Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times and an old friend. Jackie was just back from a year of studying art at the Sorbonne in Paris and had just finished more studies at George Washington University. As Mr. Bartlett had noticed, she was no longer the round little girl who used to live next door. She was more exotic now, and she had become gayer and livelier. Jack Kennedy, the young Congressman from Massachusetts was handsome, rich and extremely eligible. “It was more than just meeting someone,” she admitted later. “It started the wheels turning.”

She knew immediately that this man would be a disturbing influence in her life and she felt, too, a moment of fear. With a flash of intuition, she thought she saw heartbreak ahead. Then she looked again at Jack Kennedy. As someone else described him at that time: “Kennedy appears to be a walking fountain of youth. He is six feet tall, lean, of hard physique and has the innocently respectful face of an altar boy at High Mass. He is ‘Nature Boy’ with an Ivy League polish, but his exterior nonchalance conceals a terrific will to win.” Jackie looked again and she felt that if there were heartbreak ahead, the pain would be worth it.

What she had sensed in that quick moment was that here was a man who didn’t want to marry. And she was right; he confessed it to her later. But that was later. That warm June night, they parted on the brick sidewalk outside the Bartlett house and they didn’t see each other again for seven months.

Even after that, it wasn’t the usual courtship. For one thing, there wasn’t time. Jackie was busily working for the Washington Times-Herald as an inquiring photographer. Her salary: $42.50 a week. Jack was running for the Senate against Henry Cabot Lodge and was spending most of his time campaigning in Massachusetts. “He’d call me from some oyster bar up there,” she says, “with a great clinking of coins, to ask me out to the movies the following Wednesday in Washington.” But in that clink of dimes and quarters in the telephone slot, there was a marvelous, breathless urgency. He was busy, he was doing great things, with a promise of even greater things. And in the midst of this excitement, he had remembered her.

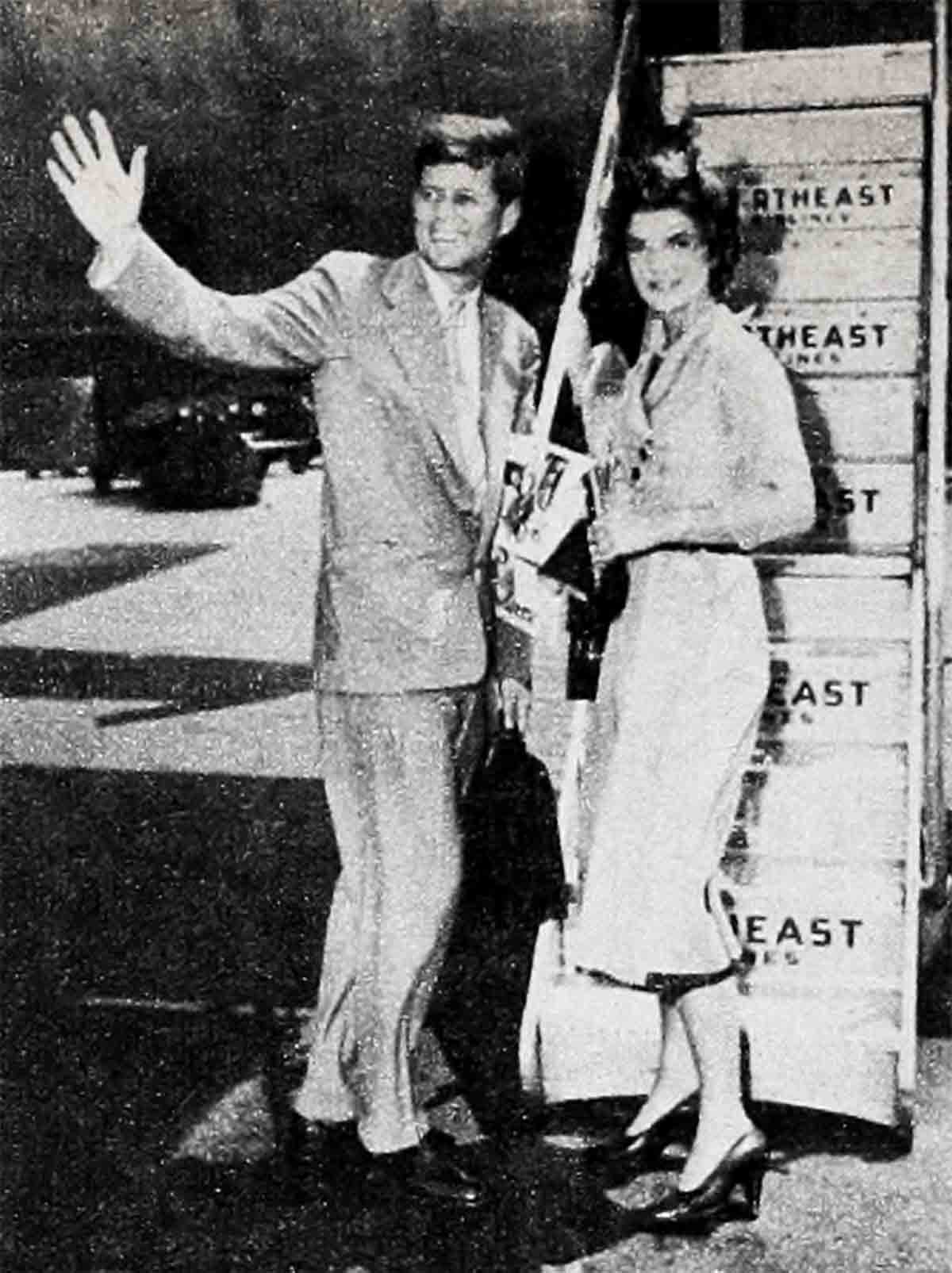

Jack won his race. Who would have doubted it? Certainly not the girl at the other end of those phone calls. He returned to Washington in triumph, more eligible than ever. And now there was more time. For the next six months, Jack Kennedy courted her with the same energy and ardor that had won him that other campaign. The courtship whirled them in and out of Georgetown dinner parties, Washington art theaters and movie houses, south to Palm Beach and north to Cape Cod. In June of 1953 Jack won his campaign. The engagement was announced.

It was then that Jack confessed that she had been right to be afraid. He told her that he had indeed been a man who didn’t want to get married. But that same night, when he met her, he had decided that he would marry her. He hadn’t wanted marriage for a while; he had wanted to wait. But when he was ready, he had decided she would be the one. When he told her, she retorted: “How big of you.”

Three months later they were married—on September 12, 1953—at St. Mary’s Church in Newport, Rhodelsland. And that was the beginning. On a bright, sparkling autumn day, Jackie stood at the back of the church and heard the music start. She heard, too, the rustling of seven hundred guests as they turned for their first look at the bride. She was wearing a taffeta faille gown with a portrait neckline and a bouffant skirt. It was a creamy white to go with the lace veil, now faintly-yellowed, that had been her grandmother’s. Her something borrowed was a lace handkerchief from her mother; the something blue was a garter; the something new, a diamond bracelet from Jack. She started down the aisle to meet Jack and his best man, his brother Bobby. Some of the guests noticed that she clung rather tightly to the arm of her stepfather. Hugh Auchincloss.

“This marriage will take a lot of working out,” she had said. Perhaps, at that moment, she was remembering this.

She had much to learn

She thought she knew Jack Kennedy. But like so many brides, she found she had much to learn about the man she’d married. He was not romantic in the usual sense. When he was courting her, along with the candy and flowers, he had brought her books on politics and American history—and it was obvious these were the important gifts.

She remembered that her mother had once told her to judge a man by his correspondence. At her wedding, she told her guests about this. Then, with a mischievous look at Jack, she held up a card postmarked Bermuda. On one side was a scarlet hibiscus blossom; on the other were scrawled the words: “Wish you were here. Cheers, Jack.” Jackie said. “This is my entire correspondence from Jack.”

But if there was no packet of love letters to tie up with ribbon and sachet, there was something else.

A year before her wedding, Jackie had spent a weekend in Acapulco with her parents. She saw a house there, a charming pink house built on levels against a rosy-tan cliff right over the blue sea. It was a perfect house for a honeymoon and Jackie thought that’s where she would like to spend hers.

And on her wedding day, after she had tossed the bridal bouquet to the waiting girls and then changed into a gray suit, it was to that pink house by the sea that Jack Kennedy brought her.

In the clinking of coins in the phone slot, when he used to call her from Massachusetts, Jackie had heard the promise of excitement. Now that promise began to come true. Jack’s life was a hectic one and Jackie, finding her place in it, decided that she enjoyed it. They were always going someplace—to make a speech, to a political rally, to Europe. Between trips, they lived in rented houses or in houses that belonged to their parents.

“You don’t really long for a home of your own,” Jackie said, “unless you have children.”

They were happy. But there were rough spots, too.

There was the dinner Jackie had planned so carefully. As a senator’s wife, she had drawn up a list of rules, even for informal dinners: “Good food and attractive surroundings. Guests who are interested in what another has to say. A round table so conversation can be general. Lighting not too bright. A feeling of spontaneity.”

Jack walked out

But that night, what happened was too spontaneous. The conversation was dominated by Jackie’s interests—“things of the spirit,” Jack said. “art, literature and the like.” Jack grew restless. He would have preferred a political argument, a heated one if possible. And finally, in the middle of the conversation, Jack pushed his chair back, stood up from the table and walked out.

To Jackie, it must have come as a shock. “I can’t picture disagreeing,” she said. “He always seems so right.” So. together, they began to make the little adjustments that come in every marriage. Jack liked politics and American history; Jackie liked art. Jack preferred steaks and roasts with potatoes or noodles; Jackie liked French food. Jack felt comfortable in open shirts and a sports jacket; Jackie loved dressing up. Jack enjoyed sailing, golf, water-skiing and touch football; Jackie was more the indoor type. Eventually, they learned to live and like, as well as love.

“I learned about American history with Jack’s help,” she said, “and he became a fastidious dresser with a little of my encouragement.”

Yet these were only the small things. There were big adjustments to make, too. The strong bond between them helped.

“We both have inquiring minds,” she said. “That’s the reason we chose each other. I have always felt so alive with him.”

It helped, too. to know that: “Jack would do anything I asked him to.”

Jackie felt that her own family was “very close,” even though, through divorces and remarriages, she had a full sister, a stepsister, a half-sister, two step-brothers and a half-brother. “The fact that we cling together is a tribute to my mother,” she said.

But even her own family ties could not have prepared her for the togetherness of the Kennedys. They were wonderful—or in their family word for anyone wonderful, they were “fantastic”—and they were warmly welcoming. She loved them all individually, adored her father-in-law. And Bobby, she said, was “the most fantastic Kennedy next after Jack. He is the one I would put my hand in the fire for.” She has taught Caroline pride in her name and heritage, sometimes even sternly. When the child weeps over a small hurt, Jackie tells her, “Kennedys don’t cry.” And it was Jackie herself who urged that they move into the “Kennedy Compound” at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, for summer vacations, so Caroline could grow up close to her cousins.

But in time she admitted that Kennedys en masse were overwhelmingly too much of a good thing. She and Jack would take the little walk to his folks’ place evening after evening. The huge dining table would be spread with its impeccable cloth and set with treasured silver—while around it sat never less and usually more than a dozen hotly arguing Kennedys. Not personal arguments—just opinionated battles over politics, sports or whatever excited them. Jackie rebelled, finally. “Once a week is great,” she said. “Not every night.” And after breaking her ankle at their favorite game, touch football, she stayed out of those family scrimmages, too.

The “spite fence”

During Jack’s campaign for the presidency, Jackie put up a fence around their vacation home to keep out the hordes of reporters, photographers and curious people. But gossips called it a “spite fence” and said it was put up to keep out Kennedys, too.

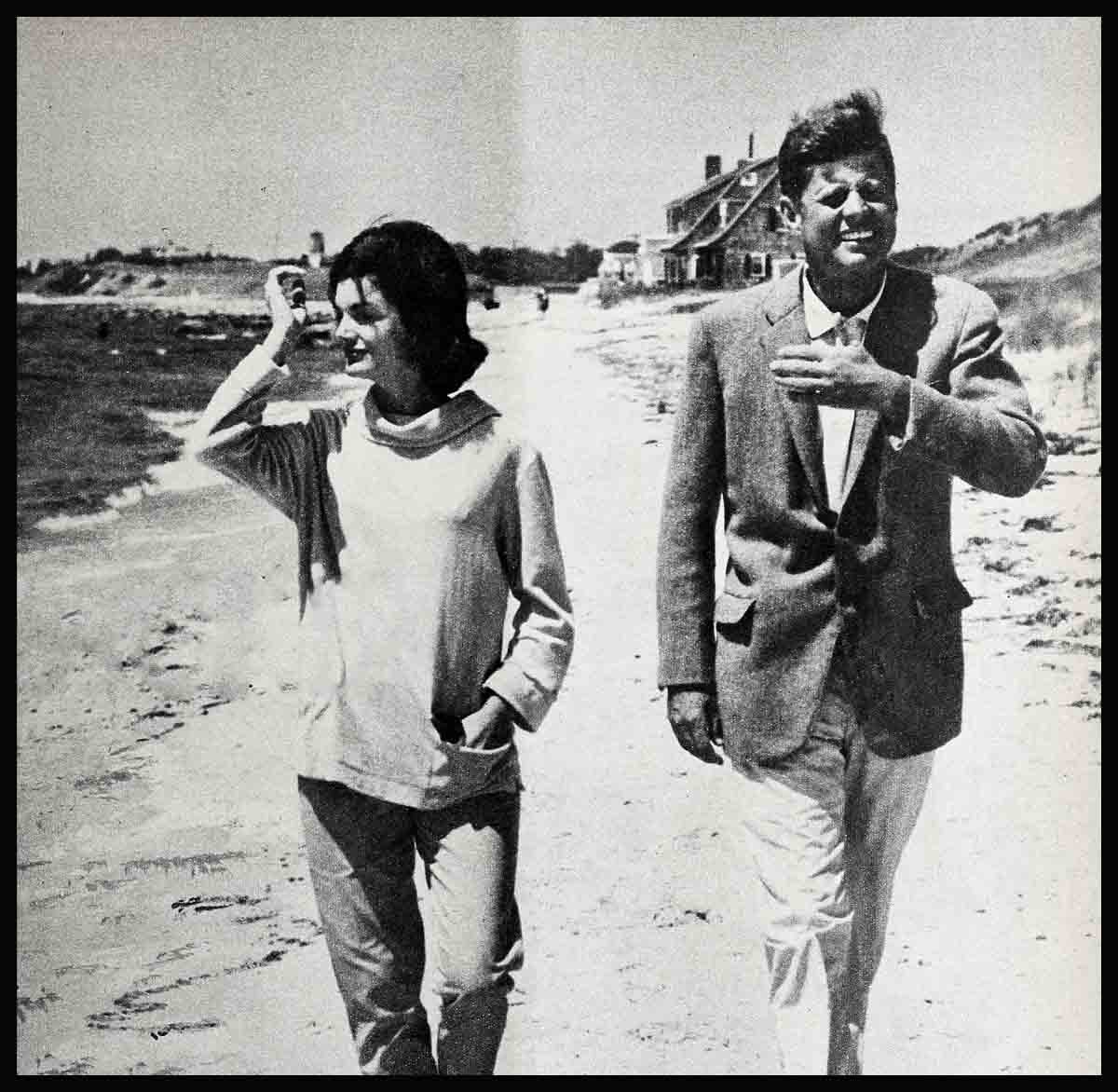

Yet Jackie found that the Kennedys think all the better of her when she stands on her own rights. On Jack’s sailboat, the Ventura, they would often cruise all together along the Massachusetts coast, lazily content in the hot sun blazing down on the water. But come lunchtime and the in-laws would picnic on peanut butter sandwiches and Cokes, sprawling in the bow, while in the stern Jackie passed unusual French delicacies to her husband and guests. And nobody thought anything of it. “They seem proud of the things I do differently,” she said. “The very things you think would alienate them bring you closer to them.”

Her marriage was a pendulum swing from extreme to extreme—from the clan’s too-togetherness to too much aloneness from the one she wanted most to be with. When she married Jack, she thought she knew what she was getting into. But the separations were worse than she’d dreamed. And for the first four years, while he raced all over the country, she was alone whenever she could not go with him. She had no child to occupy her time and heart. When Jack was away she kept busy enough with her books and painting, so that she was at least content—but never happy without him.

Perhaps the closest time in their early marriage was the frightening eight months during which his old back injury nearly cost him his life. He’d been hurt playing wild college football—to keep up with his adored older brother Joe, who was killed in the war. Jack’s own heroic rescue of his PT-boat crew during the war made the old injury even worse. During chronic bouts of terrible pain he must have been haunted by the thought that he could end up crippled like his sister Rosemary, a spinal meningitis victim who now lives in a Wisconsin nursing home. Finally, in 1954, he decided to risk a dangerous spinal operation. Jackie watched as they wheeled her husband away on a stretcher to the operating room. She waited, pale and anxious, until the doctor finally emerged. He told her the operation had failed. And Jack was so near death that the rest of the family was called to his bedside. With stricken eyes, she watched as a priest came, too, to administer the last rites to her husband. But Jack doggedly pulled through, for a second operation that did work.

During the long convalescence, his bride of a year lived for one thing—to cheer him. Reading to him, running contests to see who could memorize the most poetry—that was the least of it. She poked in old bookstores for odd books to rouse his interest, she found crazy presents to make him laugh. And one particularly grumpy evening she stayed outside the room door while she sent in a visitor who announced, “I’m your new night nurse.” It was Grace Kelly!

In Palm Beach, still bed-ridden, Jack used his time writing what turned out to be a best seller and Pulitzer prize winner, “Profiles in Courage.” But without Jackie it couldn’t have happened. She helped with the research. She sat long hours by his bed with a pad of ruled yellow paper, taking notes, or writing down whole chapters in longhand. The preface pays tribute to “my wife Jacqueline whose help . . . I cannot ever adequately acknowledge.”

She did more than that for him—she taught him to paint. She gave him her materials and brushes and he sloshed away in bed. He had turned out some promising pictures before his mother finally balked at the splattered bedclothes. She made him hold off until he could sit on a chair in the bathroom—it was more washable!

Husband and wife both learned from the pain and companionship of those eight months. Jackie came out of it more of a woman—more tender, more understanding. She said of him, “He was so brave—always.” And he came to understand her ups and downs—they’ve remained part of her charm for him. They can always make each other laugh, and he can never “get mad” with her. The man who was too busy before marriage to think about a woman’s mind or emotions now admired both in his wife. It helped, in the next few troubled years. For in 1955, the girl who so longed to have children suffered a miscarriage. And in 1956 he lost—by a hair—the nomination for Vice President. He took his defeat alone in Los Angeles where the convention was held, and she took it by the radio at home, because she was again expecting a child. But, a month prematurely, the baby was born by emergency Caesarean section—dead.

That third year of their marriage was the bitterest, and Jackie almost did not survive it. There were people who thought the marriage itself wouldn’t survive, but it did. Some time before their third wedding anniversary, the young Kennedys sat down together and frankly talked out their marriage problems. Out of the searching reappraisal came a new growth in accepting each other’s personal preferences, tastes and ways. Also, judging from Jackie’s remarks later, they had arrived at a deeper understanding of the husband-and-wife role.

When Caroline was born, the day after Thanksgiving. 1957, Jackie’s happiness was so great that she used to fight off falling asleep. She would lie in bed willing herself to stay awake so she could savor every last blissful moment of each day with a husband and baby to love.

A home of their own

To add bliss, when Caroline was three weeks old, they moved at last into a home of their own—a red brick Federal style dreamhouse in Georgetown, outside of Washington, D. C. More often than not, the man of the house was away, covering the country on speaking tours. And even when he was home, Jackie said, “Weekends when most people are relaxing, Jack works hardest.” But when he could, he enjoyed the soothing drawing room with its chairs comfortably upholstered in palest green . . . the offbeat touch of pink-gilt cups and saucers used as cigarette containers and ash trays . . . Caroline’s gold-belled coral baby rattle for an ornament. The house was full of pictures and books and flowers. And regularly, out of the kitchen, went Jack’s daily lunch to his Capitol office—nourishing meat and vegetable and potato meals that his wife believed in for a growing senator who used up a lot of energy. A hot plate, just like baby Caroline’s, kept the food warm on the trip over. Jack was so intrigued, he stopped snatching a sandwich or candy bar for lunch. Soon he was asking for three or four or more hot plates, for guests who admired Jackie’s “catering.”

After the bliss of finally achieving motherhood, the new pregnancy, in 1960, was super-bliss. But once again she was torn two ways. She was doing everything a wife possibly could to help her husband win the biggest campaign of them all. Yet all the while she was deathly afraid of what this over-exertion could do to the baby expected at Christmas. It would be her third Caesarean. After the election, only those close to her knew the fear in which she rode beside him in the victory parade. It was the peak moment of his career—maybe even of his life!—and her strength was nearly spent. A few weeks later John Kennedy Jr. came into the world prematurely. Only a matter of minutes—and luck and a good doctor—saved him.

These are the hazards of life that the young couple pulled through. How did they come out of it—the young wife who was once considered to have more intellect than tenderness, and the husband to have more power-drive than insight into her needs? Jackie’s own words reveal the change. When they were engaged, she said. “I think Jack is up to anything . . . he gives others confidence . . . with him I think I could do anything.” Now she sounds like millions of happy wives: “I’m an old-fashioned wife . . . keeping a house is a joy to me. One of my greatest pleasures is to see that everyone else is happy in it.”

They need each other

Much of the happiness lies in needing each other. His job may have to come first, like so many men’s. And she keeps up a busy outer and inner life of children, home, books, painting. But everyone close to them says they would be lost without each other. When she walks out of a room, his eyes follow her. If she is gone too long lie asks restlessly, “Where’s Jackie?” . . . And of her need for him, and the children’s need, she says, “Even if he is President, we must have some time with him.”

But, of course, even though Jack now understands her need, there is still no such thing as enough time for them together. A big part of her life must still be lived on her own.

Nevertheless, Jackie can now say of marriage, “It’s easier for the wife to make the husband happy. His career is half his life, so if the wife does the minimal things, he will be content. But if the wife is happy, full credit should be given to the husband.”

Jackie is happy. And one reason is this: that busy as her husband is, he notices her—notices everything about her. The night of the inaugural hall she put on the gown that an entire nation would be eager to see on TV. Every detail of her costume had been carefully planned, designed to be perfect for the occasion—exquisite yet simple. But at the last minute he felt that she would be even more beautiful wearing a necklace with this gown.

She put on the necklace.

He had paid her the compliment of really seeing her, and she had returned the compliment of accepting his taste and his decision.

Books, records, a necklace, a diamond bracelet, a call from a pay-booth station, a battered old postcard, a tie when she knows he’d prefer to go tieless, a walk when he’d rather read, a hook dedicated to her—but probably the greatest gift Jack has given Jackie lies in this, which she so candidly admitted: “Happiness is not where you think you find it. I’m determined not to worry. So many people poison every day worrying about the next. I’ve learned a lot from Jack.”

THE END

—BY JULIA CORBIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1961