The Ladds, Inc.

The studio had found them rooms at the Sherry-Netherlands, and they went there directly from the station. After the air-conditioned Chief and Century, the sick-damp, enveloping heat of New York seemed inexcusable and insufferable, like a deliberate insult. By the time they reached their suite, they felt as if they were walking in a steam bath, and their hair and clothes looked it.

Standing before her mirror, trying to peel a blouse off over her head, Sue mumbled through the folds of silk, “I was going to say it felt swell to be in town again, but I’ve changed my mind.”

Alan was already in the shower, she realized, when she at last emerged from the blouse and heard the water running. She snorted. “Beast! Where are your manners?”

He stuck his head out of the curtain. “Something?”

“I give you just thirty seconds to get out of there.”

He was out in twenty-five, and after she’d had her shower and dressed, they sprawled in opposite chairs and grinned at each other. “I may live,” Alan said.

“I’m all over my temper, too. But do you realize I brought nothing but fall clothes with me? I thought surely with October so near—The effects of this shower are going to last about ten minutes.”

“Let’s try to be like children and not pay any attention to the weather.”

“Children metabolize at a different rate, honey, and anyway they’re not expected to look crisp in hot weather. What’re we doing tonight?”

“Harvest Moon Ball. Madison Square Garden.”

“Well, let’s have dinner on a roof somewhere, anyway. I want some lobster Mayonnaise, lobster with real claws, and some breeze, if there is a breeze.”

There wasn’t any, even on the terrace of the Starlit Roof. Sue pointed wryly at the sleeves of her dress, already wrinkled on the inside at the elbow. Alan mopped his forehead and drank his chilled Vichy-soisse. “Think I’ll find an air-conditioned movie and pitch a tent in it,” he said.

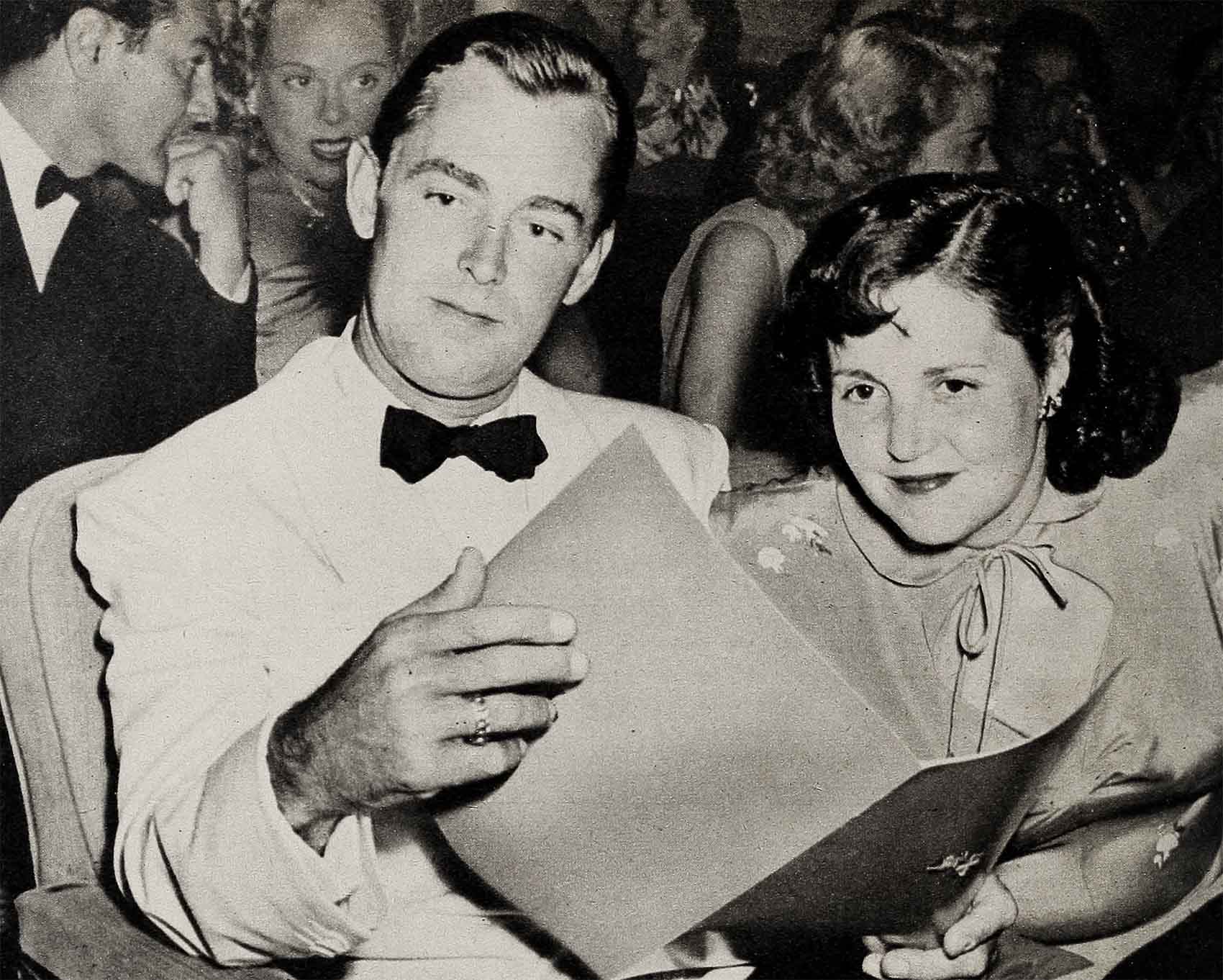

But they appeared at Madison Square Garden on time. And then it happened. The spotlight caught Alan, singling him out in the vast amphitheater like a bug on the end of a golden stick. An amplified voice announced who he was. After an instant’s silence, bedlam broke loose.

They would not stop, for minutes. Finally, Ed Sullivan managed to make his voice heard long enough to announce that this was Alan’s birthday. Then twenty thousand people stood up and sang “Happy Birthday To You.” As she listened to the silly little song roared out in such majestic volume, Sue discovered, to her surprise, that she was crying and thinking, like any wife of any important or popular man, This is it. It’s wonderful moments dike this that make it all worth while.

And when Alan finally spoke into the mike, his normally deep voice was high-pitched and hesitant, too, with emotion.

In the early morning hours, before going to bed, they strolled along empty sidewalks for a time and stopped for a cup of coffee in an all-night beanery. They did not have much to say, but even in the continuing heat, each recognized in the other a mood of calm happiness.

They did not work too hard at it, this trip. They stayed as often as they could with friends on Long Island’s North Shore. In town, they saw Brigadoon and Finian’s Rainbow and Annie Get Your Gun.

There was business to attend to, and Alan attended to it with a grim determination. He had originally wanted to make records, as he has an excellent Singing voice, but Paramount felt that popular ballads were not in harmony with the kind of character Alan portrayed on the screen. In all justice to this point of view, it is a trifle hard to envision the Man With the Gun crooning tender sentiments about moon and June via the corner juke-box. In any case, Alan had surrendered that ambition, not without battle, and had turned to another idea.

This was a radio show called “Box 13,” in which he would play a young writer who advertised for adventure—and found it. Paramount had at first said no to this, too, because radio rehearsals would take him away from his studio work; but they had agreed to transcriptions.

So a corporation had been formed, and the first waxings made. The show was being sold across the country, to local sponsors, and Alan was still in the midst of negotiations when he was called to West Point for a week of shooting. It was there that he almost ended up in the guard house. One afternoon, when the last sweltering take had been finished, he unbuttoned his tunic, shoved his cap on the back of his head, put his hands in his pockets, lit a cigarette, and started wearily across the yard. An officer of the day took one look at him, shuddered, and went sprinting in pursuit.

Alan turned in surprise. “What’s the matter, Mac?” he asked.

It was another long minute before recognition came.

The location trip had been fun, but they had come back to Hollywood on September 20th, and further shooting on The Long Gray Line would not begin until October 13th, wherefore it was obvious that Alan would have to get himself interested in some new enterprise.

Learning to make Early American furniture as a pupil to George Montgomery was obviously the answer.

the home-made home . . .

This idea presented itself one afternoon. Sue and Alan in the just-finished living room of the Montgomerys’ house, were sitting staring with awe—not at Dinah, radiant as she was with the happiness of coming motherhood, nor at George—but at the furniture.

“That table,” Sue said. “It’s none of my business, but where did you dig up the buried treasure? I’ve been trying to find a few Early American pieces for the new room at the ranch, just one room, and the budget’s cracked at the seams already.”

“Ha!” Dinah said, on a note of triumph. She stood up. “Follow me,” she commanded, and led the way out the front door, across the lawn and motor court, past the garage to a doorway. She opened the door and stood aside. Past her came the clean sharp. smell of lumber, turpentine and shellac, varnish and wax.

They went inside. Standing everywhere were nearly finished pieces of furniture, scattered among the permanently anchored, gray-painted electric saws, drill-presses, lathes and vises. It was a complete, modern shop.

“It beats me,” Alan said finally. “You can’t find the furniture you: want, so you create a manufacturing plant in your back yard, hire a raft of cabinet makers, and have a custom job done. But wait a minute, what about that patina, those wormholes, that authentic use of porcelain?”

“Who said anything about hiring anyone?” Dinah asked indignantly. “I’ll have you know that George made every one of those pieces by himself!”

They watched as George neatly turned a delicate chair leg on a lathe, fitted it to a chair, pegged and glued it, made with sandpaper and pumice stone, and generally behaved like an accomplished cabinet-maker.

Driving back to the ranch late that night, Alan said, “Darn it, I’ve never felt so inferior in my life. All that furniture’s as good as any I’ve seen in the best shops.”

“Don’t be silly,” Sue told him loyally. Why, you helped the carpenter all the time when he was building the new room, and put most of the shingles on the roof.”

“It isn’t the same. Anybody can pound on shingles.”

Sue was tired when they reached the ranch, and paid no attention to the number of mysterious articles Alan kept fetching from the car. She went immediately to bed. About one o’clock she woke up, aware of odd grinding and scratching noises coming from the new room.

Mice? Sue thought. Already? (She knew the older part of the house was swarming with them, but although the Ladds possessed seven cats, none was housebroken enough to be allowed inside, and thus the wildlife abounded, unrestrained; the beasties ate very little, in any case, and always ran and hid when they saw her, so she didn’t really mind.)

Then she saw a rim of light under the door, and realized that Alan had not come to bed. She put on a dressing gown, and went to the new room.

Alan, kneeling beside the new woodwork of a built-in cupboard, looked up as she came in. He was holding a peculiar, awl-like tool, and on the floor beside him were a saw, a large amount of scrapings, and bits of woodwork.

“What on earth are you doing?” Sue asked. Then she looked closely at the cupboard. She closed her eyes. “Do you know what that cupboard cost?”

Alan regarded her without offense. “I’m antiquing the thing,” emnly. “George showed me how. I borrowed some of his special tools. Watch.” While Sue gritted her teeth, he punched half a dozen more wormholes into. the fresh wood with the instrument in his hand, then took the saw and rasped its sharp teeth across the panels.

“How do you like it?” he asked.

“I think the only word is ‘extraordinary’.”

“Want to help?”

“You mean you’re going to do—this—to more of the woodwork?”

“Well, I’ve gone this far. I mean, it would look kind of silly, wouldn’t it, having an antique cupboard and everything else all fresh and unspoiled?”

“I like that last word,” Sue said. Suddenly the spirit of the thing caught her. “By no means,” she said, “should we do this thing by halves. You take the saw. I’ll take the punch thing. Ready?”

“Ready.”

So the sawdust flew, far into the night.

furniture fever . . .

After that, there was no holding the Ladds. There had to be two cabinets made, first, to flank the entrance to the new room. One would hold the radio-phonograph combination, the other Alan’s records and anything else that needed holding. They must be Early American, thoroughly antiqued, and as good as anything George could turn out. Alan knew George wouldn’t mind sharing his shop.

He and Sue arrived at the Montgomerys’ just at lunch time one day, refused luncheon, having just finished; and made at once for the workshop.

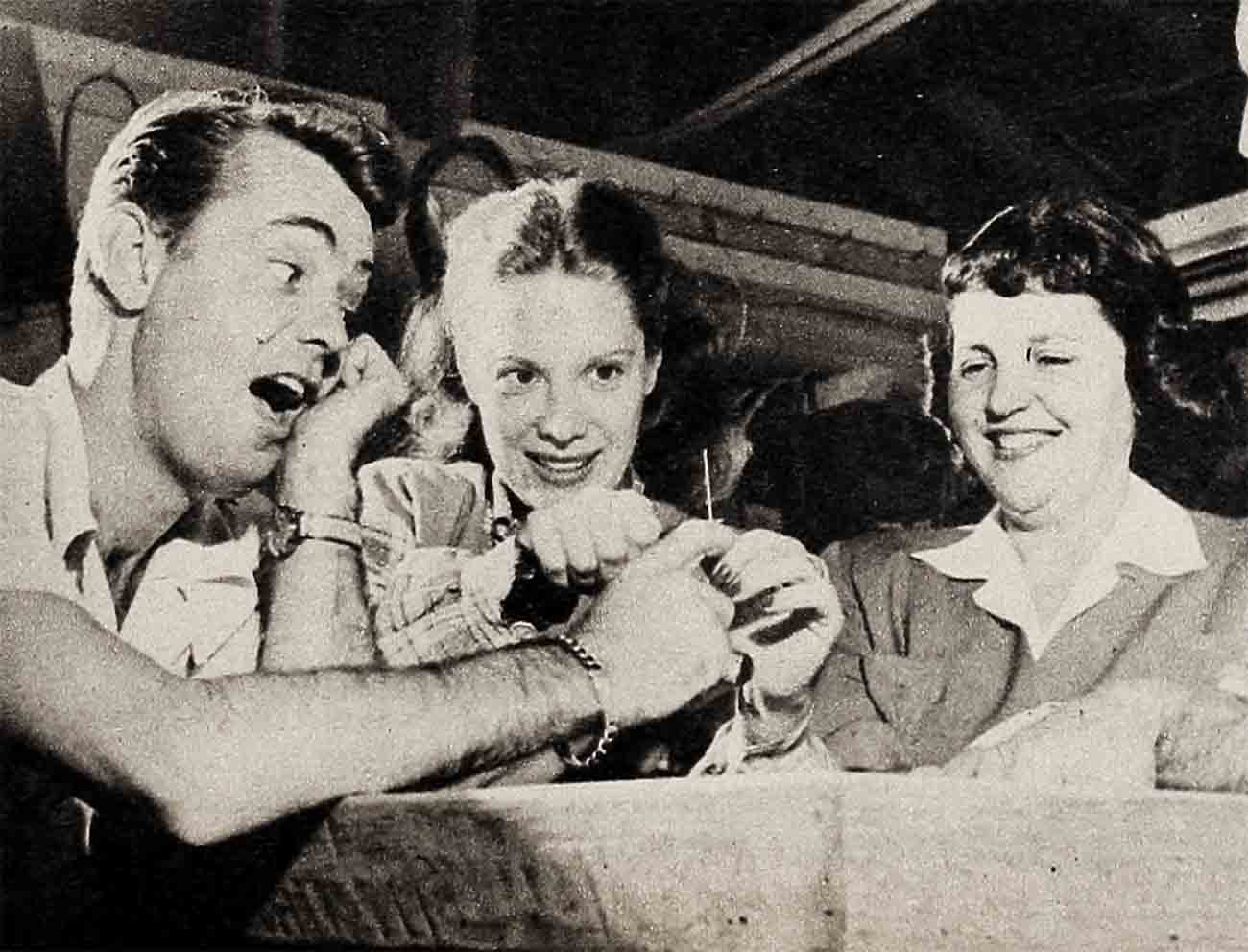

Half an hour later George and Dinah came out to watch. The cabinets were all but finished. The knobs had to be screwed on, a few more worm holes added; and the first application of high-smelling goo that eventually would create the color and shading of an old, treasured piece, made a century or two ago.

There were a few slip-ups. Alan had the entire side of one cabinet brushed in before George discovered he was using the wrong mixture.

He also got a sliver the size of a golf club caught deep in his finger; the thing apparently had a barb on the end, and it took the combined efforts of everyone present to dig it loose with a jack-knife.

It was several days later that Alan and Sue, driving the convertible, followed the truck on the San Fernando Road. The truck was carrying the last load of furniture, and it was almost five o’clock.

Deadline was near. An empty room awaited them, but the material to bring it alive was here. If they didn’t pull it off tonight, it would be another week or two before Alan would have time. Shooting on The Long Gray Lineresumed the next morning.

The days were getting shorter, now, and as the truck ahead of them pulled off the highway on the side road that led to the ranch, it was almost dusk; the dark earth against the still light sky created a deceptive area of shadows.

It was perhaps because of this that the driver of the truck switched his lights on, then off again, headed directly for a tree, sheared away from it just in time and hit a deep rut in the road that bounced the rear wheels two feet off the ground.

“Hey!” Alan said, under his breath. Helpless, he and Sue watched while a double wing chair and a large table very slowly slid back to the roadbed.

The truck and the convertible came to a halt. After a moment Sue stirred in her seat. “Go ahead and say it,” she commanded, “for both of us.”

Alan said it. Then they climbed out of the car and inspected the damage. It was considerable.

“Does the insurance—?” Alan began.

“I don’t know,” Sue said.

“I just didn’t see the bump,” the truck driver explained unhappily.

“That’s okay. You might have hit the tree and hurt yourself. Give me a hand with the table, will you?”

At the ranch, fifteen minutes later, they stood and surveyed the empty room and the stacks of furniture, the crates of books and ornaments, the boxes of curtains, the rolls of rugs. Alan took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves. Sue slipped a smock over her dress. Without a word, except for mumbled “Excuse me’s” and “Where’d you put the tacks?” they had worked without pause until nine o’clock.

Only then, hair mussed, perspiration-streaked, backs aching, they stood together and looked at their handiwork.

They had created a miracle. The room glowed before them. It glowed a little too brightly, because the material for the lamp-shades had turned out to be the wrong color and had been put away for exchanging; and one window had a curious look about it, because Alan had hung the curtains upside down—but the impossible had been accomplished.

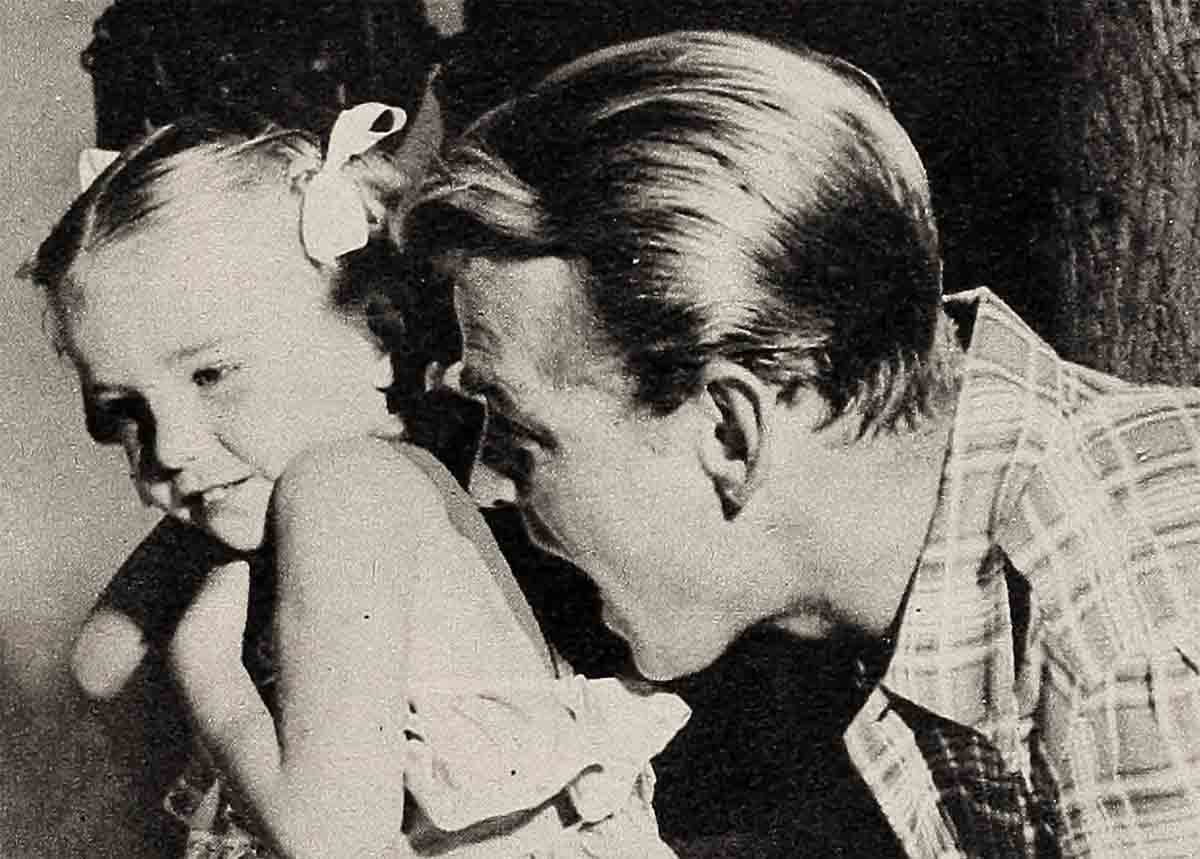

Alan put his arm around Sue’s waist, and bent his head and kissed her lightly.

Five minutes later they were in bed, and sound asleep. And, oh yes, the insurance on the double-wing chair and table was okay.

THE END

—BY HOWARD SHARPE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948