Wedding Bells Toll Elizabeth Taylor & Richard Burton’s Doom

An amiable drunk brushed against our table, grinned foolishly and asked, “You know what it sez on Liz Taylor’s towels?” Nobody answered him. Maybe then he’d go away. We had things to talk about. “It sez, ‘His,’ ‘Hers’ and ‘Next’!” he said triumphantly. Nobody laughed, either. Deflated, he wavered his way back to the bar.

I said to the two men who were my luncheon guests—a lawyer and a psychologist—“You see now what I mean? About Liz and Burton getting married?”

But my friends, though professionally quick on the draw, didn’t yet see what I was driving at. They knew I had invited them to lunch because I was writing a magazine piece on Liz Taylor and wanted to pick their brains a little.

“But I still don’t get the connection,” said Bert, the lawyer, “between an unfunny joke and your topic.” My topic was “Why Wedding Bells Toll Liz and Burton’s Doom.” I answered with another question. “How many Liz-Burton-Eddie jokes have you heard lately?”

Bert laughed. “Oh I get around,” he said. “I heard the one about Liz waking up in Rome one morning and saying, ‘I feel like a new man.’ But frankly, I can’t listen to those jokes any more—maybe I’m the last of the Puritans.’ He added, “Let Phil listen—a psychologist listens to worse.”

Phil quipped back, “Who listens?” Then, “But seriously, there is nothing worse than those Liz jokes. I read the newspapers and I get the impression that inventing cracks about her has become a big major industry. I agree with Bert, the whole thing has become pretty distasteful—even ridiculous! Jokes, gossip, blasts in the Italian papers and American papers and now the Swiss papers . . . news stories, editorials, letters to the editor . . . attacks from churchmen, from government officials . . . women’s clubs threatening to boycott her pictures . . . boos and hisses when Burton’s face is flashed on a screen—or Liz’ name mentioned—it’s too much!”

“Hold on,” I said. “Are you trying to say that those two don’t deserve the attacks? That they’re innocent victims of a conspiracy? Or the whole thing is only a publicity hoax?”

“Don’t put words in my mouth, you writer,” said my, psychologist friend. “Let’s just discuss what all this hoop-la and shouting means to the leading characters themselves.”

“Fine,” I agreed. “What do you think it means?”

“I think that every time a new joke about themselves gets to their ears,” he said, “and every time someone high up blasts at them, Liz and Burton are that much more closely united—in joint self-defense.”

“Yes, and I’ll tell you something else about Liz and self-defense,” the lawyer broke in. “When that Italian newspaper Osservatore Della Domenica accused her of ‘erotic vagrancy,’ what did she do? She snapped back, ‘Can I sue the Vatican?’ ”

“Well now, that’s the response you’d expect from a petulant child,” said the psychologist. “I’d say that the more these two feel rejected and condemned by society, the closer they’ll cling to each other and rebel together.”

I nodded. “I think you’re right. If the world ignored them, they might not keep working themselves up to the Grand Passion of the Ages.”

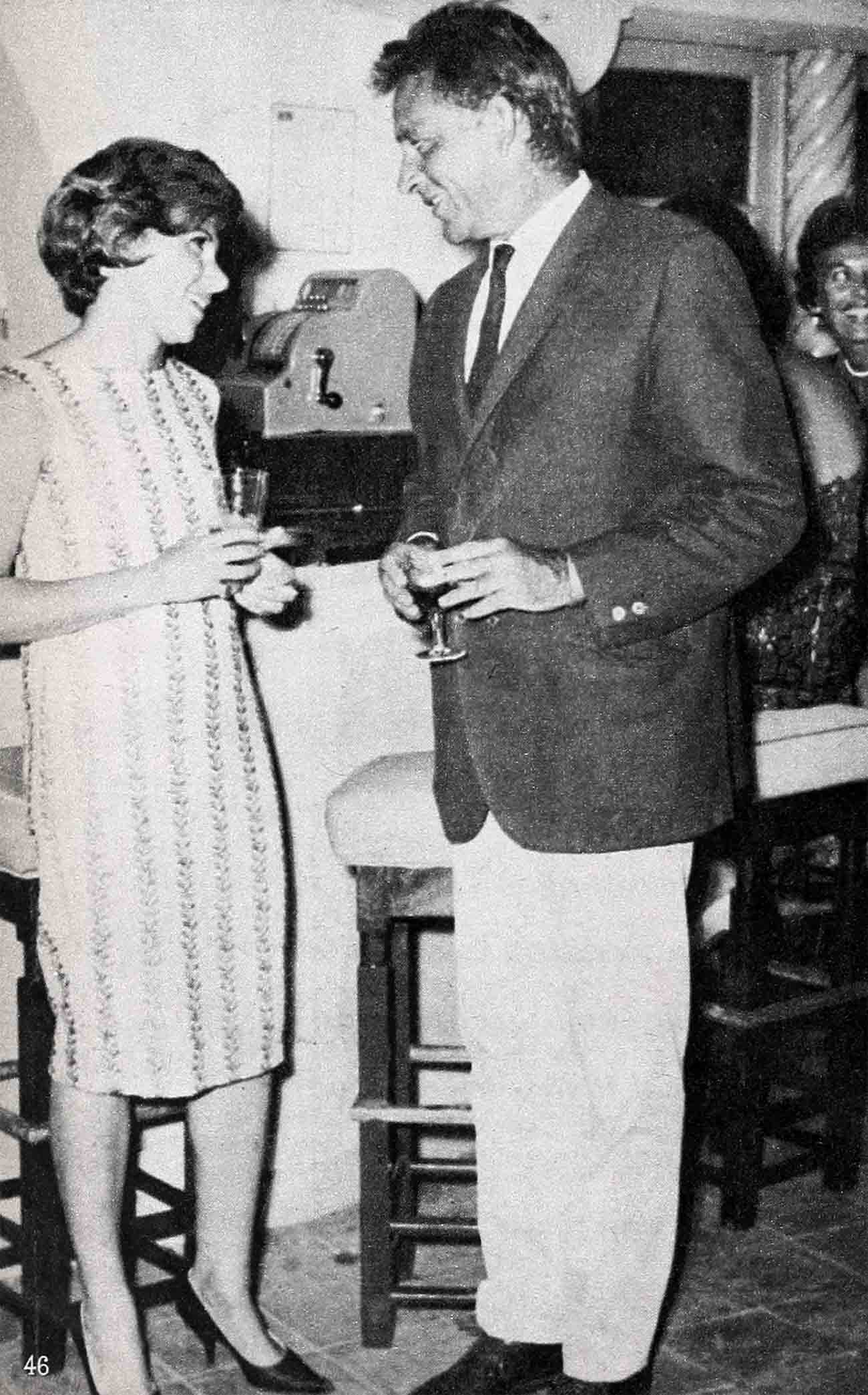

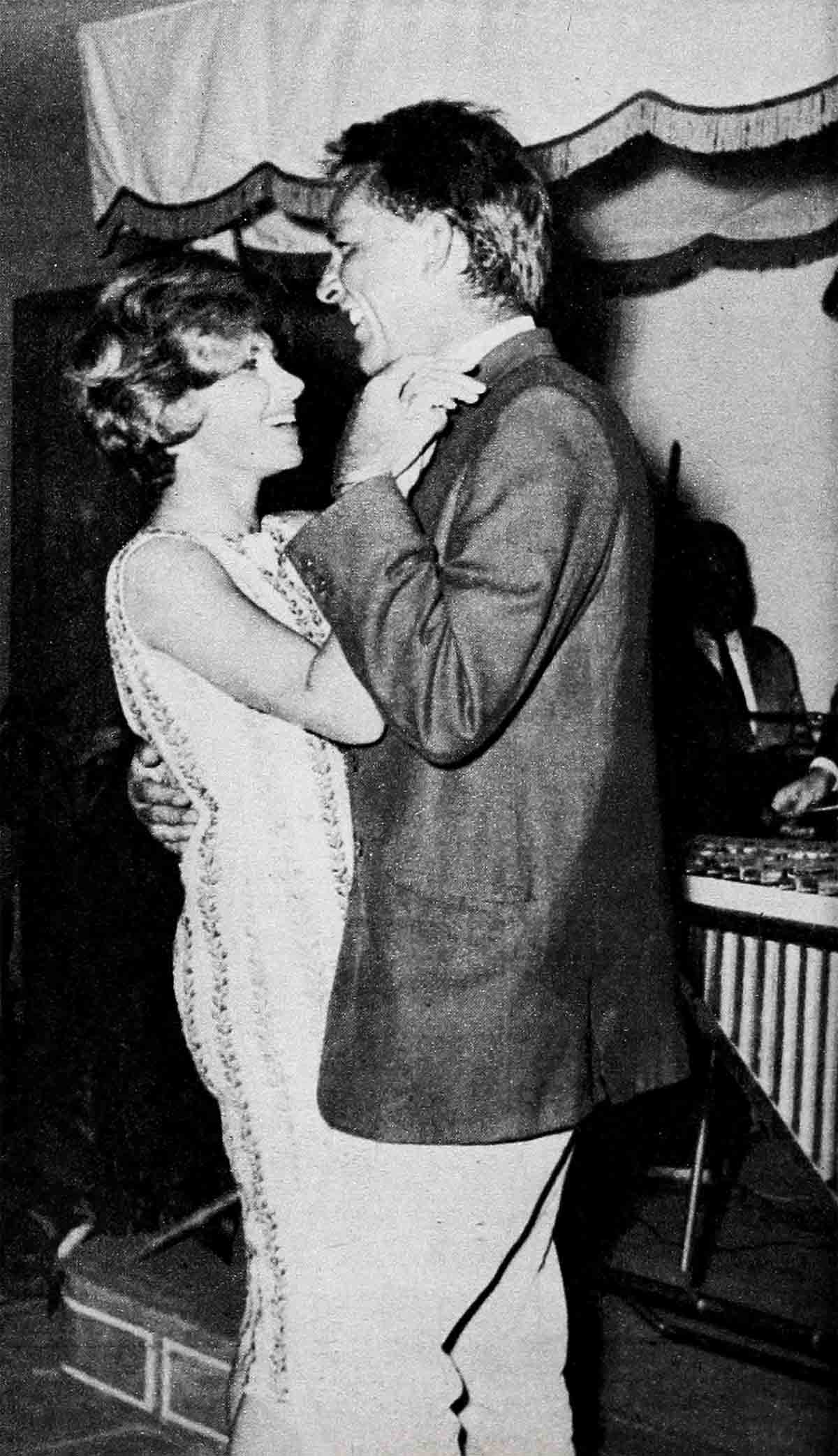

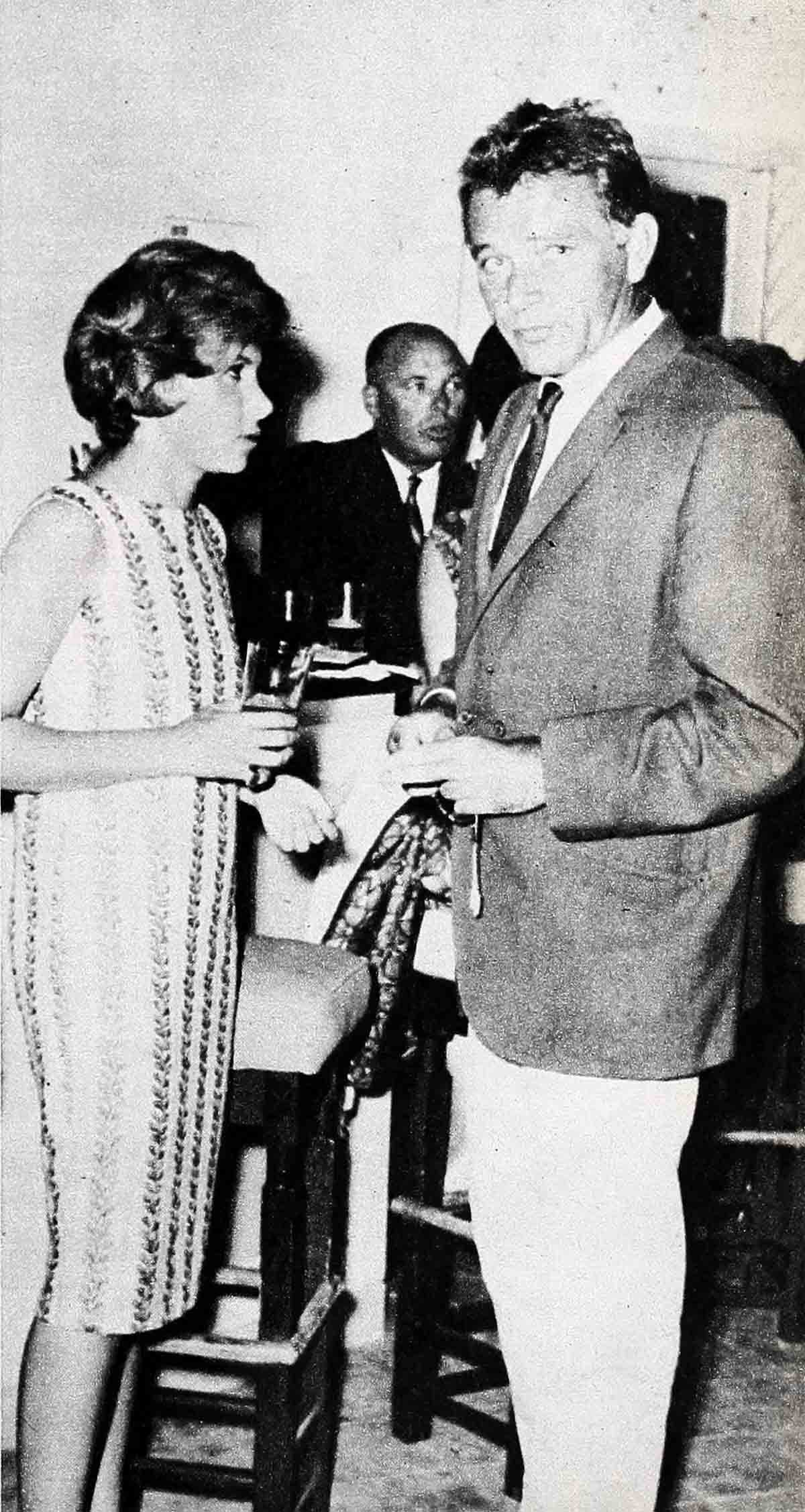

“But how can you ignore something like those pictures on the yacht at Ischia?” demanded the lawyer. “Maybe I sound like a Puritan again, but those pictures would make a strip-teaser blush! Is that rebellion—or is that flagrant, flamboyant disregard for decency?—not only to have an affair but to insist on exhibiting it to the world?”

“What Sheilah Graham said in a column,” I told him, “bears out what you feel—that they are rank exhibitionists.” I fished the clipping out of my briefcase and read from it: “ ‘The antics of La Taylor have gone beyond the bounds of belief . . . Liz does not care what anybody except Burton thinks of her. She obviously believes that she is a law until herself.’ ”

“Exactly,” echoed the lawyer. “A law unto herself.” He felt vindicated and sounded pleased about it.

“Yes, but on the other hand,” I picked up another column I’d clipped, “here’s Dorothy Manners quoting a famous restaurateur who was Liz’ guest at her villa recently. He reports: ‘Don’t believe that all that has happened has not touched her. She is hurt and bitter and suspicious of almost everyone.’ ”

“An interesting dilemma,” said the psychologist. “If both these items are accurate and true, we have a woman who flaunts public opinion because she is so sensitive to it. Like a petulant child determined to show that she’s even naughtier than people say she is.”

“Aha!” I exclaimed, “now you’ve made a point for me—that Liz and Burton must get married because it’s the only way they can break out of this vicious circle they’re caught in. Look . . .” I described the circle. “The press, the public, plagues them . . . so they cut up wilder and wilder to ‘prove’ they don’t care (when actually they care very much) ; so then they’re accused of ‘moral turpitude.’ And this they resent so much, they slap back by indulging in even more shocking acts of public exhibitionism. Then they’re slapped—and the circle gets tighter—till the only way out is to smash out with the biggest scandal of all—the final nose-thumbing. She will have broken up his ‘happy home’ and he will have left his wife and two children. And the world be damned!”

The psychologist leaned across the table to me. “Doesn’t all this sound familiar?” he asked. “Didn’t the whole thing happen to Liz four years ago? Didn’t she and Eddie go off together before they were a great love? Liz liked Eddie, and he wasn’t in love with his wife Debbie any more than Burton seems to be in love with his wife Sybil. But Liz and Eddie went to Grossinger’s that famous Labor Day in 1958. They went for a weekend—not an eternal romance.

“But all hell broke loose, the world jumped on them. Back home in Hollywood, Liz hid in her house but photographers climbed her walls and reporters trampled her lawns. She hired police guards, but curiosity seekers managed to peep into her windows. She became the villainess of villainesses. She didn’t get an Oscar she deserved. The Theater Owners of America cancelled an award they were going to give her. Pickets paraded outside the Las Vegas club where Eddie performed. Old friends didn’t phone Liz—but anonymous voices did—to spew hate at her. She received tons of defamatory mail about which she said, ‘Some of the bad ones made you feel like you had to take a bath, the language was so obscene.’ ”

He stopped for a breath and a sip of water.

“You are very informed,” I said with a smile, and my lawyer friend echoed, “Yes, for a psychologist you certainly know the scuttlebutt.”

“I read like everybody else,” said Phil, “and I remember.” He went on, “I’m convinced it was the opposition, the vilification, that forced Liz and Eddie to fall in love—or think they had. It was the two of them against a hostile world.

Marriage—a mistake!

“And so they were married. And here’s something I read recently: that not long after the wedding, Liz burst into Joe Mankiewicz’s office—he was directing her in ‘Suddenly Last Summer’—and she sobbed hysterically, ‘I’ve made a terrible mistake in marrying Eddie.’

“But even after the honeymoon was over, the blasts came from press, public and pulpit. And that did it. Just as condemnation had pushed them together—into love and into marriage—now it kept them together. If the world had only ignored their earliest escapade, they might have gone their separate ways.”

There was a little silence, as we all digested this thesis.

Finally the lawyer said, “Then I take it that the pattern will repeat itself and we can predict that wedding bells will toll for Miss Taylor and Mr. Burton.”

“That’s not the proposition on which I am writing my piece,” I challenged him. I “I am going on the theory that wedding bells will toll doom for Liz and Burton.” I took more clippings from my briefcase. “Just on the practical side alone, on the comfort level, try to visualize what kind of a wife Liz will make her Dickie. Listen to what Shelley Winters said about Liz: ‘She doesn’t know how to go to the grocery store and, if someone doesn’t bring food to her room, she’d starve to death. All her life people have done things for her and have told her what to do.’

“And here’s how a reporter described Liz’ housekeeping when she was married to Mike Wilding in 1956—and there’s no reason to think she’s improved: ‘Most of the sheets are ripped, and the grass-cloth wallpaper near the seven-foot-six-inch bed she shares with Michael is shredded by cat claws. Their guests, while eating from a glass-and-teakwood table and drinking vintage wines, find themselves using such mismatched utensils as long-handled iced-tea spoons to pry out grapefruit sections.’

“Well,” I went on, “maybe it’s not the end of the world, what kind of silver you use—but if Burton hooks up permanently with Liz, he’s going to miss the order and comfort Sybil provides for him.”

“In more ways than one,” the psychologist amended. “And I’ll tell you why—because no two human beings can maintain the ecstatic pleasure-pain state of frenzy that these two have savored together. Look what their life has been like so far! They’ve followed passion wherever it’s led them; they’ve run away from the rules and laws of reality to a world of their own. They’ve made themselves an island where there’s only bewitchment, ecstasy, desire, impulse.

“But for everyone—not just Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, but for everyone—marriage changes many things. There must be growth. Desire must be fused with tenderness, with affectionate companionship. A relationship like theirs—conceived in passion only, fostered by the whiplash of condemnation and dedication to ecstasy—can’t survive the transition to the permanence and patience of married life. Even the marriage vow would have to be amended. Instead of ‘till death do us part’ it would be more honest for them to say ‘Till someone more exciting comes along.’ ”

I couldn’t help laughing, because in that same interview I’d just quoted, Shelley had said of Liz: “With a child like this, it is not surprising that a guy says, ‘I love you’ and she says, ‘Goodbye, Eddie. He loves me.’ The only trouble is that the child will wake up someday and realize that the guy has pockmarks and that he talks about himself all the time instead of about her. Then what’s the child going to do?” It was a keen analysis.

No out for Dickie

I shoved all my clippings into my briefcase and said, “It’s been nice seeing you fellows—but I guess all this speculation is a waste of breath—I’m told Sybil Burton will never give Dickie his freedom. So he can’t marry Liz. So I can’t write my article. . . . ”

“I don’t know about that,” the lawyer spoke up. “Even if Sybil does refuse to grant Burton a divorce, he can still win his freedom from her. Not in England, where the only grounds on which he could initiate divorce action are adultery or, after five years, desertion. But there are many places in the world where he can establish residence and sue for a divorce on something like incompatibility.”

“But couldn’t she contest it?” the psychologist asked.

“The only thing she could contest would be the legality of his residence,” the lawyer answered. “And if he gets good legal counsel, that would be no problem for him. She could demand and get a big chunk of money; she could demand and get custody of their two daughters; but she couldn’t stop him from divorcing her.”

“But if she changed her mind and wanted out?” I asked. “She could get a divorce from Burton in England on the grounds of adultery?

“Is that it?” I asked.

“I didn’t say that,” the lawyer replied. “I said that adultery is one of two grounds for divorce in England. But charging it is one thing, proving it is another. Except, come to think of it, she wouldn’t have to prove adultery. All that she’d have to do is allege ‘inclination and opportunity’ for adultery and then produce witnesses to back her up.

“So I guess you can still write your magazine piece.”

“Yes you can,” said the psychologist, “but I don’t think it will be the same angle as you had in mind. Because I don’t think Richard is going to leave Sybil.”

“Why not?” my lawyer friend and I demanded in the same breath.

“Didn’t he once say that he wouldn’t break up his marriage?”

“True,” I nodded. “And his precise words were: ‘Liz knows that I am not going to break up my family. We always stick together.’

“But that was some time ago. . . .”

“Nevertheless, I seriously doubt that Burton will leave his wife. He’s the kind that loves and runs away so he can live to love another day. And when he runs away, who does he run to? To Sybil. Back to the safety and security of his wife who understands all and forgives all. Can you imagine Liz Taylor, if she became Mrs. Burton, allowing him to stray and play? And then welcoming him back? And can you imagine him accepting a situation where he cant play and stray?”

He laughed. “Write your piece,” he said. “You can even use your same title—‘Why Wedding Bells Toll Liz and Burton’s Doom.’ Just make sure you know which wedding bells you’re talking about.”

I began to laugh too.

“You psychologists are all alike,” I said. “Sly! You mean that the wedding bells which doom Liz and Burton are old ones, right?”

He nodded.

“They rang on February 5th, 1949, right?”

“Right.”

“They rang for Sybil and Richard, right?”

“Right.”

And come to think of it, he must be right—these fellows really do understand people better than people understand themselves.

So this is the piece I wrote.

THE END

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962

No Comments