The Kooky, Private World Of James Hutton

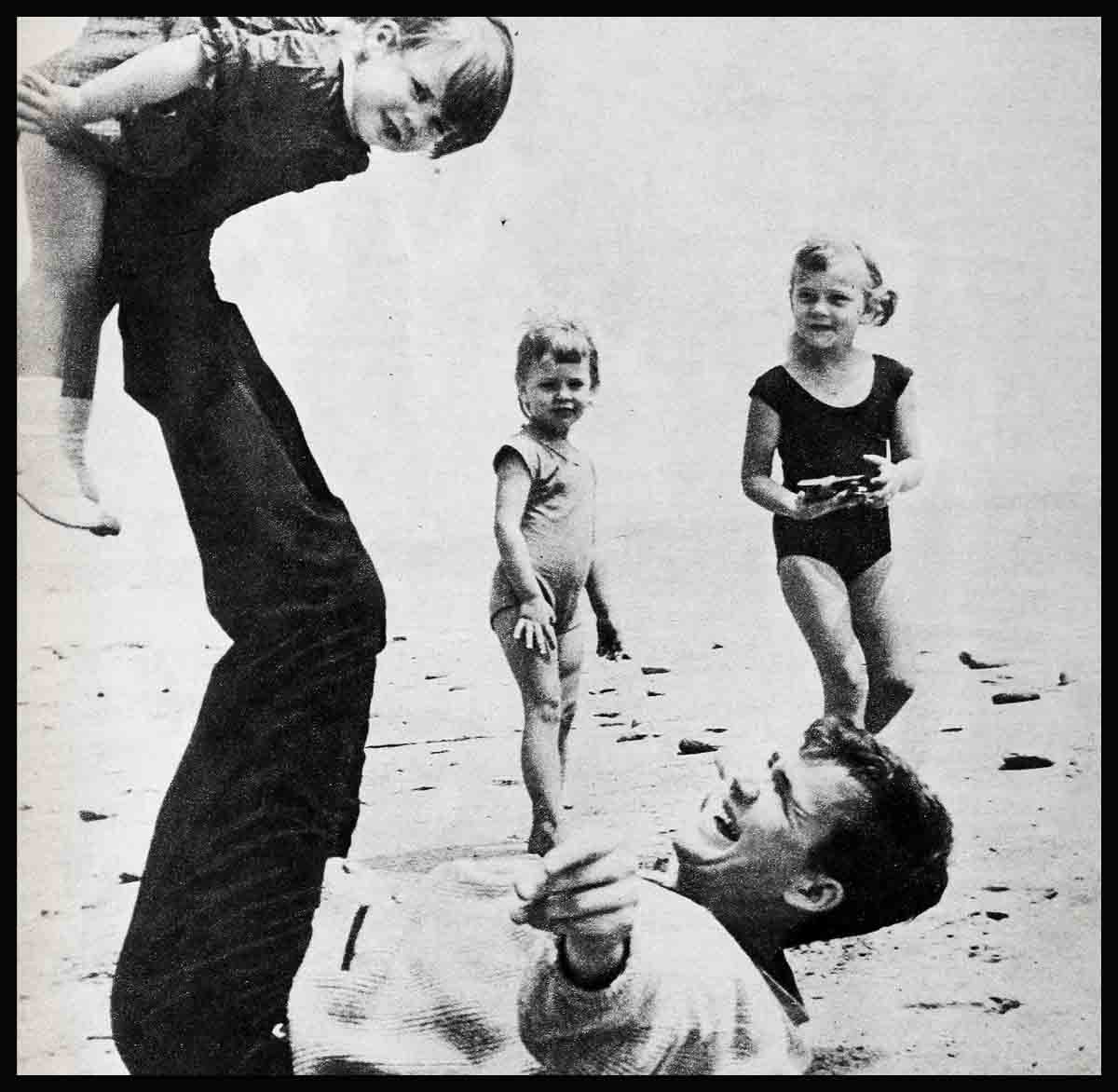

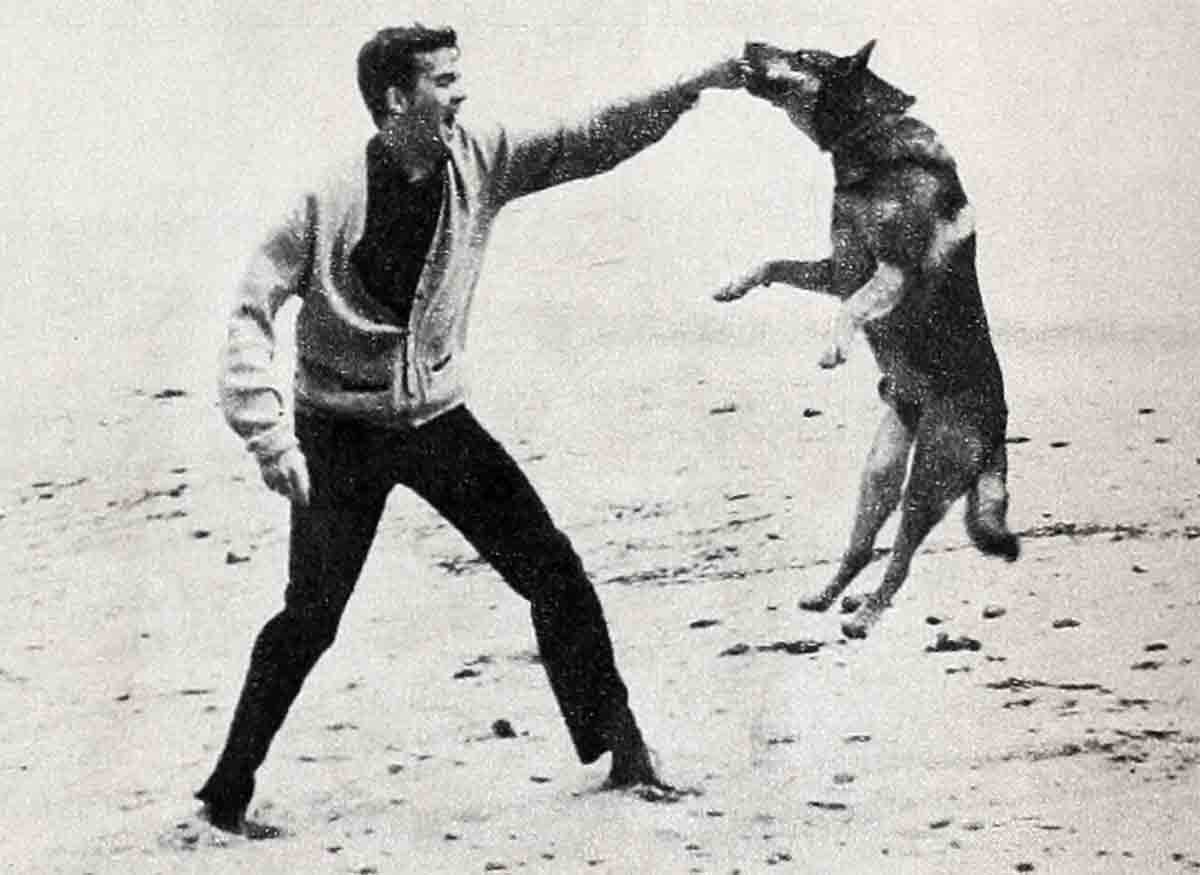

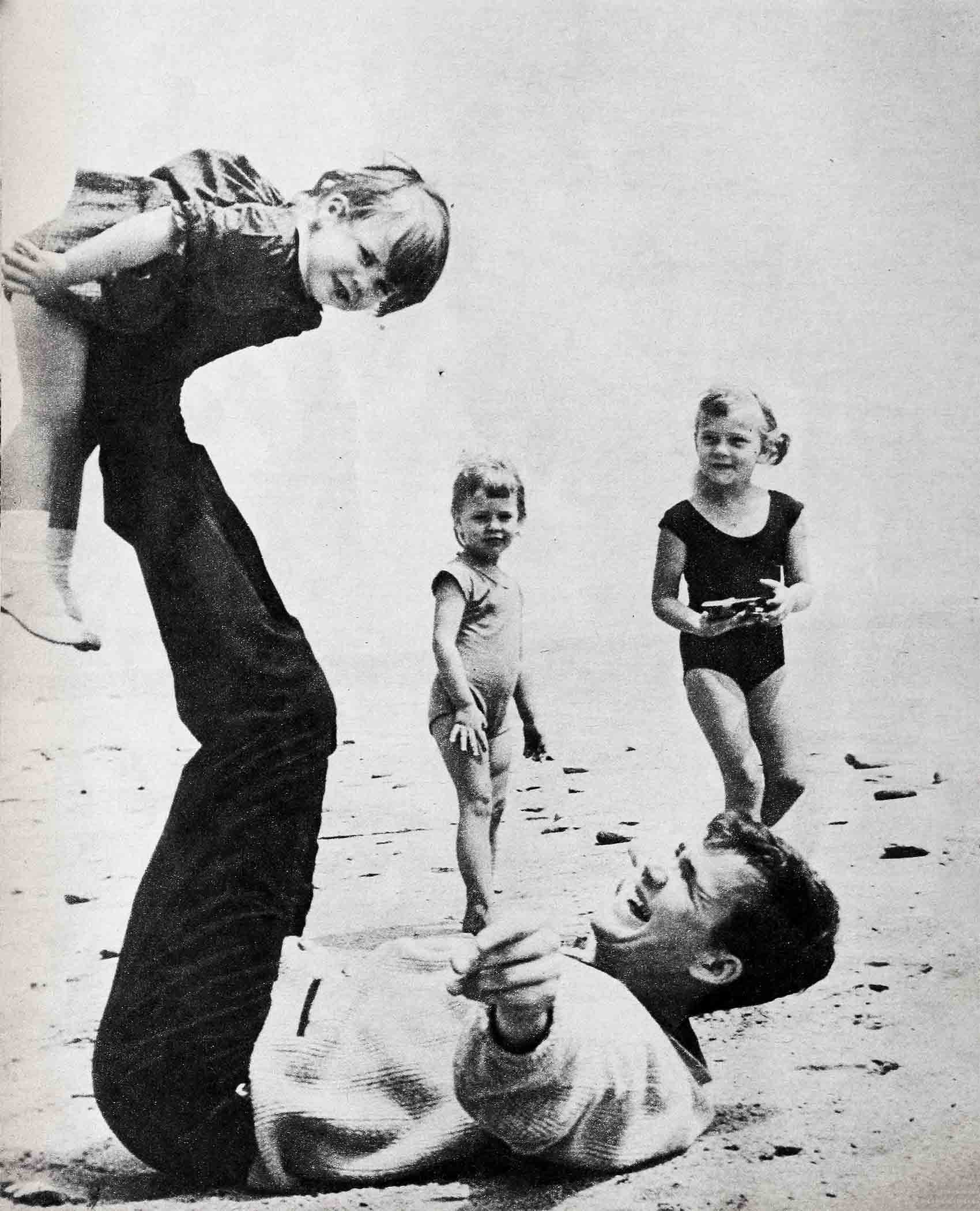

Running barefoot along the beach every afternoon at 1 P.M., accompanied by his two children, a rabbit and a mongrel German shepherd with a mangled ear. Jim Hutton is cocky and contented. . . . On the screen this tall, lanky, twenty-eight-year-old actor (“Where the Boys Are, “The Honeymoon Machine,” “Bachelor in Paradise and now “The Horizontal Lieutenant,” in all of which he played opposite Paula Prentiss) has a loose-jointed air of relaxation which makes it a breathtaking gamble whether he can walk down a flight of stairs without tripping headlong over his own size twelve feet. He seems bewildered by the world and slightly ill-at-ease in it. If things turn out all right in the end—as they always do—it is because his goodnatured, rather bumbling decency has triumphantly muddled through.

Nearly everything about this image—except the decency—is an illusion. The world is Jim Hutton’s oyster, and he has seasoned it to his taste. If he had been unable to become a movie star, he would—as he did once before—merely invent himself one. In his rosy private world he cheats at Monopoly, has dinner at midnight and sleeps until noon.

On the screen his arms, legs and brain seem to be moving, scarecrow fashion, in five different directions. In reality he is graceful and almost sleek, his 6‘ 4“ body aggressively tense. The arms are muscular from hours of volleyball, the legs honed by afternoons of football in the sand. Both arms and legs are controlled by a sardonic, mocking brain as sleek and unselfconsciously cocky as the body.

This is Jim Hutton. . . .

Kind to children and animals, lavishly generous to friends, a “big brown lovable teddy-bear” to his wife, he is constantly striving to be one-up on the more unattractive members of the human race. . . . He delights in fighting City Hall. . . . He refused to marry while in the Army, forcing his future wife to commute to Germany in order to see him, because “Jim didn’t want anything he loved to be contaminated by contact with the Army.” . . . The practical joking he has engineered includes informing a friend who had spent one self-conscious day in a nudist camp that his picture had been published in a sunbathing magazine.

The invented star, Anthony “Rex” Wrayne, was manufactured for the 1957 Berlin Film Festival. For two days he shared spotlights and newspaper headlines with Gary Cooper, Maria Schell and Glenn Ford. Hutton rented a Mercedes Benz and a portable refrigerator stocked with Scotch and ice. The car was stocked with the refrigerator, a languid private wearing striped satin trousers (to play the part of Wrayne) and one fat imitation Hollywood agent. Hutton, dressed in three sets of long underwear and chewing a full pack of gum, ran alongside the Mercedes as Wrayne’s bodyguard.

Three of Hutton’s friends were waiting in the Festival lobby. The two girls began to scream, “Rex Wrayne, it’s Rex Wrayne” as soon as the Mercedes stopped. An imitation announcer pushed Glenn Ford aside to dangle his imitation microphone in Wrayne’s face. Within three minutes, 2,000 people were shouting, “Rex Wrayne, Rex Wrayne, Wir wollen Rex Wrayne.”

The shouting didn’t die down until the next day. When it did, Hutton was no longer a Private First Class. But by this time he was an old hand at losing stripes. Once—while on KP duty in the officers’ mess—he had wondered what would happen if he put alum in the stew. When the Commanding Officer’s lips unpuckered long enough for him to speak, Private Hutton found out.

His practical jokes have an aptitude for hitting psychological sore spots, but none have been vicious or bitter. Because everything he does, has what co-star Paula Prentiss calls “a warm and little-boyish quality mixed with something very cocky.”

She adds, “Jim is ambitious. Very, very ambitious.”

And yet it is not the usual kind of Hollywood ambition.

“I’ve been around too long to make predictions,” says one Hollywood executive. “Nice guys lose their balance. Their egos mushroom and their marriages go sour. I’ve been around too long to take a chance on anyone. But I’d almost bet it won’t happen to Jim. He’s got something solid, as though he’s built on granite.”

Actors who have reached Hutton’s position midway up the ladder usually have a Corvette and a Cadillac, a charge account at Romanoff’s and an $85,000 house in Beverly Hills on which they still owe $78,640.

They know what they want

Hutton and his wife Maryline share a 1959 Ford, a taste for spaghetti and a rented three-bedroom house on the beach, fifteen miles west of Beverly Hills. Their objets d’art are an upright piano from some forgotten saloon, 500 intellectual books and a stuffed lion stolen by Jim from M-G-M. Their background music is the bullying roar of the surf that not even $2,000 worth of stereophonic recording equipment can drown out.

It is not that Hutton is penurious or even thrifty. What close friend Arthur Levinson calls his “wonderful spontaneity and generosity” makes him almost too free with money. His friends are showered with gifts. He pays a notoriously high rental for his beach shack. Yet his dog was bought for five dollars at the pound.

“I want to live the way I want to,” he says. “I will never buy things for use as status symbols—because we don’t need props. Nor will I be embarrassed because I have something expensive that I enjoy.”

Until noon the beach house seems deserted. Even two-year-old Timothy and shy three-year-old Heidi sleep half the morning. When Jim finally staggers out of bed. “It’s growl time; it’s bear time. We have coffee and glare at each other for an hour.” I Only after his two-mile run and then a pound of sausage for breakfast, does his body seem to become attuned to the day.

“The Huttons are night people,” he says mockingly, his unmanageable soft brown hair falling into his eyes. And from 2 P.M. until 2 A.M. the house is jumping with volleyball players, football players and good conversation. The closest the Huttons come to formal entertaining is a keg of beer, a plate of cold cuts on the table at midnight and a game of charades with George Peppard, Jack Weston and half a dozen other friends.

At charades, Jim is unbeatable. His unselfconscious command of his body extends to the gesture of a fingertip. If the game is Monopoly, he always loses. He is a shrewd, arrogant player—and his arrogance makes the others unite to defeat him. When it is obvious that he is going to lose, his hot temper boils over and he often angrily refuses to finish the game.

His delicately balanced temper explodes a dozen times a day, scorching everything in the room. But the children seem strangely untouched by it. Blonde and barefoot, their fair skins sunburnt even in winter, they crawl unconcernedly into his lap.

“I love my kids. . . .”

The mockery fades from his eyes, the wryness from his voice as he strokes their hair. “I love my beach. I love my great big hunting lodge of a house. I love playing volleyball in the sun. I love my kids. I love having bodies around. Animals and children growing. This sounds hopelessly square I know, but this is how I get my kicks.”

And Maryline adds swiftly, “He wants his family. He needs his family. He’s never had a family, you know.”

His parents separated soon after he was born. He has seen his father—a professional Army officer who graduated from West Point in the same class with Eisenhower and Omar Bradley—only twice. He hopefully imagined himself as having been born in a sloop off Kowloon, of a father who was a dragoon and a mother who was a white slaver. In actuality, his parents had both worked on newspapers during the period between World Wars I and II, and had met in a police raid on a saloon during prohibition.

Hutton has little to say about his childhood in upstate New York except, “I was disliked. I was quite often miserable. I was a rebel. I was never one of the boys until I bought my way in by becoming a sports writer in high school and memorizing every book of statistics published on every sport including hockey and lacrosse.” He still delights in disconcerting strangers with such questions as, “Who were the Window Breakers?” (Answer: New York Yankees, 1927).

“My mother was a dear, sweet woman,” he says, “but I was her only son. . . .” Then the mockery breaks to the surface and he adds, “She brought me up to be a nice guy, but I became left-handed instead.”

At seventeen he left home—a nice, polite Catholic boy—with a journalism scholarship to Syracuse University. The smell of freedom was like catnip. He lost his scholarship by casually flunking three of his courses the second semester. To stay in school he spent his weekends digging ditches and his nights unloading bananas. But he had already begun to “get my kicks by deflating people.” He was “dismissed in disgrace” the middle of his sophomore year for what must still remain an unprintable practical joke.

Less than a week later he was handed over to the Jesuits at a strict Catholic College—Niagara. Not quite knowing what to do with him, the priest in charge deposited him in a vacant role in a religious play. The taste for acting remained long after his removal from Niagara “for purposely losing my trousers” at an extremely inopportune moment.

This time he didn’t bother to go home. He hitched a ride to Greenwich Village. “I thought all you had to do to be an actor was to be there, in New York. I didn’t even try to get work. I just waited to be discovered.” In order to live, he cashed in his insurance policies. When the money was gone he stole bananas in Bleeker Street and brought them as gifts to his landlady. Since she had a penchant for using bananas in everything from sandwiches to stews, his gifts occasionally served to make her forget that he was behind in the rent. When even her patience ran out, he enlisted in the Army. It was December, 1955. “I had nothing to do for Christmas. And besides, I was starving. At least in the Army I would get something to eat.” (Despite the fact that he was starving, he did not lose weight. Nor have the gourmet eating experiences of Hollywood as yet added an ounce to his 178 pounds. His weight has remained exactly the same for ten years.)

He applied for Special Services, was accepted and—when he reached Berlin—discovered that “Entertainment” meant arranging canasta and scrabble games for the men. Hutton responds to challenges like a child to a new toy. He immediately set out to test himself.

A one-play actor

He would like to produce plays, he told his Commanding Officer, a Major. For his first play, he said, he had chosen “Harvey.” He neglected to mention the fact that this was almost the only play in which he had ever acted.

Looked at askance “because the Army equates rank and ability,” he was reluctantly given authorization. He renovated an old theater and put on “Harvey” for three nights. It was not exactly professional theater, but it was three more nights of theater than they had ever had before, and he received a Letter of Commendation from a General. When he flashed the letter at his Major, he was given permission to continue.

For the first time in his life, he actually began to study acting. He spent the next two years working with the best private teacher he could find. During those two years he produced, directed and acted in five plays. His last play, “Career,” won a European award for GI plays. He also fell in love and became a movie actor.

Her name was Maryline Poole and she came to Berlin to get a job as a lighting technician and to “break the bonds of landed, middle-class gentry in Connecticut.” She was in Berlin only one month, but he fell in love. “That’s all there is to it. I just fell in love.” Articulate about almost every other subject, he will not or cannot say more about this one. And Maryline—quiet, gentle—will only add, “I knew I wanted to marry him after one week. I fell in love.” When she left, he told her he’d see her in two years and marry her. Then he set about becoming a movie actor.

Douglas Sirk was directing “A Time to Love” in Germany, and he was casting his bit parts there. He saw Hutton in a play and offered him a role if Jim could manage to get to Nuremberg. Jim used charm, perseverance and two years’ leave, but he reached the location in time.

It took twenty days to shoot his five minutes as a neurotic Nazi who commits suicide. When Universal-International saw the rushes, he was offered a contract. “Just come to Hollywood when you’re discharged.”

He was released from the Army on December 13, 1958. On December 15 he was married. Two weeks later they flew to California.

But Universal-International was no longer interested in contract players. M-G-M was, but they didn’t quite know what to do with this one. . . . He lay on the floor of a pad in “The Subterraneans,” hiding behind a beard. He became the father of a daughter. He was loaned out for a few television shows. He played volleyball on his beach. He was almost sorry he hadn’t followed his original plans to go into business as a Professional Hoaxster.

A huckster of hoaxes

“We were going to get the alumni lists from all the Ivy League schools,” he admits. “These guys have a million dollars, a wife, nine mistresses, a weighted pool table, three or four houses, and they’re bored. We were going to send them letters saying we would invent any legal or not too illegal hoax for a price. And,” he still adds wistfully, “it would have been worth the time even to have failed at it.” But then Joe Pasternak asigned him to “Where the Boys Are,” and the rest is current Hollywood history.

He has been untouched so far by his success “except that I can now indulge my passion for long-distance telephone calls. And. unfortunately, I still have several friends in Berlin.”

But he is aware of what can happen to people who are touched too quickly and too heavily by success—and of how to avoid it. While Timothy paints grape jelly designs on his elbow, he squints against the afternoon sun and says, “Jim Hutton the actor is a different person from Jim Hutton the husband and father. To me, acting is a job. The notoriety, the adulation, the expensive free dinners are merely part of the job. And when I come home, I want an onion sandwich.”

He wants something else, too. And. significantly, his largest gratitude to Hollywood is for giving him the opportunity to afford the luxury he wants.

“I want six children. And if I get to be a big big star, I’ll probably lose my head completely and want half a dozen more!”

He rubs the grape jelly off his elbow and seems magnificently calm as he contemplates the future.

THE END

—BY ALJEAN MELTSIR

Jim Hutton can be seen in “The Horizontal Lieutenant” (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.)

It is a quote.PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1962