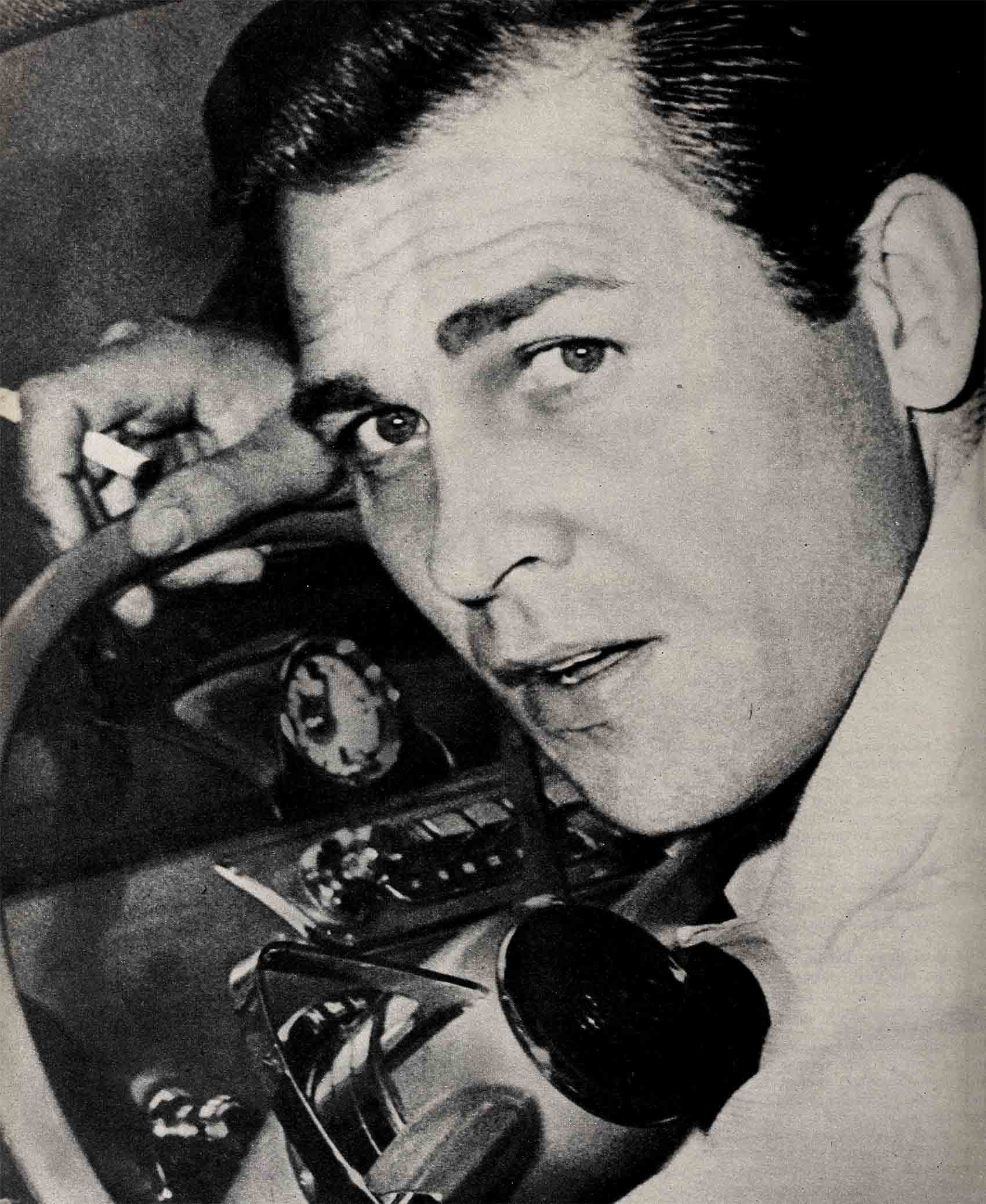

Howard Keel’s Untold Story

STEADY, POWERFUL, EFFORTLESS-SEEMING, Howard Keel’s voice surges out as if singing came as naturally to him as breathing, as if he had been singing easily and from the heart all his life. But it didn’t happen that way. Throughout his childhood, into his early teens, the people of his home town never suspected the wealth of music hidden inside him. It. was hidden, thoroughly; it came out first, eerily, in a recording sent home under dramatic circumstances long before Howard became famous.

Some Hollywoodites might argue that the early muteness of his singing voice is all of a piece with the present-day Keel, the man who has been called too reserved, even stand-offish. That judgment is not and never has been accurate. True enough, Keel does insist on keeping his private life to himself; he has steadfastly refused to allow any publicity focusing on his home and his family.

But publicity is one thing and friendship is another. At no time in his life has Howard Keel been the sort of person who recoils from human contacts, who wants to live withdrawn. Even more than the average man, he has known what it is to need friendship. His need has been answered; he has welcomed friendship; and he has given it freely in return.

From Gillespie, Illinois, to New York City to London, there are many, many people who have known him as a good friend. You have to go to these people to get the true and complete picture of Howard Keel. Those who knew him in the English theatre and movie world can tell you what he was like as an American in a strange country, as a man in love—after one unsuccessful marriage. Those who knew him in New York can tell you about that first marriage and the brief romance that followed. Those who knew him back home in Gillespie—who never suspected then that he could sing—can now tell you why, unlike most singers-to-be, he kept his gift hidden so long.

The story begins in Gillespie. A boyhood playmate now lives in the white frame cottage that used to be home for Howard, his mother, his father and his brother. On pleasant, tree-shaded Madison Street, the house—like the town as a whole—no longer reflects the threat that once brooded over it. This is a coal-mining town. While mining remains a hard and hazardous trade, its dangers have been somewhat reduced, and the shadow of the depression has lifted.

But the atmosphere was different when Howard was a little boy and his father worked in the mines. The unhappy figure of the elder Keel is very much alive in the memory of Gillespie. Homer Keel was a handsome man, big and swaggering. That swagger, his townsmen finally realized, hid a bitter and rebellious spirit. Maybe there was music locked inside him, too. He tried his hand at playing the trombone, but, the local music teacher recalls, “Homer Keel never blew a true note in his life.”

In his mind, he must have heard the true notes, lyrical and beautiful, out of his reach. As a youngster, he was restless, though he came of a solid, steady, God-fearing family. He joined the Navy and went off to see the world. But he came back to Gillespie. A letter that the youthful sailor sent to his home-town sweetheart probably provided the reason. Discovered after his death, it was a “nice” letter, the family remembers, expressing a tenderness that all too often, like the music, remained unexpressed.

Homer Keel came back to Gillespie and married the tall, slender Grace Osterkamp. But for the head of this new household there was no “happily-ever-after.” He went down into the mines. While other men worked there doggedly and proudly to support themselves and their families, Homer seemed to feel himself trapped.

So the first son, William, and the second, Harry (later to be known as Howard), were born into a life of tension and hardship. To help keep the home going, mother Grace set up a small paper-hanging business, in partnership with her sister-in-law. This, like all other departments of home-making, was traditionally a woman’s lookout in a town that saw its men come home dead-tired after each shift.

But the rigors of this life were lightened by neighborliness. Shy, quiet little Howard and his more high-spirited brother weren’t left to run wild. A childhood playmate of Howard’s remembers: “Nobody in this neighborhood had ever heard of a babysitter. Our mothers pitched in to help each other.” Two of Grace Keel’s particular friends looked out for her boys while she worked. And there was another ray of light: Howard’s family picked up some added prestige as the only one on the block that owned a car. The Keels were generous with their car; days the mines weren’t being worked, they’d crowd a lot of neighborhood kids in with their own twosome and go for outings. On these occasions, Homer Keel seemed like another person—gay, comradely, full of adventurous stories. But the difference was only temporary.

Finally, the depression struck. Mines began closing. Seeing no hope ahead, the unhappy, erratic Homer Keel died defeated, openly acknowledging his defeat—before the eyes of eleven-year-old Howard. Neighbors remember that they flocked to help Grace, but how the tragedy affected the boy—this, no one knows. Yet surely it must have hurt him deeply. And his older brother grew increasingly restless in Gillespie after his father’s death.

Grace Keel’s indomitable spirit wasn’t quenched. Even now the neighbors say proudly, “That’s when Grace really began to fight.” Young as he was, Howard fought at her side. He and his closest pal picked up a few nickels by “tin-canning.” They made the rounds of the more well-to-do homes and offered to take household rubbish to the dump. Then they sorted out the bottles and sold them.

At least, the family wasn’t fighting alone. There was the ritual of the lunch pails, instance. Every evening, when the miners came home, each child would run to meet his father, shouting, “Whatcha got in your bucket, Dad?” After teasing protests that the lunch pail was empty, Dad would hand it over, and the youngster would dig into it eagerly for the one sandwich that was always saved from the day’s lunch, no matter how skimpy it had been. Howard’s father was never to come home again, but childless miners joined in the ritual, too, saving that one sandwich for youngsters like him. One of his childhood playmates says, “I realize now that those sandwiches must have been musty and stale—they’d been packed away since morning. But it was always the big treat of our day.”

Choicer treats came Howard’s way when he visited Grandma Osterkamp’s farm. The sprightly old lady called Howard and his cousin Oren Osterkamp “my two young mules.” Stubborn, mischievous, the two were always into something—usually Grandma’s jam jar. They were always hungry, even beyond the degree that’s normal for growing boys. On Thanksgiving, Christmas and many Sundays, Grandma rounded up the whole family for huge meals in the big kitchen. Two or three tables of grown-ups ate first; then Howard and the other kids pitched in. His favorite dishes, an aunt remembers, were fried chicken, devil’s food cake and ice cream.

But such dinners were special occasions; at home, rabbit stew was about the best the family table could achieve. Howard used to save the nickels he’d earned “tin-canning” and use them to buy shells for his gun.

From such a hand-to-mouth existence, music might have been the perfect escape. But the way was cut off. In high school, Howard’s cousin Leo Klein, Jr., was a member of the glee club and the male quartet, and Leo’s mother remembers the boy coming home one day and saying, “I feel so bad for Howard. He isn’t going to get into the glee club, and he’s got his heart set on it. I wish there was something I could do.”

Actually, the townspeople’s recollections of this incident differ. Perhaps Howard was turned down; perhaps he shrank from even asking, afraid that his patched blue jeans and blue shirts wouldn’t be acceptable for the club’s recitals, or simply afraid of being turned down. The bitter experiences behind him had given him no cause for optimism, and his schoolmates never had a chance to learn of his hidden gift for song.

Frustrated, Howard sought another outlet, took out his father’s old trombone and tried to teach himself to play it. His efforts weren’t exactly a success. Art Covelli, the young manager of the Lyric Theatre in Gillespie and once a boarder at the Keels’, says, “I can remember the way he would shut himself up in a room and practice on that trombone, and it was awful. But I never once heard him raise his voice.”

Though Art, then only seventeen, making all of $12.50 a week, also had trouble getting by, he could offer Howard another way to escape. Each evening, when the youthful manager dressed to go down and open the theatre, Howard had a newly-shined pair of shoes ready for him. In return, Art gave the boy two passes each time the bill changed. For Howard, they were more than theatre tickets; they were tickets to another, glittering world. But if the movies roused any dreams, any ambitions in this lanky youngster, Howard never spoke about them.

He was no recluse; when the other kids went to the river for a swim, Howard was usually there, one of the best swimmers in the crowd. But when they hung around at their favorite spot by the railroad trestle, drying off, building a camp-fire, talking for hours about their hopes, their plans for the future, Howard was silent.

Yet it wasn’t long before he was on the road to a future the other kids wouldn’t have dared to dream of. Already stretching out toward his present height, the boy was growing too fast. On his uncertain diet, his health suffered. The family doctor advised Grace Keel to get Howard away from the coal dust and the slag heaps into the sun. His older brother had already gone to California. So Grace and her younger son courageously started west.

Letters that came to Gillespie told the rest of the family that Grace and Howard had both found work (though the money was hardly rolling in), that Howard had recovered his health—and that he was taking singing lessons. This last bit of information impressed nobody, until Grace returned to Gillespie to watch at the bedside of Grandpa Osterkamp, who was dying. She brought a record with her, a privately cut record of “The Lord’s Prayer” set to music, and played it for the old man. It was played again at his funeral, and the family and the Keels’ friends made the astonishing discovery. Mrs. Gennelle Abbott Barry, whose mother had been one of Howard’s substitute “mothers,” recalls, “It was weird. I never knew Howard could sing. And then there, in the funeral parlor, suddenly I heard from an amplifier above me this great, rich voice. I recognized it, even if I had never heard it before. It put a chill down my spine, but it was wonderful, too.”

Hearing these deep, true notes, did the townspeople remember Howard’s unhappy father, whose urge to express himself in music had brought forth nothing but discord? Probably not; this voice told them instead that Howard himself must have become a person very different from the youngster they had seen leaving for California. Just how different, they realized when Howard paid a visit to his home town. Early one summer morning, there was a knock at Mrs. Barry’s door, and on her doorstep stood a tall, broad-shouldered, smiling stranger—who was no stranger, she immediately recognized. Before she could rub the sleep out of her eyes, he was inside, shouting, “Anybody up? Who’s got some coffee?”

“We drank three pots of coffee and ate six dozen doughnuts,” Mrs. Barry says. “I went to the store four times. All the neighbors came in. Nobody shut up for two hours, we had so much to say.”

The shadow of his father’s failure had lifted, and confidence was beginning to cast its light on Howard’s life. Still on his wartime job as an aircraft worker, he was a long way from his final success, but now he could believe it might be possible. Perhaps as a mark of this new confidence in his own future, he had taken a wife, and Gillespie met the bride, a tall, red-haired, spectacularly beautiful show girl named Rosemary Randall, who had been in “Earl Carroll’s Vanities.”

Those who knew Howard later, as a newcomer to the Broadway theatre, remember that he and the first Mrs. Keel made a gorgeous-looking couple. Personally, too, they seemed compatible. Not at all the show girl of fiction, Rosemary proved to be a quiet, cheerful-natured “home girl,” who loved to sew and expertly made most of her own clothes.

Raised in a tradition of neighborliness, Howard quickly made friends with his new show-business colleagues. While he was playing in “Oklahoma!” on Broadway, he and Rosemary, Betty Jayne Watson (also in the show) and her husband, Jerry Austen, became a steady foursome. When the budget was flush, they made a Saturday-night routine of going to the swank Pierre after the show. Betty Jayne remembers one gay evening when she and Harry (like most of his old friends, she calls him by his real name) spontaneously got up to sing “People Will Say We’re in Love.”

So far had he come; the music that had been in him from the start was now free to emerge on impulse. Ironically, on this night he and Betty Jayne proceeded to forget the lyrics they sang nightly. Instead of being embarrassed before the Pierre’s patrons, he broke up in laughter—at himself. The shy, retiring young Howard Keel was left far behind.

He was enjoying his new life. But a newcomer to the theatre doesn’t draw a very royal wage, and there were times when the budget was slightly battered. Then, Howard was just as content to go to Childs or the Automat. The two couples had another weekly routine: Thursday night was “Pie Night” at the Austens’, with generous helpings of pie and ice cream for all hands, pleasantly recalling to Howard those feasts at Grandma Osterkamp’s. One quality of his childhood he hadn’t—and still hasn’t—outgrown: a robust appetite.

The friends who shared these happy evenings were surprised when Howard and Rosemary, after four years together, regretfully decided upon divorce. Genuinely hard-hit by the failure of the marriage, Howard became more absorbed than ever in his career.

Through his work, romance appeared for the second time. Blonde, vivacious Mary Hatcher, another “Oklahoma!” colleague, must have seemed to Howard a symbol of the glamorous theatre world. Chiefly, this was a gay companionship. Their roles left little time for real dates; there were usually parties after work, or sometimes they’d just grab a bite to eat. Mary found Howard “the sweetest guy in the world”; in his unfailing thoughtfulness, he impressed her as “a real old-fashioned gentleman.” And he could be “hilariously funny,” she recalls, occasionally making her break up onstage. Never for a moment did she suspect that there was any tragedy in his background.

The romance never went beyond this companionship. After Howard had been shifted to the London company of “Oklahoma!” he seemed to miss Mary very much at first. So Betty Jayne Watson, who was also in the London troupe, reports. But he didn’t spread gloom around. His London home was in a veddy, veddy English block of “flats” (British for “apartments”) Many of the residents had lived there as long as thirty years without doing more than nod to each other in the hallway. But after the boy from Gillespie had been there only a couple of weeks, he might be found playing Canasta with the man upstairs, or running down to have tea with the little old lady on the floor below. Soon he knew everybody in the building.

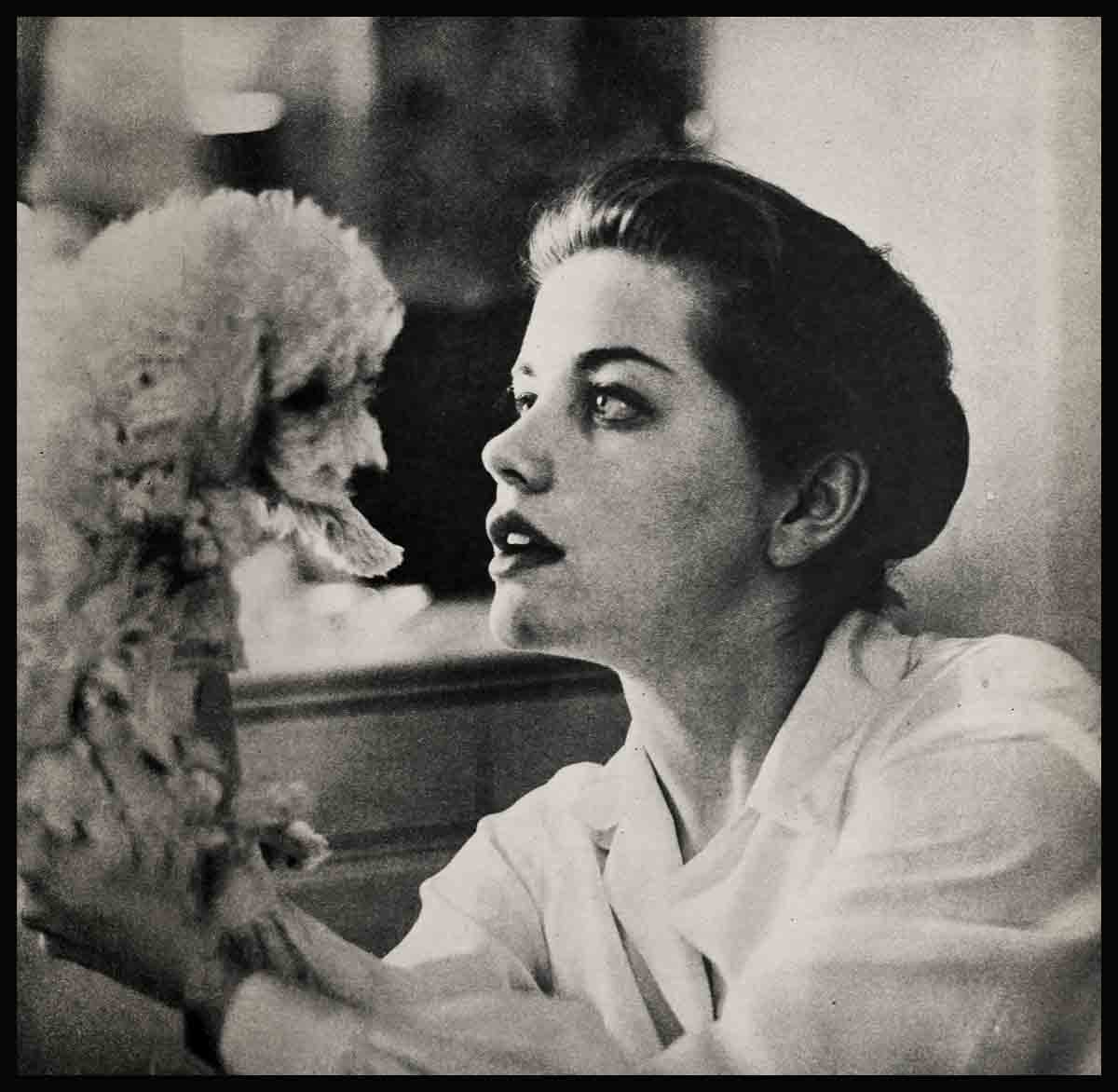

He had started going out with one of the dancers in the “Oklahoma!” ballet. Not so spectacular in appearance as Rosemary, not so famous as Mary, Helen Anderson had a quiet charm, a wholesome prettiness an innate dignity very like his mother’s. Their love was no sudden, overwhelming at-first-sight emotion; it grew slowly and surely, and separation only strengthened it.

While Helen’s work took her back to the United States, Howard remained in England, busy tackling a new field. The British star Valerie Hobson and her producer husband, Anthony Havelock-Allan, ha seen Keel in “Oklahoma!” and drafted h to play the lead in their film, “The Small Voice.” It was his first movie, and Valeri remembers that he was terribly nervous, though he performed like a veteran once he stepped in front of the cameras.

For Howard, this was a chance to make more friends. After a day’s shooting, he’d sometimes ask the rest of the film troupe to come home with him for a supper featuring American-style baked beans, turned out by chef Keel. But on the set there were times when he didn’t do much talking with his co-workers between takes. Then, he’d be seen off in a corner, poring over the latest letter from Helen. The letters, of course, were for his eyes alone, but the photographs that often came with them were proudly shown off all ’round.

For a while after his return to the States, his career and Helen’s continued to keep them apart. The earnest correspondence grew more and more frequent. Once, he went to Pittsburgh to see her, while she was on tour; again, he followed her to Canada. And at last they agreed that they wanted to be together always.

With Helen, Kaiya Liane (going on three and Kristine (four months old), Howard and now has a home life so secure, so precioi that it’s small wonder he is determined to keep it inviolate—especially when you consider its contrast with his own childhood. On the screen, Howard comes across as a personality different from the quiet, home-loving family man. There he is . . . big, handsome, swaggering . . . the music pouring out of him freely and gloriously . . . perhaps the sort of man his father Homer Keel might have been in happier circumstances.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

zoritoler imol

30 Temmuz 2023Nice read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing some research on that. And he just bought me lunch because I found it for him smile Therefore let me rephrase that: Thanks for lunch!