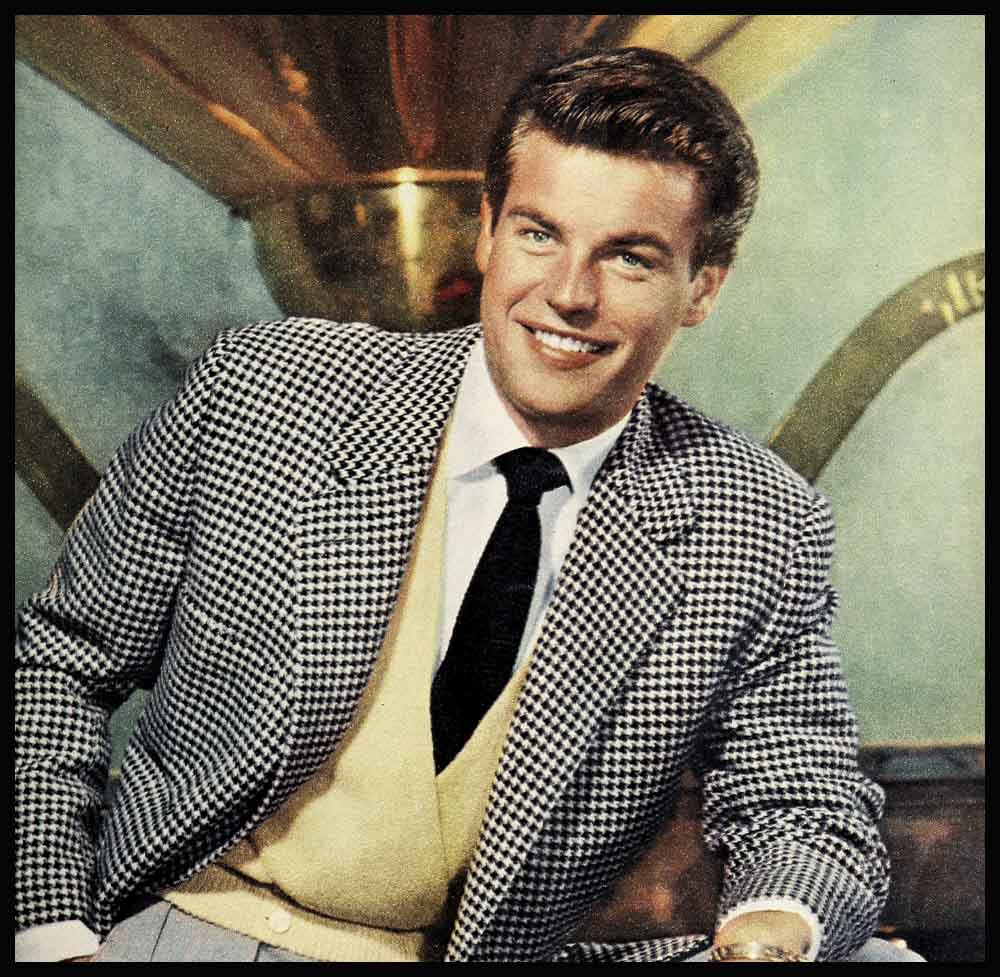

Robert Wagner: Valiant Prince

Today, yours is a magic singing sword. Your subjects number millions throughout the land. They call you “Prince”—and well they should. For you are a Prince of hearts—age seven to seventy.

They call you “Valiant.” And this too you have earned. In the battle of Hollywood, you’ve conquered many comers and you’ve met challenge in any form. Yet yours has been a divided victory, for to win meant defeating, too, the lifetime dreams of those who loved you—exchanging your father’s world of steel for a kingdom of celluloid.

But from childhood, yours was a magical dream not to be denied. It lay within the high walls of a motion-picture studio and in the path of lights that streaked across Hollywood skies. You fought your way into that world, not by joust nor with a sword that sings but with an instinct for acting, a willingness to work and an eagerness to listen and to learn.

As a kid, you spent Saturday afternoons in a Westwood Village theatre, thrilling as thousands of other youngsters thrilled before you to the adventures of Tarzan. You watched, wide-eyed, Johnny Weissmuller’s leaps from tree to tree, bellowing his call of victory. Your top treasure then—a picture he’d signed.

A small voice in the crowd at the Riviera Country Club, you’d cheered a star playing polo. Name? Spencer Tracy—with whom even a dream like yours would not dare say you will later co-star.

Like any other movie fan you stood and stood in the footprints in the forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese. Most of the time you tried Clark Gable’s, thrilled even reading his name scrawled there, but you tried on others like Robert Taylor’s and Tyrone Power’s too. Just for size. You stood there unnoticed, just another boy in blue jeans and T shirt trying on footprints too large for him, dreaming about those whose. names are immortalized in cement. With a kid’s curiosity, you wondered how they’d put them there. . . .

Today you know—every print must find its own way. The story behind any of them could be this story of a movie fan who became a star. Your story, Robert Wagner. And here is your answer. For this is your life. . . .

It begins one day in February, the tenth to be exact. The year is 1930—the same year a serene blond star named Ann Harding is being foot- printed to fame; a tow-haired kid named Jackie Cooper is becoming America’s boy; and a handsome husky from Ohio is fluttering the first of many hearts who will hold him dear through a long motion-picture career. a guy named Gable. Gable is later to play an important part in your own, but you couldn’t be aware of it then. For he biggest news in your block in Detroit, Michigan, is that a son has been born to a paint salesman named R. J. Wagner, Sr., and his lovely wife, Hazel Boe.

In Detroit, the first years of child- hood drag slowly by—while Hollywood footprints a glamorous blond named Jean Harlow and salutes America’s new sweethearts Marie Dressler and Wally Beery for “Min and Bill.” . . .

But in 1937, you too are in Hollywood. Director William Wellman, later to guide your destiny, directs to fame “A Star Is Born” and for “Captains Courageous” Spencer Tracy wins Hollywood’s Academy Award, while Gene Autry is winning the West, armed only with a guitar. Mickey Rooney. as Andy Hardy, is an endearing part of every household in the land. The twinkling feet of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire are still making: history. And a vigorous executive at 20th Century-Fox’s studio, named Darryl Zanuck, is being hailed a star-maker for his faith in unknowns. Like that trusty triumvirate, Tyrone Power, Don Ameche and Alice Faye. Little does he know then that there arrived, special delivery, a seven-year-old he will some day discover. too, and star—initialed “R.J.”

This is the year your parents move to Hollywood. They send you ahead on the train, pinned to you a note of instructions addressed to a matron named Mrs. Pierce, which says, “This is Robert Wagner, Jr. Please deliver to Hollywood Military School.” With you is your sister Mary Lou, age twelve. Your father has stayed behind in Detroit to settle business problems before coming West to become a manufacturers’ representative for the steel industry.

Christmas 1937—a day you will never forget. Santa Claus brings you a squirt gun and a bicycle and an electric train. But better than that—to a lonely little boy—he brings your parents in time for the whole family to celebrate Christmas Eve together in your new Bel Air home.

This really is the year to remember. It marks your first appearance on the stage —in Hollywood Military School’s production of “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” You play Priscilla, complete with costume and curls. But your manly honor is avenged with pathos in the challenging part of the cripple Tiny Tim in the Christmas play. And this is the year, too, that your imagination is fired by the daring and brave exploits of a comic-strip character called Prince Valiant.

Athletics you like. And you excelled in swimming, diving, tennis and track. However, schooling in less active subjects holds small interest for you. Impartially, you try them all: Fairburn Avenue Grammar School, Emerson Junior High, Black Foxe and Harvard Military Academy. Some you leave. Others invite you to. At Black Foxe in Hollywood, they put it politely at the end of the term. If you want to come back, if you will apply yourself, if you will be regimented . . . but, for you, there’s too much marching and too much discipline. At Harvard Military Academy too many demerits mean too much marching. And one day when a classmate delivers a jibe while you’re marching off a few of them, you start a one-soldier riot on the field. Yes, you always were an active boy, as a boyhood friend, John Derek, can well affirm.

“You can say that again, Ralph. R. J. was always plenty fast on his feet. He was three years younger than the rest of our group and small for his age. But he was always tagging along the way a young kid will tag after bigger guys, always wanting to get in on things. We kept our horses at the same stable in Bel Air and rode together. We went to the movies in Westwood and we hung out at the same malt shop. And wherever we went, there with us or ahead of us was R. J. He learned to drive an old ’39 convertible I had. After my break in pictures, we didn’t meet for some time. Then one day photographers were shooting a magazine layout of me in Westwood when I heard his familiar ‘Derr.’ He told me he’d signed with 20th Century-Fox and was prepping for some tests there. I’d spent some time at 20th and nothing had happened. With all the good-looking guys with experience sitting around waiting to work I was afraid it would be the same story for him. My break had come right out of the blue, or I’d still have been sitting, too. I wished him luck in the movies, but I wasn’t too hopeful. Although I should have known R. J. wouldn’t miss out on any action. He never had.”

These are typical teen-age years for you, Robert Wagner. With the help of your pal and neighbor, Bob Green, today Lieutenant Robert Green, U. S. M. C., you build a hot rod combining a Model-A Ford and a Mercury engine. You spend Saturdays sanding it down and knocking off the chrome. It clocks 120 miles an hour at the Lakes. The hottest rod in upper Bel Air. At sixteen, sweater girls are edging out jalopies in your life. Like any teen-ager today, you’re plagued by the folks’ famous last words, “Where are you going?” Also, “What time will you be in?” One morning you get in pretty late. As I’m sure you recall. . . .

“Do I? I’d borrowed my dad’s car for a big date that previous evening. We’d been looking at a few lights of the city and were returning when something went wrong with the fuel pump on the car. I got home at 4 a.m. and my folks were really burned up. They thought mine a very unlikely story and said so in no uncertain terms. Later that day when dad took the car to work he got stuck with the same trouble. ‘I’m sorry about last night, kid,’ he said when he got home. Next day? New fuel pump.”

In 1946, as today, in any teen-ager’s life, truth seems sometimes stranger than fiction.

Your friend, Lieutenant Robert Green, now stationed at Camp Pendleton, remembers still another time when half of Palm Springs was out searching for both of you.

“At least half, Ralph. We were living in Palm Springs and ‘J’ was dating a beautiful little blonde. The four of us went horseback riding early one morning. In an adventurous mood, we didn’t want to stick to the usual trails. We wanted to go where nobody else ever went. And we just about did. We rode clear up to the snow. Tired and hungry, we got lost on the way back home. There was one silver lining. It was so dark, and the girls were so scared they couldn’t keep close enough to us, riding back. We got in around eleven P.M. to find search parties out looking everywhere for us. My father had his own searching party. So did Uncle Bob, ‘J’s’ dad. For a while there—joining the Foreign Legion seemed like a fine idea.”

During your own normal, eventful teen years, a blond star by name of Betty Grable has been pinned up all over the world and her famous legs imprinted in the forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese. A crooner from Spokane, Bing Crosby, has won Hollywood’s highest acting honors for “Going My Way,” and time is growing shorter between now and that fateful hour when you too must decide your rightful destiny. . . .

Through Jack Anderson, a friend of Warners’ talent-head, Solly Biano, you get a reading at that studio. He likes you. but three days later there’s a strike and the studio closes down. To earn spending money you haunt places of employment where you can brush shoulders with the stars. On Saturdays you cover Clover Field, presumably a salesman but usually polishing stars’ planes and firing questions at them. When you won’t accept a tip for polishing Brian Donlevy’s plane, he leaves you the money anyway and says, “Here, kid. Go buy yourself a book on dramatics.” You two are to meet again in a few years guesting on the show at the Stork Club in New York, where you’re making personal appearances with your first starring picture, “Beneath the 12-Mile Reef.”

Through a school friend, Carol Lee Ladd, you meet Alan Ladd and ask his advice. You take a job caddying at the Bel Air Club, making seven dollars a day and a million dollars worth of acting tips from Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Fred Astire and Ken Murray. Eh, Ken?

“As I remember, there were a couple of shots when I needed Prince Valiant for a caddy too, Ralph. Bob was a good-looking kid. Quiet, well-mannered, with a quick alert mind and his eye always on the ball. It was apparent to me then that whatever Bob did he would do his job well. Go the whole distance.”

P.S. However, to you, Robert Wagner, in 1947—that distance still seems too far. . . .

Yours is one of the voices in the glee club of St. Monica’s High School at Santa Monica—remember. . .

“All hail Alma Mater

Green and Gold our colors hail.

We’ll sing to you always

On and on through all the years.

For all the Santa Monica’s

Our love will never fail.

All hail to Alma Mater

To the Green and Gold all hail.”

Here at Santa Monica’s for the first time you feel you have an Alma Mater. You realize the serious importance of an edu- cation and regret those years you might have studied more. Although a non-Catholic, you’re impressed by the unselfishness of the priests devoting their own lives to helping others without monetary reward. One in particular, Brother Hilary J. Deering, a young Irish priest with red hair and humorous brown eyes and a thick brogue, is a great inspiration to you. Long after his own weary day is through, he works tirelessly at night and on Saturdays in the physics lab with you, tutoring you on the alloys and the processing of steel and preparing you for the future. However, at first, yours is a more immediate incentive, as Brother Hilary will remember well.

“Indeed I do, Mr. Edwards. R. J.’s father had promised him a trip East with him during the Easter recess if he mastered his studies of steel. And R. J. really wanted that trip. But as months went on, he matured a great deal both in his thinking and serious application to his work. We spent a great deal of time together. He introduced me to my first Notre Dame football game and to driving in the California traffic. I had driven in Ireland, but I was hesitant to drive here until R. J. got me out into the traffic and gave me confidence. As a student, his increasing application of concentration to his studies was very gratifying. I was amazed from the first—for one who admittedly had made small use of it—by his retentive memory. He was preparing for the steel world then, but instead the celluloid world captured him. . . .”

You, R. J., are impressed by the hours the priest spends preparing you for the business world, and you respond gratefully. According to the high school annual, “The Compass,” your favorite saying this senior year is “That’s very dapper,” and your favorite pastime “listening to Louis Armstrong.” You make the glee club, you’re active in dramatics, in swimming and tennis, and you are touchingly overwhelmed when the students vote you senior-class president.

It’s June 12, 1949—commencement. You’re handed a green leather diploma and you are on the threshold of an exciting new life. A life which will surprise some of your classmates, including Bob Smith—today a very successful insurance man.

“I was in Korea with the Seventh Army when I saw ‘With a Song in My Heart, and realized the shell-shocked soldier was R. J. I hadn’t even heard he was in the movies. In school, he was a devil-maycare, easy going kid. To see him portraying such a serious role—and doing it so well—I was surprised. All the guys thought he was great. I kept thinking I went to school with this kid, but I never realized he had so much on the ball. Yet, when I thought about it, the more I realized it was always there.”

It was always there, all right, and although you make every effort to prepare seriously for the place your father has made for you, your own dream remains. You work in steel mills back East this summer, learning firsthand everything from the furnacing and milling to the marketing of steel. You take a job in your father’s office going after new accounts. He pays you a retainer of two hundred dollars a month and plans to divide the profits with you at the end of the year. For a boy of nineteen this is a bonanza. For your father it means the fulfillment of a lifelong ambition. But you yourself know this is not your life. Nor can it ever be. Your heart is within those studio walls and sound stages you pass on the way to work each day. One night, the night that is to change your whole life, you tell him. Nobody knows better than you, R. J., just what happened that night.

“Looking back now I was pretty selfish, Ralph. I didn’t know then what a blow it would really be to Dad. How many plans he’d made for the two of us. He was disappointed all right, but how disappointed he didn’t let me know then. And me—I was concerned with what I wanted to do. Even though I’m sure he hoped it would prove just a whim, when I asked Dad to back me for a year, he agreed. If he hadn’t, I could have become embittered and resentful, and he could have changed my whole life. What a guy!”

September 1949 and “What a guy!” is right. When nothing happens to help you realize the dreams that mean your own happiness, your father seeks advice from an old friend, director William Wellman, who gives you a double bit in his M-G-M picture, “The Happy Years.”

In your first scene, you play a tough catcher on a kids’ baseball team with a catcher’s mask completely covering your face. You make $37.50 for the day’s work, and, tired but happy, you insist on celebrating by taking your parents to dinner at The Beachcombers Restaurant in Hollywood and paying the check. A few years later, you are to celebrate there another occasion the—most exciting event of your life.

Even behind a catcher’s mask director William Wellman sees great promise in you. Suppose, Bill Wellman, you tell us why.

“Because I made Bob do a bit part that needed an experienced actor, Ralph, and Bob played it like a professional. All I remember advising was, ‘Think you can do it and you can.’ But I can’t take any credit for discovering Bob Wagner. As much as Bob wanted this, he would have stuck to it no matter how long until one way or another he got a break. I tried to get M-G-M to sign him, but they thought I was crazy. They couldn’t see him at all then.”

Yes, despite director Wellman’s personal pitch, the talent department there discourages you, advising you to go to New York and study for two years, get yourself an agent and then come back and talk to them. Nor will Wellman’s agent handle you. He explains kindly that he cannot give you the time and attention a new- comer should have.

Finally, the big management corporation, MCA, agrees to sign you if you will study at Pasadena Playhouse for a year. You arrange to meet at the agency on a Monday morning. But on Sunday night at a friend’s restaurant, the Beverly Gourmet, you’re clowning around and singing with the piano player, whom you know, when a star-maker, Henry Willson, observes and sees screen possibilities in you. He sends a note to your table, saying if you’re interested in being in pictures to bring your father along and come to his office the following day.

“What did you see, Henry, that night that so impressed you?”

“The changing expressions on his face, Ralph. I watched his face mirror every thought and word—this, together with his looks and bright clean personality. Bob has a sincerity and a relaxed quality that comes right across that screen. He has, too, the unusual star-making ability of making every characterization believable while projecting his own personality in every part he plays. Given the opportunity, I was sure he couldn’t miss.”

The autumn days roll on in 1949, and you get that opportunity. You test for the lead in “Teresa” at M-G-M, and out of one hundred fifty tests, yours gets studio raves. Fortunately for you, New York executives decide not to risk using a boy who’s had neither stage nor screen experience, for Darryl Zanuck signs you at 20th Century-Fox on the strength of that same test and puts you successively in top budget pictures—so great is his own personal faith in you.

So in 1949 those studio gates you’ve envisioned swing wide open for you and you step inside the magic never-never land. You’re given the small part of a Marine in “The Halls of Montezuma,” and wisely enough, you know, Robert Wagner, that you too have only just begun to fight.

You earn your studio stripes that first year, working overtime convincing some of the frankly skeptical that this really is your life. That for you acting is no summer inspiration, no game you’re trying for kicks and size. You haunt sound stages from early in the morning when the first crew arrives until the last are light dies. The stages darken and the night shift strikes the sets, but the studio lot is still an enchanted world to you. You spend hours in the cutting rooms, talking to cameramen, rehearsing with the studio drama coach, Helena Sorrell.

Soon stars, producers, directors, gaffers and grips, all of them are with you. Cameramen “reload” to cover you when you fluff a line, giving you time to regain confidence. Gaffers “blow a light” to give you a chance to make another and better take. In “The Halls of Montezuma,” Richard Widmark observes you’re getting lost in a scene as one of many Marines going over a hill and tells you, “Look, kid, take your time. Next take, slow down and stay close behind me.” You do, and the camera is full on you all the way. Dick Widmark puts that close one right in your lap. But he takes no credit for ever helping you.

“If I did, well, it’s easy to help someone you like. You can tell when a kid’s out for a fast buck. Bob was never that way. He was always eager to learn. He had a basic instinct for acting and the talent to get some place. He has a lot of years in this business. I’d have given my eyeteeth to play the part he’s playing in ‘Broken Lance’—and playing well. I remember telling him that first picture I’d be supporting him before I was through. Sure enough, in my last picture at 20th, I’m supporting him.”

In 1951, director Walter Lang and the late Lamar Trotti pick you for the wonderful bit—a shell-shocked soldier in “With a Song in My Heart.” They say it will do a lot for you. And it does. A Bob Wagner fan club forms. You have your own fan publication, “The Wagner World.” Director John Ford casts you as the love interest in “What Price Glory.”

But before his picture rolls, tragedy overtakes you for the first time in your twenty-one years.

You go water-skiing at Lake Arrowhead. Robert Jacks, later to produce “Prince Valiant,” is driving the boat. You and another friend are skiing tandem behind. You fall and his knee hits you in the side of the head, knocking you out cold. Later a doctor assures you there’s no serious injury. But two weeks later, you go to the hospital with a punctured eardrum and a serious brain concussion. You spend weeks flat on your back before you entertain the dark thought that this may well be the end of your dream. For one who’s been so athletic, yours is the tragic thought, too, that there will be no more physical activity. But Lady Luck doesn’t desert you now, and you are to portray just about the ‘most strenuous role ever enacted on the screen.

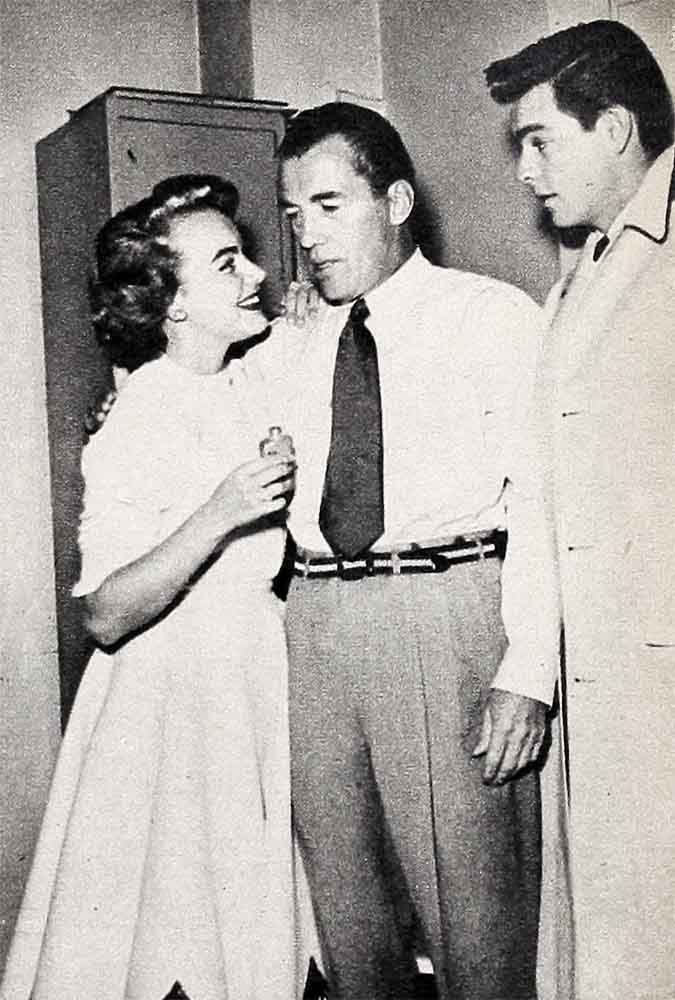

It’s 1952, and with 1953 comes “Titanic.” Darryl Zanuck is steadily shooting you to stardom. Motion pictures have still lost none of their glamour for you. You live, breathe and love your work. During a love scene with Terry Moore in “Beneath the 12-Mile Reef”—but let Terry tell this.

“R. J. surely does take his work seriously, Ralph. I can vouch for that. During an underwater love sequence, a shark came between us. R. J. just held me with one arm and pushed the shark away with the other and went right on with the scene.”

Nobody could blame him for taking that one seriously.

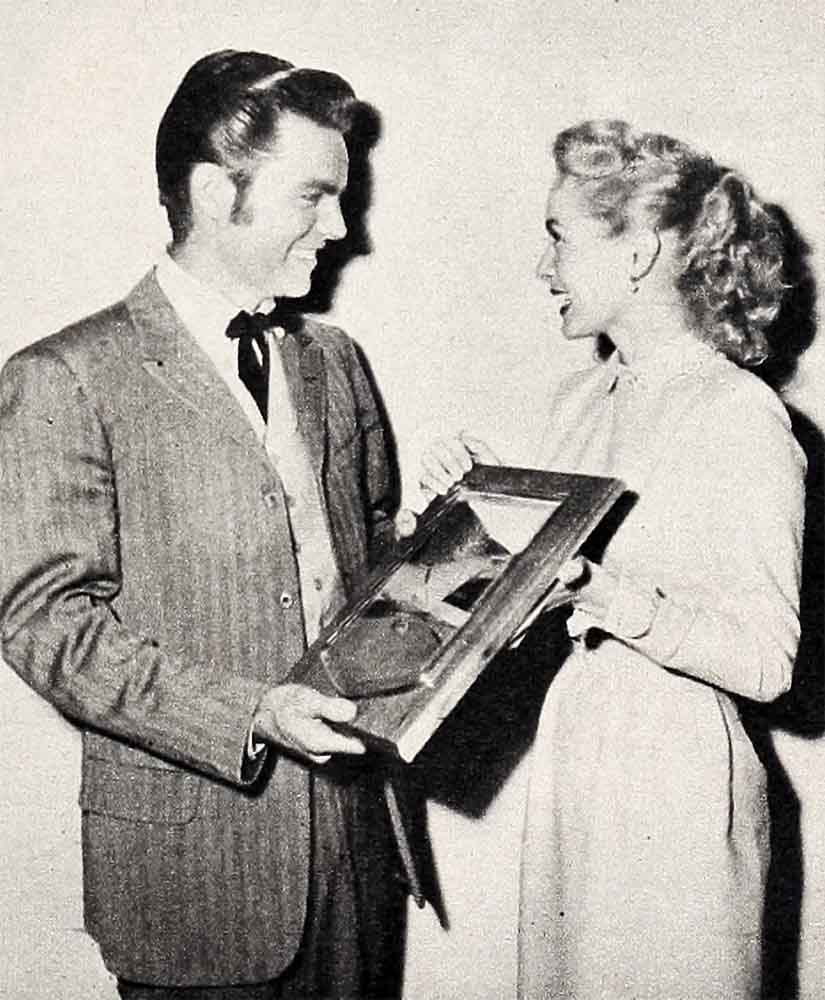

In 1953, you reach full stardom in “Beneath the 12-Mile Reef.” You and Terry Moore make a personal appearance at the New York opening. You’re thrilled by the dazzling marquee and thrilled as a fan of Jackie Gleason’s to meet him and guest in his television show.

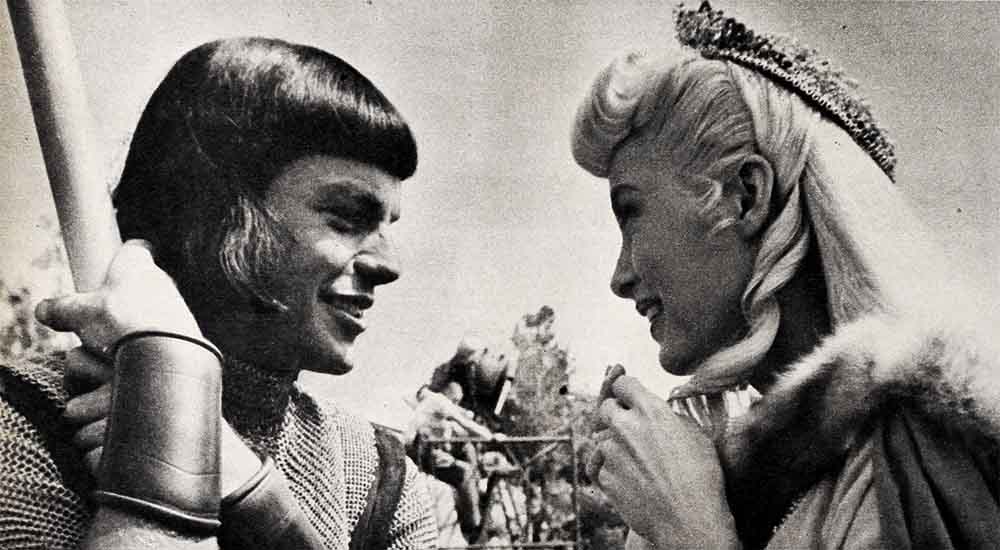

December 1953 sees you portraying your own childhood hero. Producer Robert Jacks picks you for Prince Valiant—a triumph and the toughest of challenges for you. You’re Tarzan and D’Artagnan rolled into one. You scale walls and joust with lances and fight one hundred sixty broadsword encounters. Concerned, both as friend and producer, that one of them will be too broad, Bob Jacks insists you’re taking too many chances.

With the second week’s rushes, Darryl Zanuck gives you a new four-figured contract that guarantees star billing from now on. It will seem true to you when “Prince Valiant” is cut and reviewed.

February 1954, and you are co-starring with Spencer Tracy in “Broken Lance.” King Trace, no less, pays you the supreme compliment you will read here for the first time.

“The kid has the quality of a young Barrymore. His future? Unlimited.”

And now, finally, it’s April 2, 1954, Robert Wagner, the night you’ve been waiting for all your life. The night of the premiere of “Prince Valiant” when a movie fan’s dream is to become a magic reality.

You take your parents to The Beachcombers for dinner, celebrating that other night four and a half years ago when you dined them on your first $37.50 bit pay check. Tonight they proudly celebrate with you the success of a dream that was not their own—your success in the world of celluloid.

At eight-thirty your car pulls up in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Crowds jam the bleachers and the boulevards roar. Arc lights split the Hollywood heavens. As your party steps out on that red carpet, photographers’ flash bulbs are blinding.

Your own throat is too full to speak. You’re the same kid who stood there not long ago trying on those footprints. Tonight the world acknowledged they fit.

This is your night, and this is your life from now on. Prince Valiant Wagner. Long may you reign.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1954