Audrey Hepburn—The Girl, The Gamin And The Star

March 25, 1954. On this night the eyes of the world are focused on Hollywood. The annual Academy Award sweepstakes are about to end with the giving of filmdom’s highest honor—the little gold statuette named “Oscar.” Only tonight, when the time arrives for the final choice of “The Best Performance by an Actress,” the spotlight shifts. Not Hollywood but New York is the backdrop for this suspenseful, exciting moment. Sitting in a gala audience at the NBC Center Theatre, with her mother and her future groom, is the twenty-four-year-old newcomer who, on the strength of her first Hollywood picture, is to win this coveted prize over such competitors as Deborah Kerr, Leslie Caron, Ava Gardner and Maggie McNamara.

I watch as Audrey Hepburn, trembling with emotion, leaves her seat to come on stage and acknowledge the honor bestowed upon her by the motion-picture industry. And suddenly the scene before me recedes in the distance and like a flashback in the movies, the calendar turns back.

July 18, 1951. The setting was London, where Audrey and I met for the first time at a dinner party given in my honor at Mayfair’s most popular private club, Les Ambassadeurs. Faye Emerson, who had just flown over to spend a few days with me, was among the guests. So were Humphrey Bogart, John Huston, Sam Spiegel (who had just finished filming “African Queen”) and Lauren Bacall. My hosts were James and John Wolf of Romulos Films. And they also had two other guests—Jack Dunfee of MCA talent agency and his young client, Audrey Hepburn. Audrey confessed to me later that she was speechless, especially over meeting Humphrey Bogart, whom she had always admired. If anyone had told her then that two years later she would be his co-star in “Sabrina,” she would have retorted, “Don’t look now, but your crystal ball is cracking!”

Of course, the easiest thing in the world to say after anyone becomes famous is, “I always knew she had it in her.” In the case of Audrey Hepburn, however, I climbed onto the bandwagon at once. I was immediately enchanted by her fresh, young beauty and natural charm and felt she had that something extra special that Ellen Terry once described as “star quality.” I didn’t wait until her overnight triumphs in “Gigi” and “Roman Holiday” to discover her great charm.

At that first meeting, I drew Audrey out by asking a lot of questions. She seemed grateful for my interest and answered with the confiding warmth of an old friend. “Everything significant in my life has happened gloriously and unexpectedly—like the trip I am making to Monte Carlo tomorrow,” she told me. “I’ve always longed to go to the French Riveria, but never could afford it. Then this picture, ‘Monte Carlo Baby,’ turned up. I play only a small supporting role, but I never thought I’d even get that.

“The day the producer interviewed me was one of those days when everything went wrong. I had a terrible time finding a stocking that didn’t have a run in it. The zipper got caught in my dress. And when I finally arrived at my agent’s office, the whole interview lasted exactly a minute and a half! I was sure I’d failed.

“I tried to comfort myself by telling mother that if I went to Monte Carlo for this small part, I might miss out on a larger role in London. And anyway, someday I’d make enough money so that we could both go to the Riviera on my expense account. Then suddenly the phone rang and I heard those four words that are the sweetest music in the world to every actress, “The job is yours!’ ”

As we parted at Les Ambassadeurs that night and Audrey went home to pack for Monte Carlo, neither of us dreamed what “glorious and unexpected signifiance” the trip was to have for her. The story is old-hat now, but it will be forever new to Audrey, because it changed the entire pattern of her life.

It was while she was shooting a scene for “Monte Carlo Baby” in the lobby of the Hotel de Paris, that Colette, the famous French novelist, stopped to watch Audrey from her wheelchair. The next day she sent for her and announced, “Vous étes ma Gigi.” And Audrey, who speaks French fluently, didn’t need an interpreter to explain that she was Colette’s choice for her “Gigi,” dramatized by Anita Loos into a stage play for Gilbert Miller.

Thus it happened that within four months of our first meeting at that London dinner party, Audrey had attained Broadway stardom in “Gigi.” She had also been screen-tested by Paramount for the lead opposite Gregory Peck in “Roman Holiday,” under a long-term contract. She had become engaged to one of London’s most eligible and popular bachelors, James Hanson. She had just celebrated her twenty-second birthday.

When Audrey arrived in New York in November, 1951, to open in “Gigi,” she ell as madly in love with our town as we did with her.

“I even enjoyed going to the dentist here,” she told me. “Because when I look out the dentist’s window, I can see Central Park and it’s so breathtakingly lovely!” We were having tea in her suite in a small residential hotel in the East Fifties.

I was delighted to find that Audrey’s overnight stardom in “Gigi” and the overwhelming adulation that had come to her since our first meeting hadn’t changed her a bit. She was just then being sought out by all the hostesses in town and pursued by the El Morocco stag line. But Audrey, brought up by a Dutch mother in war-torn Holland, learned discipline at a very early age. She refused to be distracted by social things.

In her work, she drove herself relentlessly. And although her natural reserve sometimes resented it, she accepted with good grace the demands made upon her time for photographs and stories about herself in magazines and newspapers. She rightly saw it as part of any successful actress’ career.

She steadfastly refused, however, to break into her time for social engagements during the week. And her weekends were devoted to her fiancé, James Hanson, whose business kept him in Canada a great deal. If he couldn’t fly to New York to be with her, she would grab a plane after the Saturday night performance and fly to him.

Audrey, let it be noted, has always been a one-man woman. When she came to London and landed her first job in the chorus of the English revue, “Sauce Piquante,” she fell in love with a young Frenchman who was playing the lead. He was beaucoup crazee about her, too, and persuaded the producer to take her out of the chorus and allow her to share a number with him.

This was the puppy love of two earnest youngsters, with stars in their eyes—for the marquee of a theatre! It was beautiful while it lasted, and when it became “just one of those things,” it was “goodbye, dear, and amen.”

And when Audrey closes a chapter, it stays closed. She may look as fragile as a lady in a Fragonard painting, but she has an implacable will.

Jim Hanson, unlike Audrey’s first love, was not of her theatre world. Hanson was a highly successful businessman, young, wealthy, socially prominent. As an attractive bachelor, he had all doors open to him. And one of those doors led him to Audrey Hepburn.

Audrey’s career is the all-absorbing passion of her life. Yet, she seems to feel the need of “a man around the house.” Sometimes these interests are incompatible, as proved true with Audrey’s second love. Her engagement to James Hanson lasted a long time, but their plans for marriage grew dimmer and dimmer as Audrey’s career took her further and further away from him.

“When I marry James, I want to give up at least a year to just being a wife to him,” Audrey told me during one of our tea sessions. “I can’t do that now with the road tour of ‘Gigi’ ahead of me, and then the ‘Roman Holiday’ film on location in Italy.

“James is being wonderfully understanding about it. He knows it would be impossible for me to give up my career completely. I just can’t. I’ve worked too long to achieve something. And so many people have helped me along the way, I don’t want to let them down.”

It was this growing knowledge that Audrey wasn’t ready to sacrifice her career to marriage that helped soften the blow of their broken engagement a few months later. Audrey and James have remained good friends. When Audrey became Mrs. Mel Ferrer in Switzerland last September, James was one of the few of Audrey’s exclusive circle to be invited to the private ceremony. He appreciated Audrey’s thoughtful gesture, but sent his regrets—an Englishman to the manner born.

Speaking of Mel Ferrer brings me to another flashback. The time is May 31, 1953, and the setting is again London—two days before the Coronation. Greg Peck, who had a charming duplex flat in Grosvenor Square, invited me to drop by for cocktails. When I arrived, I was delighted, but not the least surprised, to find two other chums—Audrey and Mel.

Audrey and Greg had developed a mutual admiration society during the filming of “Roman Holiday.” In fact, there were even veiled hints that their screen romance might continue after the cameras had stopped grinding. As for Mel, he and Greg had a common bond of interest. Both had for years shared a desire to bring legitimate theatre productions to the California Coast—a dream that had become a reality at the La Jolla Playhouse every summer since 1947.

In the spring of 1953 Mel was filming “Knights of the Round Table” at Elstree, near London. Greg’s flat was “home” to Mel. And it was perfectly natural that through Greg, Mel met Audrey Hepburn for the first time.

But if anyone had told Greg then that with this introduction he brought together a future man and wife, he’d probably have said, “You’re off your rocker!”

As a matter of fact, if I’d asked Audrey at the time, “Would you want to marry a man twelve years older than yourself, twice divorced and the father of two growing boys?” she’d have been equally incredulous.

But when we lunched together the day after Greg’s cocktail party, I didn’t ask her this sixty-four-dollar question—not only because there was no hint of a budding romance then, but also because Audrey is the kind of person who instinctively puts up the barriers between herself and anyone trying to pry too far into her personal affairs.

Outwardly Audrey is all warmth and femininity—the kind of helpless, cuddly creature that appeals to the protective instinct in every man and woman. Yet, beneath that exterior, she has the inpenetrable emotional reserve of an introvert—intensified by the stolidness of her Dutch heritage. In her physical make-up, too, she embodies this dual personality. At home, sitting on the floor in beautifully tailored slacks, turtle-neck sweater, no shoes, with her feet curled up under her, she has a gamin tomboy quality. In public, at a first night or on the dance floor, she looks every inch the real counterpart of the reel princess in “Roman Holiday.” The key to her universal appeal is that she conforms to no set mold.

Audrey is not beautiful by the technical standards of perfect beauty. She once confessed to me that she used to be so self-conscious about the unevenness of her front teeth that she would rarely smile. Yet, when she made “Roman Holiday” and Paramount offered to cap her teeth so that she would look like all the other Hollywood glamour girls, she politely refused. Nor did she let the make-up department pluck one little hair from her heavy brows. Her eyes, of course, are her most outstanding feature—they are hazel and deepen in color when she expresses emotion. Her figure does not have the feminine curves of a Monroe or Turner, but she is the envy of every woman who suffers from overweight. Yet, believe it or not, I have seen her resist the most tempting dessert to guard against one inch more on her extraordinary size eight.

When I first met Audrey her hair was much longer. Then she cut it short for “Roman Holiday”—then shorter for “Ondine”—so that now, in the amusing description of photographer Cecil Beaton, “The woods are full of emaciated young ladies with rat-nibbled hair and moon-pale faces!”

Is it any wonder that Mel Ferrer fell head over heels in love with such a provocative, desirable creature? Mel has always been attracted to glamorous, successful women. As a matter of fact, his wife Frances, whom he married when he was a struggling young actor and she a struggling young artist, is the only woman I know whom Mel romanced before she was a “Name.”

I can also easily understand why Audrey succumbed to Mel’s charm. Because Mel has that rare quality in an American male—he makes a woman feel like a woman. Perhaps it is his Puerto Rican heritage, but he has this quality which is fast dying out in our atomic age.

He also has another wonderful gift; he is a stimulating talker. On an evening I spent with him shortly after that first meeting of Mel and Audrey, we discussed the theatre, pictures, travel, art and people. In the last bracket, there was talk of Audrey, her unaffected charm, her innate breeding and her inevitable Hollywood success, once “Roman Holiday” was released. But even when Mel told me he was taking Audrey to the theatre the next night, I didn’t attach any special importance to it. Because at that time there wasn’t any.

Although Audrey’s ambition was to be a stage actress, her theatrical experience had been limited to one West End revue. And since she had neither the time nor the budget to go to the theatre, she had only seen about a half-dozen plays in all of her years. But she was so anxious to learn, that—even when she was in the chorus of “Sauce Piquante” and doubling at Ciro’s afterward—she had daily lessons in dramatic art. Her coach was one of the finest character actors in the English theatre—Felix Aylmer.

In that summer of ’52, when Audrey suddenly found herself for the first time with the leisure and the money to go to the theatre, she was avid to see everything. Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt were playing at the Phoenix in Noel Coward’s “Quadrille.” I knew that Audrey had never seen this magnificent team so when Noel graciously sent me his house seats, I invited her to go with me. Of course, she was enthralled by their magic spell, and later, when I took her around to the Lunts’ dressing room to meet them, she was like a wide-eyed child meeting Santa Claus for the first time. When Alfred asked her about “Roman Holiday,” she was flabbergasted that the great Mr. Lunt had even heard about her. She would have been even more stunned if anyone had told her that the following year on November 20, while she was in Hollywood, co-starring with Humphrey Bogart in “Sabrina,” she would send me the following wire: “Darling Radie, now that the play is all set, I’m able to give you the good news. It’s ‘Ondine,’ and guess who is going to direct me—Alfred Lunt! Needless to say, I am happy beyond words, especially at being given the opportunity to work for and learn from him. How wonderful that you introduced me to him in London. Much love. Audrey.”

No one ever came to Hollywood for the first time under more fortuitous circumstances than Audrey Hepburn. “Gigi” had brought her Broadway stardom. “Roman Holiday” now made the whole world hers. And nowhere in the world is success worshipped more than in Hollywood. Everyone from Adrian to Zanuck wanted to meet her. The local and foreign newspapermen—all of them—wanted exclusive interviews. Paramount spread out the red velvet carpet for their new queen.

How did Audrey react to this wild acclaim? She was grateful for such recognition of her work, of course, but she was scared. In the first place, she couldn’t believe she was that good—and this was no phony modesty. She was petrified of the blaze of public interest in which she suddenly found herself.

In London, she had lived with her mother in an unpretentious walk-up flat, off Park Lane. In New York, she had lived alone in a small hotel suite. In both cities, she had led as normal a life as the schedule of any actress will permit. But in Hollywood, a word may be magnified into a quote—or a misquote. Would Hollywood try to change her? To devil her life with false or little authenticated stories? In London, libel laws prevented your name from being linked erroneously in a romance item. Audrey knew she would have no protection in Hollywood for an item like this: “Can’t wait to meet Audrey Hepburn and find out if her kisses with Greg Peck are for real!”

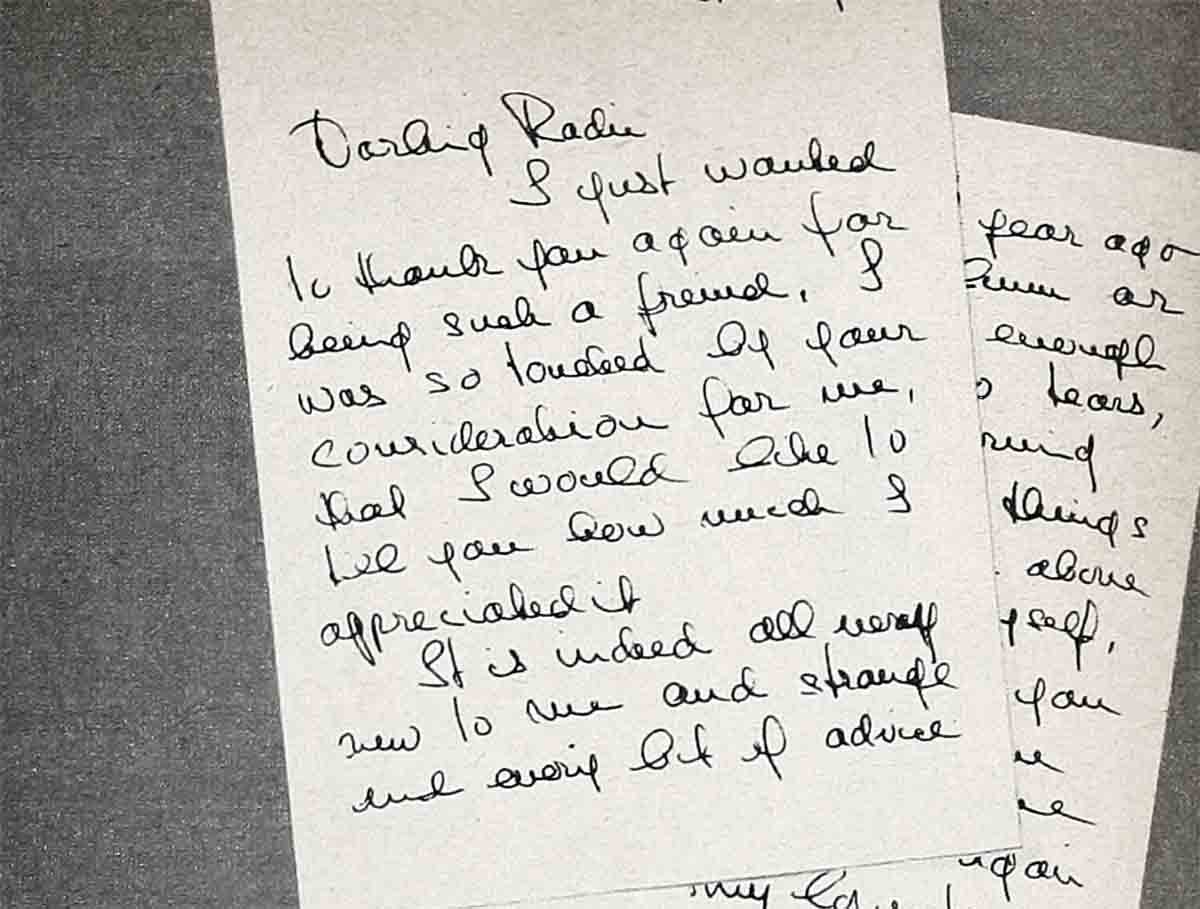

When she expressed some of these fears to me, I advised her to go see the head of the studio, Don Hartman, and tell him exactly how she felt. I was sure he would be in complete agreement with her desire for the kind of publicity in keeping with her personality. Romantic innuendos and whether she wore falsies and slept in a double bed with pajama tops or nighties were definitely not that kind of publicity. Audrey took my advice and after her talk with Hartman, she wrote me:

“Darling Radie: I just wanted to thank you again for being such a friend. I was so touched by your consideration for me that I would like to tell you how much I appreciated it. It is indeed all very new to me and strange and every bit of advice is so helpful. A year ago a line in a column or a rumor was enough to reduce me to tears, but I am learning fast and taking things in my stride and above all keeping to myself. I remember asking you about this when we first had lunch one day. Thank you again, Radie. My love to you. Audrey.”

But as soon as “Sabrina” went into production, Audrey’s fear of Hollywood quickly disappeared, and she began to love her new home. After the fog and rain of London, she lapped up the California sunshine. She leased a charmingly furnished apartment, with a patio and swimming pool, which she shared with her secretary-companion, and she hated to leave, except to go to the studio.

And since she adored her director, Billy Wilder, and the whole company and crew of “Sabrina,” she hated to leave the studio!

When she came East to do the yachting sequence on location in Westchester, she only had one day off. On that day she called me to lunch with her at “21.” I found her thinner, which was understandable when she told me that she stayed on at the studio after the regular day’s shooting for private ballet and singing lessons. But Hollywood’s make-up department hadn’t changed her one iota. Neither had her success. She was still the same sweet, unspoiled girl who had enchanted me at our first meeting. I would have staked my life that she always would be.

Two months later, Audrey wrote me that she was coming to New York to start rehearsals for “Ondine.”

“Am looking for an apartment,” her firm, familiar scrawl informed me. “Mother arrives the 17 of December for her first visit to America. Imagine the excitement! I plan to spoil her as she’s never been before! . . . I read your column faithfully, and you are so wonderful to root for me the way you do, always in the way which makes me happy. You will hear from me soon again. Lots of love. Audrey.”

I wrote back that a friend of mine, with a lovely Park Avenue apartment, was leaving for Europe, and perhaps Audrey could take over her sublease. Back came Audrey’s reply, “I think I will let you guide my domestic life, too. It will bring me the same good fortune as my career.”

When Audrey arrived in New York this time, Mel Ferrer was with her.

He had seen “Ondine” in Paris, and it didn’t take long to persuade Audrey that she would be the perfect heroine to his “knight errant.” With Audrey in the title role, any management would have grabbed this property. The Playwright Company were the lucky winners.

Audrey, in appreciation of Mel’s “package deal,” not only shared co-starring billing with him, but insisted on splitting her per cent of the gross with him! It was then that I began to realize, “If this isn’t love, what is it?”

As the two of them plunged into rehearsals, they were inseparable, on-stage and off. Actually, it wasn’t difficult to understand the bond that brought them together. Aside from Audrey’s undeniable physical beauty, and Mel’s well-practised charm, they both have a relentless ambition for their careers. Only their motivations differ.

Audrey’s is inspired purely from a creative urge to express herself with the God-given talents with which she is blessed. The knowledge that never again can she enjoy the privilege of anonymity is a penalty she willingly pays for Fame.

On the other hand, Mel wants to take advantage of every door leading to his success. The spotlight, publicity, fan worship are welcome dividends that pay off at the boxoffice. He isn’t satisfied with just acting. He wants to direct, write and produce, too.

His contagious enthusiasm and authoritative background knowledge found a soul mate in young Audrey, so anxious to absorb everything that would help her career. Remember, too, that both Mel and Audrey are cosmopolites who are equally at home with the International Set abroad, as they are with their New York and Hollywood circles over here. Both of them speak several languages fluently, even though they soon discovered that “I love you” is the same in every language!

It wasn’t long after rehearsals of “Ondine” started that the Broadway grapevine stage-whispered that Mel wasn’t seeing eye to eye with Alfred Lunt’s direction. I remembered Clifton Webb once telling me, “I consider myself a veteran in the theatre, and yet, if I had the chance to be directed by Alfred Lunt, I would consider it a privilege.” I couldn’t believe that Mel didn’t feel the same way. And knowing the respect Audrey had for Lunt’s art, I felt that if there were any argument, she would never uphold Mel against Alfred. I called Mel direct to check on the rumor, and he said it wasn’t true. I was happy to deny it for him, but very unhappy when I learned later he hadn’t leveled with me.

I didn’t see Audrey during this hectic time of rehearsals, but she would call me from the theatre whenever she had a breather. However, I caught up with her mother, the Baroness Ella van Heemstra, for lunch at Sardi’s.

The Baroness, from whom Audrey inherits her patrician beauty, kept me fascinated with stories of her earlier life, and Audrey’s. It seems that the Baroness and her sister both wanted to study for the opera. But in those days in Holland, the stage was forbidden to girls of good family. So the two dutiful daughters married and gave up their career ideas. But the Baroness vowed that if she ever had a talented child she would do everything to encourage her. During the war years the Baroness, who had divorced Audrey’s father, found herself and her eleven-year-old daughter trapped in occupied Arnhem. They lived in the family castle, but it might just as well have been a dungeon. They had no light, food or heat. Even their bicycles were confiscated by the Germans. The Baroness told me that her sister’s husband, Audrey’s favorite uncle, was shot right before Audrey’s very eyes. A harrowing experience for anyone, but to a sensitive eleven-year-old, it was a nightmare she never forgot. That Audrey survived this terrifying loss of her childhood and grew up into such a happy, normal young girl is a tribute to the courage and love of her mother.

By one of the miracles of fate, a great Russian ballerina, who had married a Dutchman, was a nearby neighbor in Arnhem. And in those war years, whenever Audrey wasn’t too weak from lack of food, she studied ballet with this superb teacher.

“This was the only sunshine that lighted the clouds of those dark days!” the Baroness said to me. “Now to see my dreams for Audrey fulfilled beyond my fondest hopes is sunshine to my heart every day!”

The most distinguished ermine-and-white-tie gathering of the season flocked to the 46th Street Theatre the night “Ondine” opened in February ’54. As the curtain rose, my hands were clammy with nervousness for Audrey. But my eyes instinctively looked for her mother, sitting with James Hanson (who, again, as in the case of the “Gigi” opening had flown over from London to surprise Audrey, even though he was no longer her fiancé). All three of us were sharing Audrey’s first-night jitters, as she waited in the wings for her entrance.

When she had opened in “Gigi,” as a young newcomer to Broadway, Audrey felt that if she got by with passably good notices, she would be happy. Instead she got raves. “In “Ondine,” as a highly publicized Hollywood star, Audrey knew she would have to win critical and public acclaim, or it would be a demoralizing setback to her career.

But Audrey, as usual, underrated her special magic. If she had been the film critics’ No. 1. favorite after “Roman Holiday,” she was now the drama critics’ newest Valentine. They embraced her with the kind of glowing notices that every actress dreams of and few achieve. The audience cheered and bravoed, hoping that she would take one curtain call alone. But with every bow, there was Mel, always at her side. Finally, when the house lights were on, and the audience still applauding madly for Audrey, Mel held up his hand to hush the house for a curtain speech. An acknowledgement to his lovely co-star, we all assumed. But we were wrong. Instead, we heard a flowery expression of thanks to Alfred Lunt, and since this completely professional audience was well aware of the backstage differences between Ferrer and Lunt, this public recapitulation was received with slightly raised eyebrows!

I didn’t happen to like Mel in “Ondine.” I didn’t feel that he played his role with a bravura style of acting it demanded. There were others who shared my opinion. But, because I didn’t want to hurt him, I hedged in my comments in my Hollywood Reporter column. I merely wrote, “I wish as a ‘knight errant,’ Mel Ferrer hadn’t been such an ‘errant knight’ and had given Audrey Hepburn a curtain call alone, when the first night audience so obviously wanted it.” For some inexplicable reason, Mel never forgave me this criticism.

It was incomprehensible to me that Mel could so quickly forget all the complimentary things I had written about him through the years and hold this one criticism against me, although this has been known to happen in many a columnist’s career.

It was not, however, until four months later—a period when Audrey had avoided me—that she spoke of Mel’s continued antagonism over lunch one day. She was obviously very embarrassed as she confessed that Mel had convinced her that I had betrayed my friendship with him in my column, and I might do the same to her. In other words, she wasn’t to trust me, now that she knew no columnist could be a friend, too. I felt that Audrey realized how unfair and unkind she had been to me in this purely hypothetical mistrust of me. She begged me to understand the emotional pressure of the last year and kept repeating, “Please believe I haven’t changed. I’m still your friend.” When I returned home that evening, there was a lovely bowl of flowers waiting for me, “With love from Audrey.”

I was leaving for London the following week, and we made a date for another luncheon visit, the day before my flight. A few days later, Audrey called to break it, explaining apologetically that Willie Wyler was in town and she had to see him for business reasons. But could she stop by my apartment and wish me “bon voyage?” I was going to be out all day, last minute shopping, so I said I’d stop by her dressing room before the evening performance. We chatted like old times, until her fifteen-minute curtain call.

Audrey didn’t come to London during my stay there, but flew directly to Switzerland for her much-needed holiday. I was back in New York when the news came of her marriage to Mel in the little Swiss village of Bergenstock. I cabled them my best wishes, and I meant them sincerely. If Audrey has found the happiness she is seeking with Mel, that’s all we who love her want for her. What are their future plans? Audrey’s recent note from Rome, where they are still honeymooning at this writing, made no mention of when she would resume her career. But I know her next assignment is another Paramount picture in Hollywood. I also know that in ’56, she wants to take time off from the screen and return to the theatre for a season of repertory at Stratford-upon-Avon or the Old Vic in London.

And sooner or later, there will be an independent picture deal co-starring this new Mr. and Mrs. team on the screen or stage, too. Future plans also include a Hepburn-Ferrer “production” in the nursery.

Let’s hope that all of these plans materialize. But let’s hope, most of all, that the chapter closes, “And so they lived happily forever after!”

THE END

—BY RADIE HARRIS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1955

graliontorile

20 Haziran 2023Regards for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting information.

vorbelutr ioperbir

8 Temmuz 2023Great write-up, I am regular visitor of one?¦s blog, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.