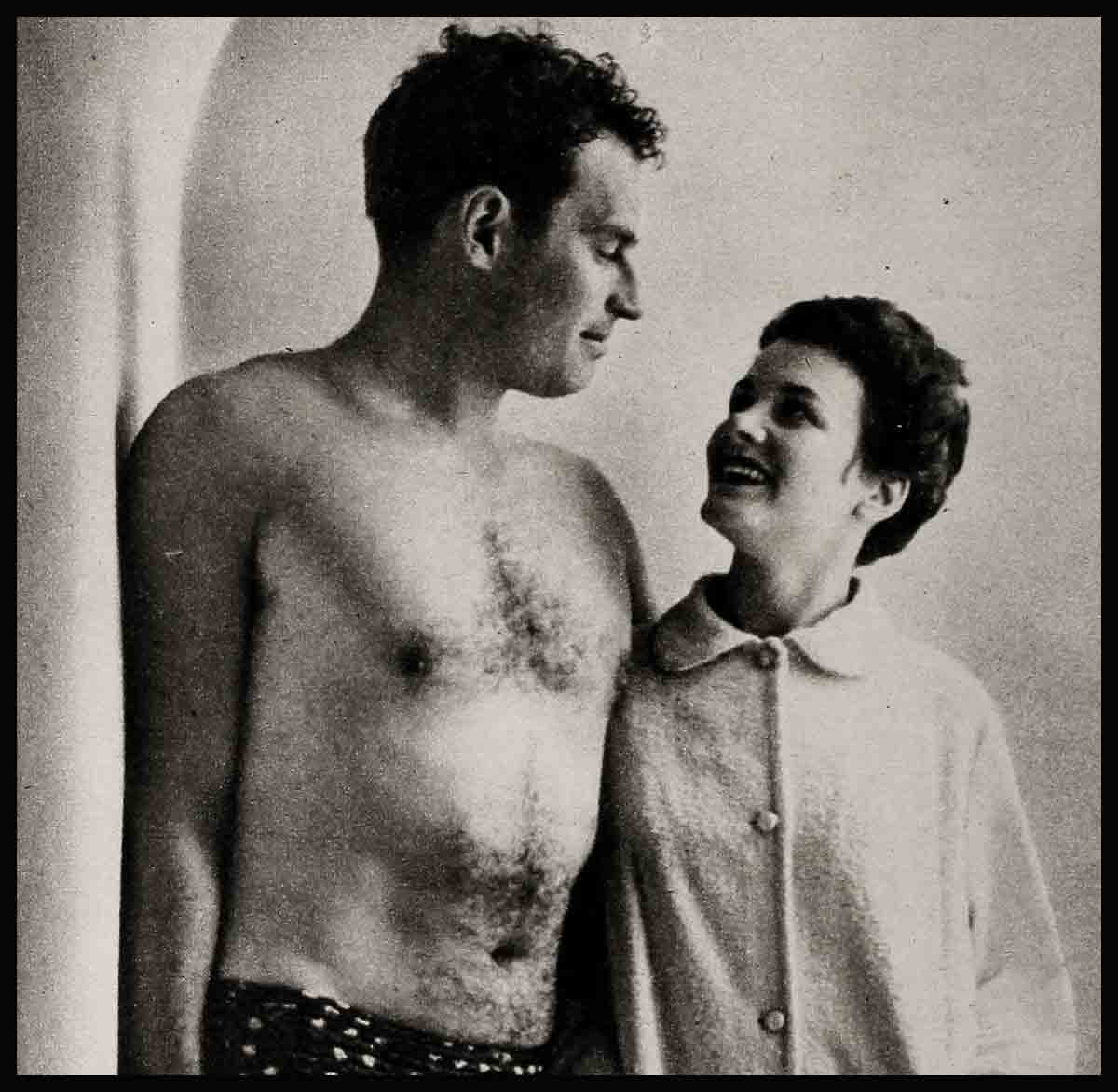

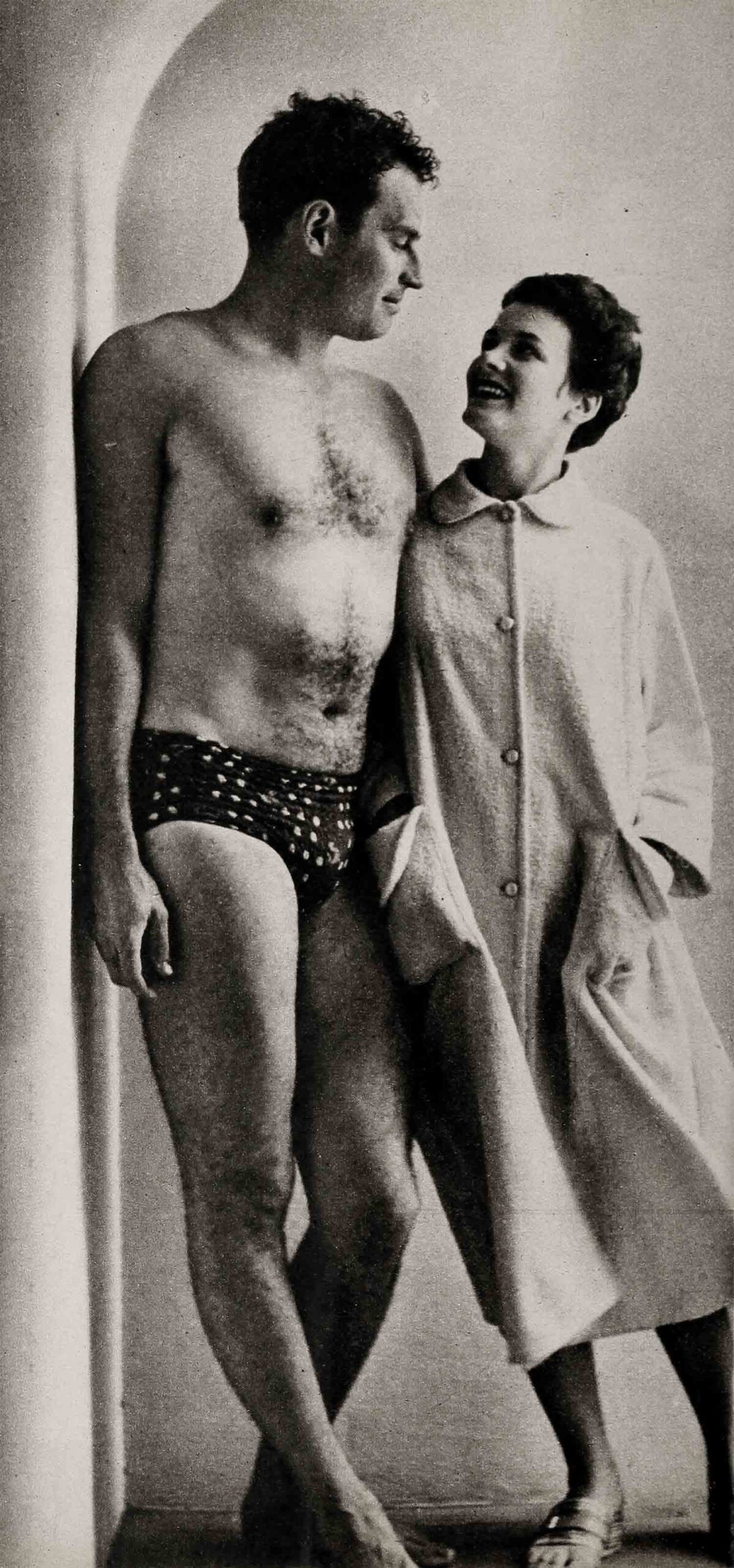

“Hi, Honey-So Long, Dear”—Charlton Heston & Lydia Clarke

One lonesome evening, a dainty, brunette doll called Lydia Clarke was happily watching her favorite actor, Charlton Heston, perform Shakespeare’s Macbeth on a television program. Suddenly she screamed, clapped her hands over her hazel eyes and blanked out, mercifully.

Mrs. Heston had swooned at the sight of a grisly head—unmistakably her husband’s—hacked off at the neck, dripping blood and lifted up by its familiar curls before her very eyes.

Luckily, Lydia came to in time to see the man she loved taking bows with a perfectly sound Adam’s apple and telling his public he hoped that they had enjoyed the show. Obviously, one of these—his wife—had not. Lydia hadn’t known about the flesh colored, rubber head, carefully molded to a perfect likeness of Chuck’s features for that gory touch of realism. Her big, lovable, exasperating husband had neglected to tell her about that.

Fortunately, Lydia Heston’s recovery from the shock was complete, although she wasn’t quite herself for days. She had time to reflect that the long distance married life of two actors left a few things to be desired. At other times, Charlton Heston has had the same misgivings.

On a recent night, for instance—this time when Chuck was in Hollywood and Lydia in New York—he put in a midnight phone call and soon heard the familiar feminine tones of his wife saying, “Hello . . . hello.” But at the same time he heard an unfamiliar baritone saying the same thing. Chuck clicked the operator impatiently. “Something’s wrong,” he complained, “Try it again.” She did; same result. Back came the wifely greeting—and the same disturbing man’s voice too. Well—you know how husbands are.

“Look,” barked Chuck, “I may be old fashioned—but just what the hell is a man doing in your apartment at three o’clock in the morning?”

There was, Lydia came back sharply, no man in her apartment, but obviously some obnoxious male character on her party line. “Get off!” yelped Chuck to the unknown kibitzer and was invited in colorful language to get off, himself. So all that came of that tender long distance contact was a three-cornered hassle, rising blood pressure and some sleeplessness for the Hestons.

Both Charlton and Lydia Heston can rattle off half a hundred upsetting domestic contretemps like those, brewed by the zig-zag, water spider pattern on their ten years of hectic, but still happy, married life. There was the time for example, when Lydia, after a year-and-a-half’s separation from her Charlie, came back from a Chicago run with Detective Story—all set for a few cozy months of married life in Manhattan. When she boarded the train, she was sure Chuck would be still safely involved in his TV work.

But when he met her in Grand Central Station he was lugging a suitcase.

“Well!” she gasped, “where are you going?”

“Hollywood! Got a contract at Paramount.” It was the first she’d heard about that. What’s more, his west-bound train left in exactly one hour—so the long anticipated home life turned out to be a couple of stools at a coffee shop while crowds of people scuffed suitcases around their toes, redcaps dashed in and out and the clock hands circled ominously.

About the time you read this, too, the big, blond bruiser will be giving a hasty bear hug to his cute life’s companion and dropping her off a flight from Bermuda in Chicago before he hustles back west to finish High Andes in Hollywood, while Lydia opens on a Windy City stage in The Seven Year Itch. For all she knows, the run might be seven days, seven weeks, seven months or seven years—but the itch to get back together will still be there, as indeed it has been ever since the Hestons swore their hurry-up marriage vows back in 1944—and two weeks later lost each other for two long years via Air Force duty in the Aleutians for Chuck. Their “Hi, Honey—So long, Dear” domestic pattern has been more or less the same ever since, and seems a good bet to continue.

Meanwhile, they’ve got two separate sets of furniture on two coasts, two Packards parked 3000 miles apart, two complete wardrobes, right down to lipstick and shaving kits, two maids who’ve never seen each other, and sets of unacquainted friends in the three first cities of the land.

Now, all this sounds like a sure-fire formula for domestic disaster. It’s certainly true that the Hestons have had the odds stacked against their married life. “Goodnight” is too often relayed over telephone wires, and on at least one anniversary, Chuck and Lydia actually passed each other in mid-air, headed in different directions. It’s true, too, as previously hinted, that there are moments of long distance stress and strain, misunderstandings, and mixups brought about by their stop-and-go home lives. Not long ago, Chuck invited forty-five people to a gala dinner completely unknown to Lydia, then breezed off east on some career summons. She was amply paid back for the day she hopped away from New York, leaving him to prepare food and drink for the eighty-five guests set to swarm into their flat.

But none of these harassments seem to have altered the firm status of a happy union which one of their best friends, Jan Sterling, calls, “so perfect it’s a little embarrassing.” There’s only one word to explain it—love—but it’s two kinds of love, love for each other and love for the thing that’s terribly important to them both—acting.

That might sound a little on the serious side, considering the subjects—a deceptively Dulcy faced girl who’s as full of beans as a Boston belle and a supercharged husky whom one critic recently described as “A 3-D Mister Coffeenerves.” Chuck and Lydia Heston maintain a life of love on the run without wilting in the race because all their lives they’ve never been in love with anyone in the world but each other. And all their lives they’ve never really wanted to do anything else but act.

Seventeen-year-old Charlton Carter Heston first met Lydia Clarke, or rather stared boorishly at the back of her pretty neck, in a drama class at Northwestern University. He had never had a date in his life. “And, to tell the truth,” says Lydia, “he looked it.” She got this impression when she turned the neck in surprise at a statement Chuck made regarding a play they had studied, and about which the instructor asked for critical comment. The voice back of her boomed, “It’s skeletal,” as Lydia remembers, and when she swivelled around to see just who came up with that, she thought, “Brother, so are you!”

Charlton had gone to a one-room school in the backwoods of the Michigan peninsula where the ink froze in the inkwells. That’s where he was born and spent his boyhood. It’s a boyhood that Chuck Heston still looks back on today with a fond longing tugged by strong family roots. The 1300 acres and the hunting lodge, that he recently bought for a getaway is part of a whole wild county which his speculator grandpa bought up for taxes years ago. Russell Lake, on his place, is named after Chuck’s dad.

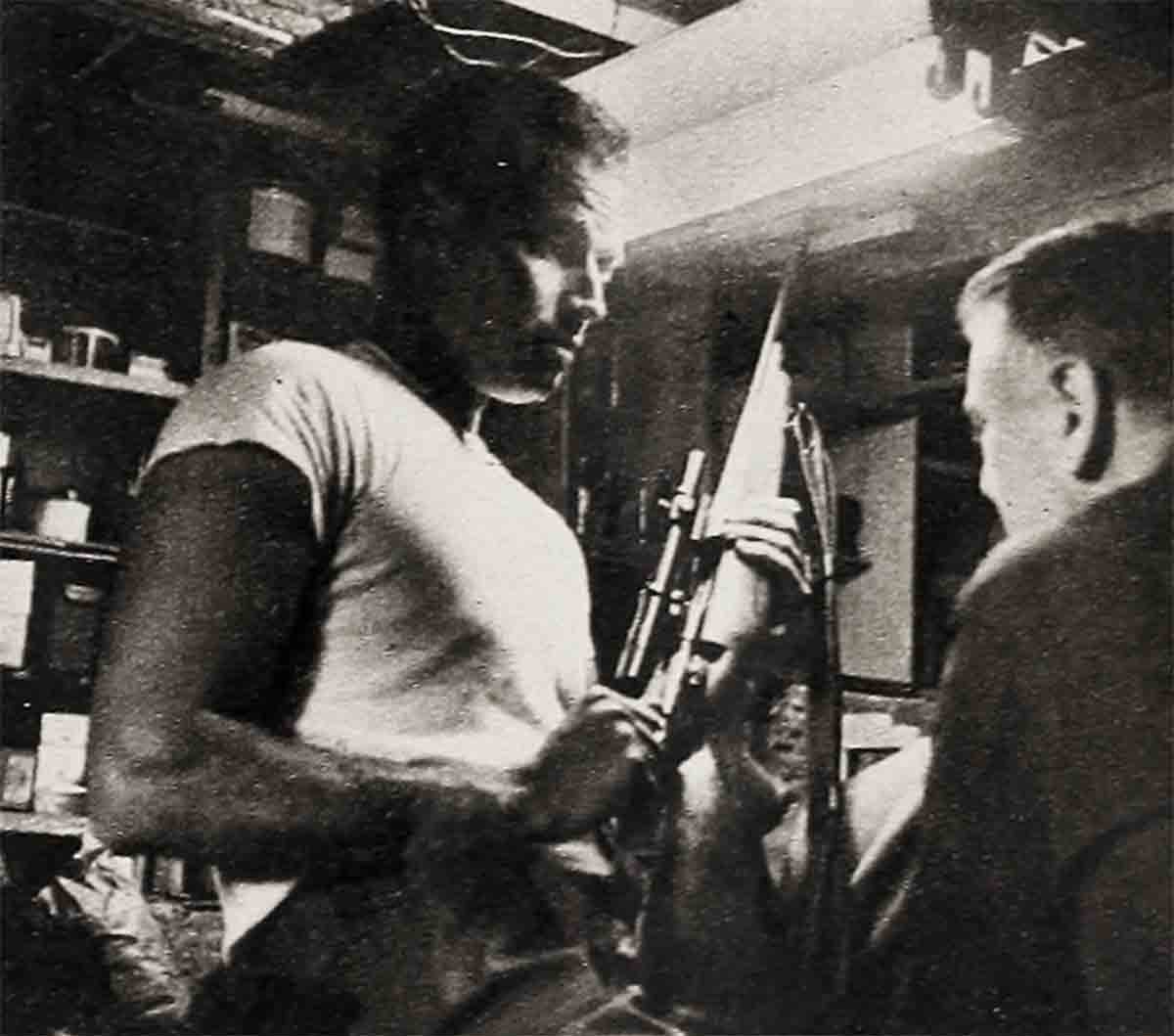

As a kid in this wilderness, Charlton (that’s his mother’s maiden name) had roamed happily around by himself, lugging a string of rusty traps, for muskrat and beaver. He tangled with scrappy bass on a bamboo pole, was trusted with a .22 almost as soon as he could go out alone. At eight, he’d been lost in the woods—no light matter, even for adults, in that country—but got home by himself, following a flight of ducks for direction.

But there weren’t many kids around to play with. About the only girl he ever knew was his little sister, Lilla. Chuck was a lone wolf, hunting his romance in adventure books, then going out to his woodsy hiding spots and pretending to be every character in the tattered volumes. “There’s no doubt in my mind,” Chuck says, “that my acting kick started in those days. I was acting all the time. I never did anything else.”

Once, spurred by an adventure tale, he wrapped up a book and an apple inside a shirt, tied it on a stick for bindle and set out to see the world. Way down the road, about dusk, his father met him, coming home from work.

“Where do you think you’re going, Son?” he inquired.

“I’m running away,” stated Chuck.

“Well, goodbye,” said his dad, passing calmly on. That wasn’t the way Chuck’s script was written. He had envisioned his parents in tragic tears. He turned, ran and caught up and was glad he had when the owls started to hoot.

Both Chuck and Lydia had won scholarships to Northwestern University. She wasn’t as lost in the clouds as Chuck, and Lydia Clarke arrived in Evanston a much smoother article all around. Undoubtedly, this accounts for her reaction to Chuck after she had given in to his awkward advances and granted a date. Lydia scribbled home to her mother: “I’ve just gone out with the most uncivilized, crude and rude, wildly untidy, impossible man on the campus!”

With that impression, naturally Charlton Heston’s first and only dream girl gave him a pretty hard time, or if you prefer Chuck’s description, she was “interestingly combative.” When he pestered this contrary cutie with reckless, absurd proposals she would yawn, “I’m just not interested in getting married.”

“Well,” he’d press, “if you ever did get married, do you think you’d be interested in marrying somebody like me?”

“Not possibly!” she’d dust him off, but in the end Chuck outhammed her.

At that time, he was running the night elevator in a swank North Shore apartment house, inhabited mainly by rich, retired tenants. You could tell just about when they’d go out and when they’d come in. There were long, idle hours when Chuck could stalk out of his cage and emote to the overstuffed furniture in the lobby. Sometimes a querulous guest would ring to ask if somebody was being murdered, but usually it worked out fine. At Christmas, too, there was a jackpot of tips which added up to the magnificent sum of $75 and gave Chuck his chance to make an impression on his reluctant lady love.

He took the $75, rented a swank suit of tails, top hat and boiled shirt. Then he called up Lydia at the campus cafeteria where she worked. She almost dropped a stack of plates when he invited her to do the town. “We’ll dress, of course, white tie and all that” she actually heard this untamed bumpkin declare.

They went to the Pump Room at the Ambassador East—Chicago’s finest—and even though they rolled down and back on the bus it was pretty high style. The awkward moment of the evening came when the captain steered the elegant revelers right past the table of a resident of his building who had unwittingly contributed a ten-dollar tip to this spree and was stunned speechless to see his elevator boy sweep by in full dress and wave a chummy “Hello!” Looking back, Lydia thinks it was then and there that she knew resistance to Chuck was no longer possible. But she didn’t let him know that, of course.

In fact, Charlton Heston was quite surprised when a telegram from Miss Lydia Clarke arrived. It stated rather primly and right out of the blue, “I have decided to accept your proposal.” Chuck had been canned from his hotel job, nut had been picked right up by the Army Air Corps and was in basic training at Greensboro, North Carolina. Lydia had spring vacation coming up. They were married on St. Patrick’s Day in Greensboro when Chuck promoted a pass from the sarge by pretending he was an Irishman. Being a pair of true artistes, they wandered around town until they spied just the right setting—a church with a white cherry tree blooming in front. They went in and even though it was almost six o’clock, they managed to do it up right.

So—you can see that romance and acting have been twisted together like sweet-peas on a trellis ever since Charlton Heston and his Lydia spotted each other—although usually the peas themselves have been in widely scattered pods. In fact, on Chuck’s brief leave the newlyweds took in a theatre performance—and the usher placed them in separate seats! “We should have known then how things were going to be,” Chuck grins. Pretty soon he found out for sure. In a matter of days, the groom was at Port Heiden, in the clammy Aleutians, hunched over a radio transmitter, and the bride was back at Northwestern.

When the conquering hero came back he had never looked better in his life. “He weighed 225 pounds,” remembers Lydia. “I thought, this is war?”

It was peace. And, of course, peace to Mister and Missus C. C. Heston meant launching a couple of green acting careers—a project guaranteed to reduce overstuffed figures. In the first year, Chuck regained his Lincolnesque look with no effort at all. He settled with his bride in a shabby furnished room in Chicago. They stored their food in a foot locker, cooked on a hot plate and washed dishes in the bathroom basin. The family budget for feasting was $6 a week.

In New York they lived m a railroad flat in rough, dockside, Hell’s Kitchen. It cost $30 a month and it meant sleeping on a bed Chuck had hammered. together from a few boards. The Hestons look back from these affluent years on those hungry ones with special tenderness. Until a few months ago, they sentimentally kept the Hell’s Kitchen flat as their eastern hangout. They would have it yet, if the city hadn’t condemned the building.

The reason is simple. They were together then. The clicking sound in their two careers was also the snapping of their poor, but permanent, home ties. Chuck, for instance, blew off alone to Boston for his first big break in The Leaf And The Bough. When Lydia’s turn came with Detective Story, it was back to Chicago for her, with most chances to see her husband coming via a TV set in her dressing room. Then there was Hollywood for one, New York for the other. Separation has been the price of their success.

“It would be silly to say we like it that way,” Chuck will tell you honestly. “But,” he asks just as earnestly, “what can we do?”

One thing the Hestons could do—if they were the types—would be settle down cozily in Hollywood and never move. Ever since The Greatest Show On Earth, Charlton Heston hasn’t had to beg for screen jobs. He’s the heroic toughie type who’s boxoffice bait as his jobs in The Savage, Pony Express, Ruby Gentry, The President’s Lady, Naked Jungle and others have proved. Lydia did perfectly all right, too, in Atomic City and Scalpel with Chuck. Both are tailor-made for Hollywood’s TV radio and the west coast stage stops which are multiplying season by season. Unfortunately, that’s not the antidote for their particular acting bugs—as virulent as ever, after all these years.

Chuck’s goal is to play Macbeth better than anybody has ever played it. Already, he has done some pretty terrific performances of it, the last being this summer in an ancient British fort hanging over the surf in Bermuda.

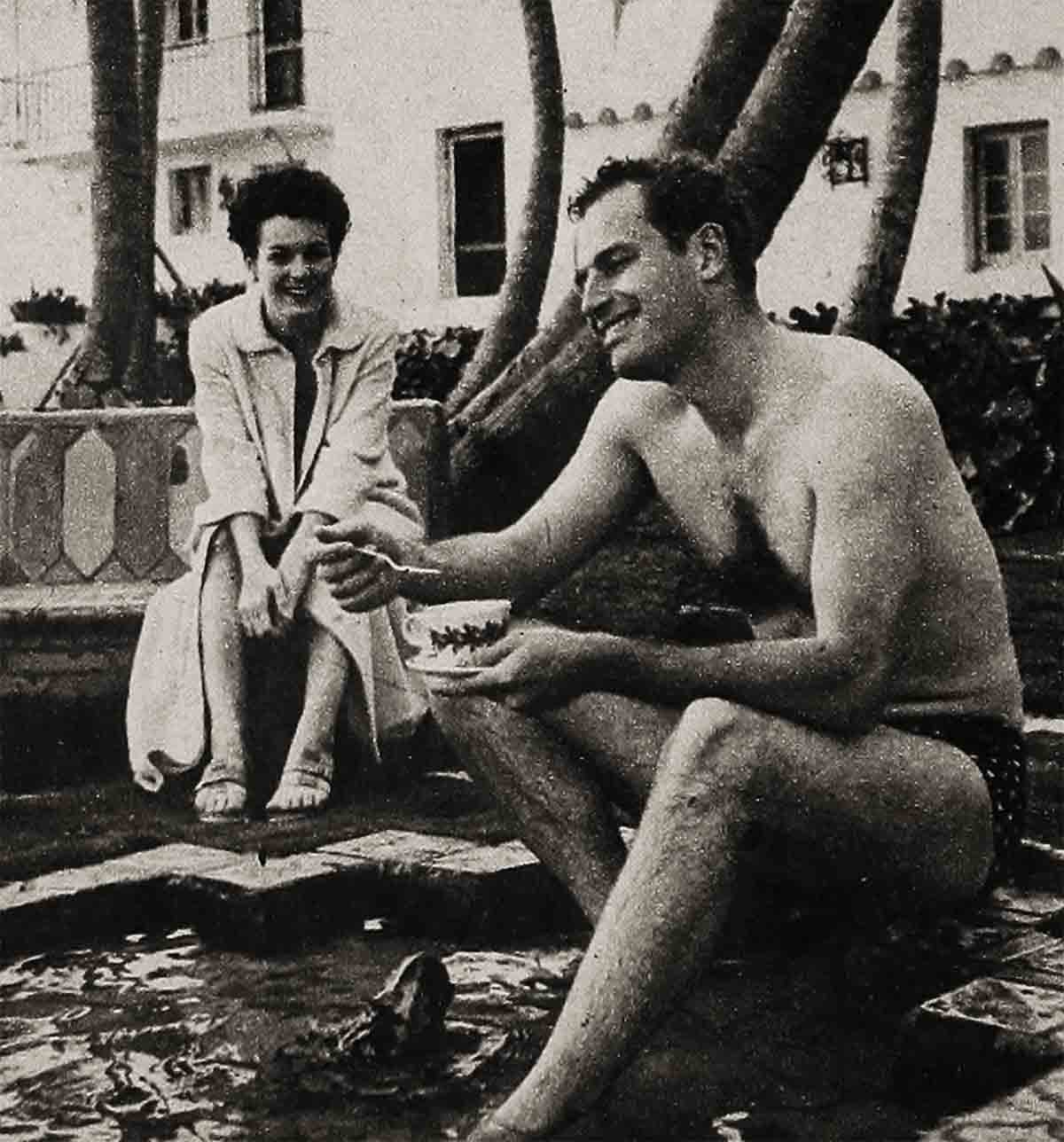

By now, Chuck and Lydia Heston are conditioned to settle down like tabby cats wherever they are. But anywhere at all Chuck is in levis or shorts and a T-shirt the minute he slings his bags to the floor.

Except for Charlton’s sketching kit, a couple of cameras and the necessities of a peripatetic existence, the Hestons travel light—and they almost live as light as they travel. Long ago, they learned that collecting plunder is just a headache when you’re hotfooting around. Luckily, neither is interested in rich trappings or fine feathers. It took Lydia years to talk her husband into investing in two suits. He had a collection of antique ties, hoarded since college days, and as rag-tag as kite tails, which she spirited to their incinerator, replacing the shabby lot with seventeen bright new ones. It almost caused a rift in the family. Probably the only other time Chuck got as riled at his wife was when he impulsively bought her an elegant mink stole as a surprise. But when she opened the fancy box Lydia popped his balloon. “Why, it’s a mink stole!” she exclaimed. “I don’t need a mink stole. Wherever would I wear one? Take it back.”

Both Chuck and Lydia are used to separation rumors and don’t get too upset, knowing what the score is with themselves and what they’re in for as movie celebrities. They know that as long as they keep hopping here and there, rift rumors are an occupational hazard. But the lack of a solid homelife, as the years tick by, worries them a lot more. For one thing, there’s the matter of a family. “Sure, we want kids,” Chuck will boom from under a wrinkled brow, “but not in a suitcase.” The only live dependent they’ve owned was their Great Dane, Caesar, whom they parked with Chuck’s dad as they rambled around. The big pup died when he was only four. “Ulcers,” explained the veterinarian. “Purely from loneliness for you two.” So thoughts of a family give them real pause.

In fact, the only way Chuck Heston has figured out to carry on the line is to revert to his rustic beginnings, hole in on the shores of Russell Lake and commute to Hollywood and all directions by rocket plane. The Michigan place is paid for. There’s plenty of wood for the fireplaces and the big eight-room lodge could take care of all comers.

“Snows are deep in the winter,” muses Charlton Heston at that pipe dream, “and we could just hibernate—like the bears. Lydia could have a baby every spring and I could grow a long beard like Father Abraham.” On him it might be becoming, but probably it will be a while before we see it. At twenty-nine, and with things going the way they are, that would be strictly a thought for the hustling Hestons’ future.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953