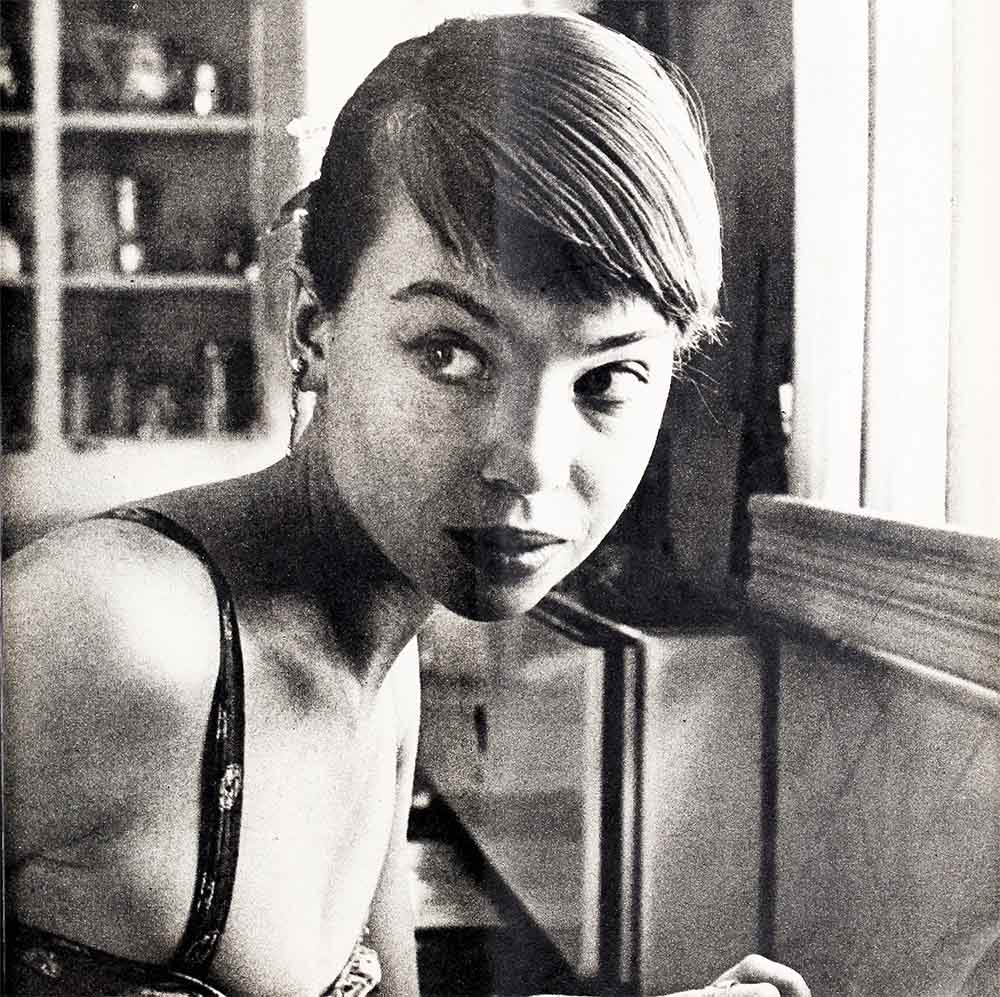

You Don’t Have To be Pretty To Be Popular

I have had many, many letters from girls who write to me saying that you are very worried because you are not the prettiest girl in your school, or at your work, or maybe in your particular town.

You are polite, you Americans, so you do not say that you write to me because I, too, am a plain girl. But I can read between the lines. Besides, it is true. I can practically hear you saying, in those letters, “How could a girl with your looks become a movie star?”

I will tell you this. I am more astonished to be a Hollywood personality than you can possibly imagine.

The other evening a magazine gave awards to me and Marilyn Monroe at the same time. I stood beside Marilyn, and looking up at her beauty, I thought, “What am I doing here—next to her?”

But I can say one thing in all sincerity to you girls who think you’re not pretty: To be plain need not be a handicap. In fact, it can be a help. It keeps you from expecting things to come to you too easily. It forces you to cultivate your taste, your brains, your personality. And, most important, it helps you to appreciate things when you do get them, and to have values that are true and lasting.

AUDIO BOOK

Let us be blunt: some of you are not pretty. The way your faces are put together there is not much chance—physically—of your ever being other than homely. Certainly you can not be beautiful—not feature by feature, that is. So what can you do?

Personally, I think the important thing is to cultivate your mind and cultivate your body. I think you must do both—and neither one at the expense of the other—each is a part of the whole, which is you.

When I was first in my teens, I used to ride back and forth in the Paris subway on my way to and from my ballet lessons. The year was 1944, and like all the other French people who were young, I had accepted the cruelties of war.

I mean, I thought the only way anyone lived was to be always hungry. You could never buy enough to eat. And you were always shabby, because in order to get anything new, you had to give up three old dresses, or coats, for one, and the new ones were made of such dreadful materials that they wore out almost immediately. You grew accustomed to being cold and uncomfortable. You even grew accustomed to the Germans.

But there was one thing I could not stand, when I was thirteen. If anyone looked at me, I was very embarrassed. I would turn my face quickly, so that no one would see me in profile. I would hold up my chin in a certain way that I felt concealed my protruding teeth a little better.

From the time I was a tiny girl, I hated everything about my appearance, and I was always trying to improve it. In France little girls can not get at cosmetics and they do not even have hair curlers and never, never permanents. So about the only thing I could hope to do that would better my looks was to chop my hair.

Even the color of my hair was uninteresting. It was absolutely straight and just hair-color, a sort of lightish brown. It still is that.

Each day my mother would say to me, “Leslie, promise me you will not chop away at your hair today,” and I would promise. But almost always the impulse was irresistible. I would pull up some locks somewhere, and snip, they were off! once I had braids on one side of my head, short locks on the other. Another time I let my bangs grow down to my eyebrows and my back hair to my waist. One day, when I was about ten, and the war had been going on for two years, I did up my hair on strips of paper, trying to make curls.

When I looked at myself in the mirror, I cried. I still do not like my hair curled. And I still can’t resist chopping bits off it.

I do not know whether it was the trials of war or her understanding of me that kept my mother from punishing me for this disobedience. She is very sympathetic, my mother. In her youth, she had been a dancer, but she never once urged me to it.

Of course, in war time, you can not look ahead. One is grateful, day to day, to be still alive. I did not think of my future. I was thin and short, and very anemic. But when I was eleven, I saw my first ballet, and then I knew what I wanted to do I begged my mother to let me take lessons, and she agreed.

I entered the ballet class and I saw the other girls’ eyes on me. They seemed to say, “Who wants this clown?” I was absolutely flat-chested, I had pipe-stem arms and legs, and my hair looked like a witch’s. Also, in terms of beginning ballet, I was old. Most of the other girls had been studying since they were five or six. But I wanted to dance, and I worked hard to catch up with the others.

Ballet is very strenuous. You really should be stuffed with beefsteaks all the time you are studying it. You should be warm, and you should have the right slippers. From the ages of eight to sixteen, I had none of these things. Yet I grew strong through the ballet. I began to understand grace. I began to know what it meant to move correctly, and therefore beautifully. I never became a prima ballerina—that is, the “star” of the particular company in which I worked. But I did advance to where I was a premiere danseuse—that is, I did individual solo dances, in which I could personally stand out.

Then, one night, when I was just fifteen, the miracle happened. I danced out from the wings, I did my solo and I heard the applause. I must have been better than usual that evening for the applause went on, and as I took my bows, I suddenly thought, “They like me. I am such an ugly duckling, but they still like me.”

I believe you girls who are plain can work this miracle for yourselves. You do not necessarily have to study ballet—though even a few months of it would help anyone under the age of twenty, I think. But you can certainly study ball-room dancing. I am very much for swimming, too. But I mean real swimming—not just once or twice across a twenty-foot pool or some such thing. I mean you should study swimming to the point where you can do a quarter of a mile at a time—and you should do some swimming or dancing daily. Or if you live in a community where you can only swim in summer, or where it’s difficult to find a place to swim at all, you can surely do some other sport. There are tennis, golf, fencing. Choose whichever you prefer—but do it daily, and try to keep on with it until you are tops, or nearly tops.

You will get more than grace from such physical training. Too many girls do not comprehend how attractive sheer vitality and strength are—for instance, as they are in Esther Williams. When I was in my early teens, I used to slump and be round-shouldered because my back was so weak I honestly couldn’t hold it straight.

As I took my ballet lessons, however, all my muscles strengthened and the more I worked, the more energy I had until today, when I am in training for a new ballet for a picture, I have so much energy that after twelve or sixteen hours of work, I can come home with enough left still bubbling in me to make me want to build a brick wall.

So please do not mope. Do not feel that life has been cruel to you in not giving you a face like a flower Stand up straight and see what you personally can do about yourself.

Where ballet is better even than sports, I think, is in the by-products it gives you. You learn good music. You learn decor. You learn make-up, and on stage, at least, you are dressed in a classic, beautiful way.

Personally, I took a very long time learning about off-stage dressing. In matters of chic, I was as I had been with my hair. I kept experimenting. In one way this was necessary. If I was to have any clothes at all, while I was growing up, they had to be old things of my grandmother’s, my mother’s or my father’s—yes, that’s right—my father’s, cut down. Some of them didn’t look much better than the frumpy things I wear in the beginning of my latest picture, “Lili.”

I kept right on being flat-chested till I was past sixteen. I had perfectly awful, scrawny shoulders, with bones at the ends of them that stuck up like wings. In France, all little girls know how to sew and I think it would be quite a good thing for many American girls to know, too, even though you do have so many charming ready-to-wear things.

I remember, when I was sixteen, I tried to make a dress for myself from an old suit of my father’s. It was very good tweed, and I thought it would make me look plump. And right where my bosoms should have been, I carefully put two pockets! How my family laughed when I came in wearing that outfit. My heart was broken then, my pride was seared, but now I know how good it was for me, for from that moment on, I began really studying fashions.

Eventually I learned what I believe is the first rule of attractive dressing: Forget about your bad points, and don’t waste your time disguising them. Instead, emphasize your good points. And, remember, the clothes themselves aren’t so important; it’s how you feel in them that counts.

My personal good fortune was that as I grew a little older—a vast seventeen, some of the older girls in the company (they were a shattering twenty-four and-five) took over my cultural education. I believe that “culture” isn’t a particularly fashionable word in American teen-age circles. If you don’t like the word, that’s all right. But what it stands for is terribly important, especially to you girls who aren’t going to get by on “flash.”

I believe there is a slang expression in this country that says if you are around money, some will rub off on you, or if you are around dirt, some of that rubs off, too. I would like to put in my own two cents’ worth by saying that if you are around beauty, that also rubs off on you. I am not remotely highbrow. I love jazz and driving in cars with the top down and drinking malts and concocting wild meals with my husband in our little house where the living room, dining-bar and kitchen are all in one.

Yet I know what I absorbed, in terms of beauty and understanding of living from studying good poetry, through visiting museums and absorbing paintings, sculpture, antiquities. I feel such beauty helps you know your own place in all of life. You feel surrounded by all the other dreams that men have had since the beginning of time. You aspire to better things. You dream. You, you believe, are sensitive. When you are surrounded by the art of the ages you see that other people, feeling such things, have mastered them. For me, this was a sure cure for loneliness, for weariness, for lack of food and money and pretty things.

But I was still shy. American girls grow up earlier than we do, date earlier, marry much earlier. In France, no nice girl “dates” before sixteen at the earliest and then she sees the boy in her own home, with her parents present. I had no dates in France, because, for one reason, our young boys were in the war. Then, I was only seventeen when I heard the amazing news that Gene Kelly was interested in me—for films in Hollywood!

I felt it could not be. I ran away and hid. Mr. Kelly was leaving Paris the very next day. No one could find me and I breathed safely when I knew he was gone. I felt I had saved myself a big humiliation.

But he remembered me and the next year, M-G-M in Paris sent for me. I said, ‘“But you can not want me. You would have to change me utterly.” They said, “We want you just as you are.” It was impossible—but what they said was true. They photographed me just as I was, my straight hair in its natural color, my mouth which is too big and my cheeks which are too round. And when they sent the test to Hollywood, Hollywood cabled that I was to rush overseas at once.

That was the second miracle that happened to me, and I came very humbly and shyly but very, very happily to Hollywood. I saw all the beautiful girls about me, but every one was very kind, and I forgot myself in the dances before the camera, and just tried to concentrate on projecting how very beautiful life itself can be.

My third miracle, you know, of course. My first date in all my life turned out to be with the man who is now my husband. I had gone to that date out of sheer loneliness, with two other girls from the ballet, and their dates. I was alone—and then Geordie Hormel, my Geordie, walked in. I spoke almost no English—but he spoke French. And from the very beginning we understood one another, in things that go deeper than words.

That is because we are similar people, Geordie and I, even despite our so dissimilar upbringings. We both love studying things. We both love simplicity, the simplicity, that is, which means books, and music, and amusing people who are young in spirit, rather than the pretentious folk of any age.

I hear you thinking, some of you readers, what more can a girl want? I agree with you. There isn’t any more I could want, except, soon, our children.

And behind it all, I have, as I look at my funny face in the mirror, one reassurance. It is the same one that every plain girl has, that the beautiful girl never has. You know you are loved for yourself, for the personality that in my case is named Leslie Caron, and in your case is named Mary Smith, or Helen Jones, or Betty Brown—the individual you, the unique you, which God sent into this world.

In turn, you love the man who falls in love with you, even more, perhaps, than a beauty could—because you know he wasn’t caught by any surface glitter, any superficial thing that you can’t possibly maintain as the years go by. No, he will have been won by the things that you can develop and deepen in your character, that can make your life richer and richer as time goes on.

This is the gift life presents to us girls who didn’t get the Grecian noses, the slumberous eyes, the flawless lips. Personally I am deeply thankful for it.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1953

AUDIO BOOK