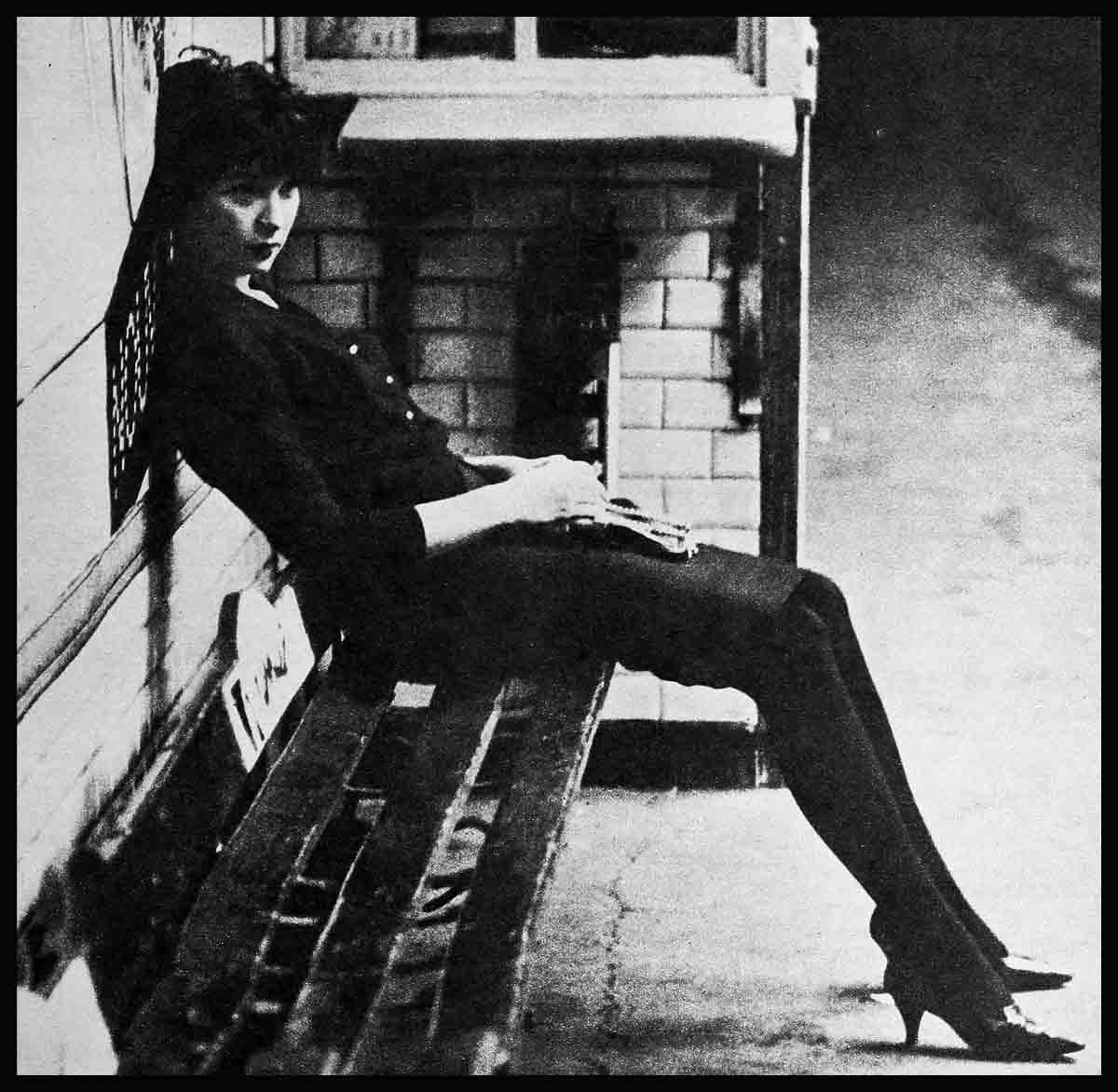

“Why I Lived With The French Streetwalkers?”—Shirley MacLaine

Actresses come in two breeds. There are those who are content to live in their little Hollywood niche and never wander out. The performances they give are not based on first-hand knowledge but on a director’s know-how. The other breed consists of actresses who have to “see” for themselves. They want to devour every aspect of life to add new dimensions to their talent. Shirley MacLaine is this kind of actress. Here, in her own words, is one of the most exciting stories we have ever printed in Photoplay . . .

this year, I went to Paris to do a lot of research on French streetwalkers. In Les Halles (a section of Paris), I studied them, talked to them and even lived with them for four nights in a small hotel. I did it because I had to know how they think. Sure, I know what their job entails, but there were many things I didn’t know—like how much money they get. But most of all, I wanted to ask them this question: “How do nice girls like you get into a racket like this in the first place?” Well, I asked them and the question was a bit too cerebral for them—in fact, most questions were a bit too cerebral for them. They’d just look at me and say, “Oh, it’s a good job” or “Oh, it pays good money” or “Oh, we get a lot of sleep!” and things like that. But being there and actually seeing it—that’s what I had to do. Even though I’d read books about streetwalkers, reading wasn’t enough. I wasn’t going to be satisfied until I actually saw them in action.

Why did I want to do this? Well, it’s not because I’m just some kind of a nut! I did it because I was going to play a French streetwalker in “Irma La Douce.” And I felt I could not play the part unless I lived with them. I would have felt like an idiot just standing on the street with a slit up my skirt and twirling a handbag, and asking the first man who walked down the street if he’s got any time. Because that’s exactly what happens in the picture. And now that I’ve actually seen them, I know they stand three or four feet apart, and each woman has her own little piece of sidewalk. I know that the man who keeps her is her protector, and he gets all the money she makes and keeps her in clothes, food and a place to live. It’s an interesting little jungle down there. I’ll tell you that. And Mr. Dunn and Mr. Wilder’s script for “Irma” is very true to life. The way it happens in the movie is exactly the way it is in real life. I know that now!

I found that every one of the girls had fallen in love with a guy who was in that business already. And, after maybe a year or so, the man would suggest to her that they need a little more money to live on and so forth, and he suggests this type of business. He has. her meet some other woman who is in it, or an older woman with experience; then he sets her up in the business, and she’s on her way. And because she’s so much in love with this man she’ll do almost anything to hold him. That’s really the basic reason why these girls became streetwalkers.

It also involves areas that have nothing to do with sex. It’s how they grew up as children, and the fact that they were lost, and most of them have IQs of about twelve. These girls have a very strange moral code. All of the girls wear crosses around their necks—they’re very strict in some areas. Religion is one. And brother, when they get married, they get married, and that’s all there is to it. This business of a prostitute being the best wife in the world—there’s a great deal of truth in it. Matrimony to them is holy; absolutely.

My marriage

Now, where this particular marriage of mine is concerned—I think being together with someone you love is the most important thing in the world. But I think everything has to be tempered and done with moderation; there’s a great deal of truth in that. My husband Steve’s business keeps him in the Orient, and I’m there with him about seventy-five per cent of the year. Two weeks of the time we’ll be apart, and for a month at a time we’ll be together, then we’ll be apart for three weeks and so on. When we’re apart it is for a reason; either I’m working or he has to go somewhere.

This apartness isn’t something we planned, it’s something that just evolved. I know we’ve been the subject of a great deal of gossip and conversation and so forth. But I think it’s obvious that our marriage has succeeded very well.

I see too many marriages around me where the people are together so darned much that they couldn’t care less about one another—really—and boredom sets in, all the enthusiasm disappears, and they can’t look at their partner in any kind of rosy light. It’s more like a ball-and-chain—something done out of necessity. I don’t know, it’s as if marriage guarantees that each one owns the other. Well, what is that? I think that will disintegrate two people quicker than anything.

This business of being together all the time, every day, every night—my goodness, how can you look at the two of you objectively if you don’t compare it to something on the outside? And brother. I’ve had a long time to look around; and I wouldn’t change twenty minutes with Steve for a lifetime with anybody else.

I think outside influences have as much to do with an adult’s progression as with a child’s progression. And I certainly don’t want to limit our daughter, Sachiko (Sachi for short), to the confines of her mother and father. I also think it’s very important for a child and each individual member of a family to have his own individuality protected all the time. And that’s when the whole unit can be successful. If each person consistently blends into the other to such an extent that they don’t have any privacy, they also don’t have any feeling of individuality. When this happens, the whole family suffers.

I’m on a picture usually eight or ten weeks, and when I come here to the States I kind of feel I’m on location; sometimes, once or twice during the picture. I’ll fly home to Steve and Sachi—have a Monday off, or something. The rest of the time I’m always with her, usually in Japan.

But last summer the three of us drove all over Europe. I went to Russia first and Steve and Sachi came from Tokyo, because Sachi goes to school in Tokyo. And we picked up a car and drove through Switzerland, Germany, France and Italy. We had a wonderful time. After two days in every country we went to. Sachi was speaking the language. She has been going to school in a foreign country since she was about two years old, so her ear is attuned to the foreign sound. I think mat’s what it is. She has a very accurate ear for languages, anyway. And she’s just used to speaking something other than what she grew up with. She speaks fluent Japanese, Siamese, Cantonese, Chinese, Burmese—oh yes—and a little English.

Home is where we are

Travel is one of the best educations a child can have. Of course, when she travels, either I’m with her or Steve is with her. And we have a house in Tokyo and one here in Hollywood, and a little place in Hong Kong. So I don’t know what you would call home, except wherever we happen to be.

In Tokyo, Sachi goes to the Nitchi-Natchi School—which is run by Ambassador Reichauer’s sister. It’s an international school—its students come from all over the world. They are taught in about four languages—a different language every day. Sachi can read and write in every one of these languages. She’s learning to ride, too. She’s swimming, skiing, ice skating and carrying on. She doesn’t really miss California or anything when she’s away from it. Whenever she goes anywhere, she goes to something, not away from something; and she looks with great enthusiasm and interest at what she’s going to see i next. Steve traveled a lot when he was a child—he grew up traveling—so I suppose it rubs off on me and on Sachi. But he always had a great affinity for the Far East, particularly Japan. He read and wrote Japanese before the war, and served there during the war. He was one of the first troops into Hiroshima. That’s how, as a matter of fact, Sachi got her name. There was a little girl in that destroyed city who had no father, no mother, no sisters or brothers. She didn’t even know her name, but Steve called her Sachiko, because she was always smiling. And he put through adoption papers to bring her back to the States. And just before they were finalized, she died of radiation sickness. And he always said that if he ever had a little girl, he’d like to call her Sachiko.

East vs. West

As far as the Far East is concerned the most exciting thing is that after hundreds of years, it’s come out of its cocoon. It’s now beginning to feel its oats. The success of modernization in Japan has started the ball rolling. I’ll go back to Japan after having been away for three months and the changes are amazing. I love living there, I love being a part of something that’s vital and growing.

And yet, in spite of this constant change, the Japanese seem to have found the answer to being at peace with one-self. Maybe it’s because they’re so crowded—ninety-nine million people living in a country half the size of California, and one-half of the land is uninhabitable because of the mountains. And maybe this kind of forced, cramped condition has made them develop some kind of attitude so that they don’t fight. And they don’t! They don’t even argue with one another. This business of famous Oriental politeness has come from necessity, aside from being something pleasurable. At least, that’s what I think. I think we have a lot to learn from them. They won’t, for instance, let tempers flare. We don’t like it because we can never tell where we stand with one another unless tempers do flare.

I rather like the business of getting along; but I also like to have my feelings felt, and I like to know where I stand, too. So I just sort of blend into the two environments.

There are many things that happen in life—things that change from one day to the next. That’s half of being alive—each day something new—so you adjust your ideas and your opinions and outlooks. You can’t say you’ve figured life out and that you’re going to stick to your plan the rest of your life. You have to keep altering with the times, with experiences, with conditions. And that’s what I try my best to do. But when I know that I love somebody, that remains constant. How I love them, the way I adjust my love—that’s what’s flexible—not the love. You have to do this or you’ll get lost in the shuffle.

AS TOLD TO FRED ROBBINS

Shirley stars in “Irma La Douce,” UA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963