My Bosses Are Out Of This World!—Nancy Lowe

An exclusive interview with twenty-one-year-old, Nancy Caryl Lowe, secretary to seven great men—America’s astronauts!

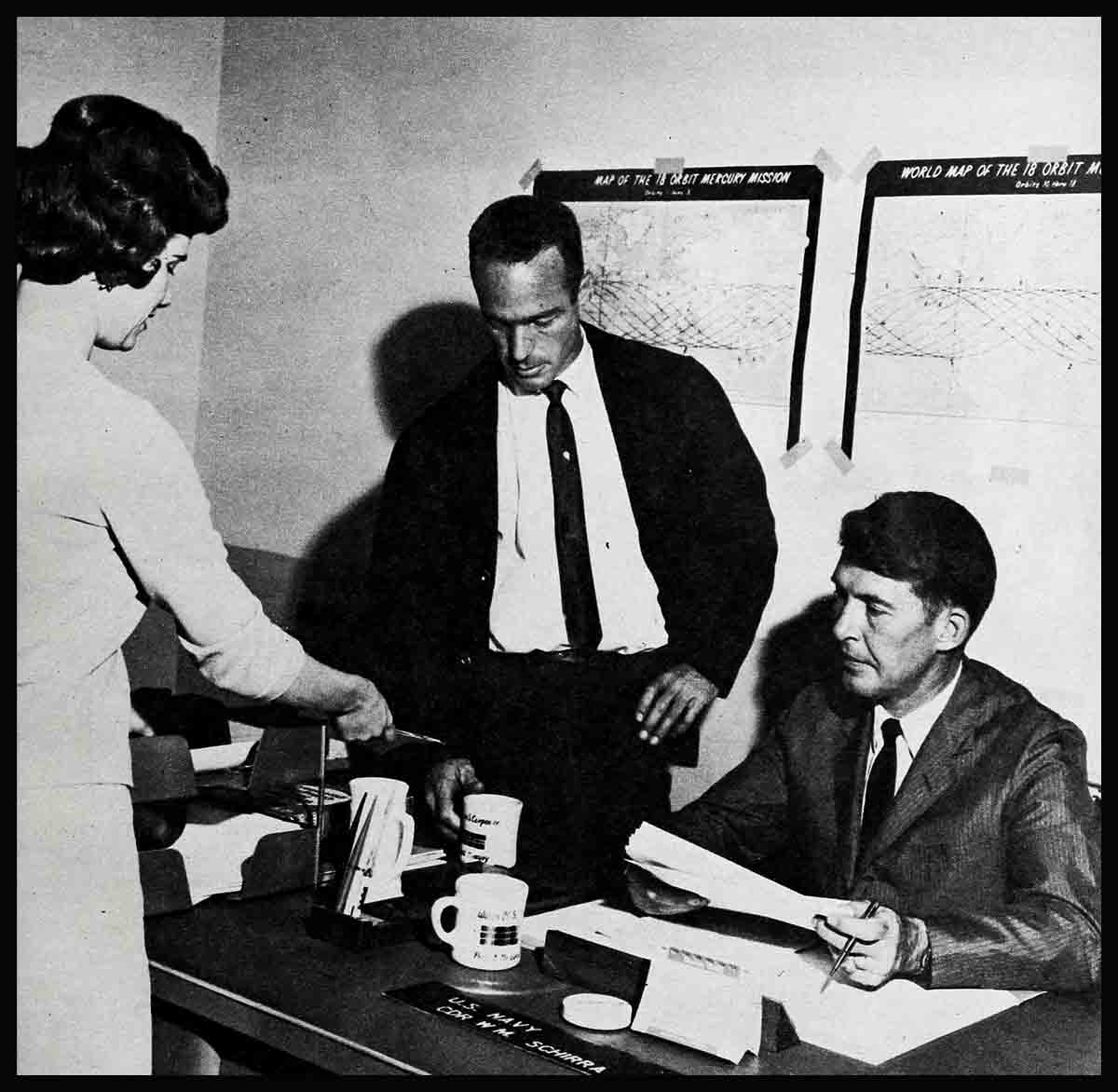

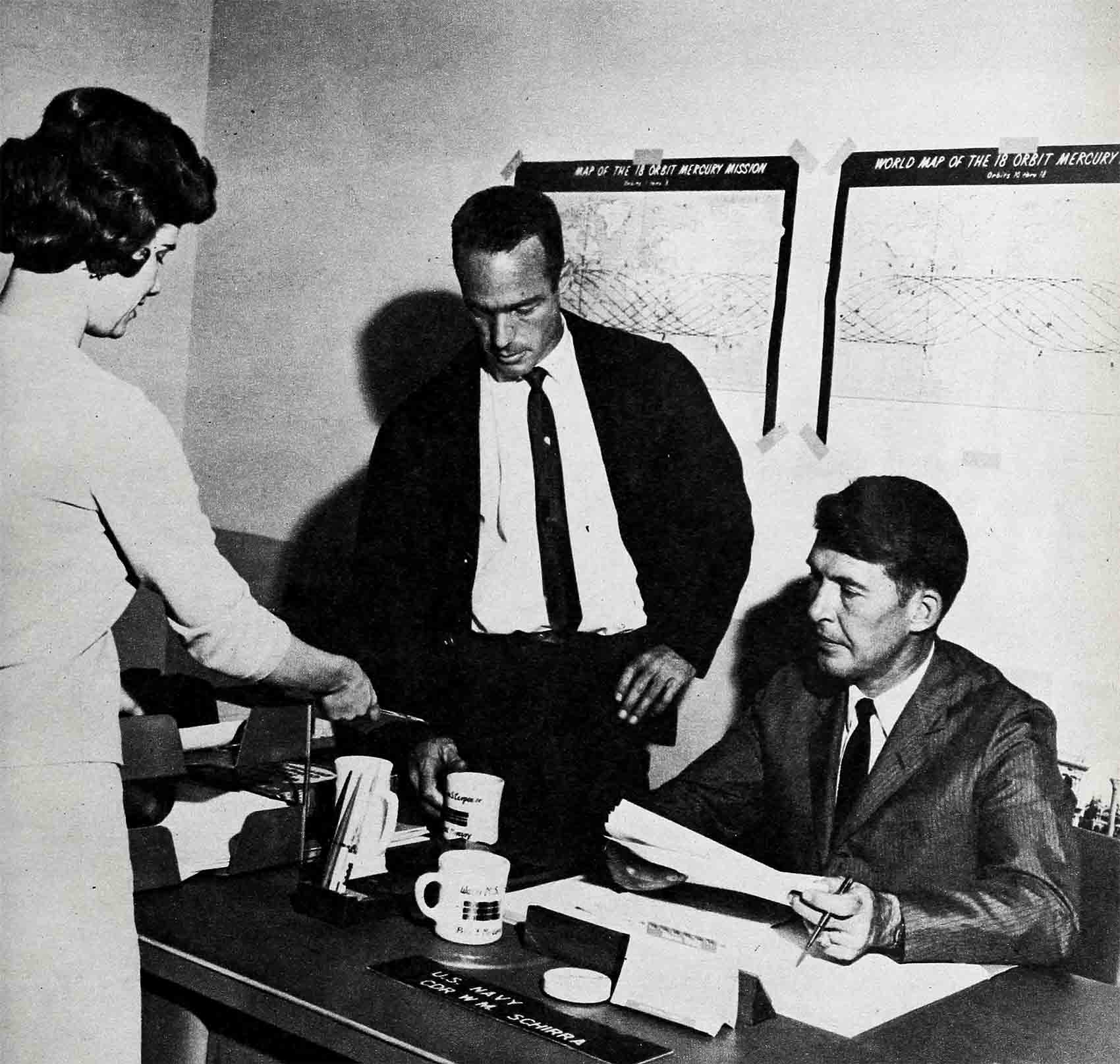

Place of interview: Room 203 of Building 60—Space Agency (NASA) headquarters, Langley Field, Va. This is Nancy’s office. One desk. Two phones. Three locked file cabinets. Battered air-conditioner. On Nancy’s desk, a jar of candy balls. Also a kooky figurine of a man from outer space—Martian style. Also a coffee jug, a gift from the astronauts, inscribed: “To Nancy Lowe, our friend and secretary ‘par-excellent,’ with best wishes and many thanks.” A secretary’s personal, very special treasures.

One door away is the entrance to the astronauts’ office. Surprisingly small. Cramped, in fact. Seven desks. One phone. Two battered air-conditioners. Twenty-four hour clock on the wall. Blackboard. Two maps. Eight windows. Each desk piled with papers. Each desk featuring at least one personal effect. On Carpenter’s desk, a globe—a gift from his wife. On Glenn’s, a jug inscribed: “I work well under pressure.” On Shepard’s, a tiny toy tiger. On Grissom’s, a sign reading: “If you wanna race—go to Daytona.” On Cooper’s, a big cup with a drawing of a sad-eyed dog and the inscription: “Coffee Hound.” On Schirra’s, a white jug marked: “Wally.” On Slayton’s, an ashtray inscribed: “May your birthdays bring you more horse power and less exhaust.” But back now to the story, which this reporter took down so painstakingly that Nancy offered help. “Would you like me to take it in shorthand while I’m talking?” she asked. But her kind offer wasn’t really needed—here is her story of life with America’s seven astronauts—word for word:

“Like most secretaries, my working day begins at the coffee pot. See it over there? It holds twenty-four cups. When the boys are all here, I usually make at least two pots a day.

“I get here a few minutes before nine every morning. Then they come in, one by one—Col. Glenn by air shuttle from Washington; Comdr. Shepard from his home in Virginia Beach; Maj. Cooper and Comdr. Carpenter from their homes here on the base; Maj. Slayton and Comdr. Schirra and Capt. Grissom from the nearby housing project where they live. One by one they come up that staircase outside in the hallway there. I can tell who it is just by their footsteps.

“I can always tell when Comdr. Shepard is here, even before footsteps—just by the way he parks his Corvette down in the drive below. Whoosh . . . stop . . . and here’s Comdr. Shepard. And one by one they walk into the office and say, ‘Hi, Nancy,’ and I always say, ‘Good morning, want some coffee?’ And our day begins. Very relaxed. Next to coffee, my bosses like their soda-pop best. We play a game called Queen Bee every afternoon—for soda. You flip a coin until one person becomes Queen Bee. After that, everyone who loses a flip has to pay the Queen Bee a quarter, and the Queen Bee buys the soda—but also makes a nice little profit on the side. The day I lost, after a winning streak for two weeks, Comdr. Shepard grinned and said, ‘Nancy lost! Let’s have a holiday—let’s give her the rest of the day off!’

“It was just a few minutes before five o’clock, so I just grinned and said, ‘Thank you very much, Sir, but I think I’ll stick around for the rest of the afternoon.’

“That Comdr. Shepard. He’s really a tease. In fact, they all like to tease me, my bosses—tease me something awful. About just everything you could mention.

“For instance—I’m always saying things that are misconstrued. I’ll just be talking along like this—and say something perfectly innocent. And then I suddenly see seven pairs of eyes with great big gleams in them and I say to myself, “Oh oh, Nancy, you’ve done it again.” They never explain to me, of course, what silly thing I’ve come out with this time. But I can imagine. . . .

“And they tease because I love to twist. I just happen to love that crazy dance. It all started down at the Cape (Canaveral) a few months ago. Before that, I kept my twisting to myself. I’d do it at home in front of the mirror, practicing away for hours. Or I’d be helping my mother set the table and I’d be twisting.

“But I never thought I’d do it in public. Not until that night at the Cape. But there we were, a few people and myself, and the M.C. at this place in Cocoa Beach—they call it the Peppermint Cane Lounge down there—announced a twist contest.

“Well, a fellow I knew came over and asked if I’d join in with him. I don’t know why, but I found myself saying yes. And I don’t know how—but the two of us ended up winning and were unofficially crowned Cocoa Beach’s King and Queen of Twist.

“Well, can you imagine the comments I’ve been getting from my bosses since that night? They’re really lulus . . . what’s that? Have I ever twisted with any of my bosses? . . . (Laughing) Sir, I’d rather not answer that question. I like my job much too much to answer a question like that.

“But—tease, you say?

“Well, for a while there. Col. Glenn had this tease with me about oysters. It all started this one day when the boys invited me to have lunch with them. We went to their mess and as we approached the counter I heard one of them say, very happily, ‘Oh boy, oyster soup today.’ I nearly froze. I’d tried oysters once and I hadn’t liked them at all. My first reaction this day was to decline the soup. But then again, I thought that would be downright impolite. So I looked and I looked and I picked the bowl with what I thought were the fewest oysters in it. When we got to the table, though, I just couldn’t eat it. I kept making all kinds of little excuses to keep from picking up my spoon.

“Finally, Col. Glenn caught on. He said ‘Go ahead, Nancy, eat it—it’s no good when it’s cold.’ I admitted then and there that the truth of the matter was that I just couldn’t abide oysters; that I liked the broth, but I just couldn’t abide those slippery little things. ‘Well,’ Col. Glenn said, ‘in that case, let’s have a conference.’

“The upshot of our conference was that the Colonel took all oysters and gave me part of his broth in return. That was nice enough of him, I thought. Very nice. But Col. Glenn wasn’t going to let it go at that. Oh no. For a few days after that, everytime I saw him, he’d stop me and reach into his pocket and say, ‘Would you like an oyster, Nancy?’ I knew he was only kidding, of course, but there was just something about the word that didn’t sit well with my stomach. And I don’t have to tell you that Col. Glenn stopped the joke when he saw my face turning pale.

“About teasing—did I tell you how I got my nickname? Well, right after Comdr. Shepard’s flight, I appeared on the TV show, ‘To Tell the Truth.’ I stood on the platform with two other girls—one was really a more mature-looking woman—and we all said, ‘My name is Nancy Lowe.’ And then Bud Collyer, the M.C., explained that one of us was secretary to the seven astronauts. Well, all but one of the panel members guessed it was me. But the one who didn’t, she said, pointing to the matronly-looking woman, ‘I think she’s the one. I think those boys would need to work with the more motherly type!’

“Need I say more? As soon as I got back to the base here, it was ‘Little Mother, would you get me this?’ and ‘Little Mother, would you take a letter?’ Little Mother. That sure was me for a while. Little Mother to the seven astronauts.

“I have eight bosses”

“What’s that? You get the impression that all we do is have a ball here? Well let me say—there’s a lot of work goes on in this office, too.

“The boys—well, the whole world knows what they do.

“My job? Actually, it’s not much different than what most secretaries do—except that I have eight more bosses than most girls. The seven astronauts and Dr. (William K.) Douglas, their physician.

“I would say that my main job is taking dictation. And I answer correspondence. Not all of it, mind you. There’s so much coming in since Col. Glenn’s flight that we couldn’t possibly answer it all. Just yesterday we sent 1,500 pounds of mail—all for the Colonel—to Washington. The usual crackpot letters—you know—‘You have no business venturing into outer space, young man.’ But most were the praising kind, and from school children working on class papers. They just need some personal information from the Colonel to make their papers complete. And oh, those requests for autographed pictures of Col. Glenn.

“I’ve started to get some mail, too. Personal. For me. From people all over the country. Some of it is quite uncomplimentary. For instance, I was on ‘What’s My Line’ a few weeks ago, and at one point John Daly called me the ‘Twist Queen of Cocoa Beach.’ A few days later I got a letter from this woman saying, ‘Aren’t you ashamed of yourself—doing that awful dance in public?’ And I got one from the president of a ladies’ garment company who said he had seen the show and was sending me a complimentary pair of twist panties. These I’ve got to see! Also, of course, I get a lot of letters—from girls mostly—asking me which astronaut do I consider the best-looking, which has the best sense of humor, and so on. These I answer by saying that I think they’re all wonderfully humorous and good-looking, which is an easy out but also happens to be the truth.

“Like most secretaries, I occasionally shop for my bosses when they’re too busy—you know, presents for their families. . . . But right now I’m mostly readying things for our move. That’s when the whole NASA operation here at Langley switches to Houston, Tex. It’s quite a job.

“Genuine career girls . . .”

“I’m very excited about it. Aside from the three trips I’ve made to Cape Canaveral and the two to New York, this is really the first time I’ll be leaving home for any length of time. Of course, there’s sadness in my heart about all this, too. Because I know I’m going to miss my family very much. Very, very much.

“I come from a big family. There’s my father—Hansel Lowe: he’s a heavy equipment inspector for the government at Fort Monroe. There’s my mother—Nellie Lowe; she’s a full-time housewife, or more than full-time—since she has borne and brought up six children. In order of birth there’s my brother Wayne—he’s twenty-four and in the Navy now. submarine service. There’s me. My brother Philip is nineteen. My sister Cynthia is fifteen. Donna is eight. And that Debbie—she’s five—and she runs the whole house.

“Actually, I don’t talk too much about my job at home. I try to treat it as a typical job—you know, keep things pretty normal. Summer weekends I go swimming a lot. In the winter I go bowling. Or watch TV. I just think ‘Dr. Kildare’ is fine. Or I go to the movies. I like good pictures. And I like anything at all with Charlton Heston. Or with Robert Mitchum—though you don’t see much of him these days, do you? With Rock Hudson—I guess I’m a typical female in this sense. And with—what’s his name—that black-haired fellow who was in ‘Home From the Hill.’ George Hamilton! Also, I like to play basketball. I love to read books by Frank Yerby and Frank Slaughter. And I guess more than anything—since as a secretary I hate to write personal letters—I spend an awful lot of my home time on the phone talking to my best friend, Lyn Holloway.

“So you see, I try to live a real normal life. But my excitement about the job, much as I try not to show it, must just glow all over the place.

“The most exciting moments of my job?

“That’s easy—being at Cape Canaveral for the three flights so far. Comdr. Shepard’s, Capt. Grissom’s and Col. Glenn’s.

“I don’t mind telling you I was a nervous wreck for Comdr. Shepard’s flight. I’m not one who likes to show her emotions to others, so for this flight I stayed alone in crew headquarters. Everyone else was outside at the press site. But I just stayed alone in that office, watching the beginning of the flight from the window—half leaning out, half falling out. Then I turned on a TV set in the room and watched just like everyone else in the country.

“My bride . . . my roommate”

“For Col. Glenn’s flight—well, I was only less nervous because he was so calm. Right from the beginning, the day he walked in from the conference room with a smile on his face and said, ‘Nancy, I’d like you to place a call to my bride.’ He never refers to her as ‘Annie,’ or ‘my wife.’ Always ‘my bride,’ or ‘my roommate.’ He said to me, ‘It looks like I’m not going to be home for a while and I want her to know.’

“I said to him, ‘You got it. Colonel?’

“And he said, ‘Yes. I’m supposed to go to the Cape in two weeks.’

“As it turned out, I went along. And I’ll never forget those weeks of waiting with Col. Glenn, working with him. The tension, the postponed flights—it was enough to wear anybody to a frazzle. Some of the reporters who were there covering the flight were absolutely biting their fingernails. But Col. Glenn remained the calmest man in the whole wide world. And after a while I lost whatever nervousness or jitters I had . . . just by being close to him.

“When he wasn’t in the Briefing Room he’d spend a lot of time with me taking care of his mail. It’s funny with the Colonel, you know? He’s a man of so many different and fantastic experiences that he’d be dictating a letter and in the middle of it he’d be reminded of something, and he’d say, ‘Nancy, did I ever tell you about—?’ And then it could be the war he’d talk about. Or college. Or test pilot school. Or about himself and Annie when they were very small, and when he started to court her. Oh, I wish you could p hear the love in his voice whenever he talks about his wife and his children. It’s just the loveliest thing to hear.

“As I said, he wrote lots of letters to personal friends during this period before his flight. A few, to his very best friends, he would sign, ‘Pierre Glutz’—which I thought was very funny. . . . He also answered people who had written to him—especially children. He is the kind of man who goes out of his way for everybody. For me, for instance.

“I’d like to give you just two examples of Col. Glenn’s kindness to me, if I may. One was that great day after his flight, when he returned to the Cape and was greeted by President Kennedy. Well, Sir, that day I was just one of thousands of people at the airport. All I wanted was a look at my boss, to see for myself that he was really all right. I got near the speakers’ platform.

“The car with President Kennedy and the Colonel drove from the plane to the speakers’ platform—and stopped right in front of the spot where I was standing. And Col. Glenn was saying something to the President. . . . All of a sudden he saw me. He smiled, put up both of his thumbs and shouted, ‘We made it. Nancy. We made it.’

“I shouted back to him, ‘Welcome home. Pierre Glutz.’

“He said. ‘It’s good to be back.’

“A few seconds later Col. Glenn and the President got out of the car. He took the President’s arm and led him over to where I was standing. He introduced me to President Kennedy. And then, right in front of the President,he kissed me. Right here. On this cheek.

“Again he said, ‘We made it, Nancy.’

“And—I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t. I might’ve burst into tears right there.

“Another time I’ll never, never forget, as long as I live. … It was a Wednesday night, about a week later. I was back here in Virginia and planning how the next day I would watch the great New York City welcome parade for the Colonel on a TV set. All of a sudden, there was a boy at the front door with a telegram for me. It read: ‘DEAR NANCY . . . I NOTICE THAT THROUGH AN OVERSIGHT YOUR NAME WAS LEFT OFF THE INVITATION LIST FOR TOMORROW’S PARADE AND RECEPTION IN NEW YORK. I WOULD THEREFORE PERSONALLY LIKE TO INVITE YOU.

COLONEL JOHN H. GLENN, JR.’

“Well, it would be silly for me to even try to describe the thrill I got from that telegram. Or the thrill I got the next day flying to New York with everyone else and taking part in that fantastic parade.

“Can this be me?”

“But all the time I kept thinking—this can’t be me, Nancy Lowe, a secretary from Poquoson, Va., population 4,000—a fishing village with a couple of banks, a few stores, one movie theater . . . it cant be me sitting here in this car, in this parade, a part of all this excitement. It can’t be.

“I thought back to how I’d gotten my job. I’d graduated from Poquoson High in June, 1958—third in my class, there was the Valedictorian, the Salutatorian—and me—the Third-atorian. I’d taken a month’s vacation after graduation and gone to Fredericksburg to visit some relatives. When I got home there was a notice from the personnel office at Langley Field, asking me to come for an interview.

“Long before that, I’d decided to take the first job anyone offered me. I’d spent enough time lazying around and I sure wanted some money for new clothes. So I went for the interview, was accepted for the job and placed in a steno pool for a whole bunch of engineers.

“That’s how it began. And then there were all those rumors about a space program—with strange words and phrases like ‘astronaut’ and ‘project Mercury’ bandied all over the place. . . . Then before I knew what was happening, I was transferred to the medical division, to Dr. Douglas’ office. And slowly I began to realize that I was becoming more and more involved with this space program.

“The selections were announced on April 6, 1959. And a few days later, just before the men arrived here at Langley, I’d been more or less told that I was going to be their secretary. Secretary to the seven astronauts!

“They arrived, all seven of them, late that afternoon. I was introduced, we all shook hands and said our hellos. Downstairs, later, some of the girls asked, “What are they like? What are they like?’

“And I said, as near as I remember: ‘To tell you the truth, they’re quite ordinary. They’re nice-looking and healthy-looking—but they don’t have two heads, if that’s what you mean.’

“It didn’t take me too long, after that, to realize that my bosses weren’t ordinary at all. They might not have two heads, but they certainly had hearts and senses of humor and streaks of bravery that were ten times—a hundred times—larger than most people’s.

“And now here I was, riding in a big open car in New York City, in Col. Glenn’s triumphant parade. Waving to the people. Laughing a little. Crying a little. Remembering. All at the same time.

“And I thought to myself, ‘Nancy—you’re the luckiest girl in the world, in case you didn’t know. . . .’

“I thought, too, that day in New York, how different things might have been for me if I hadn’t made a certain important decision once. You see, all during high school I had gone steady with a boy. A nice boy. And like practically everybody else in high school who went steady at the time, we planned to get married.

“But about graduation time, for some reason, I thought it best if we didn’t get married. I don’t know why exactly. Maybe I figured we were just too young—and there was more to life than marrying in your teens and being just like most everybody else.

“So I spoke to this boy. He said he understood. We called off our engagement. And a few months later I answered that note from the personnel office at Langley. And all this began. . . .

“You know?—a couple of days ago a friend of my mother’s said to her, ‘Nellie, tell me—Nancy is nearing twenty-two now. When does she plan to get herself a husband and married?’

“My mother said, ‘Nancy will be married someday. She’ll be a good wife to someone. She loves children—and she’ll be a good mother. But for now, I’m afraid she’s just married to her job.’

. . . (Smiling) “And do you know what? I’m afraid my mother is right.”

THE END

—BY ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1962