Max Schell Wasn’t Schnell Enough For Nancy Kwan!

THE WORLD OF “Suzie Wong” came crashing down recently when Hollywood’s yummiest Yum-Yum girl fell in and out of love.

Ali Nancy Kwan did was get married.

But that was enough to give her bosses ulcers, make monkeys out of her press agents, anger the gossip peddlers and surprise the HELL out of Maximilian Sc——.

“Why is everybody so excited?” the Eurasian beauty inquired as shock waves set off by her London marriage rolled around the world to Hollywood and Hong Kong.

“Everybody said I would marry an Austrian,” she added. “Even a fortune teller told me this. I just did what people expected me to do. So what’s all the fuss about?”

Nancy had a point there. For months, the professional stargazers had been predicting she would soon be the bride of Oscar-winning Maxi Schell.

The Show Biz columnists said it. The movie magazines said it. Nancy’s studio publicists hinted it. Neither she nor Max denied it. And one fan magazine was going to press with a picture of Nancy and Max on the cover when the long-awaited wedding suddenly chimed loud and clear.

Only the Austrian she promised to love, honor and obey wasn’t Vienna-born Max!

The man she married was Innsbruck innkeeper Peter Pock, a surprise entry in the Suzie Wong Sweepstakes.

If she had suddenly eloped with Frank Sinatra, the movie world could hardly have been more stunned. Not only was Pock an “outsider,” completely unknown to Hollywood royalty, he also seemed incredibly young to have walked off with screenland’s hottest piece of property.

He is only 22, a year younger than Nancy.

They met while she was in Austria making “The Main Attraction,” her latest movie. As soon as he gazed at her lotus-petal skin and luscious figure, Peter knew she was the Main Attraction for him.

A few weeks later, Nancy and the movie company moved to London. Peter followed, in pursuit of the Six Happinesses — old Chinese term embracing ali sorts of delights.

She finished work on the film last June 6. The following day, she and Pock appeared at the Paddington registrar’s Office in northwest London, where they were spliced in a 15-minute civil ceremony.

Then the happy couple took off for Austria, so Nancy could meet his family, and Hong Kong, so he could meet hers.

If nothing else, the marriage proved Kipling was wrong when he said “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet.”

It also proved that it’s true what they say about Chinese girls — they’re just as unpredictable as the others.

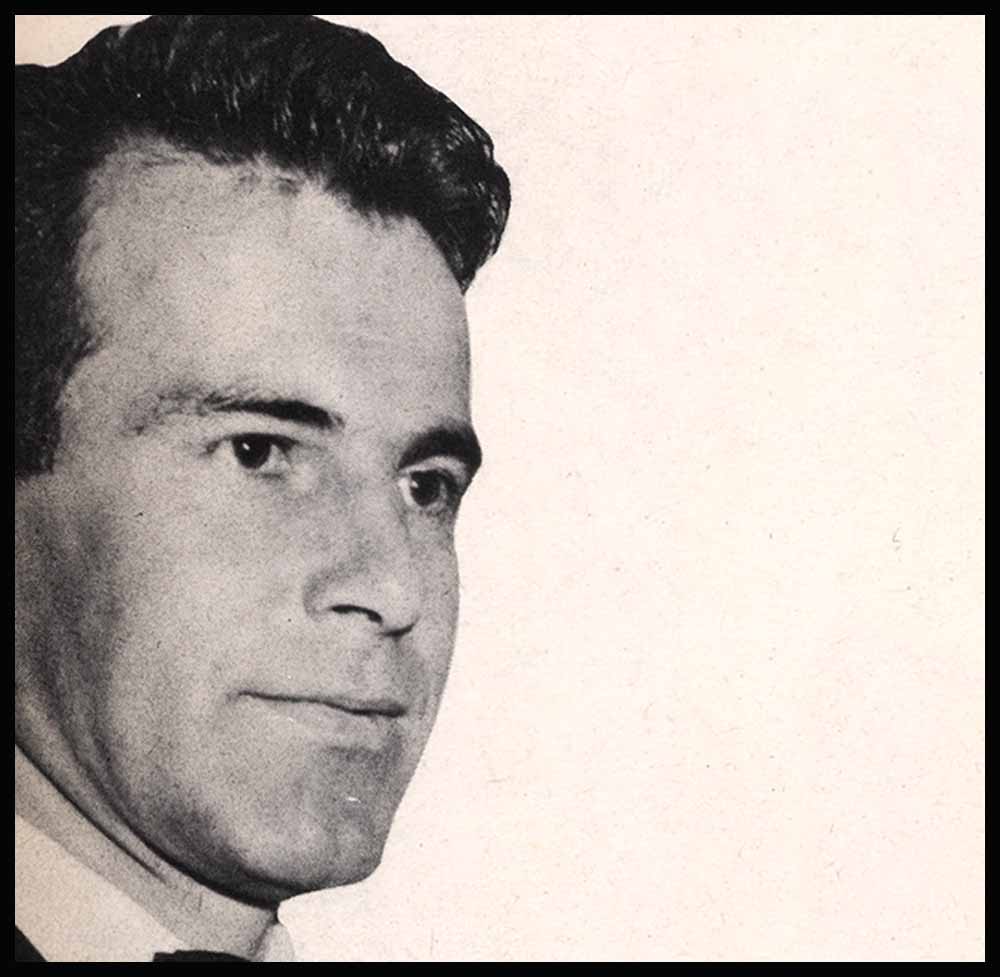

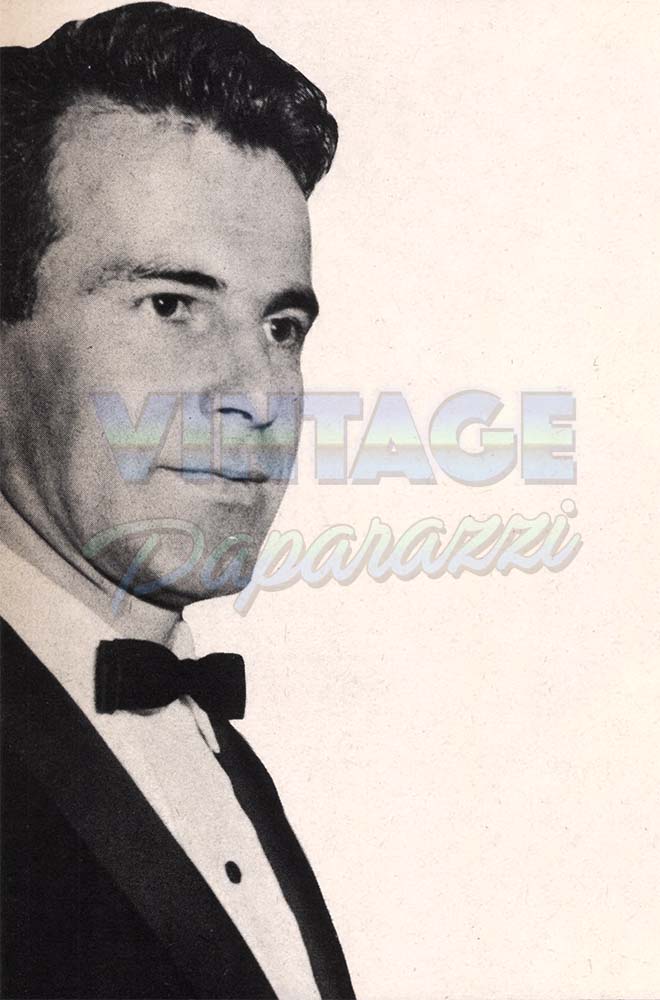

So what happened to Maxi and his much-publicized courtship?

The INSIDE STORY — hot from inside a fortune cookie — is that Schell wasn’t Schnell enough.

When he should have run, he walked; when he should have walked, he sat down. Max had the inside track to Nancy’s heart, but he balked on the home stretch to the altar.

Old Chinese proverb say: You can’t have your fortune cookie and eat it too.

Max thought he could. But a China doll like Nancy can’t be placed on shelf and left there like Schell’s gold-plated Oscar. This real, live doll wanted a real, live husband — not just an admirer.

Until Peter Pock picked his pretty passion poppy, Maxi had Nancy pretty much to himself. For months, they were inseparable. They toured the New-York- Las Vegas-Hollywood circuit together, held hands in romantic bistros, went for moonlight rides in her white Jaguar sports car and moonlight dips in her swimming pool.

But Max didn’t pop the big question. And Nancy couldn’t ask him to marry her. After all, she was brought up in the Orient where females must wait for the menfolk to make up their minds — and then must dutifully obey.

About all she could do was drop discreet hints in the newspaper columns, hoping Maxi would read them.

“In China everybody believes in fortune tellers,” she said on one occasion. “I believe in them. They are usually right. In Hong Kong, a fortune teller told me I would become an actress, would visit London and Hollywood — and would marry when I am 22.”

She was 22 when she made this statement. And Max was her only boy friend at the time. But he was in no hurry to make the fortune teller’s prediction come true.

On another occasion, she said: “If she is mature and very much in love, a girl should get married right then, regardless of age. The trouble is many young Americans marry to get away from home or because they want to make love.

“That is not enough. Marriage should be more than sex. You have to be able to talk to your husband. You can’t just sit around and stare at walls between love-making.”

Nancy and Max did plenty of talking. But he never got around to the topic that was uppermost on her mind.

As if to assure him that he wouldn’t have to worry about which movie star wore the pants, she told an interviewer: “If I marry somebody who is an actor, I stop acting.”

Though these obvious remarks would have hit some lovers with the force of a bazooka shell, they flew right over Maxi’s handsome head.

“Other people keep hearing the music of wedding bells,” one of his pals observed. “But Max is tone deaf.”

He parried all questions about his romance with an enigmatic smile and vague statements of affection for Nancy. Following his lead, Nancy answered the queries with the coy comment: Max? Who’s Max?

“I don’t have to ask how you feel about Max,” a famous columnist told her. “Your face lit up when I mentioned his name . . . and does every time I repeat it.”

Glowing like a Chinese lantern, Nancy replied:

“I hope his face lit up every time you mentioned mine — the dog.”

As the romance dragged on without any new developments, item-hungry scribes thought they might be able to jar a proposal out of Max by beating him over the head. Some of them wrote that he had jilted Nancy.

These items hurt her deeply, but failed to achieve the desired results.

“When it was printed that I ran away from her,” Schell said, “she was like a lily that had its neck bent in a heavy strorm.”

To show Hollywood that the poison-pen artists were wrong, Nancy and Max put on an even more ardent show of togetherness than before. And all the old marriage rumors were dusted off and put back into circulation.

Not even their careers, it seemed, could separate the young lovers for long. On location in Europe, Nancy sneaked off the set frequently to phone Schell in Hollywood. When he went to Germany, she shuttled back and forth between London and Munich to be with him as much as possible. And he flew to London to visit her.

At Shepperton, England, last March while playing a circus bareback rider, Nancy fell off a horse three times in 15 minutes. She suffered body bruises and a sprained ankle.

As soon as Max learned of the accident, he sped to her bedside with candy, flowers and words of good cheer. Nancy was so glad to see him that her large brown eyes filled with tears.

Now, if ever, was the Moment of Decision. And Max again let her down.

“The Chinese do not read Shakespeare, nor do they understand our music and writers,” Schell told an interviewer around this time. “They have their literature, music and customs which we do not understand.

“Her family would be as upset as mine if we rushed into marriage.”

Maybe Nancy doesn’t read Shakespeare, but she reads the gossip columns. And she didn’t need an interpreter to get this roundabout message. Schell clearly had no intention of “rushing” — or even crawling — into an East-West merger.

However, he could not have been more wrong about Nancy not understanding Western ways. The only thing she couldn’t understand was why the man who said he loved her didn’t want to marry her.

Nancy actually knows as much about Western music, literature, art and customs as Schell does. Maybe more. Daughter of a wealthy Chinese architect and a beautiful Scotch-English fashion model, she was educated in a Hong Kong convent, and English boarding school and London’s Royal Ballet School. She danced with the Royal Ballet for two years before returning home to Hong Kong to open her own dance school.

Then the cultured world of Nancy Kwan was suddenly changed by “The World of Suzie Wong.” Touring the Orient for a suitable Suzie to star in the movie version of the Broadway show, producer Ray Stark ran an ad in a Hong Kong paper. Nancy showed up the next day to apply for the part.

Impressed by her fragile Eurasian beauty, stunning shape and the lovliest legs since Marlene Dietrich lifted her skirts for the French Foreign Legion decades ago, Stark signed her to a long-term contract.

But before she got the Suzie role she had to travel around the world and back home to Hong Kong again.

First she went to Hollywood for acting lessons. Then to Ne w York as understudy to France Nuyen in the “Suzie Wong” stage play. Then to Canada with a road company of the same show.

She was in Toronto when Stark phoned her from London and told her to catch the first transatlantic jet. France Nuyen, who had been tapped for the movie Suzie, was having trouble with the part, her weight and her emotions. Heart- broken over a busted romance with Marlon Brando, she was drowning her sorrows in calories.

Brought to London to replace her, Nancy finally hit the jackpot. Two years and more than 25,000 miles after she left Hong Kong, she returned in triumph as Suzie Wong, the soft-hearted YumYum girl.

Asked how she landed the part, she replied:

“The insurance people thinks it’s because I’m the producer’s girl friend. That’s what people always think when an unknown gets the part, isn’t it?

“But the fact is I’m not Ray Stark’s girl friend at all. I was under contract to him long before I was chosen for the picture.”

To Hollywood-trained ears, such candid comments were as remarkable as a snowstorm in the Sahara. Uncertain what she might say next, studio officials put a high-powered publicity crew to work creating the “Nancy Kwan Image.”

The flacks were told to give her the full “star treatment” and mold her into a combination Marilyn Monroe and Anna May Wong. They also had orders to intercept any more pearls of Oriental wisdom that might fail from her lovely lips.

The press agents wrote cute, funny and profund remarks for Nancy to use during interviews, depending on the questions. But Nancy had a mind, and a tongue, of her own.

Whatever she was asked she answered honestly, frankly discussing everything from Honk Kong brothels and American morals to women’s fashions. Asked about her favorite costume, the split-skirt, high-collar Chinese dress called cheong-sam, she said:

“A cheong-sam has slits up the sides because Chinese girls have pretty legs. They like to show their legs. Japanese girls have pretty necks, so they wear a kimino with a collar away from the neck. American girls have big busts so they wear tight sweaters and low-cut gowns.

“The height of the slits in a cheong-sam skirt depends on what type girl you are. Suzie Wong, a Yum-Yum girl or prostitute, would wear skirts slashed to the thigh. My skirt slits are five inches high.”

Of the movie that made her an instant international star, she said: “It’s a small picture, very unimportant but not too bad in general, but I’m lousy in it. Of course I’ve only seen it twice and I think I get better each time I see it.”

And she dismissed Marlon Brando with the scathing comment: “I understand he likes Oriental girls, but I am not impressed. He means nothing to me.”

While her refreshing candor endeared her to interviewers, the studio brass was kept in a constant state of suspense.

“We’ve got a million-dollar investment in this kid,” one movie mogul grumbled. “We can’t let her run around shooting off her mouth anytime she feels like it.”

Her attitude towards her career worried the studio even more than her unrehearsed remarks. Though she was a full-fledged star in her first movie, Nancy was not particularly impressed. Privately, she told friends in Hong Kong and in Hollywood she’d gladly swap stardom for marriage.

Ali she needed was the right man. For a while, she thought she had found him in Maximilian Schell. But he didn’t agree with her old-fashioned Oriental notions on Career versus Marriage.

Finally convinced Max would never marry her, Nancy began dating Peter Pock and married him on the rebound. This sudden move caught the artificial world of Nancy Kwan completely by surprise and sent its tinseled props tumbling.

Studio officials were afraid she would walk out on her contract after the costly buildup. Columnists, press agents and fan magazines were sore because they had no advance warning. No one in her Show Biz world had even heard of Peter Pock, Innsbruck innkeeper.

As for Maxi, who should have realized what would happen, he was the most surprised one of all. But the explanation was simple enough:

Nancy simply got tired of playing the old Schell game.

—By JAMES ROBERTSON

It is a quote. Inside Story MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962