The Girl you Know As Marilyn Monroe . . .

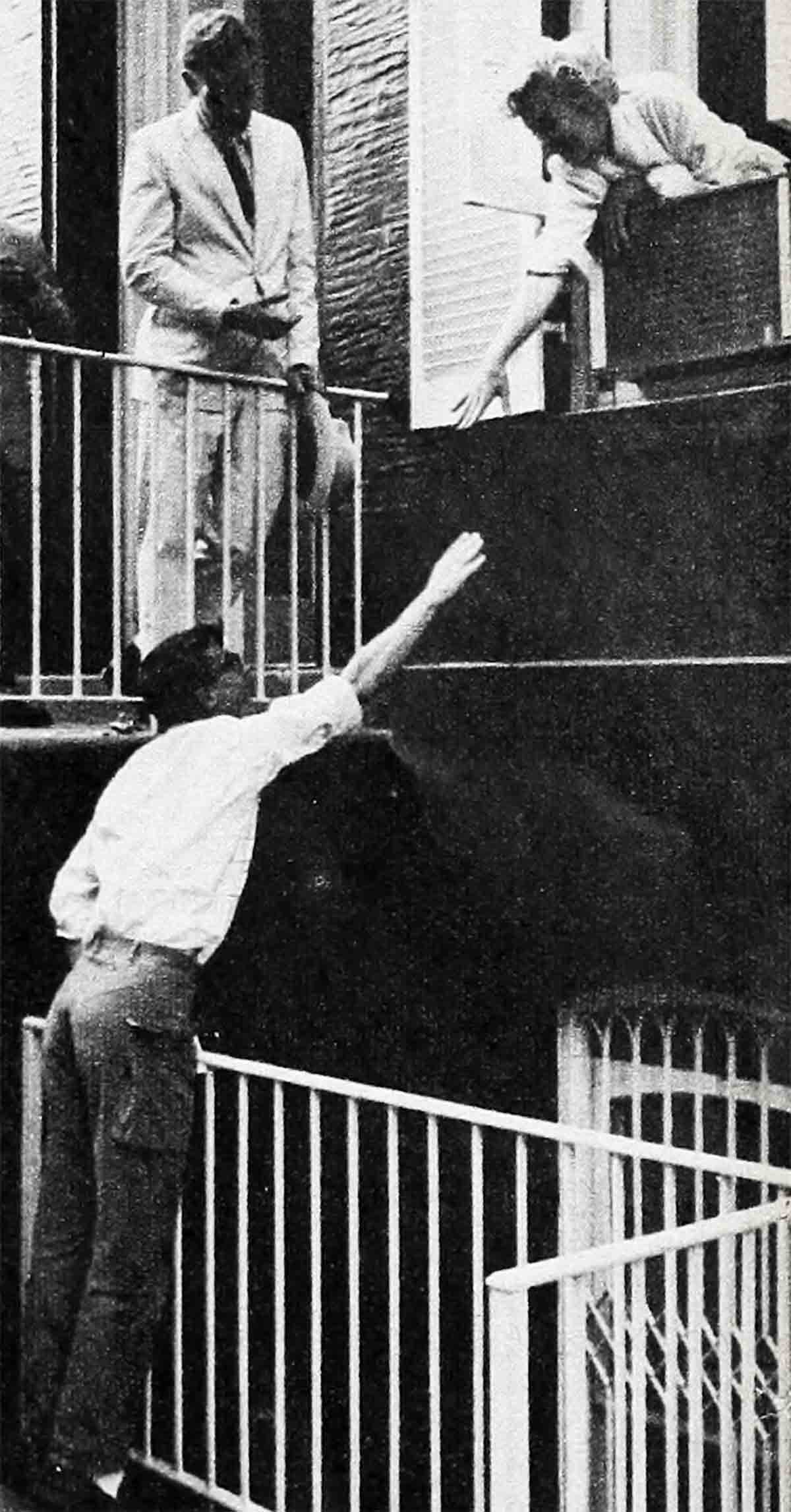

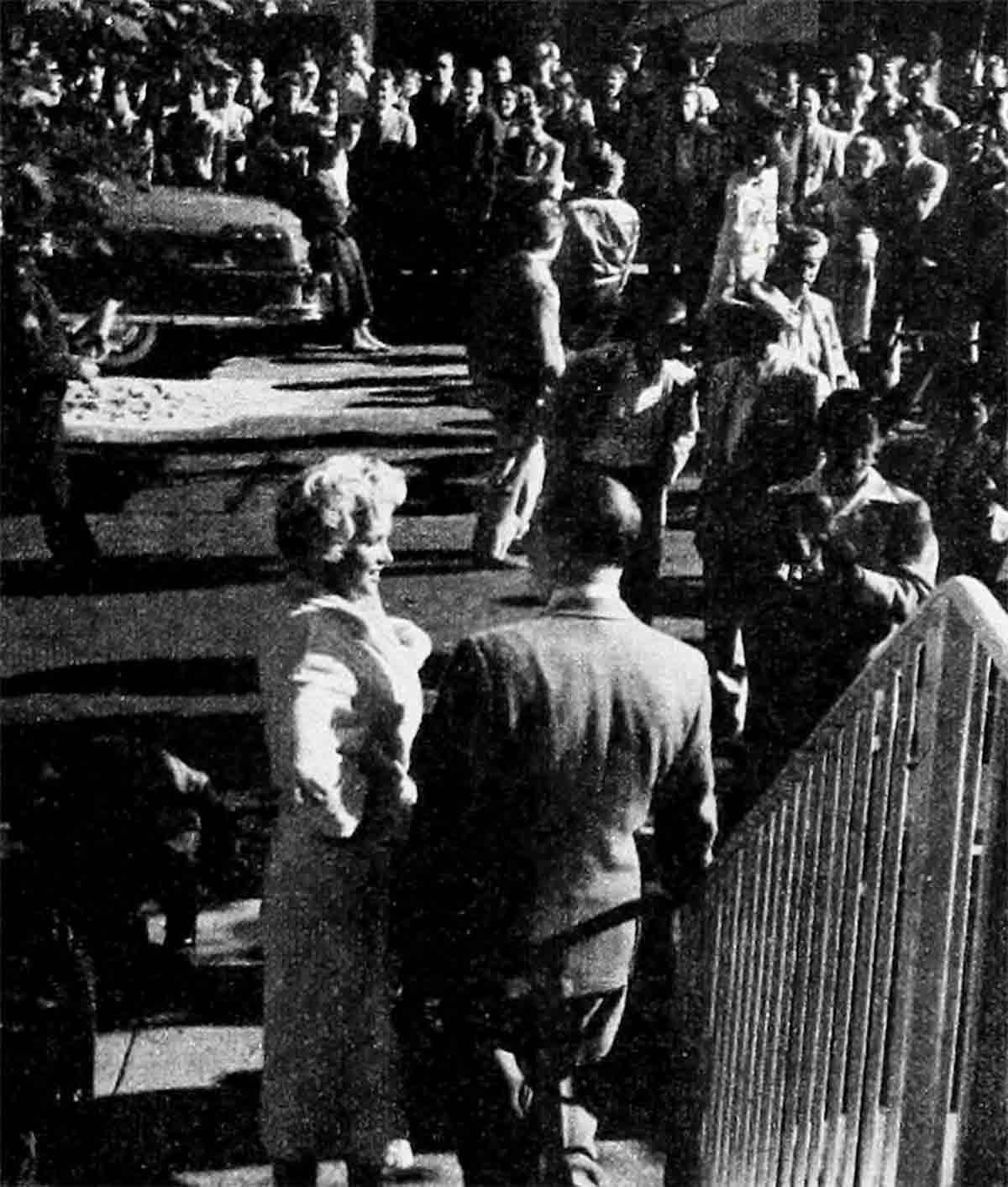

Delighted youths, many of them high-school students, surged against barriers held by hard-shouldered cops and chanted in happy, demanding cadence, “We want Marilyn!”

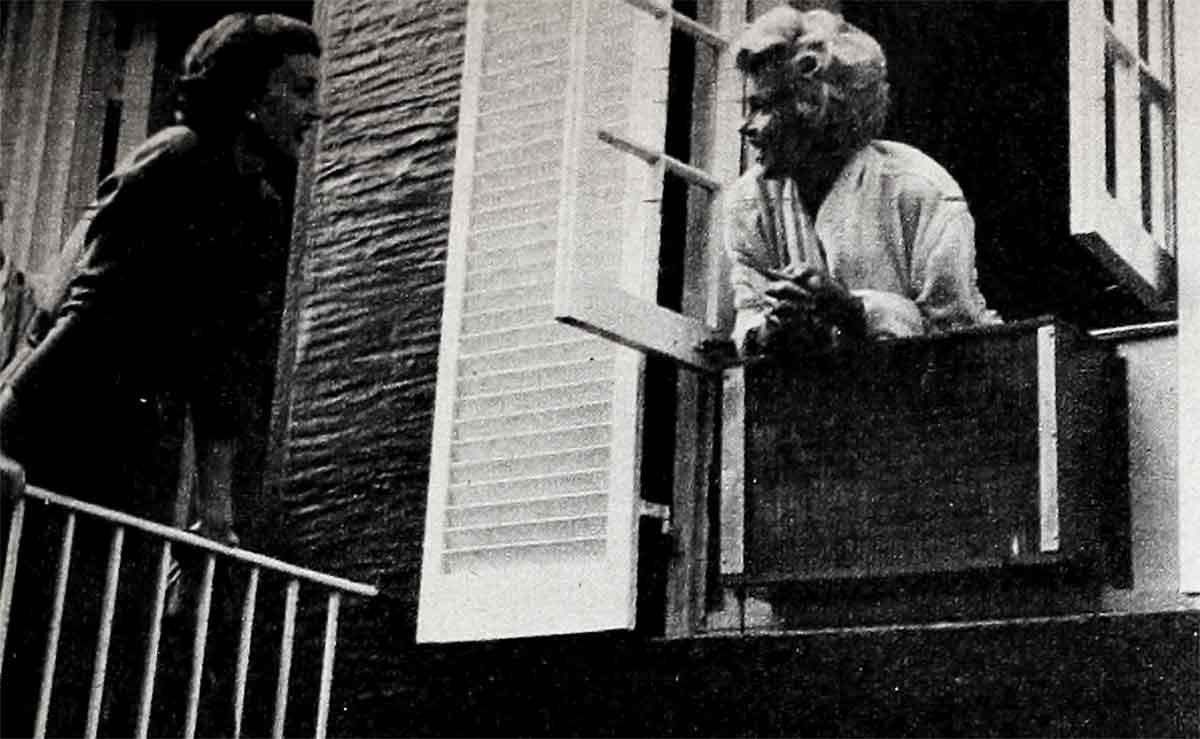

Focus of the commotion was a trim. freshly painted town house on Manhattan’s East 61st Street. Traffic had been blocked off. In theory, the cleared space was reserved for 20th Century-Fox director Billy Wilder’s crew to film a sequence in “The Seven Year Itch.” However, half a hundred news photographers invaded the motion- picture camera area.

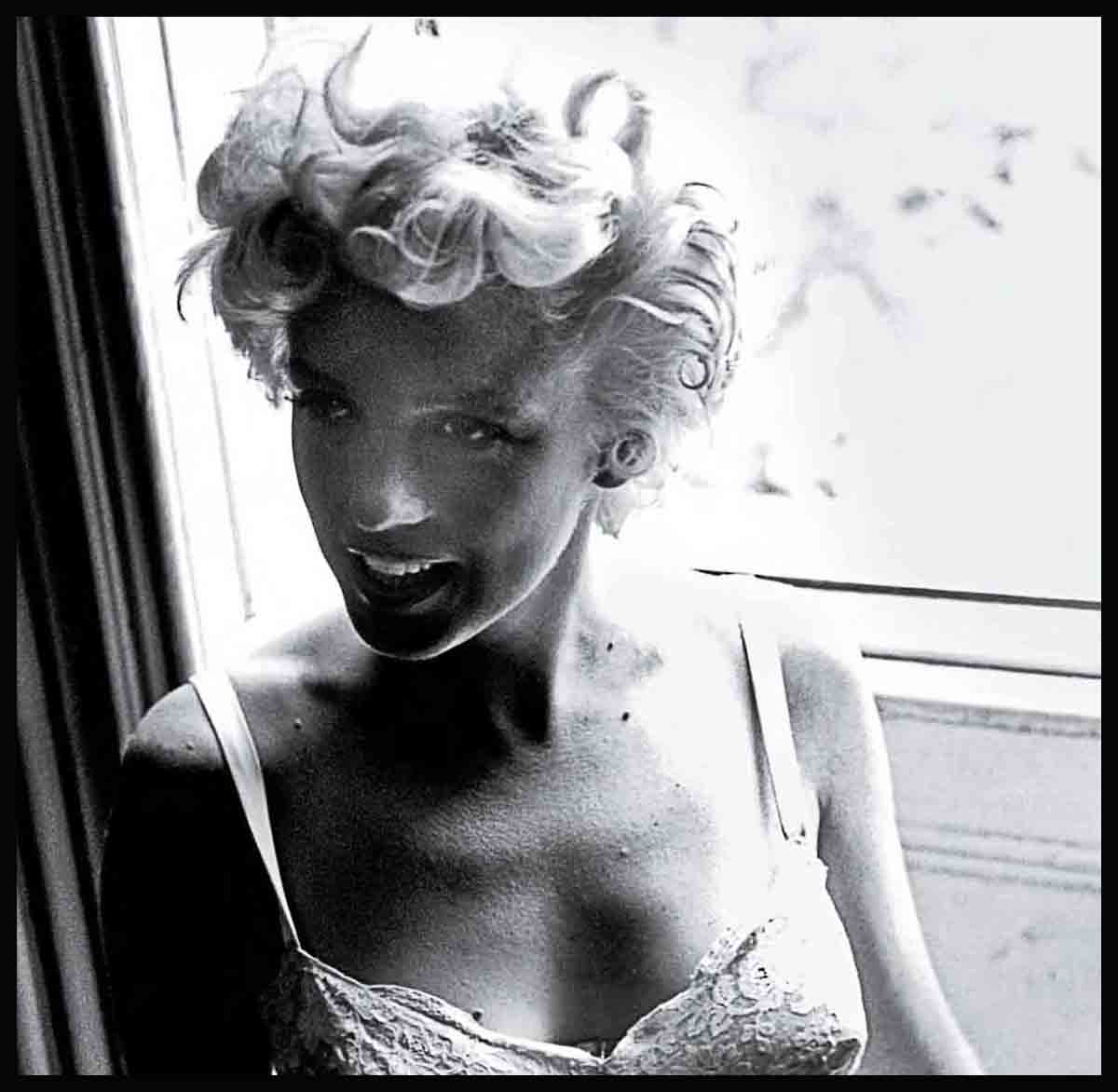

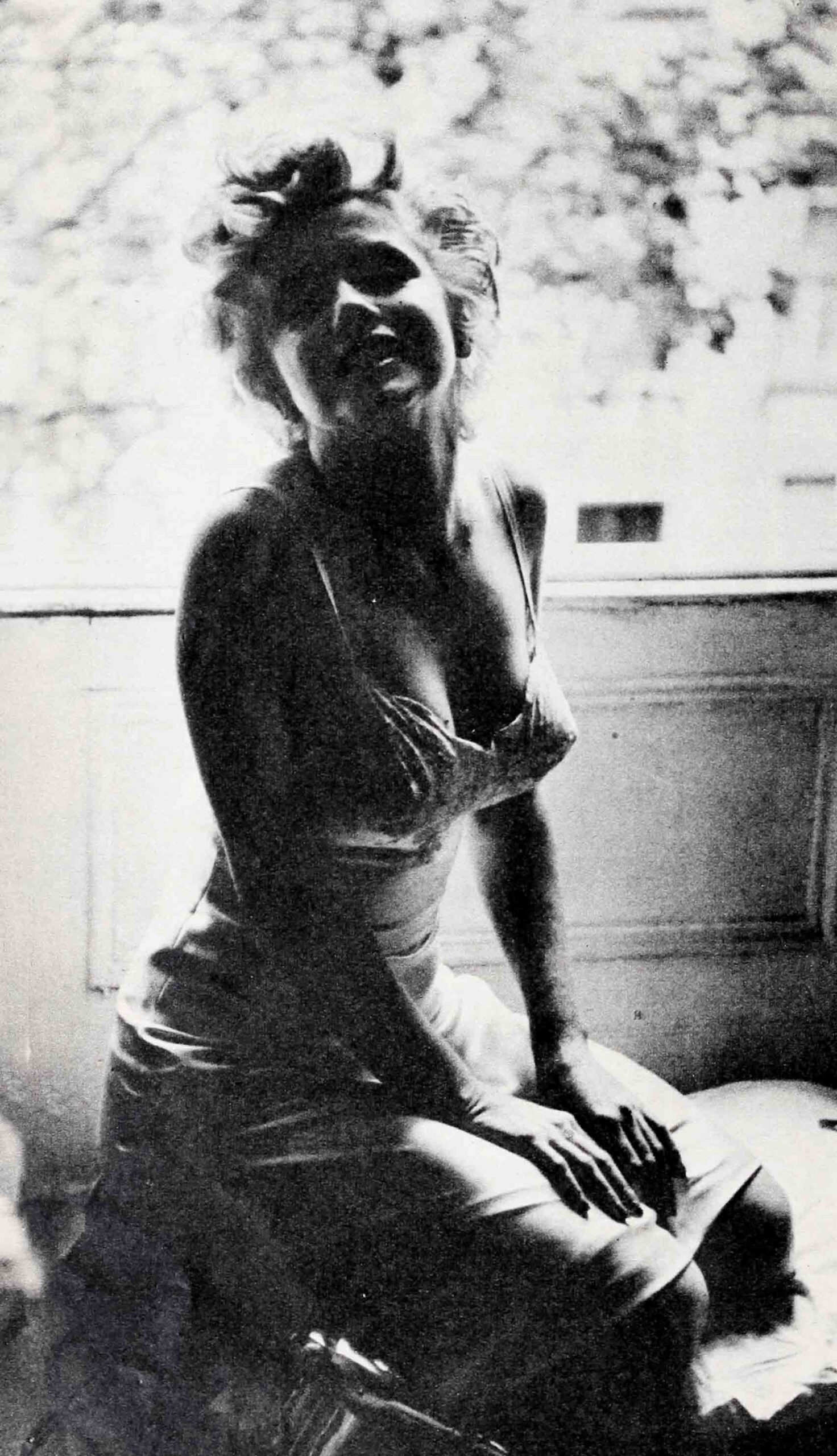

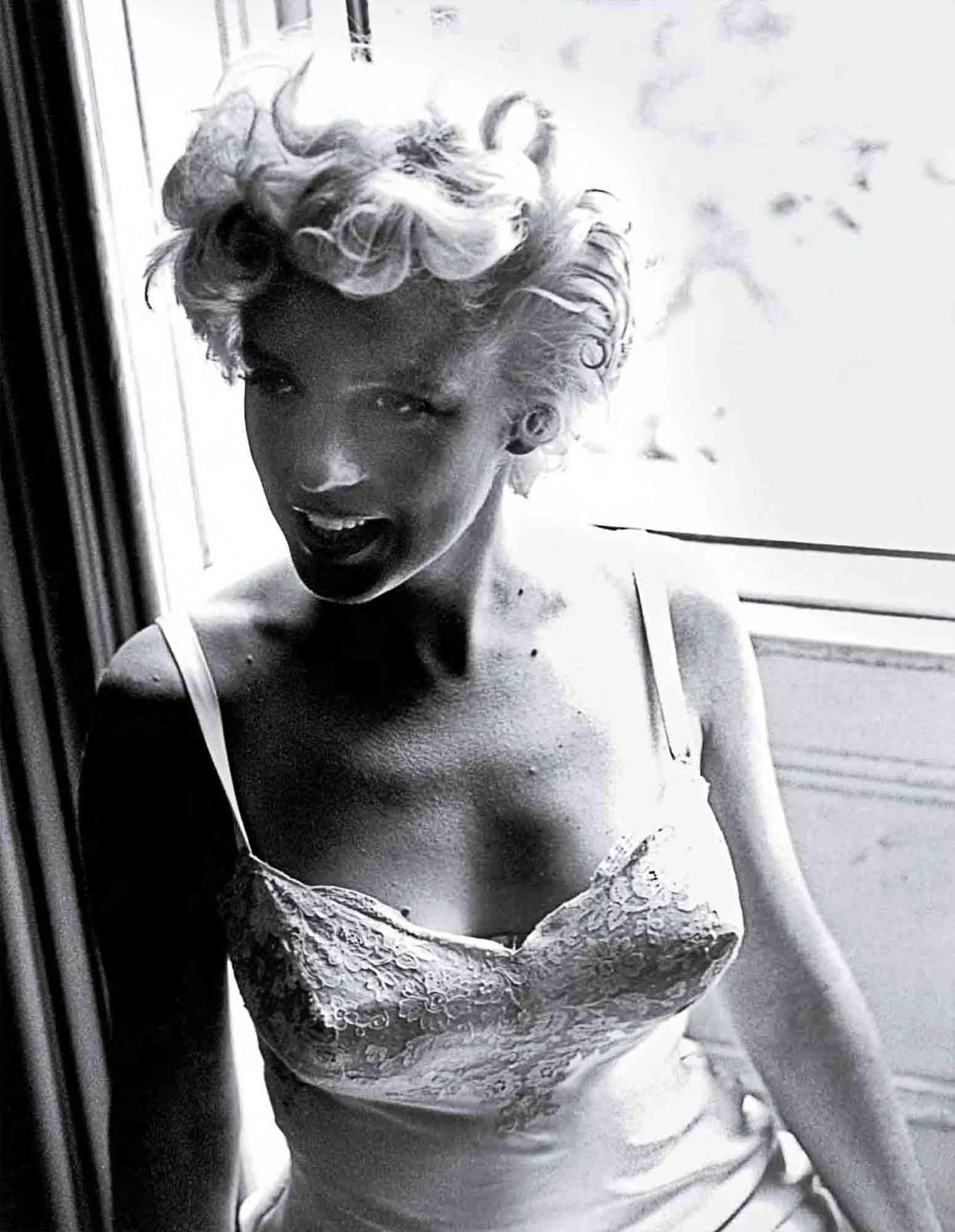

All lenses, as well as the eyes of the crowd, were aimed at a second-floor window where Marilyn Monroe, clad only in a revealing lace-yoked satin slip. fluffed her platinum tresses and called down to her entranced leading man. Tom Ewell, “I just washed my hair.”

Certainly it was far from the year’s most brilliant line of dialogue, but Marilyn held her audience. When the director called for silence the crowd hushed. Then, as Marilyn finished the sentence and vanished from their sight. there was a sigh and the boys again raised their chant, “We want Marilyn!”

Little did. the fans making up that crowd realize that Marilyn was acting out the third act of a drama in which they were unconsciously playing a part. These were the moments that Marilyn had once visualized in a dream—the dream was a reality but the enchantment had somehow escaped. For Marilyn knew that tears would soon replace the impish grin which even then held a trace of tiredness, a trace of strain.

When you look back at Marilyn’s life across the years, a personal drama as well-defined and tense as any master-playwright’s best effort was being played that day.

Act I of that drama was the longest, nearly twenty-years in shaping. In its troubled prologue, Marilyn’s mother and father found themselves unable to cope with the despairs of the depression. In consequence—and in a manner reminiscent of classic fairy tales—their tiny daughter, the future golden princess was reared by strangers.

No shining knight came to her rescue. Instead, with a determined vision of the future, she worked to earn her own kingdom. Her ambition put her first on magazine covers and calendars, then into movies. There were many discouragements. Two studios signed her, then dropped her, and the experiences hurt.

But through it all she had faith in her own destiny, and the camera lens was always her ally. The first goal was won when it brought her photos to those who were even lonelier than she—the GI’s drawn into service by the Korean war. As a curvaceous blonde starlet in a bathing suit, she brightened barracks walls in Seoul, Istanbul and Berlin.

Thus the emerging star acquired that first asset of a reigning queen—a host of loyal men-at-arms. Again the motion-picture cameras took notice of her.

Act II brought fame, love and a second curtain crisis better cast and more dramatic than that of a stage play.

It opened with Marilyn Monroe strolling through brief bits to decorate the dreary scenes of a succession of even drearier memati One of them served her well, for because of it she got her first glimpse of the wondrous towers of Manhattan. Brought into New York at the rate of a hundred dollars a week to exploit a picture called “Love Happy,” she was, for an afternoon while she met exhibitors, installed in a magnificent hotel suite. But in the evening, after they had departed, she was moved to a tiny room. She made up for it by ordering caviar for breakfast and charging it to the film company.

The still photographers—the men back of the Speed Graphics and the Rollies—gave her more consistent billing, for she had both the mien and manner to delight them. One veteran photographer remarked, “Marilyn opens her eyes a second before you snap, then blossoms like a rose.” Photo editors, too, became her fans. A national picture magazine termed her “a serious blonde who can act . . . the effortless mistress of the slow, calculated walk . . . the brightest star since Lana Turner.”

Then Marilyn was accused of appearing coyly in the altogether on a highly popular calendar. Marilyn proved she could pitch a curve as well as pose in one. Freely she admitted she was It. She also admitted another thing considered by some to be very bad etiquette—that she had posed because she was broke and needed the money. Asked what she had on during the shooting, she replied, “The radio—but it was all right. e photographer’s wife stayed in the room.

It won her newspaper space but not the approval of her feminine colleagues.

Asked why she hadn’t skinned alive a certain female columnist, she answered, “Because it was more cruel to leave her skin as it was.” Rubbing salt in the wound, she candidly stated she preferred men to women interviewers. “Men and I have a mutual appreciation of being male and female.” She remarked, too, “I don’t mind being in a man’s world so long as I’m a woman in it.”

In like mood was her condemnation of too much sun tanning, the famous, “I like to feel blonde all over.”

At the same time she was kidding her critics, Marilyn Monroe was earnestly pursuing a sounder campaign for answering them. To broaden her knowledge and to equip herself for the stardom she was determined to achieve, she enrolled in university classes to study philosophy and literature (“I want to know not only what people write but what makes them write it”). She also studied drama and eventually found a coach who suited her, Natasha Lytess.

When she was ready to call attention to this phase of her interest, she did so with a characteristic Monroe gesture. The collection of playscripts in which hand-written notes had been inscribed by the famed director, Max Reinhart, was to be offered at auction. Expecting no competition, representatives of two universities conferred, it is said, and quietly decided what each would bid on and at what price. They reckoned without Miss Monroe. She went into the auction and bought up the entire collection. Later, when much turmoil arose because they had fallen into the hands of a private individual, she permitted Reinhart’s son, Gottfried, to buy them back.

As the dust settled after that incident, certain writers, still refusing to believe that the sexy beauty could have a serious desire to own or study the playscripts, redited the idea to Marilyn’s drama coach Miss Lytess and called her a “Svengali.”

Whatever her role in the matter, Miss Lytess aided Marilyn. Marilyn found in her coach not only a teacher but also a woman friend who believed she was more than a pinup girl and said so. Later, as Marilyn’s growing skill in handling roles drew surprised praise, Miss Lytess disclaimed credit, saying, “All I taught her was to open up and let go of her voice and body and not telegraph her emotions ahead of time.”

One emotion which Marilyn never ceased telegraphing was her driving desire for good parts. Learning, in 1951, that “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” was to be made into a picture, she set her heart on the lead and gambled more than she could afford to go to New York to study the stage play.

The trip was far from a red-carpet tour. Although she had already appeared in a string of pictures as long as your arm, she passed unnoticed on the streets. No one asked for her autograph, she ate in a cafeteria and, as she recently confessed, she was a long time paying her hotel bill.

Worrisome though the trip was, it proved to be—in both her professional and private life—a turning point. She got the role. When “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” was released by 20th Century-Fox, it grossed $5,100,000. Her performance, together with her role in “How to Marry a Millionaire,” put her at the end of 1953 on a new kind of pinup list—sixth best boxoffice draw.

The private life importance of that New York trip before she was cast in “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” centered around Joe DiMaggio. Marilyn had met the Yankee Clipper in Hollywood and, since business had taken him to Manhattan, they met again and Marilyn went home feeling sure he was the most fascinating man she had ever known.

Her feeling about Joe, however, was an emotion she well knew how to keep to herself. After two years, Marilyn, again in a surprise dramatic move, married Joe. And with a winning gesture, chose, on her honeymoon tour, to visit her first staunch admirers—those devoted men-at-arms still stationed in Korea.

Act III finds Marilyn still on stage—but this time it is as a bewildered, hurt young woman. Her smile flashed in answer to the admiration of the fans in Manhattan but that smile masked an inner uncertainty about herself as a wife. Against elegant backdrops of El Morocco and the Stork Club, Marilyn appeared with Joe. Marilyn admitted freely she’d never realized how popular Joe was until the day when she opened the trunks holding his vast collection of loving cups, medals, rings and cuff links, all prizes which had been awarded him. Marilyn had a chance to show off her mink coat, the first she ever owned. When someone protested that it was too warm for her to wear it she replied, “Joe gave it to me. You can just tell people I don’t know any better.”

Marilyn was every inch the movie star on this visit to New York, and unfortunately, that every inch held heartbreak which was to blaze forth the minute she returned to Hollywood. She played the final dramatic scene in her marriage, not before her fans, but before some five-hundred newspaper photographers and reporters, on the front lawn of the house where she and Joe had been able, always before, to shut out the world of Hollywood, baseball and the fans that idolized them both. Now, the world knows the sorrow that this house contained. A house in which the girl you know as Marilyn awaits whatever action is handed her in the script of life which she is yet to see.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955