We Could Write A Book—Esther Williams & Ben Gage

“Go see what’s new with Esther.” The last time MODERN SCREEN gave me this ultimatum I wound up at 180th Street and Vermont Avenue, which as anybody in Los Angeles knows (unless he lives at 179th and Vermont), means a safari. This was because Esther was visiting her high school.

This time there was something new with Esther. She and Ben had just returned from a seven-week tour of the country with a show of their own that included singers, dancers, a trampoline act and one elephant, as well as thirty-five minutes of Esther, both wet and dry. I held a hope that the tour might be worth a story, a hope that was rather dim because jaunts of this type usually sound like the itinerary of a Pullman porter and come out as interesting as a cigarette butt.

I met Esther in the early hours of darkness, at a Beverly Hills restaurant famed for its quiet corners. She collapsed into the seat beside me, admitted she could be done in with a hatpin, having spent the last few hours in an exhausting business meeting, and asked with characteristic directness what I wanted to write about this time.

“The tour,” I said, “except that it’s probably pretty dull when summed up.”

“Ha,” said Miss Williams. “Dull! Ben figures he’ll write a book about it.”

At that moment Mr. Gage approached and landed in the opposite seat. Ben is as loquacious as Esther, and together they make copy fly like popcorn.

“Our itinerary is requested,” Esther in formed him.

“No soap,” said Mr. Gage. “I intend to write it myself. Should make a very funny best-seller.”

“Oh, relax,” said Esther. “You know you’ll never get around to writing it.”

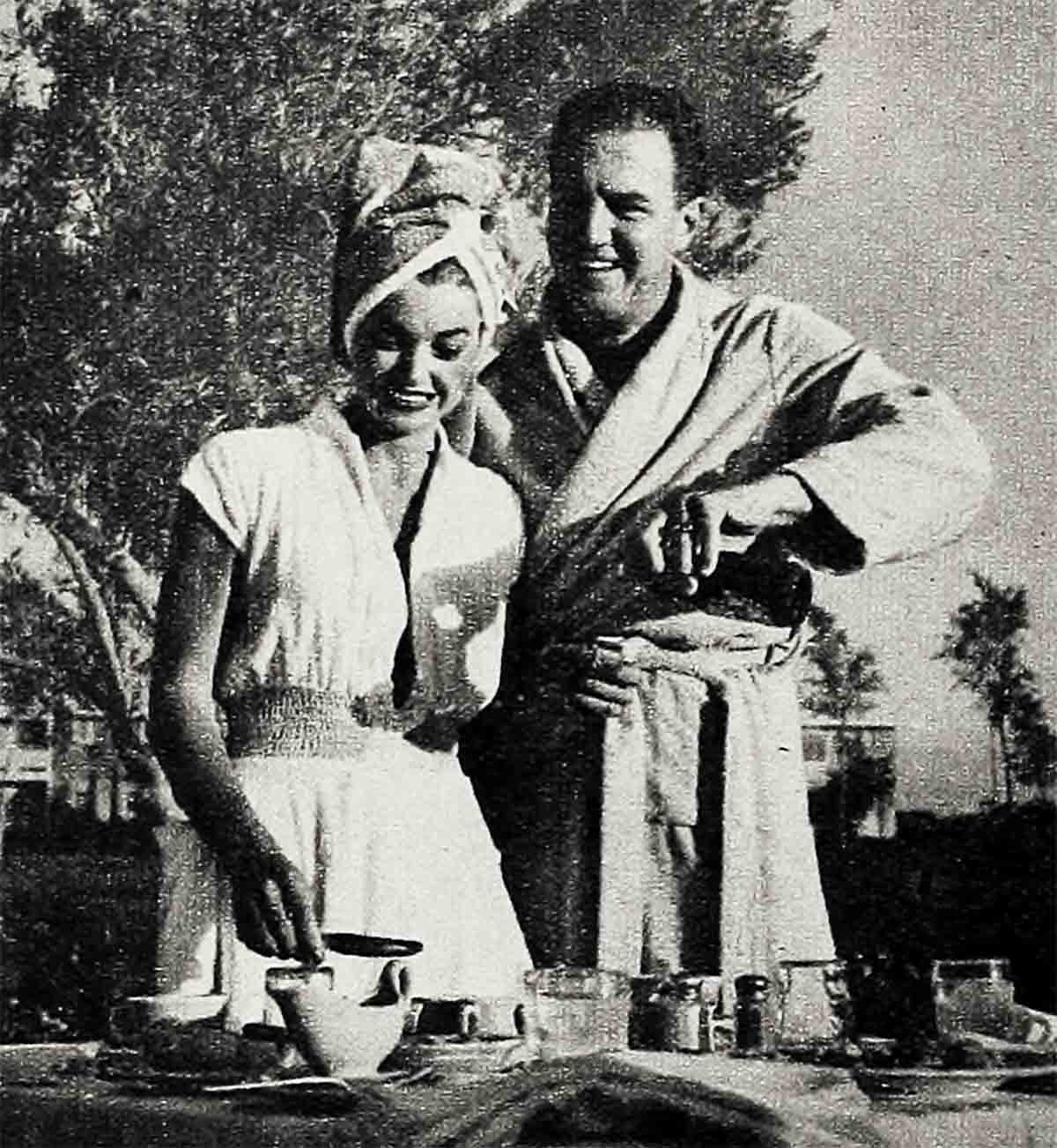

And with that they began to spew anecdotes so fast that the studio press agent at my left had to spoon my dinner into me so that my hands were free for taking notes. The show was a “break-in” for the future, they said, because they plan, beginning in the spring of 1956, to devote half their time each year to a traveling aquacade. Esther had been lukewarm about the whole idea, principally because it would mean leaving the children behind.

“Look,” said Ben. “The road is exciting. It’s an adventure. It’s fun. And it’ll only be a few weeks.”

The tour was booked to open in Albany on September 5. Jupiter’s Darling, Esther’s picture, wound up tardily in mid-August, which gave them just two weeks to get their own show together. Miraculously, they opened on schedule, and naturally, Albany was a hodepodge of rewriting, trimming and adding to the show.

The opening over, they took off for Hartford, following on the heels of hurricane The city was a shambles, trees uprooted, the streets littered, the citizens dazed. And no sooner had the troupe settled itself in the hotel than the radios began blasting warnings about a new hurricane. Edna was on her way, they said, and if people wanted to live through it, they’d better batten their hatches, fill their bathtubs with water, stay inside their homes and nail their children to the walls.

“What a jolly day for an opening,” said Esther.

“Dandy,” groaned Ben.

The others weren’t so flip. Coming from California, they were conditioned to earthquakes, but not to hurricanes. With pea-green faces they shuffled through the hotel, studying its structure and calculating their chances. The morning brought rain and high winds and the news that Edna would hit with full force about noon.

“You might as well give a show in the middle of the Mojave Desert,” said Esther. “There’s no sense to this. I’m going home, that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going home.”

But noon passed, and so did one o’clock, and Edna took her eye elsewhere. Ben and Esther, devouring details from the radio, breathed a sigh of relief, and bolted for the phone. “This is Ben Gage and we’ve got a show going on at three this afternoon. I understand there’s no longer any danger, that the winds have gone and the weather’s mild. Would you broadcast the news that our show will go on today as planned?”

“Be happy to, Mr. Gage, but the wind just blew down our transmitter.”

The first show went on as scheduled, and the theatre built for 3000 people contained 500 brave souls. Ben opened with some ad lib announcements. “The Pratt & Whitney night shift,” reported the man whose ear had been glued to the radio all morning, “does not have to report for work. The golf tournament has been canceled, and the Annual Fly-In of Light Planes to Nantucket Point is not to fly in. Keep your Piper Cubs on the ground.” He gave them an added word of encouragement. “With all the insurance companies here in Hartford, Edna wouldn’t dare!”

Atlantic City was next, and while they packed, the radio volunteered some interesting information. Atlantic City, it seemed, had just suffered the worst Miss America contest in its history. Nobody was in town. The news of the hurricane had sent the tourists scurrying for home, and the highways between the shore resort and Philadelphia were jammed with people fleeing the coast.

“I’m going home,” wailed Esther, and the rest of the troupe eyed each other nervously.

A booker, up from Atlantic City to catch the show, waved cheerily as he left them. “Well, see you on the Steel Pier in Atlantic City,” he said.

“Have you checked lately?” said Ben. “The Pier is probably in Camden by now.”

“You can’t give a show without an audience,” said Esther. “I’m going home.”

“Now, now, dear,” said Ben, and began arranging transportation. Whereupon he learned the interesting fact that you cannot go directly from Hartford to Atlantic City on either plane, train or bus. Transfer is necessary, and with an elephant, twenty-two people, a water fountain and seventy-five pieces of luggage, it is not advisable to attempt transfer, particularly in the middle of the night. The elephant, fountain, wardrobe trunk and Ben’s golf clubs were loaded on a truck for the trek, and the rest of the group, with accoutrements, piled into a rented bus for the ten-hour trip. It was Sunday night, and the show was due to open on Steel Pier at one o’clock the next day. They were tired and hungry, but the restaurants they passed were closed, due to the combination of the Sabbath, the hour and Edna. They finally convinced a policeman that they would either eat something somewhere or turn into a busload of cadavers, and that gentleman obliged by persuading the owner of a restaurant to open his door at one A.M. The troupe sated itself with the proprietor’s highly-touted onions and cheese and climbed back into the bus, which then took on the aroma of very old lasagna.

Esther went to bed, a process involving the placement of her derriére on a bus seat, her feet in the aisle, and her head pillowed on a bass drum. Ben covered her with a mink coat and whispered a soft goodnight which was lost in the sound of the rap-rap-rap of the bus exhaust. Esther looked up at him blearily. “Is this the fun you were telling me about?”

At eight a.m. they arrived in Atlantic City, quite gamey, and spilled out of the bus into the fresh air. A swim in the Atlantic (Esther’s first) took away the onions and cheese and restored spirits, and shortly before nine Esther hopped into bed in the hotel. “I’ve got to sleep fast,” she said. And while she slept the rest of the troupe went to Steel Pier on a scouting party, cased the dressingrooms, placed the water fountain, hung draperies, and in general got the place ready for the show. When they returned to the hotel, Esther was awake and bright-eyed.

“Well!” she chirped. “Let’s take Atlantic City by storm!”

“I’m glad you feel fine,” said Ben. We’re pooped.”

“Ah, the sea, the sea,” said Esther, not to be undone. “Listen to it pound. I feel great! Let’s go on our big adventure!”

Virginia Darncy, hairdresser, tried to warn her. “The dressingrooms, Esther, you’re not going to like—” Seven hands clapped over Virginia’s mouth.

Esther opened the window and took a deep breath. “This is wonderful,” she said. “Wonderful!” Then she looked at Virginia. “What am I not going to like?”

“Come on, dear,” coaxed Ben. “Hal got us a nice limousine, and we can drive over to the pier.”

“What am I not going to like?” demanded Esther. “What about the dressingrooms?”

But they herded her into the car, along with Virginia, who continued to have her mouth covered whenever she opened it. They drove through streets and over the boardwalk and through a tunnel and stopped before the stage door.

“It looks like a mine entrance,” shuddered Esther.

“What matters is where you work,” offered Ben.

When she saw where she was to work, Esther wasn’t much happier. The floorboards backstage seeped with water, the walls were mildewed, and every time a breaker hit the pilings supporting the pier, the whole structure moved slightly. Esther grew ominously quiet.

“At least you can swim,” said Virginia comfortingly.

“One week here,” mumbled Esther. “Let me see my dressingroom.”

The rest of them had seen her dressingroom, a cubicle so small that Esther’s hoop-skirted ball gowns couldn’t be squeezed into the space, let alone Esther. They looked at her as though she had a short fuse. And Esther looked at the dressingroom. “My laundryroom at home is a glamorous establishment by comparison.”

“I tried to tell you,” said Virginia.

Esther’s high spirits, her joy at being once again near an ocean, had withered and the first show didn’t help matters. To begin with, Steel Pier’s theatre is shaped somewhat like Fifth Avenue. “So long and so thin,” said Esther, “that looking out at the audience it seemed as though all 2900 of them were sitting in one long line. I was sure that the 2870 sitting back of the thirtieth row couldn’t even see the stage, let alone me. And that long white light that came at me—it was like being impaled!”

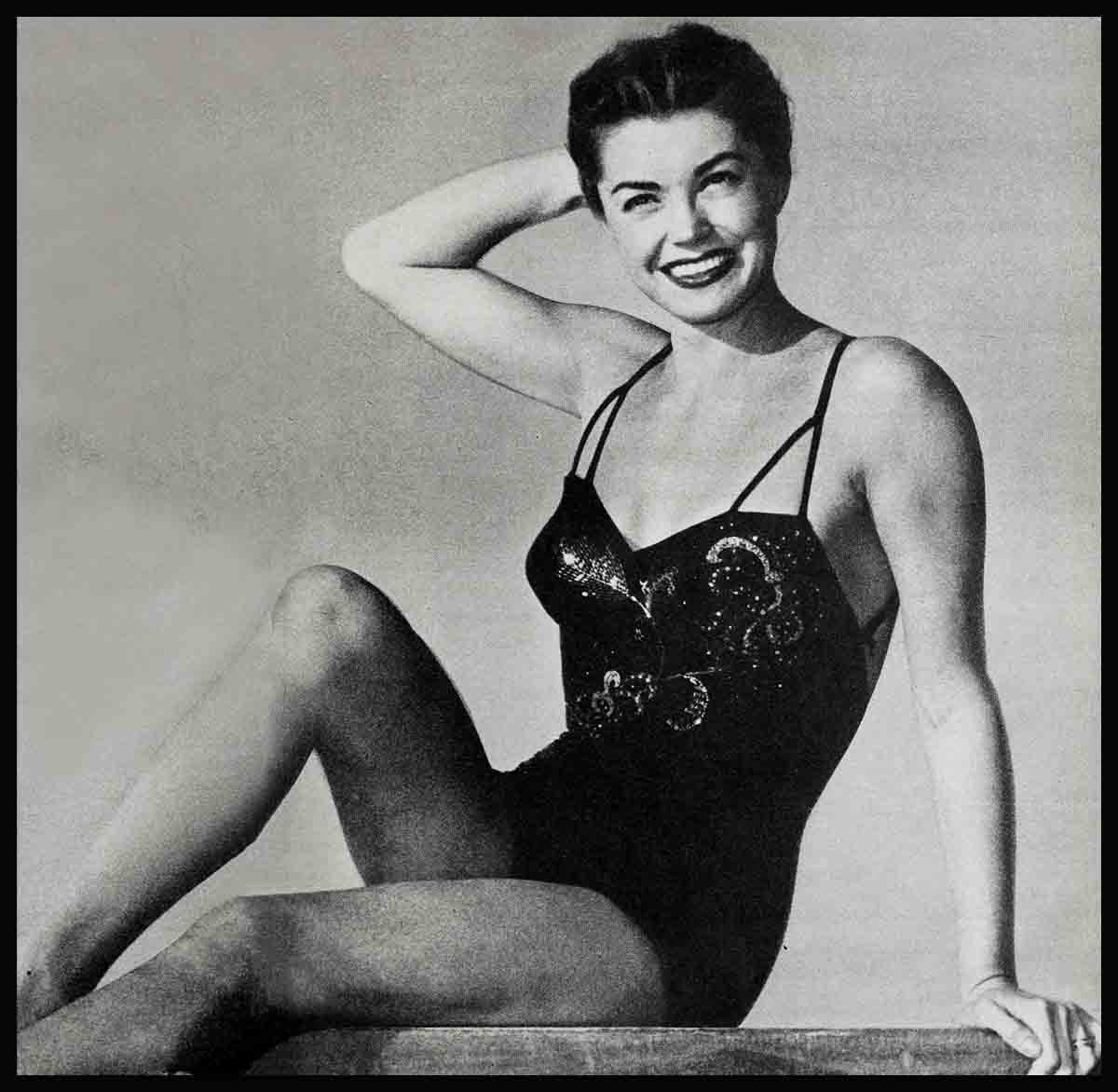

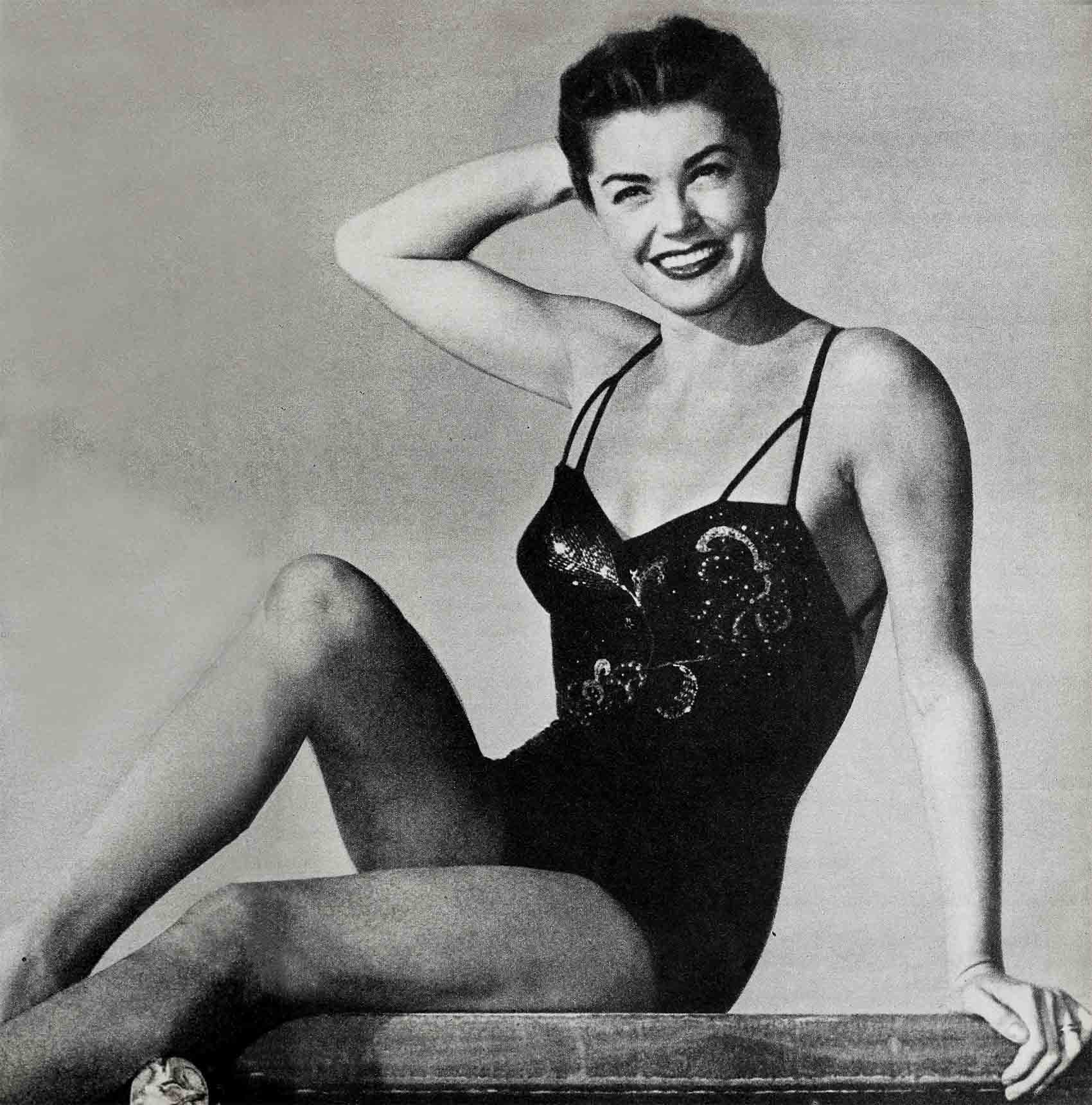

The situation grew thinner when Esther, draped in her sequinned bathing suit, stepped into the water fountain and waited expectantly for the water to begin fountaining. It never did. “You’ve no idea how dry your skin can feel when you know you’re supposed to be wet,” reported Esther. “It began to curl, all over me. I felt like a Frito.”

It was one of those moments that requires savoir faire, and Esther rose to it. “Ladies and gentlemen, this water fountain was invented by my husband, to whom I shall speak very shortly. Will you please come back some other time? I’m sure that with all this ocean around us and under us, we’ll manage to have water come out of the fountain in the future.”

Bowing off, she was caught by members of the troupe to prevent her from hurtling into the rotted wood of the stage walls.

“Well!” she fumed. “Well! I’m going home! Straight home!”

At this inopportune moment, Mr. George Hammid, manager of Steel Pier, chose to make his entrance. He approached with extended hand. “May I introduce myself?” he said politely, and was stopped short in his tracks by the pointed finger of an irate Miss Williams.

“You! You, for one! Take those flowers you sent me and put them in the dressingroom I can’t get into!”

“See you later,” Ben said to the astonished Mr. Hammid, and whisked Esther to the stage entrance. “We’ve got to get her into the car,” he said, “or she’ll go back to California in her bathing suit.”

Back at the hotel, Esther sat and steamed while Ben tried to settle her down. Other members of the show huddled in the next room, their ears flattened to the wall. They decided never to unpack, since they might return to California momentarily.

“I’m not going back there,” announced Esther. “I refuse to do another show.”

“The water will work next time. I promise.”

“Hmphh,” said Mrs. Gage.

“Look, honey, think of the experience you’re getting. This is the groundwork for the aquacade. You can’t quit now.”

“Yes I can,” said Esther.

“Think of the rest of the crew. Think of them!”

Esther shook her head. “I can’t help it. I’m through. I’m going home.”

Ben disappeared, for twenty minutes, during which time Esther called her home, her agent and her studio, using the telephone for a wailing wall. When Ben returned, he dumped piles and piles of money into her lap.

“There now,” he said soothingly, “Look at that! And it wasn’t easy getting it—the box office wanted to count it first. See—that much is theirs, and all this is ours. Think what it will do for our children’s future. Think of the kids.”

“I am thinking of them,” Esther wept.

The thing about Esther is that you can’t keep her down for long, and once she followed with a successful show (during which the waterworks worked), her spirits began to soar. She and Ben grew to know George Hammid well enough for Esther to sound off in her inimitable fashion.

“How long has it been since you’ve seen the dressingrooms?” she demanded.

“A long time, I guess.” Hammid shrugged. “We’ve had lots of stars here and they’ve never complained.”

“That’s because they’re more patient than I am,” said Esther. “You come back there with me and look. George, you ought to be ashamed of yourself!”

Evidently Mr. Hammid was, for he took Esther’s ribbing and by the time they left, new dressingrooms were being built.

By the time they took Columbus and opened in Detroit, the show was going on all cylinders. But Esther was drooping again. Susie’s first birthday would fall on October 1, and over and over again she tried to think of some wonderful gift that would make up for their absence.

“Send her a wire,” flipped Ben.

“You’re a big help, you and your humor,” said Esther.

She began to notice the knot in her stomach that day by day seemed to grow tighter and tighter. And when Ben came back to the hotel late one morning after his first golf game since leaving home, she looked at him with a martyred expression. “I hope you’re real happy. I’m glad somebody can get away from all this pressure!”

That night at dinner, the eve of Susie’s birthday, a worried Ben asked what in the whole world could cheer up Esther.

“That’s easy,” she said dreamily. “If I could just walk into the nursery with Benjy and Kim and Susie and a big paint book, life would be beautiful.”

“And so,” Ben says now, “I knew I had to get those cats to Detroit somehow. I called Jane Boyd, our nurse. It was then six-thirty in Los Angeles and the kids were having their dinner. I told Jane to get the kids on a plane to be in Detroit by ten-thirty the next morning. She said it was impossible but I said it had to be done and hung up. And that did it.”

The next morning he rose early, allowing two hours for the drive to Willow Run airport. As he dressed, Esther opened one eye and looked at him supiciously.

“Where are you going?”

“Play golf,” lied Ben briefly, pulling a sweater over his head. He was already in the doghouse from the game yesterday, but golf was the only excuse he could think of to get away to meet the plane.

“On Susie’s birthday?” wailed Esther. “You couldn’t!”

“Didn’t you send her the wire?” he said.

“One of these days—Pow!” said Esther. “Besides, we have a radio interview before the show.”

“I’ll be back in time. I promise. I’ll only play thirteen holes or something, but I‘ve just got to get out on the course. I feel awful.”

“You and your grass and trees,” muttered Esther. “I don’t know why the elephant didn’t step on your golf clubs instead of planting her big fat foot on my hat.” As Ben went out, Esther threw a shoe at his departing back. “Enjoy yourself, dear,” she said through gritting teeth.

While Ben weaved his way through Detroit traffic, Esther was calling home. The phone was answered by Dr. Raymond LaScola, the Gages’ pediatrician who had been staying in their guest house since his own home burned. The doctor, of course, had been up half the night helping poor Jane get the youngsters ready for the trip. And now, hearing Esther’s voice, he was on uncertain ground.

“Where are the kids?” Esther said.

The doctor coughed. “Hmm? Has anything happened yet?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Esther. “I just want to talk to my kids. Put Susie on. If it takes her twenty-five minutes to even hiccup, I’ll hang on. just so I can hear her.”

“Susie’s asleep,” said the doctor.

“Oh. Well, let me speak to Benjy.”

“He—uh—he’s doing a show.”

“At eight-thirty in the morning?” howled Esther.

“Well, you know how nursery schools are. They don’t know how to live.”

“How about Kim?”

“Where Benjy goes, Kim goes. know that.”

“What’s Benjy doing in the play?”

“I believe he’s a cocker spaniel this time,” said Dr. LaScola.

Esther giggled. “He’s not the type. Ray, what are you going to do about your breakfast?”

“Why don’t you let me worry about that?” said the Doctor. “Don’t go planning my breakfast from Detroit.”

Once they had hung up the doctor exhaled noisily, and Esther dragged out suitcases to begin packing for the trip to Indianapolis the next day. She was still packing when Ben walked into the room, with Kim behind him. Having temporarily forgotten Indianapolis, Ben froze at the sight of the luggage. She really is mad, he told himself. This time she means it.

And then Esther looked up. Now Esther, without glasses, can’t see from here to there, and instead of recognizing Kim, she saw only a dim form. “Ben!” she cried. “Ben! That little boy behind you! He looks like—he looks just like—” And then she shrieked, “Kimmy!”

Benjy followed and gave his mother a hug, and Susie, in Jane’s arms, straight-armed her mother and gave her a look that said, “I know I’ve seen you some place, and if it’s true you’re my mother, why don’t you stick around once in a while?”

Esther began to cry, and Ben knelt to explain to his bewildered sons that women are funny because they cry when they’re happy. “I’ll explain the rest of it to you when you’re older,” he said, and Esther laughed through her tears.

The children stayed with them from then on, through Indianapolis, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and the final engagement at the Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas. I never got to hear about the trials and tribulations in those last four cities. There was a smatter of information, such as that they opened in Cleveland the day after the Indians lost the World Series. The street lamps were draped in black, the citizens wore arm bands, and Esther’s show was preceded in the theatre by a newsreel showing the final game, which put the audience in a state of coma. But whatever happened after the children’s arrival, Esther ceased her threats to go home, and the rest of the troupe breathed a collective sigh, and finally, dared to unpack.

By the time we got through talking about Detroit and the Great Reunion, the studio press agent was consulting his watch so often he looked as though he’d developed a tic.

He cleared his throat. “Well—actually, I’m supposed to be covering a preview tonight. And it’s eight-thirty now.”

“Fie on you,” said Esther. “We haven’t even finished dinner. We haven’t even finished Detroit.”

The press agent, pinned between two chores with Father Time hanging over his head like an ax, smiled weakly. So I glanced at my notebook, which was swelling with notes.

“Offhand,” I said, “I figure I have enough for a story.”

“But you haven’t heard,” said Esther, “about Susie’s birthday party and how she stuck her fist into the cake icing and rubbed it on the hotel’s green velvet chair. And about how we now own a green velvet chair that we don’t know what to do with.”

“And the refrigerator I bought in Atlantic City,” said Ben. “It cost $154 and by the time I’d F.O.B.’d it all over the country it was worth $1000.”

The press agent looked at me like a beaver caught in a trap. “You know how they are,” he pleaded. “Give them their heads and they’ll go on all night. We’ll be having breakfast by the time they get you to Las Vegas.”

“Tell you what,” I said. “Ben wants to write a book about this, so I’ll split and leave the last few cities to him. Besides, five million people read MODERN SCREEN every month, so that leaves 155 million for Ben.”

“He’ll never write it,” insisted Esther.

“I’m not complaining,” I assured her.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE APRIL 1955