Jack Lemmon:

Newcomer Jack Lemmon is supremely unusual in the world of Hollywood in that he does not look like an actor. Other film actors find the fact difficult to hide or difficult to prove, but nonetheless, one and all, they need haircuts, they affect a raised eyebrow or at the very least, they wear a scarf under a white shirt in the warmest weather.

Jack Lemmon, on the other hand, looks like a young man in his mid-twenties, possibly from Boston, possibly from Harvard. He looks as though he might be married, happily. He looks suburban. His suits are well-tailored with a Brooks Brothers cut. His pug nose has the tilt to put him out of the running as a Barrymore, but to make him suspiciously Ivy League. He looks for all the world like the rising young executive of a very old, very staid paper company.

He is all these things except the last, and therefore it is remarkable that he is a movie star.

From such a description he might seem to be a misfit in Hollywood. On the contrary, he is as welcome as the flowers in May. For one thing; he knows his craft. For another, he gives no sign of being at all like the Hollywood conception of the Ivy Leaguer. There is no stuffiness nor snobbishness in Jack Lemmon. In his speech there is not a trace of a Boston-Harvard accent which could send Hollywood citizens scurrying for the safety of their own coteries.

Jack arrived unsung from New York in the spring of 1953 and promptly went to work in a delightful role opposite Judy Holliday in It Should Happen To You. During the following months Mr. Lemmon made only a small splash. Although New Yorkers knew him well from radio, television and Broadway, to Hollywood he was an unknown quantity. He seemed to be an unassuming lad, medium height, medium build, medium coloring (brown eyes, brown hair) with a boyish voice.

When It Should Happen To You was previewed, reviewers across the nation mentioned Jack with adjectives ranging from pleasant to laudatory, and hailed the medium young man as a rare find for the screen. They said he had a warm and appealing personality, that he was deft as all get out at comedy, that he was an actor of conviction and that the screen should see more of him.

The recognition of his talent naturally pleased Columbia Pictures, who had put him under contract after his debut performance on Broadway in Room Service. Noting the acclaim for Jack’s comedy, they assigned him to Three For The Show with Betty Grable (comedy role) and scheduled him for Phffft! (comedy role).

Jack reacted in two ways. He was happy as a clam to have hit Holly wood’s big time, but he was worried by the thought that he might be typed as a comedian. He knew, he said, that he could do other things, that he wanted to do all kinds of roles and that he hoped he’d have the chance.

There’s a valid reason why Lemmon has been thrice cast in comedies, besides the fact that he is adept at this most difficult of arts. Personally, he is a very amusing young man. He speaks with a flair for phrase and a humorous twist.

He acknowledges Boston as his birthplace but adds that the family moved to Newton (seven miles away) when he was a small child. He claims his parents were a rather soft touch for their only child, endeavoring to give him piano lessons and all the things they felt were advantages and he felt were extremely dreary projects. There were his days at Phillips Andover Academy, prepping for either Yale or Harvard. This kind of thing was made possible by his father’s success in the bakery business plus the invention of a machine that perpetually produces doughnuts. Jack can tell you all about doughnuts, how they are best made, and even the why of the hole in the middle, an interest which shows him to be a grateful young man who knows whence his blessings came. He has been unusually lucky, he figures, for he not only had all this, but when he took his V-12 tests at Andover he was assigned to a Naval Reserve unit at Harvard—ten minutes from home. Recalling those three years at Harvard he twinkles at the mention of the nearby Wellesley girls, gives a pitch for the pulchritude at Pine Manor, omits the fact that he was president of the Hasty Pudding Club and elaborates on his opinion that at college he Was a horror. “I must have been a stupid little jerk. I thought I was a big wheel on campus and it’s interesting to me now that when I meet guys who were in my class I find them tremendously stimulating and not meatballs at all.”

After three years of Navy training at Harvard he was assigned to a desk job in Boston’s Fargo Building as Ensign Jack Lemmon, traffic officer. He spent his days picking up a phone and announcing meekly: “Lemmon. Jeeps.”

A few months of this and he was assigned to the aircraft carrier Lake Champlain. During his few weeks aboard Jack had two hours and twenty-two minutes at sea—a trip from Norfolk to Newport News—and it turned into a fiasco worthy of a movie (comedy role). The Navy had the misunderstanding that Jack was a communications man and assigned him as communications officer of the big ship. This job ordinarily would have been held by a full lieutenant at. least, but the war was over and the ship was being de-activated as quickly as possible. So Ensign Lemmon set happily to work taking inventories and figuratively chucking overboard everything he could find—including the code books.

The Lake Champlain had no sooner put to sea on Ensign Lemmon’s sole sea voyage than a huge tanker was sighted, bearing down upon her. The tanker, according to Jack, was signaling by semaphore, by every flag the Navy had ever seen and by lights flashing so frantically that the hulk looked more like a Times Square sign. The captain on the bridge of the Lake Champlain leaned over the side and roared downwind to his communications officer. “Lemmon! What are they saying?”

Ensign Lemmon, who didn’t know an S.O.S. from a Full Speed Ahead, didn’t have a clue. And when he asked a Chief standing at his side the man said, “I’ve never seen such a signal in my twenty-two years in the Navy. And we can’t find out. You’ve logged all the books over, sir.”

“It must mean something!” squeaked Ensign Lemmon.

“I can guess,” said the Chief. “I’d say she’s out of control—that her right rear screw’s broken, maybe. In which case they’ve got the right of way, sir.”

It was something, better than nothing, and so Ensign Lemmon howled the conjecture up to the Captain who shouted, “Great balls of fire!” and began spewing orders. Within minutes the two ships passed each other, missing contact by mere inches.

It turned out that the Chief’s guess had been correct to the letter, and Ensign Lemmon was given a recommendation and shortly sent back to Boston where he took his leave of the U. S. Navy.

He borrowed $300 from his father. Lemmon, Sr., wanted his son to join him in business, but Jack had set his sights on show business. The family was pleased, having been sprinkled with entertainers (before the bakeries Jack’s father had done a soft shoe routine on the stage and his mother was a singer) but apprehensive about Jack’s chances in a world where there are 2000 men for every job.

The $300 was soon gone, spent for room and meals while the young genius composed show tunes that didn’t sell and scores for Broadway musicals that never opened. Finally he got a job playing piano in an obscure nightclub. For a pittance he played all the tunes he’d ever written, and the customers growled through the smoke, “Hey, bud, play something we know!”

Later he got another job in another nightclub, this one owned by another Harvard graduate who fraternally allowed Jack to spread his wings. Mr. Lemmon did seven shows a day, writing, directing, producing and emceeing them and never repeating once. “A young actor needs a place in his beginning where he can smell something awful, but he learns.” In the early months in New York there were many jobs like these. Jack lived in a succession of cold water flats. One, priced at $2.50 per week, was on the top floor of a seven-floor walk-up, over a delicatessen. The rising odors, captured for eternity in Jack’s apartment, were more than made up for by Isaac, the delicatessen owner, who knew a hungry boy when he saw one. He donated sundry fat sandwiches without thought of reward.

There was a flat which boasted seven rooms, a piano and a library of 1000 volumes. They were all pocket size pulps, to be sure, but it was a library nonetheless, and it was in one of the two rooms Jack used. The other five were closed off because of mice.

There was the classier flat at $5 a week. The door had no latch and no doorknob, just a padlock.

There was the attic flat with a skylight in lieu of windows, a nest for which Jack paid a flat $3 weekly. The phone was in the basement and tenants who wanted phone service were asked an additional twenty-five cents. For this weekly sum, when they were phoned, the landlady bellowed their names up the stairs. Jack was the only one who couldn’t afford the quarter, so whenever there was silence following the phone’s ring he plummeted down six flights of stairs in an effort to get there before Signora Graciana had hung up.

At this rate there wasn’t much hope of paying back Lemmon, Sr., his three hundred dollars, but Jack had learned that his father had once borrowed $1000 from his father and it took him six years to return it. This happy bit of news relieved his conscience and allowed him to plod on.

Eventually he did this, beginning with parts in radio soap operas and graduating to television, appearing in more than 500 shows, not including the three TV series which he produced and starred in.

He tells it all in high good humor. But Jack Lemmon is a great deal more than amusing. He has the rare sensitivity of the dreamer, he has quick intelligence and underneath the fun he is quite serious.

Some of this stems from his father, a man seemingly steeped in industry, who once said, “The first day I cease to find romance in a loaf of bread I’m going to get out of this business.” Jack agrees with his father. He recalls with considerable sentiment and nostalgia the summer home in New Hampshire he and his dad built with their own hands. And he remembers his years at Phillips Andover when he wanted more than anything else to be a painter. Before he was sixteen, The Atlantic Monthly carried an article written by young Lemmon’s art teacher, Pat Morgan, who used Jack as a model for his story on the dreams and thoughts of a youngster who envisioned painting as his life’s work. Pat Morgan and his wife made a deep impression on Jack, and he still treasures the stolen hours spent with them in their home “because when I was in their house they were not my teachers but my mentors, and they treated me as a person with my own thoughts and needs.”

Jack was a serious young man. After his discharge from the Navy he went back to Harvard for a year’s course in physics, in order to get his degree. And he was serious about his music and his acting. When he first went to New York—the first night he was there—he walked all night through its streets and along its rivers, dreaming of his future in the city. It was dawn when he walked down Shubert Alley and saw the old sign with its peeling paint, “Through these portals pass the great and ungreat of show business.” To Jack it was a personal challenge.

“It was the first time I’d been away from family and friends—the people who used to applaud my efforts whether or not they were any good. And now that strangers didn’t rise to the bait all the time I began to realize I was out of the parlor and on my own. I did a lot of growing up.”

Lemmon watches other people, their words, gestures and deeds, their pattern of behavior. He speaks of being an actor, and of being a star. “There’s no connection between the two. Wanting to be a star is a phase you go through. When things begin to move, you’re too busy with craft, with worrying about your ability, to be impressed by autograph seekers. All your

values change. When I walked along the river at night I promised myself one thing if I ever made the grade—clothes. Now ’m too busy even to think about clothes.”

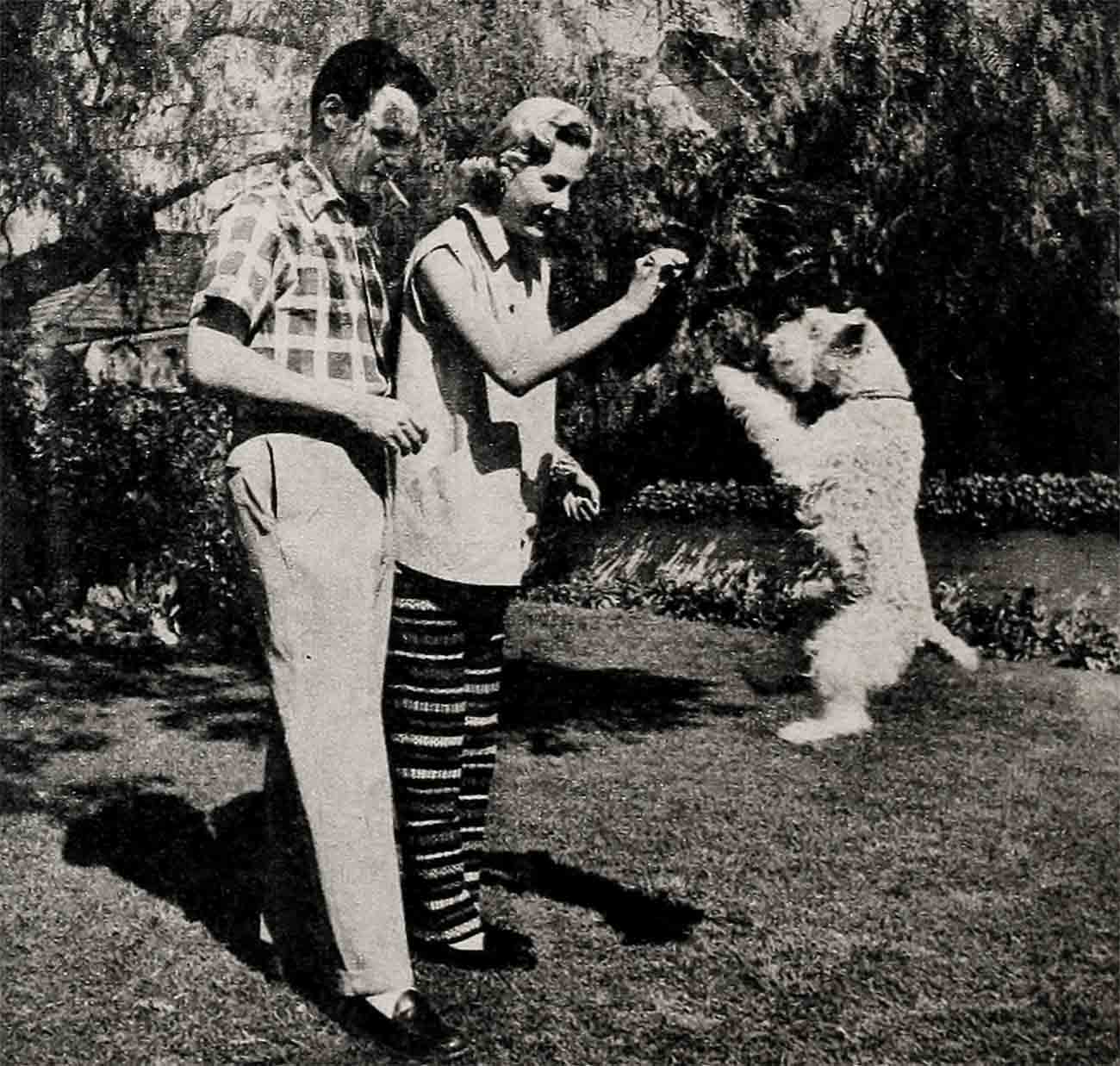

He is serious, and after four years still excited, about his marriage to Cynthia Stone of Peoria, Illinois. He and Cynthia met when they had roles in an off-Broadway play, and married two years later, disregarding the fact they couldn’t afford it. Just now, Cynthia is at home with Christopher Boyd Lemmon. He was a little late in his arrival, putting his prospective parents into a dither. Jack was working in Phffft! and every time the telephone on the set rang, he all but knocked over the rest of the cast and crew to answer it. But he finished the picture and was sitting calmly at home when the baby got. ready for his appearance at Cedars of Lebanon, June 22, 1954.

Of Cynthia Jack says. “She can do anything and do it well. If she gives a party or decorates a home or visits the kids in the Children’s Hospital or acts in a play, she does it beautifully. She has innate taste. I think the reason we’re so happy is that we’re on the same level of communication.”

Lemmon thinks and philosophizes about people. He understands himself rather well. He can even explain the attraction show business has for him. “The first thing I remember is our move from Boston to Newton when I was about four years old. The woman next door wanted me to play with her son—his name was Billy Tyler, I remember—and it’s all so clear to me that I can still feel the embarrassment and shyness that came over me. I didn’t want to play with the kid because I felt I was a complete stranger. I think that’s why I’m in show business—I feel the need for acceptance. My parents made me feel loved and wanted, of course, but it might be because I was an only child that I wanted acceptance on a large scale.”

It would seem he is going to get that acceptance—and on a very large scale. He will capture his audience with his light, comic touch and then, when he is given the opportunity to prove that his acting ability covers the same range as his conversation—from the ridiculous to the sublime—he will certainly America’s favorites.

Jack’s dabbling in paints and pianos, his charming singing voice, his directing and producing of TV shows, his talent for musical composition, all make him a Jack-of-all-trades. But he is master of at least one. Whether or not he looks the part, he is an actor.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955