Is It Bad To Be Good?—Debbie Reynolds

A few months ago, the spectators at an industrial league baseball game in California’s San Fernando Valley saw that one of the pitchers was blowing up. And they knew why. Seated among the crowd in the crude, wooden stand behind home plate was a young girl who was riding him expertly. “What’s the matter?” she would call. “Just because you’re cute can’t you put the ball over?”

Ever since she had arrived, in jeans and light pullover, people had turned to each other and speculated about her identity. In her attire and manner she was like any of a dozen other girls present, yet everyone agreed that her face was familiar—they had seen her somewhere before. The girl resembled the third baseman on one of the teams, and it was apparent that she was rooting for his side. Several innings passed before everybody found out who she was. Word got around after some old men, retired gaffers who came daily to smoke their pipes and watch the games, were heard speaking to her. “Been watchin’ ya, Debbie, while you were away,” they said. “Been seein’ how you been doin’ in the movies.”

Debbie Reynolds, after a round of personal appearances through South America and a season of playing summer theatre in the middlewest and southwest, was back home in Burbank and again fitting happily into the ways of the community she loved.

“Oh, you robber!” she screamed at the umpire, as he called a questionable strike on her brother Bill, who was playing for the Burbank Blues against the Blanchard Lumber Nine.

“That’s the old Debbie,” murmured one of the oldsters approvingly. “That’s tellin’ him. You hain’t forgot your baseball.”

Debbie “hain’t forgot” more than her baseball. She “hain’t forgot” her old friends, her Girl Scout activities, the taste of a double root beer float at Bob’s Drive-In around the corner from her home, her mother’s sewing room where she always got in her mother’s way—and still does—and a thousand and one other warm elements of her girlhood. Riding high in glamourland, where the pitfalls, both social and professional, are as deep as the heights are dizzy, she is so heart-tied to the old and beloved associations of her youth that new ones—the kind that so often trip up a young star—have no undue attraction for her.

As one of her old school friends puts it: “Debbie hasn’t pulled a ‘boo-boo’ yet and she isn’t going to. Hollywood isn’t going to get her because Burbank’s got her!” Debbie hasn’t sworn off Hollywood’s social circles; her life just isn’t confined to those orbits. She had a well rounded, satisfactory life before she ever got into the movies. She gets a kick out of the after-premiére parties, the gay Bel Air affairs and the Strip-club shindigs she sometimes attends, but she walks and talks best to the tempo of the life she was born into. The real Debbie Reynolds is the girl who spent her last vacation exactly as she used to spend vacations when she was a school girl; she slept a low, cleaned the yard, helped her father paint the back fence, got whacked at tennis by everybody and put in a week as a counselor up at the Girl Scout Camp in Fraser, California.

She was at Ciro’s when Peggy Lee was singing there. She is crazy about Peggy’s song technique. She spent a lot more nights at the Melody, an unpublicized jazz grotto in Burbank, where the musicians turn real “cat” while the bopster-patrons, Debbie included, sit swaying ecstatically with the beat and whispering, “Go! Go! Go!”

It is true that she was squired by such Hollywood men as Dick Anderson, Hugh O’Brien and Tab Hunter. But much more often her escorts were Paul Lillard and Danny Sites—together at that—a couple of Korean war veterans who love Debbie like brothers. Paul is the soldier-fan who wrote such interesting letters to Debbie and her folks from the battlefront that they invited him to visit them when he came back. Now, they have informally adopted him into the family. Danny has lived near Debbie since they were both children. When he was leaving for Korea two years ago, Debbie gave him Paul’s address. The boys not only met but became fast friends. Now that they are back they are writing a book about their war experiences—much to Debbie’s discomfiture, sometimes.

“I often wonder if they know I’m with them,” she complains. “Each one carries a little pad and pencil, and every few minutes one of them thinks of something for the book. Out comes the note pad and they scribble away like mad. If I want to dance they offer to find someone for me!”

Like the rest of Debbie’s friends, Paul and Danny see her as.a sweet, bright girl, not as a movie star, and they aim to keep seeing her that way. They are not a bit bashful about straightening her out when they think she needs it. Like any girl, especially one with an inborn gift for mimicry, Debbie will sometimes unconsciously take on the color and manner of people around her; she’ll return from the studio, for instance, acting a bit like the grande artiste. When this happens the kids go to work. They look at her coldly and ask, “What’s with you?” And before she can figure out what they mean, they add, “So shut up and sit down!” Then Debbie knows she has been “glorifying.”

Her mother, Mrs. Maxene Reynolds, takes a hand at this, too. Not long ago, Debbie came home after a fashionable reception attended by many of Hollywood’s English set and began talking like a female David Niven. After she had “rawthered” all around the place for a few minutes Mrs. Reynolds interrupted to ask Debbie to please swallow.

“Swallow what?” asked Debbie.

“All that mush you’ve got in your mouth,” her mother told her.

Debbie swallowed and. talked straight again. She is grateful to her mother and the others for jerking her back into character every time she starts riding a high horse.

“If ever I get away from being just me,” she says, “I’d be sure to wake up some day and hate the person I was pretending to be. I spent years, from the time I was nine, developing the friends I have around home. I’ve got all those years invested in them, and they’ll keep me happy for the rest of my life. That’s my way of being rich and secure. They make me content to come home when otherwise, well—who knows what would happen, where and how I would seek to express myself if I didn’t have them?”

In Hollywood, where the next flower, you pick up can sting you, it isn’t bad to have this sort of background, this incentive to settle for the good and not seek the overgay.

Debbie is still “investing” in friendship. Between her South American tour and the summer theatre work, last season, she had just five days in Hollywood in which to study scripts, learn the musical score of her first show, Best Foot Forward, and be fitted for costumes, Any other star would automatically have gone into seclusion under the stress of a rugged schedule like that. Not Debbie. She not only called and talked to her old pals, she took a day off to give a baby shower in her home for one of her three closest friends, Diana Higley, now Mrs. Barry Cheek. The other two members of this high school foursome, Barbara Christie and Jeanette Johnson, suggested that Debbie might not have the time to spare. “Of course!” responded Debbie. “Diane’s first baby? Why nothing could be more important than that!”

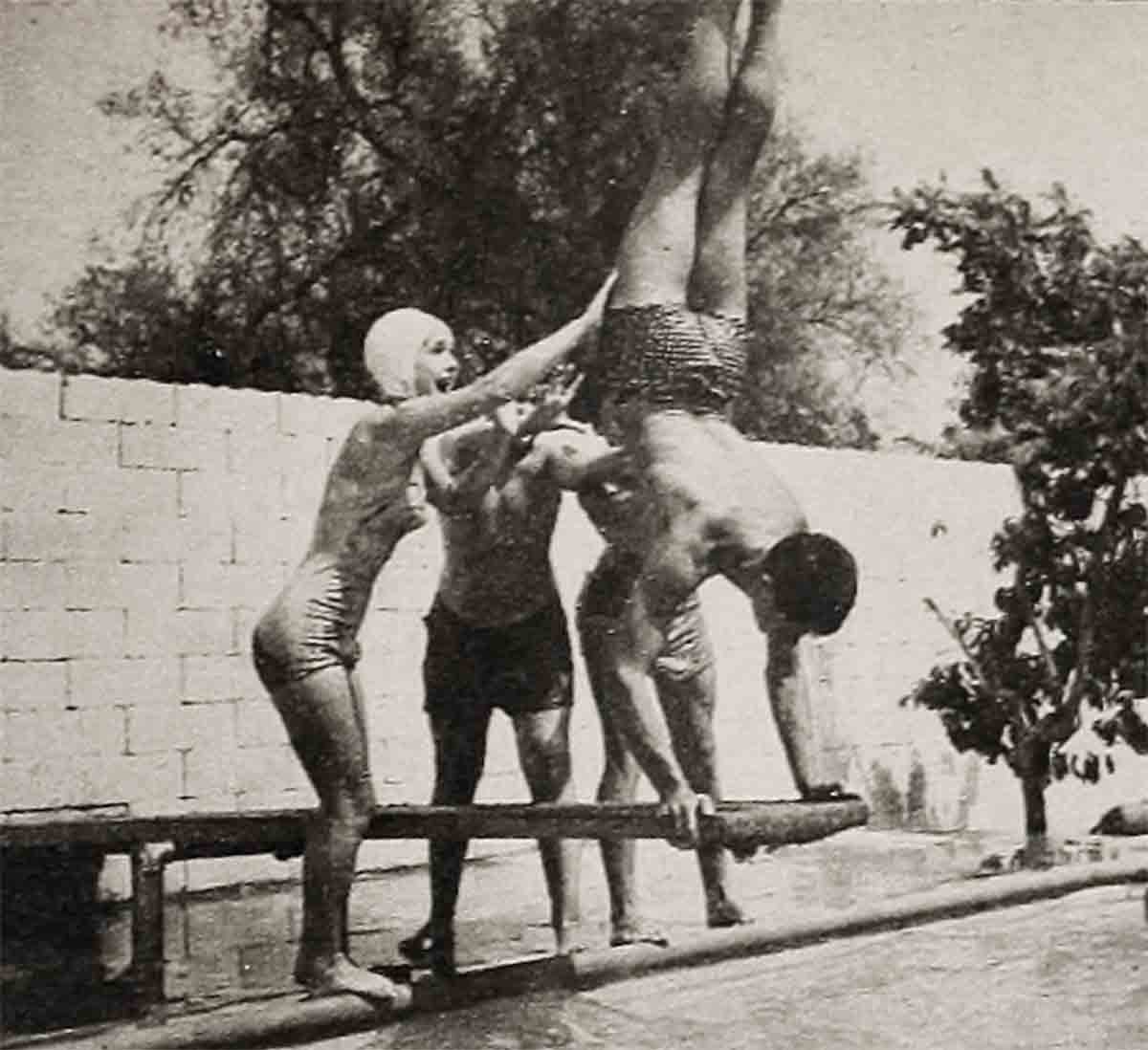

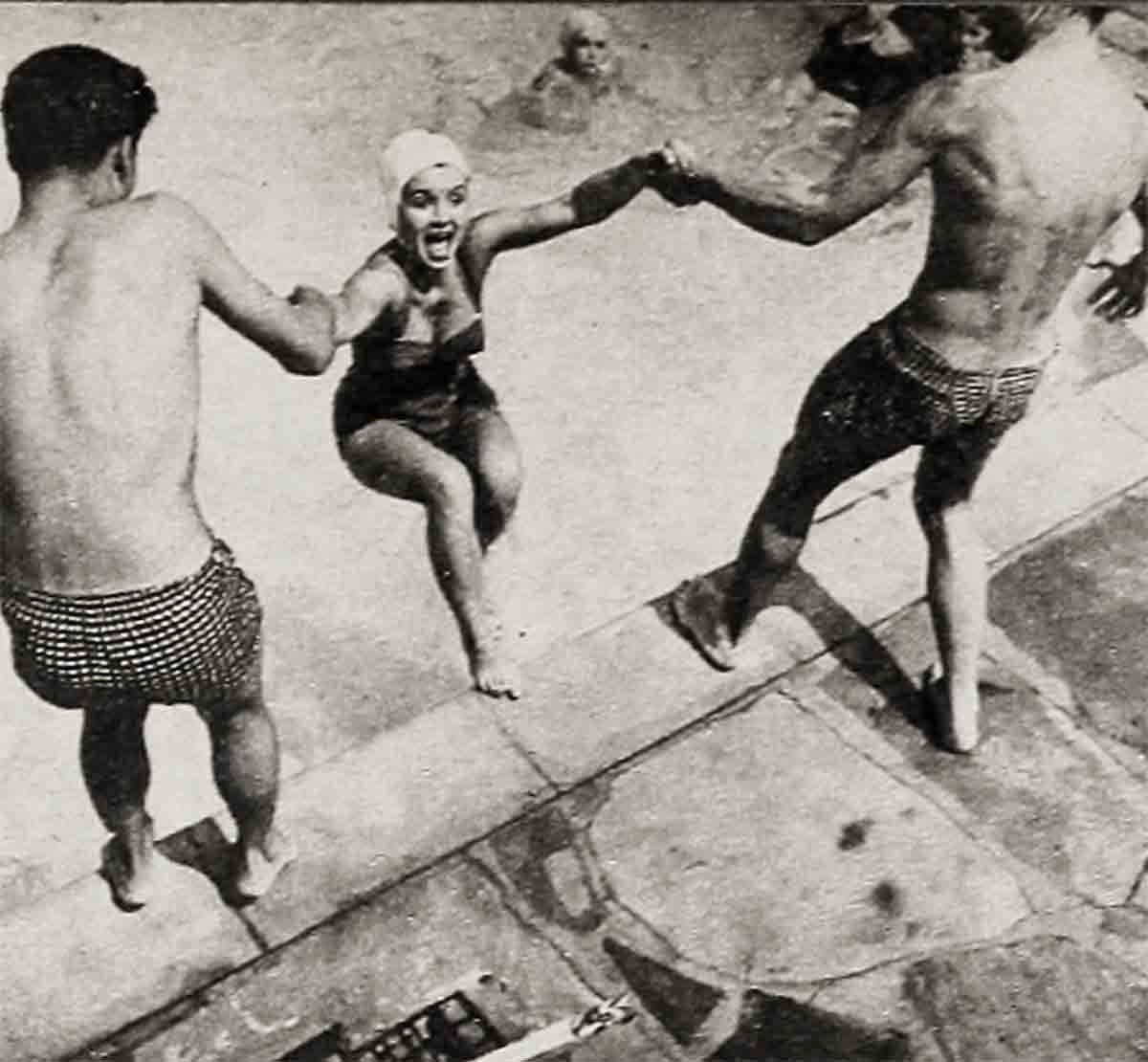

That wasn’t all. Debbie had just returned from playing Hinsdale, Illinois and Dallas, Texas, when Diane went into the hospital to have her baby. Her three pals got hold of her husband, Barry, took him to Debbie’s home, fed him and tried to talk him out of his worry. Three times, they pulled him out of the pool into which he kept falling while he wandered around the place in his distraction. “This boy is positively the end!” the girls agreed, and kept a sharp eye on him until the baby was born.

Debbie keeps her appointments straight by using a system unlike any other star’s. She has no book. She just uses the annual calendar issued by the Girl Scouts of America. It hangs on the wall of her room. Whenever she makes an appointment, she jots down a note about it in and around the particular date on the calendar. Noodled between the numbers in the month of July, for instance, are fragments like “HOB Tennis” (tennis with Hugh O’Brien), “P. O.” (piano lessons), “PR-TH” (attend premiere with Tab Hunter) and “B” (bowling with Paul and Danny).

When Debbie attends a premiére she is both star and fan, of course. She drives up in style, makes her little speech over the public address system for the benefit of the crowd, enters the theatre—and then sneaks back out to a convenient corner where she can watch the other stars arrive. That’s exactly the program and Tab Hunter followed when he took her to the Stalag 17 premiére in his salmon-colored convertible.

After the show he checked his money and told Debbie they could have as wild a time as could be squeezed out of two dollars. It turned out that they only needed forty cents for a root beer float and a lemonade in a drive-in.

When Debbie is with kids she grew up with, being herself comes easy. With others she sometimes has to work at it. And she does. She can’t stand the strangeness that falls like a damp cloak between her and people who are overpowered by her professional identity.

“The most important things about the kids I know is that they are down to earth, yet very reasonable about other people’s lives. If you are wealthy, that’s okay with them, just so you don’t pin the dollar sign on your sleeve. They know I’m doing well in the movies, but when they hear about my getting up at five o’clock, morning after morning, to get to the studio, and not getting back until way after dinner, they begin to think I’m crazy.

“ ‘Hey, that’s not like you,’ they say. ‘You’re working too hard, girl. Slow up.’ ”

When she went to Girl Scout camp, Debbie had a different problem. She had never met the seventeen-year-olds placed in her charge and her first two days with them didn’t go well. She knew they couldn’t accept her as a real person. She was a movie star and they insisted on being overawed about it. They were shy; none of them ever cut up and whatever they were asked to do, they did without any back talk.

That was bad. Debbie felt that she was not only spoiling their vacation, but her own as well. She quietly discussed with her mother, who had come along, the advisability of slipping away and leaving the girls free to enjoy themselves without the distraction of her presence. But her mother urged her to stay for another day, anyway.

Debbie worked hard at it, kidding the girls, poking fun at herself, asking their advice on a whole series of subjects including diet, make-up, etiquette and boys. When one kid tentatively suggested that Debbie didn’t eat enough, she felt she was getting somewhere with them. When, by nightfall, another girl let something Slip about Debbie’s being too skinny, she knew the girls were getting to be themselves again and everything was going to be all right. For the rest of the week they all had a hilarious time together. The last night the kids staged a gag ballet performance for her. They ran around under the stars, tripping over huge blankets they were using as veils. Debbie fell off her cot laughing.

When she got back to Burbank, she got in touch with Jeanette Johnson and they had a conference about a matter that has had them thinking a lot the last few months. Out of the eighty girls in their graduation class at Burbank High, only Jeanette and Debbie are still unmarried. At first they kept asking each other: “What’s the matter with the boys around here?” Now they are beginning to take a more objective view of the situation. “Do you suppose it’s us?” Debbie asked.

“Wouldn’t that be positively the end?” asked Jeanette.

“We better check,” Debbie replied grimly.

That’s what they’ve got a thing about right now.

THE END

—BY JIM NEWTON

(Debbie Reynolds can be seen in MGM’s Give A Girl A Break.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953