I Was An Orphan—Marilyn Monroe

Before I was born, my father was killed in an automobile accident during a business trip to New York City. A short time later, my mother became critically ill, and while I was still too young to know much about what was happening, I became an orphan.

Naturally, that fact has greatly influenced my life. I know that often, in moments of loneliness, it has been the cause of deep personal sadness and even, at times, self-pity. But I also like to think that it is responsible, at least in part, for my having been able to realize my greatest ambition—an acting career.

I don’t like to dwell on the confused and unsettled part of my childhood. When I was orphaned, the court, as is customary in the state of California, appointed a legal guardian for me. At first I lived with the guardian, but because she had a family of her own, it became necessary for me to live with someone else. I don’t suppose I need to remind anyone that the 1930’s were difficult times for everybody.

During the years that I was going through grammar school, I lived with a number of different families all over Los Angeles. I’m not sure, but I believe I went to seven different grade schools. And I always attended the church of the faith of the family I was living with at the time.

I don’t believe that I ever really gave any trouble to the people I lived with. I was a shy little girl, and while I was still very young, I developed a make-believe world for myself. Every afternoon when I took my naps, I would pretend things. One day, I would be a beautiful princess in a tower. Or a boy with a dog. Or a grandmother with snowy white hair. And at night, I would lie and whisper out, ever so softly, the situations that I had heard on the radio before bedtime. I don’t believe that I minded much being alone. In fact, I rather enjoyed it.

I remember a vacant lot that I used to cross on my way home from Bakman Avenue School in North Hollywood. It was just a dirty old lot overgrown with weeds, but from the moment I stepped onto it, it became a magic and private place where I could be all of the people I had been thinking about all day in the classroom. I didn’t need much else to be happy even when I had to live in an orphanage for a couple of years.

When I was about 12, I went to live with the woman who was the greatest influence in my life. Her name was Mrs. Anna Lower, and she was the only person I ever really loved.

Aunt Anna lived in Sawtelle, not far from the Veterans’ Hospital. It wasn’t an elegant neighborhood by any standard. That fall, I started at Emerson Junior High School, and was just at the age when clothes were beginning to be important. I couldn’t help but notice that mine weren’t as pretty or varied as the other girls’. One day, one of my classmates made a comment about the dress I was wearing and I came home crying. I was so self-conscious and miserable that I never wanted to go back to school. Then Aunt Anna started reassuring me, and I began to feel better. “It doesn’t matter if other children make fun of your clothes or where you live,” she told me. “It’s what you are that counts. You just keep being your own self. That’s all that matters.”

At first, I didn’t understand a lot of the things she told me when I was feeling blue. I was too busy being miserable. But I knew that she loved me, and that was a wonderful thing in itself. Most of all, Aunt Anna tried to convince me that there was nothing in life to be afraid of. “Live each day and take things as they come. Face everything, work hard at the things you want to accomplish, and you will have nothing to fear,” she would say. “Maybe you don’t think so now, but you will find out later that I’m right.”

And I have. I can’t remember Aunt Anna without thinking how fortunate I was to have had her wonderful philosophy as an influence in my life. She was in her 60’s when I first went to live with her, but she was still a most attractive woman with great dignity and inner reserve. She was most tolerant of my big ambition of being an actress.

In junior high school, I was completely movie-struck. I used to go see movies I liked three or four times when I could afford it. Ginger Rogers was my favorite star. A girl who lived across the street subscribed to several of the fan magazines and she would give me all of the pictures of Ginger. I had several dozen of her portraits pinned up around my room.

I remember saying to one of the families that I lived with that I’d like to be an actress like Ginger. “You’d better get that silly idea out of your head,” I was told quickly. Aunt Anna didn’t think it was silly. In fact, she encouraged me to read aloud to her. I was probably pretty hammy but she never let me know it.

I lived with Aunt Anna until I finished my first year in high school, and then, when she was called East, I went to live with a family in the San Fernando Valley. At Van Nuys High School, I tried out for several of the school plays, but I was too scared even to do a decent reading. I never got a part.

Just about a week after my 16th birthday, I went back to spend the summer vacation with Aunt Anna, and it seemed almost as if I hadn’t been away. That summer I got married. I know now that I was much too young for marriage, but at the time, it seemed sensible enough. My husband, whom I had met through my guardian, was six years my senior, and we liked one another.

I went back to Van Nuys High School that fall, and was somewhat of a curiosity to the other girls in my class. “She’s married!” they would say, in an awed tone of voice, whenever they introduced me to someone new.

High school isn’t exactly the place for a married woman, and I was very happy when I graduated the following June. None of my classes had meant much to me.

Because of our youth, our marriage did not have much chance for success. Shortly after I graduated, we were divorced, and I went back to live with Aunt Anna. I always felt that I had a home with her. She made me feel that way. I remember that summer I started writing a long narrative poem based on the theme that “Time Heals Everything.” It was three pages long when I finally decided that it could go on forever.

Fortunately, I began to get work as a model soon after I registered with several of the top agencies in Hollywood. Within a few months, I had been photographed by Andre De Diennes, Willinger, Tom Kelly, and most of the leading glamor photographers, and it was not long before I received a screen test at 20th Century-Fox on the strength of these photographs.

I was sitting on top of the world when they told me at the studio that my test was a great success and offered me a long-term contract. Aunt Anna was thrilled for me. It was simply too wonderful to be true.

And that is the way it turned out. If you saw Scudda-Hoo, Scudda-Hay, and were watching June Haver closely, you might have seen a 67-second closeup of my back during one of the dance numbers. 20th didn’t think enough of my back to pick up my option, and my dream came tumbling down as quickly as it had been erected.

I learned something from that experience. When I first was signed by 20th, I decided that at last I could begin affording some of the things I had always wanted. I began taking dramatic lessons (which was the most sensible investment I ever have made), and I bought a beautiful radio-phonograph combination on the installment plan (which was not). When I began working at Fox, I also moved into a small apartment near the studio, And I bought a used car.

Suddenly, I found that I was unable to make ends meet. One day when I got home, I found a man waiting to pick up my radio-phonograph. I was almost heartbroken as I watched him carry it away, and to this day I have yet to see a more beautiful cabinet or player. Then, a few weeks later, I had to give up my apartment. I didn’t feel right about moving back in with Aunt Anna, so I got a room at the Studio Club. Under no circumstances, I promised myself, would I give up my dramatic lessons. I had been studying for about five months with Natasha Lytess, who is now the dramatic coach at 20th, and I felt I was making real progress.

So I went back to modeling. But despite the fact that I was working hard as a model, I simply wasn’t earning enough money to pay my bills. I’d often get four or five weeks behind in rent at the Studio Club, and I don’t know what Id have done if they had asked me to move out. For about a year, I was living on the two meals they served each day—breakfast and dinner.

I never will forget the morning I went out to the curb where I had parked my jalopy and found that it had vanished. I went back inside and called the Hollywood Police station and dinner.

I never will forget the morning I went out to the curb where I had parked my jalopy and found that it had vanished. I went back inside and called the Hollywood Police station and reported that my car had been stolen. They called me back about it only a couple of hours later.

“Sorry, Miss Monroe,” the desk sergeant told me. “Your car wasn’t stolen. The finance company picked it up last night because there are two payments due.”

I finally managed to bail it out, and somehow I managed to keep up my dramatic lessons. To make matters worse, Aunt Anna passed away that summer, and I was left without anyone to take my I was miserable.

They one day, Columbia called me and offered me a test, and suddenly I was caught up in “the big plans” the studio had for my career. I was signed to a longterm contract again and immediately given a role in a B musical they were casting. I worked nine days. And then I waited for something else to happen. Came option time and again I was unemployed.

This time, it was a dress shop that got me into hot water. Shortly after Columbia signed me, this shop sent a representative over to the Studio Club to see me, and offer me a deal.

“Miss Monroe,” he said, “our shop dresses a good many of the young starlets in Hollywood. We would like you to feel at liberty to come in and select a wardrobe, and take as long as you like to pay. We understand how difficult it is for a young player just starting out to manage at first, and we would like to be of service to you by setting up this credit for you.”

I have never been clothes crazy. Aunt Anna’s good sense cured me of that. But I thought the man’s offer made sense, so I went in and bought some clothes. Nothing fancy. Just two serviceable suits, a black some shoes, and some hosiery. About two hundred dollars worth in all. But when Columbia dropped my contract, the store’s sweet tone disappeared, and a few months later I walked out in front of the Studio Club one morning to find a tow truck hauling my car away again. This time, it was a collection agency picking it up as collateral for the money I owed the dress shop. Once again I had to scratch enough together to bail it out.

I went back to modeling to keep eating, and I worked harder than ever at my dramatic lessons. It was several months before I got my next opportunity to try out for another movie role . . . this time a small bit in the Marx Brothers’ Love Happy. Groucho chased me across a room and I was on the screen less than 60 seconds, but. I got five weeks work out of the part by going on the P. A. tour, which promoted the film in eight major cities. I felt guilty about appearing on the stage when I had such an insignificant role in the film, but the people in the audiences didn’t seem to care.

Shortly after I returned to Hollywood, I received a call from 20th’s casting office. “Do you dance?” they asked. “Sure,” I said, even though I didn’t know any fancy steps. I went out to see them, and ended up getting five weeks work in Ticket to Tomahawk.

While I was working at 20th, Lucille Ryman, the head of the talent department at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, told me that I ought to see John Huston. I went over that afternoon and Mr. Huston told me about The Asphalt Jungle. “You’re the type,” he said. “But I don’t know whether you can do the part.” I asked him to let me study the part and then read it for him.

I studied the script, and when I went back to see Mr. Huston later in the week, I felt confident that I could play the role. Mr. Huston was wonderful when I read for him. I was scared stiff, but he did everything he could to put me at ease. I got the part. And as I walked out of his office, I was terribly thankful that I had kept up with my dramatic lessons, even when things were tough, because they had paid off when the chips were down.

Shortly after I finished The Asphalt Jungle, my first really substantial role, I received another call from 20th to read for All About Eve. I met Joseph Mankiewicez, the director, who gave me not only the part of Miss Casswell, but great encouragement and help. It isn’t a big part, but it is a striking character I play. When Mr. Zanuck saw the first day’s rushes, he offered me a new seven-year contract.

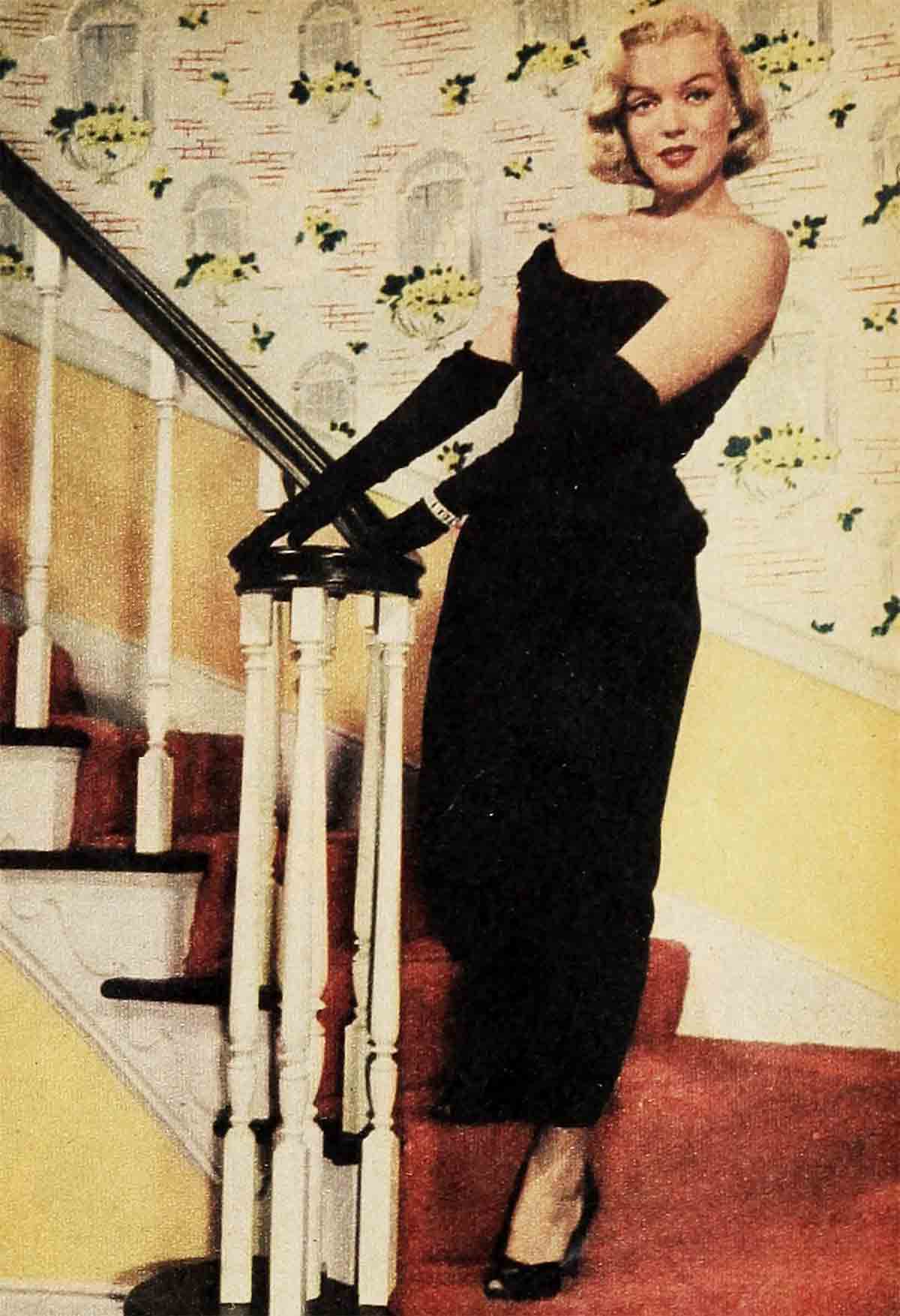

It’s a great joy for me to realize these days that my childhood ambition wasn’t completely foolish. I still have a lot to learn, but I’m very grateful that I was able to sustain that ambition and profit from the mistakes I have made in my life. I think I have learned a lot. For instance, I do not own a vast unpaid-for wardrobe. The other day, I splurged on two black dresses, but I paid cash for them both. Although I love music, I do not own a radio-phonograph, in cooperation with a finance company. Mine is an inexpensive portable covered in imitation leather, and it is mine, all mine. I own a Pontiac coupe, not a Cadillac, and I do not owe a single bill which will not be paid before option time rolls around.

And I have learned, too, as Aunt Anna used to tell me, that there is nothing to fear if you face life and work hard at the things you want to achieve. Once I wouldn’t have dared to hope for what I wanted most. Now I want to work towards being a really fine actress. Being a good actress won’t quite do. I want to be a fine actress, and I’d hate to settle for less. As a matter of fact, and for the record, I won’t.

THE END

—BY MARILYN MONROE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1951

No Comments