How Long Can Burton Hold Liz And His Liquor, Too?

Ten quotations, statements and actions at different times and places, all of them adding up to a pattern of self-destruction:

BEFORE THE ROMAN SCANDALS: Richard Burton says, “If anything happens to Sybil and the kids, l’ll become an absolute alcoholic. I’ll go to pieces completely… completely.”

JUNE 6, 1963: Jerry Tallmer writes: “There is one symptom: Burton is drinking more than ever before in his life. ‘He is under unbelievable tension,’ said a returned veteran of the Nile campaign. ‘In that hotel room in London, each now, I believe, wanting to be out of it, but each also wanting to be the rejected one . . . The whole thing is a fantastic study in masochism. And the greatest masochists of all are Elizabeth and Richard because they are deter- mined not to salvage anything.”

DECEMBER, 1963: Doug Brewer recalls Burton’s actions during the filming of ‘‘The V.I.P.s”: ‘‘Normally merely a ‘good drinker,’. . . he was now beginning to belt down the booze too fast and often.”

APRIL 26, 1963: ‘‘Cleo” writer-director Joe Mankiewicz is quoted as saying: ‘‘Show a Welshman one thousand exits, one of which is marked self-destruction, and he will go right through that door.”

AUGUST, 1963: Actor Stanley Baker, Burton’s old friend, says flatly: “Elizabeth Taylor and Burton are destroying each other.” He said it as a sad truth, not criticizing.

DECEMBER 20, 1963: Richard Burton, confronted by Liz after he’s been out drinking in Puerto Vallarta with writer Budd Schulberg, snaps at her, “If you don’t watch out, l’ll marry him.”

DECEMBER 22, 1963: Sheilah Graham asserts: “I have the feeling that Richard Burton is a reluctant bridegroom. He did not want a divorce from his wife, no matter what Liz Taylor says. Of course, he didn’t want to give up Elizabeth, either. I believe he is a very depressed and unhappy man…”

JANUARY, 1964: Elizabeth Taylor, watching Burton as he was drinking, digs: ‘l’ve been sitting here for half an hour, just waiting for you to say hello to me once, you boozed-up, burned-out Welshman.”

JANUARY 13, 1964: Richard Burton, making a statement without a drink in his hand, says: “We do not any longer expect Miss Taylor’s divorce to come through quickly, and I imagine it will be about six months before we can get married.”

The thwarted bridegroom doesn’t seem frustrated or disappointed as he mouths the postponement announcement; nor, for once, does he seem in need of a quick drink.

January 23, 1964: Liz and Burton, arriving in Los Angeles to “confront” Eddie Fisher about speeding up the divorce, found a mob of fans, reporters and photographers awaiting their plane, and, according to UPI, “fled to a bar near the airport for four quick slugs of vodka before going on to their hotel.” Eventually they got into a limousine and sped away. “With the press in pursuit, Burton and Miss Taylor stopped at the King K’s restaurant-bar for two martinis each, but left when reporters asked t hem questions.” They arrived at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. “They ordered more drinks and dinner.”

Ten quotations, statements, actions fusing into a pattern of self-destruction: exhibitionism (the need to shock others by acting badly or outrageously in public, as if one’s private life were dull, boring or meaningless), masochism (the need to experience suffering, pain and humiliation because of the guilt one feels in a situation or relationship), and alcoholism (the need to escape from unbearable reality into a liquor-induced phantasy world, or, to quote one of Richard Burton’s favorite poets, A. E. Houseman, “Ale, man, ale’s the stuff to drink / For fellows whom it hurts to think:/ Look into the pewter pot / To see the world as the world’s not”).

Was it always like this with Burton? with Liz? with Liz and Burton? And, if not, what events—in the real world, in the inner world of emotions—brought them to their present State? What did it?

How it all started

In the beginning, back in mid-January, 1962, it was all casual and in fun. Burton was bored with just lying around in the sun for four months while Liz and Rex Harrison emoted in front of the cameras; and Liz was . . . was restless.

Then one day Burton, strictly a hard liquor man, was wooing Liz with mixed drinks and . . .

Suppose we let a member of the “Cleopatra” crew tell us what happened, just as he told writer Joe Hyams about it: “First indication I had of it was when I saw Dickie waiting by Liz’ dressing room with martinis in his hands, waiting for Liz to finish work.” At about 5:00 p.m. that day, Eddie Fisher showed up in the green Rolls-Royce as usual (a present to him from Liz) to pick up his wife and take her home. But Liz was in no hurry to leave: a cocktail party was going on in her dressing-room building and some of the cast and crew members—and she and Burton— were enjoying themselves too much to want to break it up just because Cleopatra’s husband was there to fetch her.

So it began, and so it continued for Liz and Burton. Cocktails each night after work. Champagne at lunch. The sounds of Welsh drinking songs, his voice and her voice mingling, from his or her dressing room.

But suddenly their drinking and their romancing burst out into the open, spilled over into public bars and restaurants and were blazoned in banner headlines throughout the world. It was as if Liz, fretting and feeling confined after months of hospitalization, convalescence and hard work, just wanted to cut loose. It was as if Burton, fed up with inactivity (and, so some said, welcoming all the publicity) just didn’t give a damn.

A typical night would find them roaming the Via Veneto, starting off with cocktails first at a restaurant before dinner, washing down their food with vintage Burgundy, visiting half a dozen night clubs, driving to the Pipistrello (the Bat) where they danced cheek to cheek, held hands and toasted each other with champagne, dropping in at Bricktop’s fer more champagne, and ending up for a nightcap at The Little Club at three in the morning.

Then, as it became evident to Burton that he would have to choose between Liz and Sybil, and as it became clear to Liz that his decision was the most important thing in the world to her, their drinking took on a more desperate character.

Jack Brodsky, a PR man on the picture, reported to his sidekick, Nathan Weiss, in a letter dated Rome, April 9: “The pressure is mounting and all of us feel it. Even Burton, usually the great guy, is now nervous, irritable, drinking. Shamroy [cinematographer on the film] predicts Burton will end up like John Barrymore.”

On the night of the day that the Vatican City weekly, Osservatore Della Domenica, castigated Liz for leading a life of “erotic vagrancy,” she went with Burton to a dimly-lighted night club off Rome’s gay Via Veneto, where she sipped champagne cocktails and danced the Twist with him.

Less than a week later, when correspondent Serge Fliegers caught up with Liz and Burton at a Via Veneto spot and informed the actress that there was a report going the rounds in the United States that Eddie Fisher was planning to marry Natalie Wood, she switched from champagne and, in the newsman’s own words, “sought refuge in whiskey and a rare vintage burgundy.” Sometime along the way, “she gulped down a stiff highball, lit her umteenth cigarette and with a short laugh said, ‘If it’s true I wish them all the happiness in the world.’ ”

Exactly ten days following this, the wormwood turned—from whisky and vintage burgundy to vodka. Richard had gone off to the airport to meet another girl (blond, blue-eyed, chubby Kate Burton, his four-year-old daughter) and his wife, Sybil. Liz, deserted and desolate in her $3,000-a-month villa and under heavy sedation “for my nerves,” received a friend with a glass of vodka in her hand and cried (obviously referring to her fight to hold Burton) : “I am finished! But I won’t give up as long as my strength will last.”

But Burton bounded back, and the two lovers went off for a long Easter weekend at a romantic hideaway in Porto Santo Stefano, a rendezvous that began with a breakfast of scrambled eggs, fried lean bacon and ice cold beer, progressed to an impromptu picnic on the beach topped off with a thermos of chilled Frascati wine, and climaxed by a last-day luncheon of fragrant fried shrimp and Liz’ favorite French champagne—Dom Perignon. But the time for departure came and went. Many hours and two bottles of Dom Perignon later, the lovers fought, Liz collapsed and she was rushed to Rome’s Salvator Mundi Hospital.

After this, to observers of Liz and Burton, it was unclear whether the lovers were drinking to live or living to drink.

Months later, when this “Cleopatra” period telescoped into a fuzzy memory, Burton boasted to an interviewer, “I am one of the few people I know who drinks only when he works”—that is, after he comes off stage or off set, he must drink to combat the letdown, the flat dullness of non-theatrical reality. (In a still later interview, Burton amended this and admitted that he also drank during interviews. which frighten him.)

But either he preferred to forget the times he did drink while he actually was working, or else he was being maligned by writer Jimmy Breslin who, in covering the New York opening of “Cleopatra,” observed: “He’s a Welsh guy and these people have this big holiday, March 1—St. David’s Day. Well, the fellow went out ali night celebrating and he showed up in the morning with a big beer in his hand and then passed out. They couldn’t shoot the picture that day. He wakes up later, and what does he do? He offers to pay for the delay out of his own pocket.”

By the time Liz and Burton put Italy behind them, the pattern of their drinking had become set and fixed: Burton was now a heavy, habitual drinker; Liz—partly because of the uncertain, shifting nature of her relationship with Burton, partly because in order to stay with him she had to drink along with Dick—was no longer an occasional drinker.

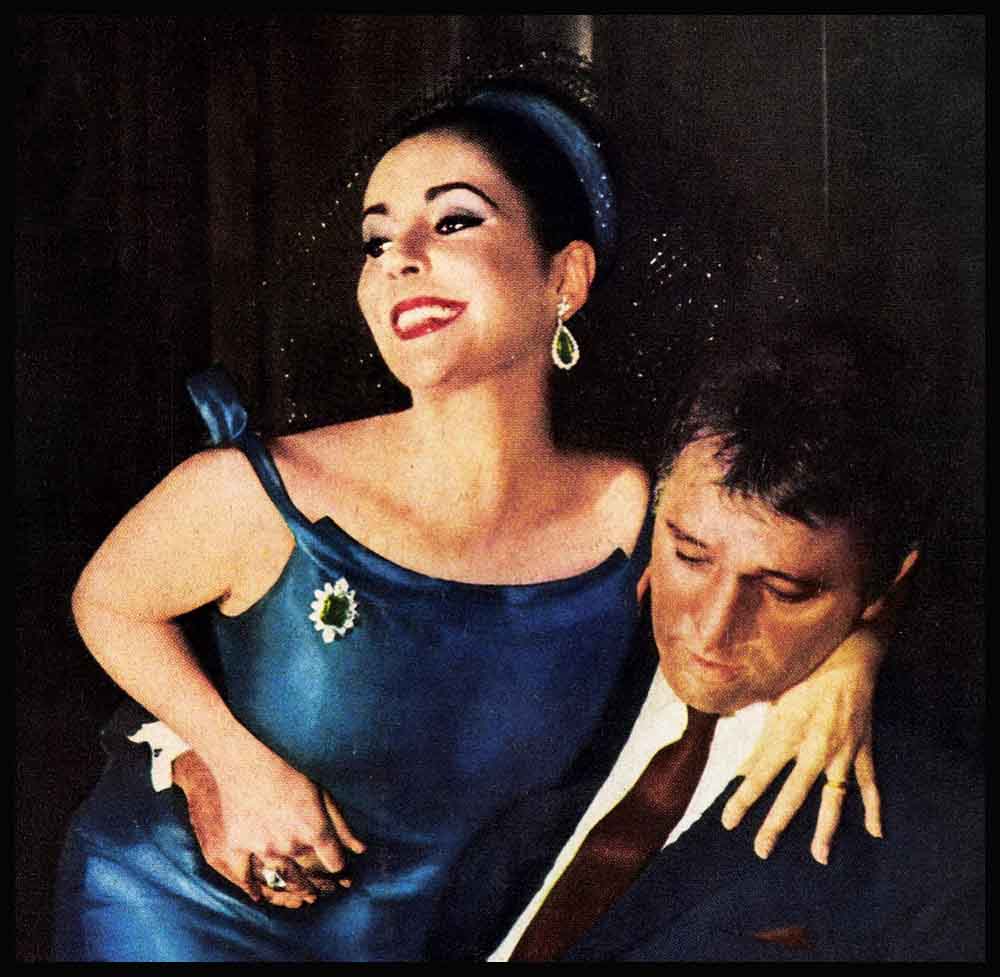

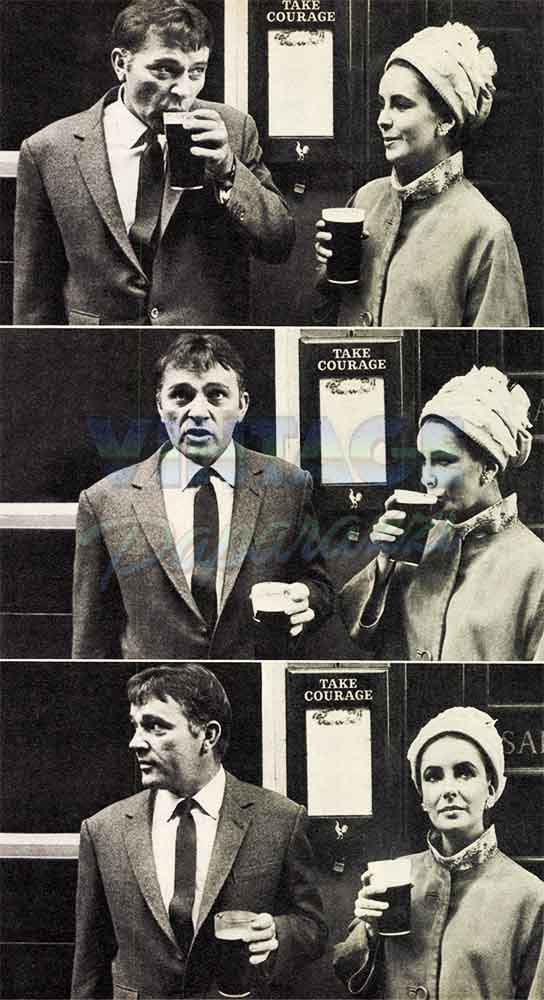

After relative quiet interludes in Switzerland and Paris, the lovers’ drinking and romancing flowed back into the news when they arrived in London. From their head-quarters in the bar and lounge of the Dorchester Hotel, Dick and Liz sallied forth in search of excitement. And excitement, for them, usually was spiked by liquid refreshment.

They whirled from pub to Rugby match to club house bar to prize fight to pub. And it was at a pub called The Load of Hay following the London vs. Wales Rugby match, that Burton’s heavy drinking brought him trouble in the form of the fists of some lads who, it turned out, were also rooters for Sybil. (Later, referring back to this incident when “six blokes . . . rearranged my face a little bit,” Burton confessed: “Sometimes I have a slight apprehension of death. But any physical fear was beaten out of me as a kid. Except I suppose I share every man’s fear of being beaten up in a pub brawl.”)

But except for this one unpleasant experience, Dick and Liz whirled on merrily in an aura of beer and booze.

There were occasional warnings, of course, like writer Jerry Tallmer’s admonition: “There is one symptom: Burton is drinking more than ever before in his life.” But in the main, life was a ball. In an interview at the most conspicuous table in the cocktail lounge of the Dorchester Hotel, Liz, beautiful in lavender sweater and slacks, asserted that they both prefer pub-crawling to theater going for “soaking up our culture.” Burton gave laughing assent, especially to her use of the word “soaking.” But it was another member of Burton’s family, Richard’s brother Graham, who handed Liz the verbal seal of approval: “She can be a jolly good fellow in a pub, drinking her pint with the best. Her language can be as salty as a sailor’s, but she is essentially a very feminine person.”

But something new was now added. Namely, Richard Burton began to mix large doses of verbal venom (directed against Liz) with his drinks. He was capable of saying (as quoted by brother Graham) : “She has the shape of a Welsh village girl. Her legs are really quite stumpy. Her chest isn’t anything extraordinary.”

These attacks against her physical appearance fused and confused with Burton’s alternating, “Yes, I’ll marry her”. . . “No, I won’t marry her” statements. Liz, trying to laugh it ali off, told reporters, “He suffers from onomatoveite—he gets drunk on words”—but in truth, his verbal contortions confounded her confusion.

Despite all his statements to the contrary, they did plan to attend the London premiere of “Cleopatra.” At the last minute they bowed out because he was too much under the weather to navigate.

After the last scene was shot for Liz’ TV spectacular, she threw a party for the cast and crew at The Anchor, an ancient tavern. Burton packed Liz’ kids into a Rolls-Royce and shepherded them to the celebration. He downed flagons of beer, switched to champagne and got roaring drunk. Hours later, children and Liz in tow, he staggered back to the Dorchester.

In June, 1963, when, in keeping with his characteristic pattern of “making decisions and revisions which a moment will reverse,” he indicates for the umteenth time that he will marry Liz and suggests to her that they seal the bargain with scotch. She says she prefers champagne, and gallantly he agrees.

And then the time came for the happy bridegroom-to-be to take his blushing bride-to-be home to meet his family. Home is the seaside town of Aberavon—not far from Port Talbot, South Wales; family is his sister Cecelia (who took care of Richard since he was two, when their mother died) and her husband, retired miner Elfed James. Sometimes, in the warmth of his sister’s home, Liz really felt engaged to Richard; at other times, especially late at night when he was boozing it up with his old cronies in a local pub and his sharp cutting wit was turned mercilessly against her, she felt a stranger and afraid.

Yet, in addition to alternately glowing and cringing on the prongs of Richard’s love-hate ambivalence, Liz managed to formulate a kind of Booze-Who of Richard Burton’s past from his pub prattlings.

A picture of Richard’s father.

A picture of Richard’s father as a rough, tough, hard-drinking, dominating, sometimes brutal man who “considered that anyone who went to chapel and didn’t drink alcohol was somebody not to be tolerated” . . . A picture of a man who never used a short word where he could use a long one instead . . . A picture of a man who insisted he never drank a lot, but rather was a person of “vast drinking habits” . . . A picture of the father of thirteen children (Richard, the twelfth, was born when his father was fifty) : “He never knew which son I was. We called him Daddy Ni, which means ‘our father.’ He sometimes frightened me. No one quite knew what he was going to do next, which can be quite frightening to a child, you know.” … A picture of a man who died in 1958 without ever seeing his son on the stage or in a film. Once, after stopping at seventeen pubs on the way, he managed to stagger into a Port Talbot movie house where “My Cousin Rachel” was playing. But when he squinted up at the screen and saw his son, bigger than life, pouring himself a drink (as called for in the script), Daddy Ni rose to his feet, muttered “That’s it,” and went out in search of his eighteenth pub.

A glimpse of Richard at Oxford.

A glimpse of Richard’s being forced to drink nearly two pints of beer in thirty seconds or pay for it (as punishment for an infraction of dining-hall rules); but for him this was pleasure not penalty, and he learned to down a sconce of beer, without swallowing, in ten seconds: “So far as I know,” he bragged, “no one has ever wacked that feat.”

A view of Richard in the R.A.F. (“I was the worst that ever flew.”)

A view of the day he was mustered out, which just happened to be the date of his twenty-first birthday, November 10, 1946, when he got roaring drunk with a fellow airman and decided to break a few window panes in the barracks. Using a sharp jab of his fist which would shatter the glass without cutting his hand—and which gave him a pleasant sensation—he and his pal systematically broke one hundred fifty- six windows.

A peek at Richard at Stratford-on-Avon, England.

A peek at what occurred when he’d made it as a Shakespearean actor and, to celebrate, bought his first big car, a Lea Francis. One night, after hours of drinking at a party with his older brother Ivor, Richard staggered to the Street. Then, as Richard recalled it, the dialogue went something like this: Ivor: “You’re too damn drunk to drive”; Richard: “It’s my bloody car and I’m driving it”; Ivor: talking with his hands, pushes Richard against a wall; Richard: “Okay, you drive.”

A memory of Richard—her own memory of a meeting with him ten years be for e, now triggered by his pub talk.

A memory of a Sunday when she was twenty-one. The phone rang in her big house in the Hollywood Hills. It was Richard Burton, the actor in “The Robe,” and his wife Sybil. They’d just picked up their friend, actor Emlyn Williams, at the airport, and they wondered if they might drop up for a drink, Emlyn and her husband, Michael Wilding, both being British and all.

So they came, and, taking time out from diapering her baby on the rug, she’d served them drinks. And that was that.

A sense of what Richard had been like in New York during his ten-month stint in “Camelot”—the darling of the cast.

A sense of how Richard’s dressing room had looked, the most important object of furniture of which was a large refrigerator filled with ice cubes. The place was known by the celebrities and pretty girls who met there daily and nightly as “Burton’s Bar.” “Why not?” Richard explained. “It was the cheapest bar in town.” And popular.

Richard’s beer-inspired recollections of his own past obviously set off a train of memories of Liz’s own, memories in which drinking played a Central part.

Memories of going to Leone’s restaurant in New York when she was a teenager and trying to coax the Army brass there into transferring Glenn Davis, to whom she was engaged, back home from Korea. Right afterwards, she said to columnist Frank Farrell: “That’s that. Now how about a gin and tonic, some of Mama Leone’s goodies and a bottle of red wine” . . . Of being introduced to English beer by Robert Taylor (with whom she made her first British film, “The Conspirators”) at The King’s Arms tavern, the same tavern where she now sometimes drank with Richard. . . . Of downing bottle after bottle of Pimm’s #1 while she was with Mike Todd and pregnant with Liza. . . . Of drinking beer (champagne was forbidden to her) during her convalescence after near-death from pneumonia at The London Clinic. . . . Of sipping five or six glasses of vin rose at lunch at the villa she shared with Eddie Fisher in Rome during the initial stages of filming “Cleopatra”; of paying liquor bills that averaged $450 a week (one week it rose to $700); of taking a case of vodka to the studio daily and. just before the car left home, of having the butler bring her one last glass of wine to drink; of insisting that there be four glasses next to her plate each night—one for white wine, one for red wine, one for champagne, and one for water; of throwing a champagne party for eight (Richard Burton was there) at which vodka tonics were consumed before dinner, champagne was drunk during dinner, and Ivan the Terribles (a mixture of vodka, grappa and ouzo) were downed after dinner. . . . Of attending a New Year’s party with Eddie at a Rome night club (Richard was their host) at which a group of U.S. Marines helped them celebrate with champagne. . . . Of drinking champagne and whisky at the celebration of her thirtieth birthday (Burton was not there), the last party at which she and Eddie were together.

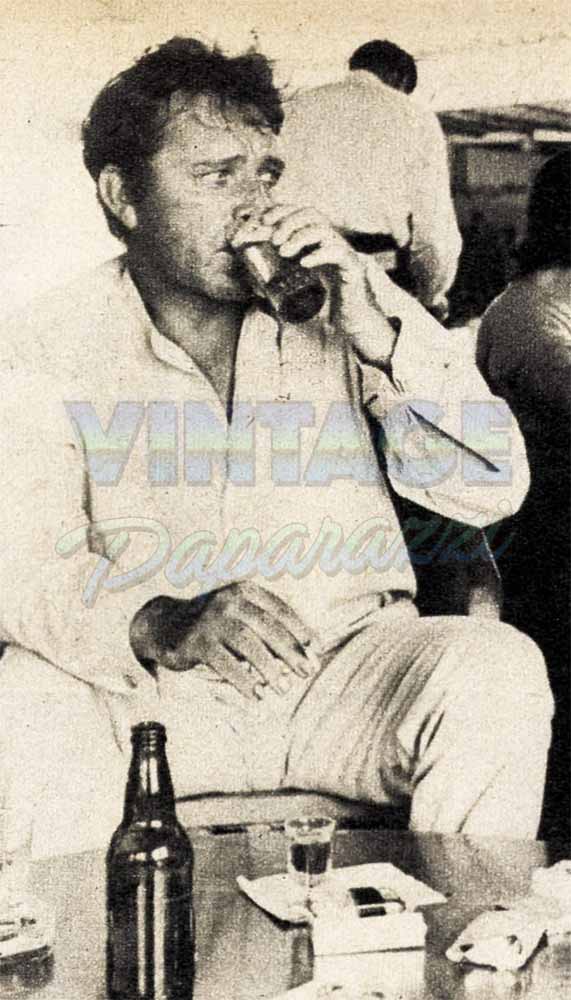

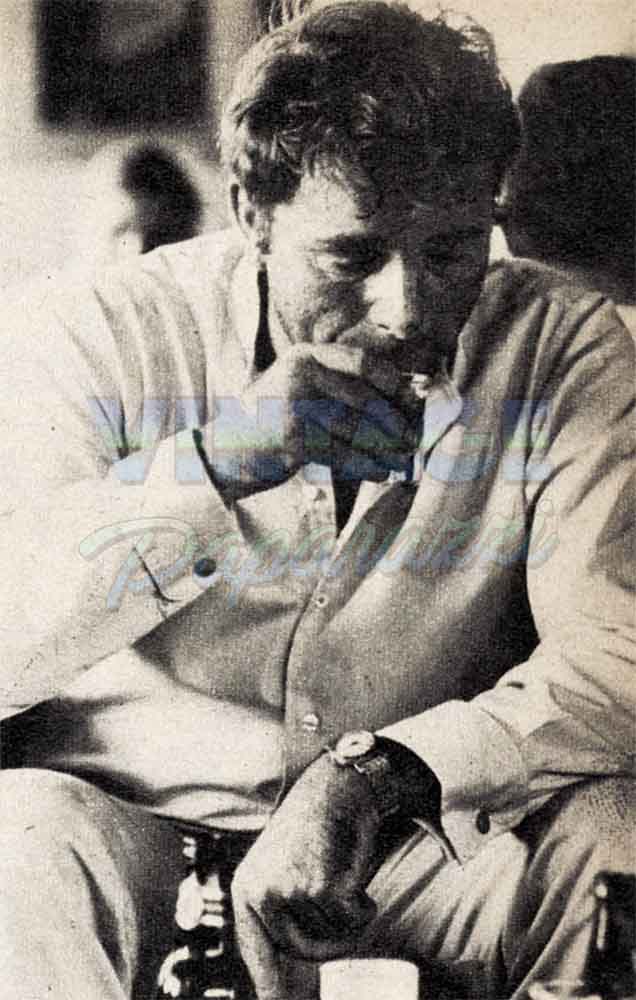

When Liz and Richard arrived in Mexico, the character of his drinking changed. He discovered “Mexican boilermakers”: straight shots of tequilla with beer chasers. (“The script says I’m supposed to be drunk and feverish,” he cracked, “and I’m a Method actor.”) He insisted that tequilla had medicinal value—one night he drank tequilla on the beach, while the others, including Liz, were drinking something else; the next day the others were covered with insect bites, while his skin was untouched. He also tried raicilla, a fiery cactus brandy, the 180-proof distillate of the maguey plant, and gave it his blessing by declaring, “If you drink it straight, you can feel it going into each individual intestine.”

It wasn’t just that he was drinking different potions, it was the way he was drinking them that was significant. As D-Day (Liz’ divorce day) approached, he started earlier, came home later, and gulped each glass down more quickly. He drank with Ava Gardner, with visiting newsmen, with writers, with other members of the cast, with anyone he could corral into bending elbows with him. When Liz wanted to be near him, she had to go to a tavern to be by his side.

Once in a while he was outgoing and mellow.

But more often he was sullen, morose, introspective. Until this time he had always somehow managed to keep his social drinking separated from his acting chores (or, to be accurate, he had been able to effect this separation most of the time). But one day he arrived on the set pale and queasy and shaking. He tried to laugh the whole thing off by varying a line he’d delivered before: “I’m a Method actor; I prepared for this scene by drinking boilermakers for five hours.” Yet his crack fell flat.

Most observers in Puerto Vallarta established a correlation in their own minds between the increasing frequency and severity of Burton’s drinking and Liz’ impending divorce and Richard and Liz’ impending marriage. One newspaper columnist, Jack Kofoed of the Miami Herald, reacting to the joint Burton-Taylor announcement of their forthcoming marriage, which they made at the Playa D’Oro, commented: “A bar was about the most appropriate place the couple could have chosen.”

What was happening to Burton, the reluctant bridegroom, seemed obvious; it was more difficult to pin down what ali this was doing to Liz. Surely she must have been joking when, watching Burton from across a bar, she said: “I’ve been sitting here for half an hour, just waiting for you to say hello to me once, you boozed-up, burned-out Welshman.”

Or was she? Would anybody know?

The future — a question

The strength of Richard Burton—and the attraction of him for Liz, as she has said many times herself—is his forcefulness, his ability to dominate her. But there can be no forcefulness, no domination, when there is no contact—when the man constantly drowns himself in drink and persists in looking into the whiskey glass or “the pewter pot to see the world as the world’s not.”

When Richard Burton announced that there would be a postponement of their marriage plans, that they would not marry in Mexico, there was no liquor glass in his hand. It was as if he’d been given a reprieve, a delay, and for once didn’t need outside stimulants to sustain him.

But as each obstacle to their marriage crumbles and the inevitable wedding day approaches, it is most likely that his exhibitionistic, masochistic. alcoholic streak will assert itself again. Then the question “How Long Can Burton Hold Liz and His Liquor, Too?” will once more be placed squarely in Liz’ lap—a question and a problem that can sour her fifth marriage before it hardly begins.

—By JAE LYLE

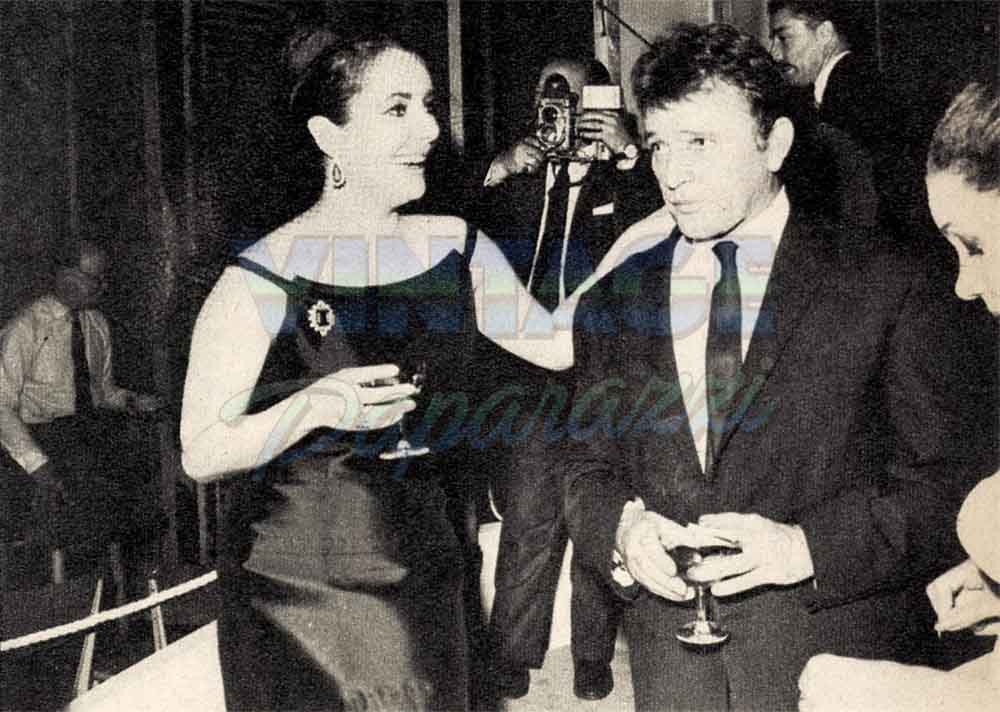

Liz and Burton appear together in 20th’s “Cleopatra” and M-G-M’s “The V.I.P.s”. Burton’s latest films are “Becket” for Para, and “The Night of the Iguana” for M-G-M.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1964