How It Feels To Act In The Nude—Carroll Baker

You had to be very close to Carroll Baker to see that she was trembling. But of course, no one was very close to her. The British wardrobe mistress had slipped Carroll’s bathrobe from her shoulders, and watched as Carroll hastily slid beneath the sheet on the bed. Then she had turned away and carried the bathrobe silently back to the star’s deserted dressing room.

The prop men, the grips, the extras, even the assistant directors and lighting technicians of. the big London studio had disappeared from the sound stage. “The set has to be cleared,” Carroll had insisted, and from the door of her dressing room she had watched them depart. Were they snickering a little, walking away? Has someone joked about sneaking back to get one fast look at her, whether she liked it or not? Maybe. It didn’t matter. They were all gone, the door closed behind them, the “closed set” sign had been posed. Every non-essential man had been banned.

But the essential ones, of course, remained: the director, the chief lighting man, the cameraman. They were all far away from her right now, being very busy about their work. Very professional. A few minutes ago—or was it a few hours?—they had all discussed the scene together, very professionally. “Our problem, Carroll,” the director had laughed, “isn’t how to show your body, but how to avoid showing it too much.” “It’s a matter of mood. Miss Baker,” the lighting man had told her. “The scene is going to be great,” they had agreed. “The irony of this doomed girl getting out of bed with nothing on, putting on an ermine trenchcoat, and then going out and getting killed by her lover—it’s absolutely marvelous!”

“. . . handle it with taste!”

And she had been just as professional, just as composed as they. “Yes,” she had said, “it is very well motivated. I know I can trust you to handle it with taste!”

But that was before. Now she was not so sure. Now she did not feel quite so professional. Now she was not thinking of motivation, of the part, of the fact that she was an actress.

Suddenly she was only a woman lying naked in a room with three men. The millions who would eventually watch her on the screen didn’t matter, but these three men did.

The cigarettes she was to smoke in bed at the beginning of the scene were ready. Carefully, Carroll lit one. The big thing was to concentrate—on her part, on the scene, on anything but the fact that the three men were looking at her. On anything but the brutal lights, standing ready to illuminate every line of her body.

She couldn’t help the way she felt about the lights. Because after the cameras started to roll, after she had smoked the cigarette, she was going to have to push the sheet aside and get out of bed. Bathed in those lights, she was going to have to walk completely nude across the set to where the trenchcoat was hanging.

Funny. On the screen the scene would appear dimly lit; dusky, shadowy. People might walk out saying, “Listen, for all you could tell, maybe she was wearing flesh-colored tights!”

But Carroll knew. And the three men watching her knew, too.

And after all—they were men. Professionals, but still men. Carroll pulled p the sheet around her. What were they thinking now? What would they be thinking in five minutes, when she stretched her legs over the side of the bed and stood up?

Her cigarette burned down. Carroll thought of her husband. He wasn’t here, of course. She didn’t like him to watch her work; it made her nervous. Today, it would have made things impossible. But Jack hadn’t come. Maybe he hadn’t even realized this was the day of the nude scene—she hadn’t discussed it with him, really. In fact, it was almost as if there had been a silent agreement that no one would talk about it beforehand. Possibly they were all trying to pretend it wasn’t there.

But it was there—it was here, and now.

“Ready, Miss Baker!”

Carroll sighed. “Station 6 Sahara” would be another of the pictures she wouldn’t be taking her two children to see. They had seen her in only one—“How The West Was Won.” The rest—well, they weren’t pictures for children. Children, Carroll thought, fighting hard now for control, children should go to Walt Disney movies. She, as an actress, preferred to do adult scripts. After all, she couldn’t deny she was a modern woman—wasn’t she?

Embarrassed and unhappy!

But even so, as the cameras rolled, Carroll, going through her scene, blushed red across her cheeks and brow and knew in her heart that she was embarrassed, frightened and very, very unhappy.

Carroll’s husband, director Jack Garfein, saw the rushes the next day. Carroll waited anxiously to hear what he thought. Had she done the right thing? Would he be shocked? But Jack said only, “From what I know of the story, the scene is well motivated. I don’t know whether you should have done it or not—but that’s up to you.”

Her mother was not so diplomatic. “Carroll,” her mother said on the long-distance telephone, “you’re such a nice girl in your private life—why do you do things like this on the screen?”

It was the question everyone was asking—not only of Carroll but of Kim Novak, Shirley MacLaine and Arlene Dahl, Jayne Mansfield, Sarah Miles—and others who had posed nude for the camera. But Carroll Baker was the only one to answer it.

“All our barriers are breaking down; we’re reverting to a pagan society. If the First Lady wears tight Capri pants and a swim suit, what are we poor actresses to do to attract attention?”

Carroll sat in the handsome living room of her New York apartment. Her voice was steady; her hands were still. But her face was flushed as she spoke, just as it had been the day she walked naked across the set in the hot London studio.

“When I first went to Hollywood, about seven years ago, Warners—my studio—only used starlets to do cheesecake. Cheesecake was looked down on! If you appeared in a bathing suit, you weren’t an actress. Eva Marie Saint and Lee Remick, who were starting at about the same time, even Natalie Wood who was making her comeback then—stuck to that policy. If you had on a sports outfit, it was a pair of slacks or shorts—and not very short shorts. Today, the First Lady of the Land is shot in bathing suits which would have been unheardof a few years back—and tight Capri pants. It wasn’t just that Eleanor Roosevelt and Bess Truman and Mamie Eisenhower wouldn’t have looked well in them—there were simply rules for women then. For ladies. You wore a tight girdle so there was no chance of anything really showing. Your decolletage went only so low—no lower. But the modern woman—she’s been freed. She deals constantly with men on fairly equal terms. She earns the living or helps earn it after she gets married. All the barriers around a woman are crumbling. The divorce rate is climbing. Many women are disillusioned with religion as a moral basis for their lives. Others believe that only today is important, how much fun I have today—and to hell with tomorrow. Even women in Society are affected. It used to be that they went to any lengths to keep their names out of the newspapers—it was only girls from the wrong side of the tracks who wanted to be celebrities. Now the whole world is celebrity-mad, and even Society women want to be famous. So they pose in revealing outfits—because in our sex-preoccupied world, that’s what gets attention. That’s how it is, I guess.

A work of art

“At home,” Carroll said flatly, “I’m straitlaced. I’m strict. I believe in maintaining the foundations of the home, in basing my life on a moral and ethical code. I hate the fact that my children—all children—are growing up surrounded by this whole atmosphere of loose morals!”

Then why had she—who so obviously disapproved of such behavior—agreed to act in the nude?

“I’m an actress. I want to play roles that reveal my time—I want to show today’s woman as she is. And if it is necessary to ‘do a nude scene—or a realistic love scene—to show her honestly, then I must do it.

“I would act nude only when it was really essential to the script—as it is in “Station 6 Sahara”—and when it is done in good taste. Sex doesn’t have to be pornographic. “Baby Doll” was a work of art. “Sahara” is a good movie.

“There’s nothing wrong with the human body. Isn’t a woman’s body as important as her other facets? Is she only a face, a soul, a mind? I really don’t think so.

“Anyway, it’s no use making a movie no one goes to see. If we want the European audience, which is accustomed to realism, we have to go along with the form their movies have taken. We have to try not to be childish about it.”

They were good answers. So good that it would have been easy to assume that the young actress who gave them had no doubts at all.

But Carroll Baker has doubts. Despite all the excellent reasons, despite all the well-thought-out rationalizations, she gives one the distinct impression that she is deeply troubled about what she has done and may one day be called on to do again.

“I have to separate what I do in my work from what I am at home,” she said slowly. “My work has no connection with what I believe ethically and morally, and with what I want out of my private life. Yes—I keep them separate. . . .”

Yet, there is a danger in splitting one’s life neatly in two. For the day may come when Carroll’s two small children will see outside a movie theater, a titillating photograph of their mother in the nude or semi-nude, her private and professional lives will come together with a crash.

“You can’t protect children from the world,” Carroll says now. “When my children are old enough, there’s nothing they can’t see, experience. I hope they will he mature and understanding enough.”

But is confidence enough? Carroll has confidence that “Station 6 Sahara” is not a vulgar film—but she had to threaten to sue its producers a few months ago because of a dummied-up publicity photo which featured her head on the body of some other woman in the act of removing her brassiere.

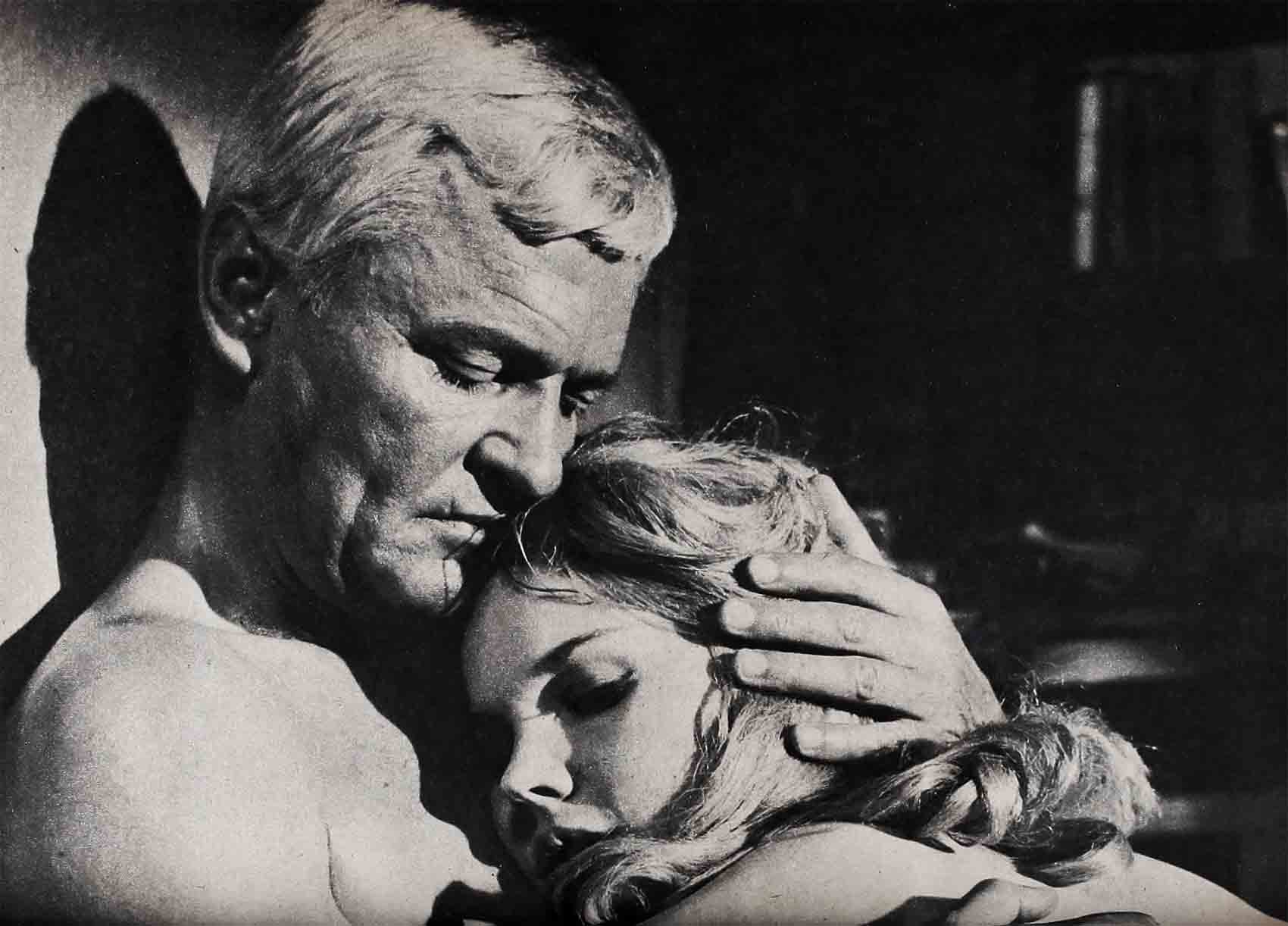

She has confidence that the people who see her in the film will agree that the nude scene is justified by the story—but because of that scene, and the realistic love scene with co-star Peter Van Eyk (shown at the beginning of this story), the film is having censorship problems in the United States and may never be seen here in its entirety!

We live in a sex-obsessed society. Sex is used to sell cigarettes and automobiles and clothing—on billboards, in newspaper ads, on TV. Radios and juke boxes blare erotic rhythms and suggestive lyrics day and night. Books sell on the strength of the number of four-letter words they contain, and movies on the “shock” value of their love scenes.

Is this necessarily bad?

Is the human body, revealed to our eyes, evil—or good? Or is it only the nature of its revelation—in a painting by Renoir or in a ‘girly’ magazine—that determines its morality?

Is it right—or wrong—to show our times and our selves as they are, rather than as some think they ought to be?

Philosophers, psychologists, educators and social workers are hard at work on these problems—and finding clear-cut answers hard to come by.

It is hardly surprising that Carroll Baker doesn’t yet have them all—and is, beneath the surface, confused by those she does have.

But until the answers are known, Carroll and all the dozens of other actresses who, with troubled hearts, are now working in the nude, will have to wonder—worry—wait—and hope for the best.

—SY BARBER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963