How Esther Williams Has Changed?

About a year ago, on Wednesday, July 20, 1955, at shortly after five o’clock of a smoggy Los Angeles afternoon, Esther Williams, 32, formerly employed by the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios as an actress, drove her late-model Cadillac through the MGM gate on her way home.

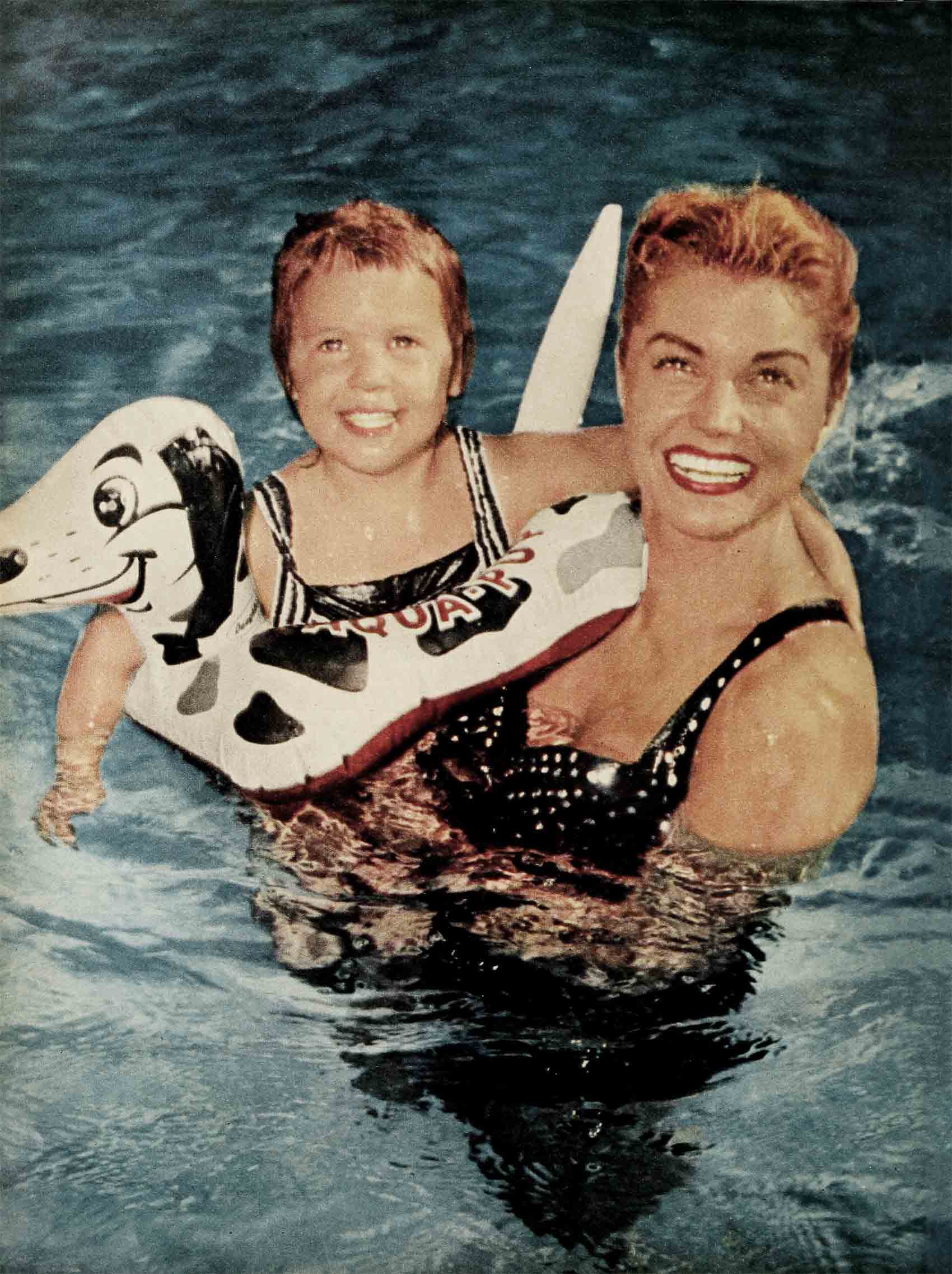

Esther was going home to her husband, Ben Gage, and her children, Benjie, 6½, Kimmie, 5½, and Susie, 1½, with extensive plans for a “new” career.

Now it’s a familiar gambit to write of the “new” Esther Williams or the “new” any other movie star. Yet it is a matter of observed fact that Esther today is quite different from the Esther Williams I first met back in 1949. She lived then in a ridiculously small house tagged “Hodge-Podge Lodge” by her friends. She was one of MGM’s most dependable stars, meaning money-makers. Ben had a local TV show called The Rumpus Room. Benjie was only a matter of months old and Esther was fighting the good fight with the diapers.

Two years later, in 1951, I sat across from Esther in the “keeping room” of her brand new farm house. It was Kimmie’s turn to be only a matter of months old. Ben had given up the TV show to devote his full attention to managing the various business enterprises that Esther kept getting into. And Esther was still the dependable movie star.

“I’m no Ethel Barrymore,” she said to me that night. “I have no illusions about myself as an actress. Wet, I’m good. Dry, I’m nothing. The minute the public gets tired of seeing me dripping wet, I’m going to quit and come home and spend the rest of my life being a wife and mother.”

I knew Esther well enough to know she wasn’t kidding and.that she meant every word of it. I also knew her well enough to know that she was an exceptionally gifted wife and mother and that the “husband and kiddies” routine was no false front.

Yet five years (and one daughter) later, Esther walked away from MGM with plans to keep herself busier than the studio had ever dreamed of keeping her, Why? And what was to happen to the children, the ones with whom she was going to spend so much time when she quit?

“The lethargy of staying at the studio was getting me down. I just couldn’t sit there any more. We stretched one basic script out over a period of fourteen years and twenty-two pictures. Except for the costumes and the locale, they were all the same. All of a sudden I had to prove that it didn’t have to cost over $3,000,000 to make a picture with me and that without forty-eight dancing girls backing me up I was nothing. It kind of made me mad to have people think I couldn’t do anything else but stand there dripping wet and then dive back into the pool again.”

As for the children, Hollywood had long since learned for itself that the three Gage kids come first where Esther Williams is concerned. A top agent called her on the phone one evening several years ago and launched into a business discussion. He had the feeling that he wasn’t getting the message across, a feeling that was confirmed when Esther suddenly broke off with, “I’m sorry, I’ve got to go. Benjie has a loose tooth,” and hung up. A small boy’s loose tooth was more important to her than a great deal of money. It’s part of Esther’s basic charm that she can cope with Hollywood’s hardest-headed businessmen on the phone while standing there with a runny-nosed child under her arm.

Yet the soft, sentimental side of Esther Williams is reflected in one of her last acts while at MGM. “It’s funny,” Esther says, “but a few months before I had even thought of trying to get my release from the studio I suddenly had a terrible urge to re-decorate my dressing room. So I did—all white and movie-starrish. Yet I knew even while I was doing it that I’d never use it. I hope Debbie Reynolds gets it. She’s a nice kid. All I was doing was what every woman does when she realizes she’s going to leave. She housecleans. She wants to leave everything neat and tidy behind her.”

Fame, Esther realized suddenly in the summer of 1955 meant little or nothing any more. What counted now was that she could work for fun and, more important, that she and Ben could work together.

“I had never realized it before,” she explains, “but all the time I had been in pictures I had never had to lean on Ben. I do now. We’re a team and he’s my husband and I lean on him but good. Fortunately, he’s big enough. And in more ways than one.”

What were the plans with which the confident Esther was going to launch her “new” career? And how did she intend to reconcile these plans with the bringing up of her three children?

“Easy,” says Esther, who swims twenty-five laps a day, every day, and to whom the word impossible is as a light cold to a pneumonia specialist. “I’m going to spend just as much time with the children now as I ever did, if not more. And when I’m with my children, I’m with them.”

Esther isn’t just phrase-making. Several years ago, when Benjie and Kimmie were younger and a good deal lighter than they are now, the four Gages were having dinner at a small desert resort where they were spending a weekend. Benjie and Kimmie, being children, started to act up at the table. When the usual parental warning signals failed to register, Esther simply picked them up, one under each arm, and marched out of the dining room. She kept on marching, right up to their room, sat them down, ordered their dinners sent up and stood a pleasant but firm guard over them until they had finished.

The plans? The big one didn’t really begin to materialize until the week Esther made her first television appearance as a guest star on Milton Berle’s first show of the 1955-56 season. She already had enough things going for her to keep her financially solvent for the rest of her life. What she wanted now was some fun, something she could throw herself into with the same kind of fresh enthusiasm that took her so quickly to the top of the movie heap. She found it on the Berle show.

“NBC had built a swimming tank for the show,” she explains. “I had seen swimming tanks before. Practically lived in them, in fact. But this one, for some reason, made something click in my mind.”

The click resulted in the Esther Williams Aqua-Spectacle of 1956, a title which suggests—and correctly—that there will be an Esther Williams Aqua-Spectacle of 1957, and no doubt 1958 and 1959. Fully financed by NBC (in return for four Esther Williams ty shows over a period of two years plus-a share in the Aqua-Spectacle profits) it opened in London July 30, on NBC-TV September 29 and then took off on a cross-country tour that will last into March or April of next year.

“Oh, great,” was her friends’ reaction to this brain child. “And what are you going to do about the kids?”

“Why,” said Esther, “we’ll take them with us. What else?”

Last April, with all the tentative plans for the Aqua-Spectacle beginning to fall into place, Ben flew to London to iron out all the practical details for the July 30 opening. Why London? “Because,” said Esther, whose business head is the despairing envy of every young starlet in Hollywood, “it costs a lot less to put such a show together in England than it does here. Furthermore, it will be thoroughly broken in before we bring it back for the TV show—and not a soul in the United States will have seen it.”

Details. Ben rented an eight-bedroom house in St. John’s Woods, the Bel Air of London. Esther arranged for a young Swiss girl to serve as a tutor for Benjie and Kimmie. Jane Boyd, the children’s nurse for the past four and a half years, Was promoted to Esther’s maid. (“That was Ben’s idea,” Esther grumbles. “I don’t need a maid.”)

Monday, June 18—boom! Everybody back to work. Benjie and Kimmie pored excitedly over a new geography book, soaking up everything their young minds could absorb about England.

“How do you feel about going abroad?” Benjie was asked.

“We’re not going abroad,” he announced firmly. “We’re going to London.” It was a difference every Englishman appreciated hugely.

Right in the middle of everything, just two weeks before they were scheduled to leave, death struck.

Al Scarcella, Esther’s and Ben’s longtime business associate and close family friend, was burned to death in a tragic accident. Esther turned to her children. “Uncle Al has gone to heaven,” she told them gently. “It’s a long trip and he’ll be gone a long, long while. So we must pray for him. You see, Uncle Al has died. So we will pray for him, and that’s the way you will talk to him.”

Benjie thought for a moment. “But you’ll have to tell us how to talk to Uncle Al,” he said finally.

Esther drew deep on her thirty-two years of living and explained it to him.

“Gee,” said Benjie, “you said it just right, Mom. I couldn’t do better than that. G’night.” And he went comfortably off to sleep.

A few days later, little Susie looked up trustingly at a visitor. “Uncle Al died,” she said, solemnly but matter-of-factly.

“I know, dear,” said the visitor.

“I love Uncle Al,” Susie went on.

“Of course you do.”

“I like you, too.”

Children can be so wise.

Life goes on, and Esther and Ben and their children go with it. There is nothing like work. Of that, they had plenty. The children went off to London first, by plane, Jane Boyd sheltering them like a mother duck. “Mommie being interviewed and photographed on arrival,” Esther explains, “is sometimes a little wearing for the kids. Too, they can get all settled without all the business people round. They were met by a parade, and they were paraded all the way to Wembley. They love parades!”

London, Esther predicted on a warm, bright day in June, was going to be a ball. “The kids are going to summer school without even knowing it,” she said happily. “And once the opening is out of the way and the show has settled down, I’ll be with them more than I’ve ever been. We’re going to do the whole tourist bit together—Tower of London, Buckingham Palace, the changing of the guard, the London Zoo—everything.”

The tour will cover from twenty to twenty-five cities depending on how the schedule works out, with a maximum of six days in each city. And it also calls for two identical 180,000-gallon portable swimming tanks. “We work in one and send the other on ahead to the next city to be set up,” Esther explains. “We’ll play in arenas because the tanks, when they’re filled with water, are just too heavy for anything but the solid ground. If we went into a building with a basement underneath the door, we’d wind up in the basement. That’s why we can’t play New York City. Not even Madison Square Garden could hold that tank up.”

Esther gets time off for a Christmas vacation (“That’s probably when we’ll take the kids home for good.”), but the vacation ends abruptly in late December, when the show is scheduled to open in Chicago.

Chicago or no Chicago, it will be a typical Gage Christmas. The big farm house will be overflowing with relatives and toys and Esther may even have time to sit down for a minute and look back. Which is not something she often does. “The past is the past,” she likes to say. “It’s the momentum and enthusiasm of new ventures that counts.”

THE END

—BY LEE CORDNER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956