Hey There, Haymes!

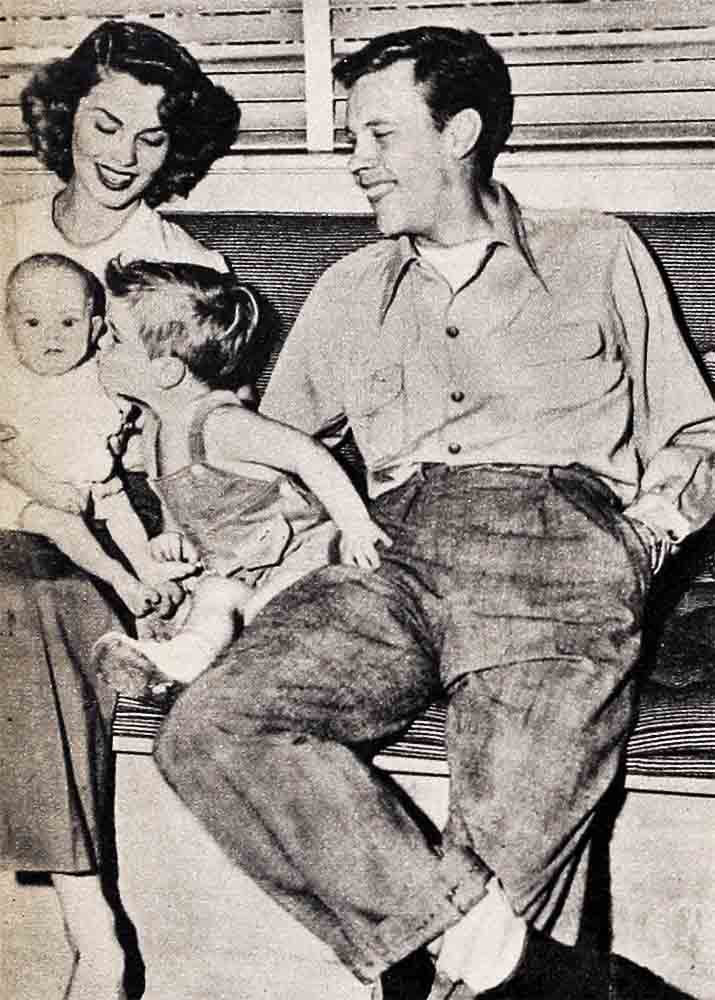

What is a guy going to do when he is $9,000 in debt? When he is behind in the rent and can’t pay the grocery bill? When his beautiful wife has just announced that he’s about to be the father of a second child?

To Dick Haymes, who found himself in that spot just a little over a year ago, there was only one answer.

He quit his job.

Quickly—before Mr. Anthony and the Retail Merchants Credit Association have apoplexy—let it be said that the young man was absolutely right. For the Dick Haymes of the hard-luck story is the same Dick Haymes who today is appearing opposite Betty Grable in “Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe,” who has a seven-year contract at Fox studios, who is starring on his own radio show, “Everything For The Boys,” whose record sales are totaled in six figures, who has a house with a swimming pool in the San Fernando Valley, and no debts at all. The grocery man loves him.

AUDIO BOOK

“I had known for a long time that I had to make a break,” Dick says now, “but when Joanne told me we were going to have another baby—that did it!”

Dick had been singing with bands for four years—ever since Harry James told him that he was a rotten song writer.

“I won’t buy your songs,” James told the embryo composer, “but I’ll buy your voice.”

After that, for three years, Dick appeared in theaters and ballrooms all over the country as soloist with such top bands as James, Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. With all of them he made records. With Dorsey he even made a picture—but you didn’t see him. He was effectively disguised in powdered wig and knee breeches in “Du Barry Was A Lady,” and it was just as well.

“That band routine is murder,” Dick says. “In the first place, a guy in a band has absolutely no right to be married.”

When he asked Joanne to marry him, Dick says, it was because he was terribly in love with her and wanted to be with her. But how much time can a man spend with his wife when he is recording with the band in the mornings, broadcasting with the band in the afternoons and appearing with the band until the middle of the night?

“I was married to the band, not Joanne,” he recalls with a shudder. “When Skipper was born, it was worse. I had to choose between sleeping—the measly four or five hours which was all I had been able to squeeze in before—and seeing my son once in a while.

“Well,” Dick sighs, remembering, “they say some people can get along without sleep. All I got was a bad cold that hung on for months and months and an incipient nervous breakdown.”

He kept promising himself that he’d quit—that he’d have a try on his own, in radio or the movies. But that $150 a week he was getting, and the $20 a side for recording jobs, was pretty important. He dragged along from week to week.

“Joanne was wonderful,” he says. “She put up with the murderous hours—remember, when she stayed up to say hello to me when I got home at three in the morning it was a real sacrifice, for she had to be up at six to give Skipper his bottle. She didn’t complain. She didn’t bother me about the bills, which seemed to make up the bulk of our mail. She must have worried, but she didn’t say so. But I think she was a little scared to tell me about the second baby.”

Dick still laughs thinking of that scene. “ ‘Joannie,’ I told her, after she broke the news, ‘you and Skipper are going home to your mother.’

“She almost burst into tears. She had expected the news to be a new worry—but she didn’t think I’d throw her out.

“I had to explain fast.

“ ‘Look, honey,’ I told her, ‘I think it is wonderful about the baby. You know how much I’ve wanted a family. But you and Skipper and the new baby deserve a better break than this. I’ll tell Tommy tomorrow that I’m quitting, and then I’m going to make good on my own. If I don’t,’ I added, and I meant it, ‘ I’ll drive a truck.’ ”

For a while it looked as though Dick were going to have to take out that truck driver’s license.

He lived alone in an ugly little room in a Hollywood hotel, missing Joanne and Skipper terribly. His cold and “band-nerves” refused to be shaken. He spent every other day in bed, really ill. On alternate days, he knocked on casting office doors—but nobody wanted any leading men, particularly, it seemed, if they could sing, as well.

Then came a long distance telephone call from Bill Burton. Burton is a manager among managers, who takes only a few young hopefuls as clients and then looks after them like a mother hen. Dick had met him through Helen O’Connell, one of Burton’s “little family,” and Joanne’s best friend. He had wanted Burton to manage him, but Burton was sorry. Too busy.

Now, he said, he had time to give Dick the kind of service he deserved.

“Get on a plane and come back to New York and we’ll go to work,” he said.

“I can’t,” Dick replied, “because I’m broke. And besides I don’t want to come to New York. I want to get into pictures.”

“Don’t you know,” yelled Burton over the wire, “that the only way you can get into pictures is to leave Hollywood? I’m wiring you $175—get on that plane!”

So Dick packed his two suits—his blue suit and his bathing suit—and went to New York. Joanne and Skipper and Bill Burton met him at the airport.

“Burton’s face fell,” Dick recalls. “I could see that he was looking at the knitted tie I had tied around my pants as a belt.”

“Gee, kid,” he said, “I didn’t know you were that hard up.”

Dick roared. He happens to like knitted ties for belts.

“I told you I was broke,” he said.

“We’ll fix that,” Bill Burton said, and they did. Within a week Dick was booked into theaters in Newark and Hartford and he enjoyed the sound of the clink of money in his pockets once more. It didn’t last long for he bought Joanne a fur coat and Skipper a tricycle.

Then Burton booked him into New York’s swanky La Martinique. And Dick immediately bought Joanne a car and Skipper an electric train.

“Stop buying presents,” Burton pleaded, “until you get some money in the bank.”

Dick explained that Joanne and Skipper hadn’t had any presents in a long time.

“All right,” moaned Burton, “then we’ll just have to get you some more money.”

He decided to try Dick’s luck at recording. The union ban was on at the time and no orchestra was available, so Dick recorded with a choral background. His first record, “You’ll Never Know,” sold 1,600,000 copies. The first four sides he recorded brought Dick, in royalties, $18,000—a hike over the $20 a side he collected during his band-vocalist days.

Radio was the next step. Dick signed to star on a new series, “Here’s To Romance.” After that the Fox contract was easy. Burton was right. Fox ”discovered” Dick in New York, and rushed him to Hollywood to play in “Four Jills And A Jeep.”

And Dick bought Joanne a house with a swimming pool and Skipper and Helen Joanna—who arrived last May—a truck load of toys.

The suddenness of the switch from bankruptcy to the fat of the land didn’t phase easy-going Dick Haymes at all. You see, his whole life has been like that.

He was born in Argentina, into a wealthy household. Spanish was the first language he learned—from his father, an Argentinan of Irish descent. His American mother, Marguerite Wilson, then a musical comedy star, taught him English, and a governess taught him French. Dick and his brother Bob spoke three languages fluently before they started to school.

They went to school in Lausanne, Switzerland, later in Normandie, finally in Paris—for their parents had separated, and the boys traveled about with their globe-trotting mother. From his mother, Dick learned how easily money is made—and spent. And how very little, if you’re eating, it matters.

He remembers once when he was twelve sailing from New York to Paris with his mother aboard the finest liner afloat. During their stay in France, the dollar dropped on international exchange. They came back on a tanker.

In October, 1929, his mother was worth a million dollars—in contracts with New York stores for gowns designed in her Paris salon.

In November, 1929, the Haymes family was penniless.

It was always like that. Dick always wanted to be an actor. But when no one wanted to buy his Services, he found it easy to adapt himself to circumstances. Before he was twenty he had sold the Atlantic Monthly a series of short stories—based on the mysterious life in the sewers of the Paris beggars. That was the end of his career as a writer—he had decided to be a song writer. But if he knew where to lay his hands on those stories, he’d peddle them again. They are particularly timely in the light of recent reports that the French Underground carried on during German occupation by taking to the labyrinthian sewer system under the streets of Paris.

Dick lived for a year on advances for songs he wrote—not one of which ever became a hit. Some of those advances were among the debts he paid off when he canceled that worrisome $9,000 recently.

Dick was rather fond of some of those debts. One was to Harry James, who loaned him the money for his honeymoon.

“Harry was my best man,” Dick explains. “And a nice guy. He didn’t raise an eyebrow when I told him I had spent all my money for a formal afternoon suit for the wedding and didn’t have a cent in my pocket.”

The doctor who officiated at Skipper’s birth also was surprised with payment in full. So was the hospital where the great event took place.

Dick’s greatest kick these days is that now he’s the one who can loan money to his down-and-out friends.

“They’ll be rich tomorrow,” he says.

He thinks it’s that easy.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1945

AUDIO BOOK