I’m Helplessly Watching My Marriage Die—Dick Gardner

EDITOR’S NOTE:

You loved Dick Gardner as Private Cowley in “The Young Lions” and swamped us with fan letters which we forwarded to him. He was most grateful for your interest. Now Dick’s in trouble. He asks you to read his story and then write a letter to him and his wife Joan. The address is:

c/o Twentieth Century-Fox 10201 West Pico Boulevard Los Angeles 64, California.

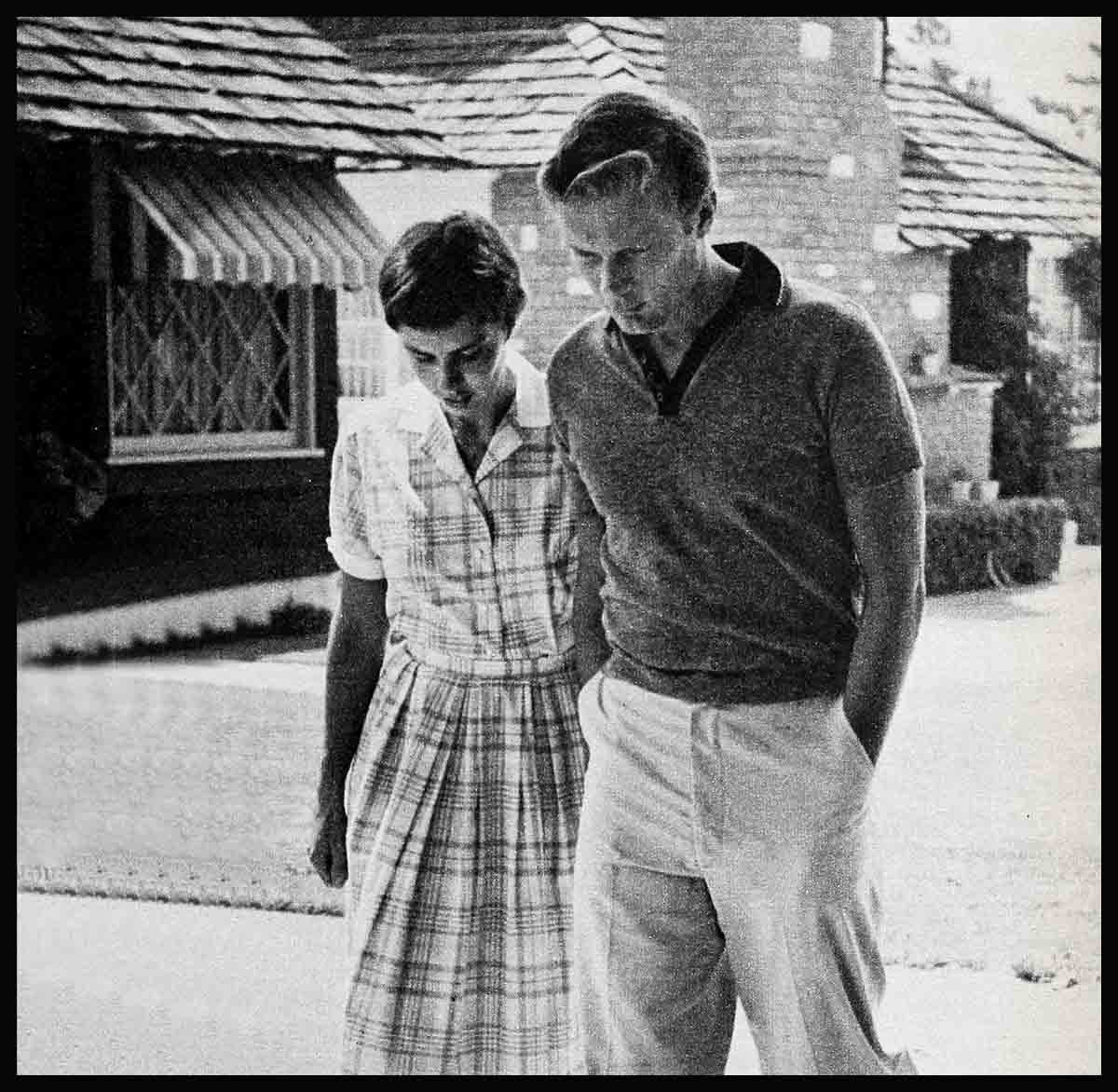

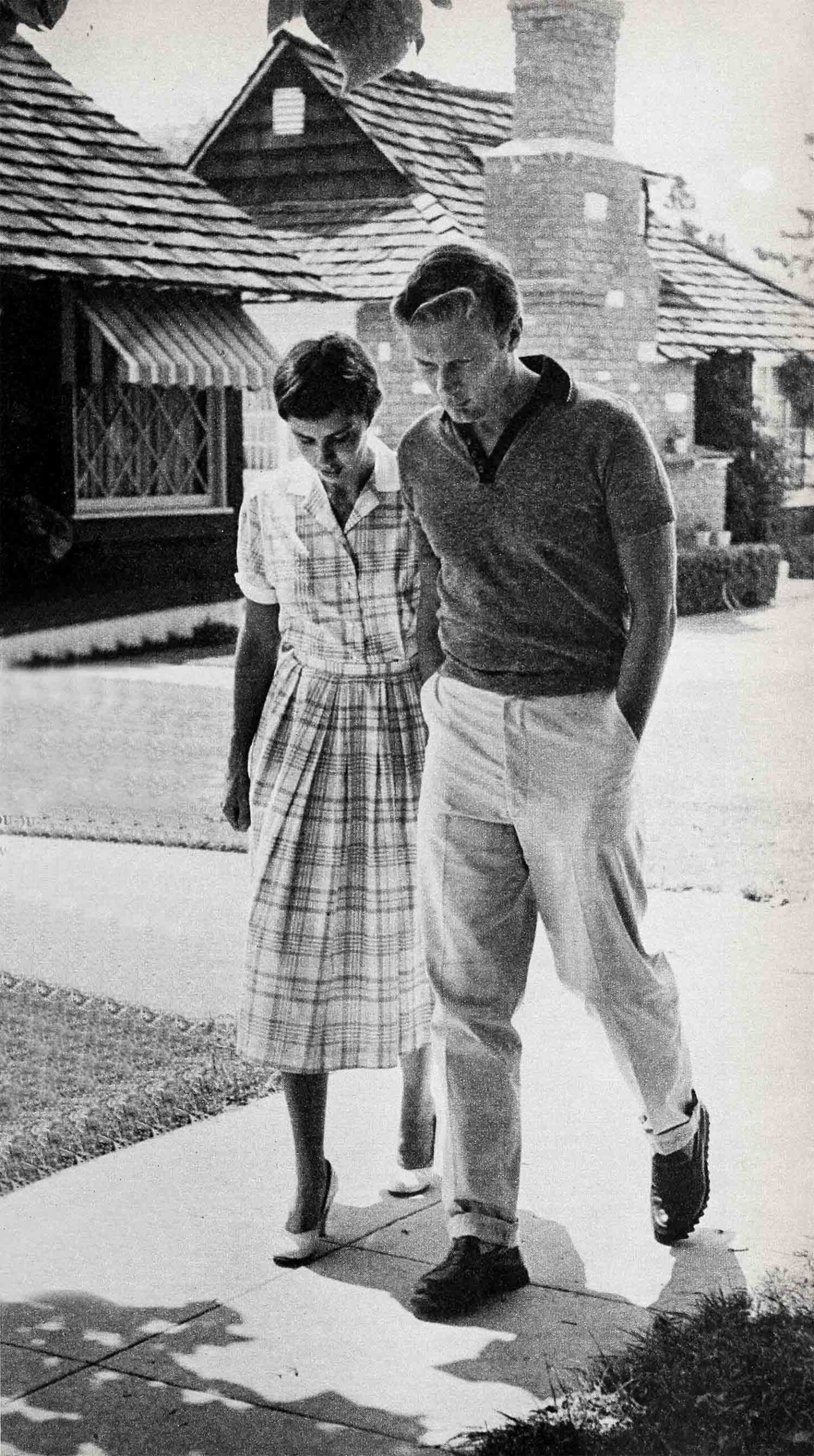

Deeply hurt and puzzled, Dick Gardner wonders, “How can my wife ask me to leave Hollywood, to quit a job that’s so much a part of me?”

“But our marriage wouldn’t last six months if I stayed here!” Joan Gardner says, close to tears. “What marriage does have a chance in Hollywood? Just name me one!” She collects herself and begins her side of the story, with her husband’s silent consent.

“I didn’t marry an actor,” she tells you, pulling worriedly at a curl of her dark, short-cropped hair. “I married a boy who was going into his father’s construction business and would have a business of his own some day. We had a lovely home and a wonderful family life back in Waterloo, Iowa. Now, suddenly, he’s an actor.”

As she speaks, Joan’s troubled hazel eyes are on the handsome blond guy she’s loved since they were both sixteen. In their rented cottage on a quiet street in North Hollywood, the beamed ceiling and the brick fireplace give their living room a cozy, home-like atmosphere to your eyes, the visitor’s eyes. But it isn’t home to Joan. She’s perched on the edge of her chair as she says, “We were so happy in Waterloo—if I could only get Dick to go back with me now . . .

She breaks off, and then recovers. “Dick has adjusted to Hollywood, but I can’t. This just isn’t the kind of living I’m used to.” For the past three years, Joan has been commuting periodically between Hollywood and Waterloo, Iowa; but for the past three months she and the children have been here with Dick, trying to solve the problem his way. Now the time of decision has come, and Joan is fighting in her own way to save their marriage and home. “If I go back there and stay,” she says desperately, “he will come, too—if he loves me.

“We were school sweethearts, and we eloped when we were eighteen. We were so sure we wanted to spend the rest of our lives together that we couldn’t wait to begin. We’re still in love now—we want our marriage to last. And we have two wonderful reasons for making the effort. They’re playing outside . . . Ruthie! Mike!”

Eight-year-old Ruth Ann obediently comes in, a lovely little lady with her father’s hair and her mother’s eyes. Politely, she introduces you to her doll, Beth, who’s also from Waterloo, and shows off the tiny wardrobe “My grandmother made it for her. It’s her mink stole,” Ruth says, carefully smoothing a sliver of rose taffeta. “Sometimes I take her and play with a girl over there and one over there,” she says, motioning vaguely across the street. “Mommie, can I go there now?” And Ruth Ann’s on her way.

Trailing along late is a bright-eyed, bushy-haired five-year-old, who enters with: “I’m Mike and I have a hula hoop.” He wriggles around inside the red plastic circle, volunteering the added information that “Greg teaches me—he lives next door. See, Daddy? You do it like this.”

Dick gives his son a quick hug and an affectionate spank. But his face saddens as he watches Mike run out into the sunshine again. “I wonder . . . How much do they notice?”

“Sometimes I think Ruth Ann senses,” her mother worries. “Sometimes she doesn’t act natural—and I wonder what she’s thinking. I tell them Dick’s job is in California, and because he’s so busy we can’t live here all the time just now. Ruth doesn’t push me for any other reason, she accepts that one. But when they get a little older . . .

“I thought maybe if I brought the children out here and spent these months with Dick, we would come to some kind of understanding,” says Joan. “It’s just no good the way it has been.”

But now, the months are over. And they’ve settled nothing. Joan’s bags are half packed. And the closest Dick is to Waterloo, Iowa, is the maple tree in a front yard two streets away. “There’s a maple just like it back home,” Joan says wistfully. “I wish you could have seen our place there,” she adds, looking around her at these green walls bare of pictures or family treasures of any kind. She glances uneasily at the dining table with its piles of publicity pictures and fan mail and the typewriter on which Dick spends so many hours writing to a public Joan doesn’t know. No, this isn’t home for her.

Home for both of them used to be the house they bought and furnished back in Waterloo, a lovely, rambling house with shutters, with a split-rail fence around it and big oak trees to shade it.

“In Waterloo,” Joan says, “my husband finally did have his own real-estate and contracting business, and he averaged maybe $1,000 a month. I had my own car, and I sent all my washing and ironing out. Our friends were the people we grew up with in school and in Sunday school, at the Methodist church.

Joan comes from a family of school-teachers and would have taught if she hadn’t married so young. Security in the steady paycheck, security in her own home and in marriage—these to her are all-important. And these she had. She offered no objection when Dick began working with the community playhouse. As she says, “I felt everybody has to have a hobby—and this, I thought, was Dick’s. Hollywood was just a place you read about in a magazine.”

Loving Dick, she is thrilled and proud whenever she sees him in a motion picture or on a television screen, but there’s always the dark thought that his success can mean their defeat. “If Dick is going to be a star some day—and I definitely think he will be if he stays out here—he’s going to be gone an awful lot,” Joan says. “They’re doing so many pictures overseas now! If I’d been in Hollywood when he was making ‘The Young Lions,’ I’d have been all alone with the children for eight weeks. And,” she continues, “there’s no family life in Hollywood at all. We’d never be together. When Dick is working in Hollywood, he leaves early in the morning and gets home so late he wouldn’t see Ruth and Mike even if they were here. And when he isn’t working he’s so restless and depressed—there’s no family life then, either. Sunday, we went down to the beach. Dick was depressed, and it irritated him to have the kids running around and kicking sand on us. We can’t even seem to enjoy a family outing any more.

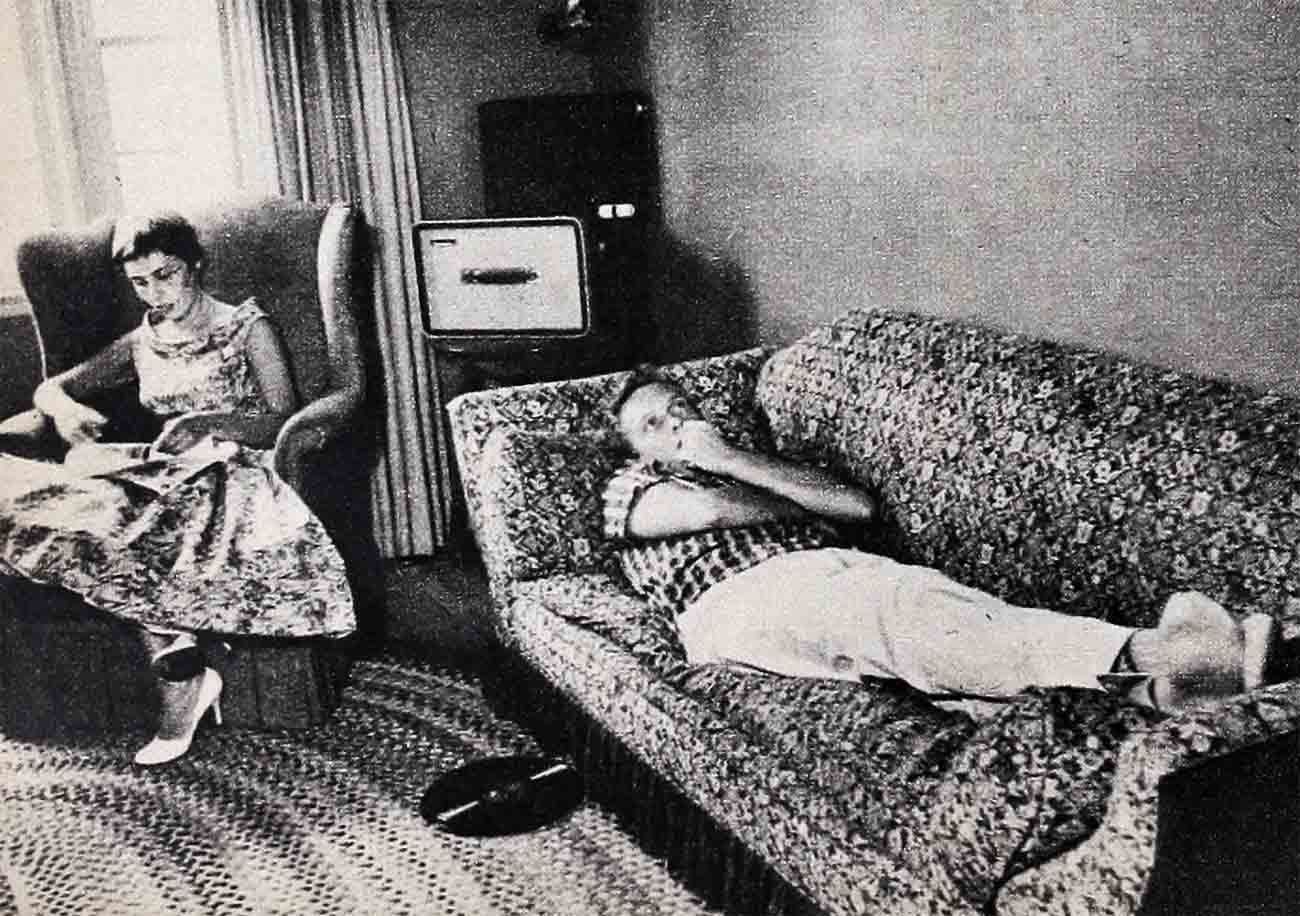

“Nowadays Dick’s either on Cloud Nine or ’way down in the cellar. And when he’s in the cellar—well, I’ve seen him a little moody back home, but never like this. So remote and restless. When he gets depressed he takes off and goes to a movie—and you’re just left home hanging there. Or he listens to records like the scores from ‘East of Eden’ and ‘Rebel Without a Cause’—the most morbid music I’ve ever heard in my life—and nobody can get through to him. It makes me sick inside to see him like this. Then I get upset and on edge with the children and try to keep them from bothering him and . . . well, all doesn’t make for good family life.”

Unaware of all she herself has to offer, Joan is also afraid that “Dick will find somebody else. I don’t see how any man could keep from becoming involved,” she says, “when he’s thrown day after day with the same people—the most beautiful girls in the world.”

Almost angry, Dick is about to speak up. But he lets Joan finish: “I’m going to stay here a little while longer. I’ve never been here while Dick was working, and he’s to start a picture right away. Maybe when he’s working it won’t be as bad as I believe it will be . . .”

And then she adds wearily, “But perhaps we’re just putting off something that’s going to happen anyway. We used to have so much in common, but now . . . I know time will be against us if Dick gets any more involved in his career. Time is running out for us even now . . .”

“Don’t say that, darling.” Dick’s voice is unsteady, and he looks at his wife with deep concern. “There’s still time. But this nonsense about beautiful girls—!” He turns to you and says earnestly, “For me, Joan is the only beautiful girl, the only girl I’ve ever loved. And I’ve loved her for so long. It’s just that . . .”

“Go ahead, darling,” Joan says softly. “I’ve spoken my piece. Now it’s only fair if—” She, too, turns to you. “If Dick tells you how things look to him, if people can see the whole picture—well, maybe somebody can help us.”

We wait as Dick organizes his thoughts and finally he puts them into words, choosing each carefully. “When I began working with the community playhouse, I think Joan just hoped it was a hobby. She must have known that it was serious, that some day I would be going into the acting profession full-time. For me, the real-estate and construction business was only a means to an end. I was building a stake for us, so we wouldn’t have to go through what others do trying to get a start in Hollywood.

“If I went back to Waterloo now, I’d really be unsettled,” Dick says firmly. “This business is in my blood. The acting profession has something you can’t put into words. You can’t explain it, but it’s there. And you can’t get it out. If I thought I had to build houses the rest of my life— then I’d really be unhappy!

“Maybe I’m old-fashioned,” Dick goes on, “but I think a man is the head of the house, he supports his home and family and I feel I should have the right to pick my profession. I spend two-thirds of my time in whatever work I’m doing; and if I’m not doing something I’m happy in—then I’m just taking two-thirds of my life and throwing it away.

“It would be different if nothing had happened to me here. But in the time I’ve been in Hollywood, I’ve done quite a bit in television and movies. I made $10,000 in the business last year. Why should I give it up now and go back home? Why shouldn’t Joan live here with me? I feel a woman should be with her husband—whatever he’s doing—even if he’s digging ditches in Africa.”

The yearning to act grew inside Dick when he was in his early teens. He remembers giving sermonettes in the basement of the Methodist Church for the young people on Sunday evenings. “I liked doing this because I seemed to be able to control the kids—their emotions—with the way I would phrase the words or my tone of voice. I meant to be a minister then—but I found with acting it was the same thing. I was in school plays and I got as far as the state speaking contests.”

In many of these early audiences was a girl with long pigtails and big hazel eyes. “The first time I really noticed Joan,” remembers Dick fondly, “was when my cousin was visiting me and we were looking for somebody for him to go with. I was going past Joan’s house when she came out on the front porch with a shirt and shorts on, and I thought, ‘Well, she’d be a good girl for him to go with.’ Then I took a second look and decided she’d be a good girl for me to go with,” he grins.

Sixteen years old, in love for the first time, Joan and Dick would go for romantic summer canoe rides on the Cedar River. In the winter, she would wait for him after basketball games or stand outside the football stadium in the freezing cold, waiting with the usual bunch of girls.

They decided to elope the summer they were eighteen, in spite of the opposition of Joan’s parents, who felt that they should go to college and that they were just too young. But, Dick says, “Two young kids, you know, can’t be told anything.”

And so, one August morning, Dick and Joan eloped to Kansas City, 300 miles away. But in Kansas City the judge wouldn’t marry them because Joan was under age. Dick recalls, “I told him that it was such a distance to our home it would take us all night to drive back. For us to have been out all night together—and not married—seemed to me to be infinitely worse than his marrying us even if Joan were under age. But he couldn’t see it that way.”

They went to an attorney to see what he could suggest. “I told him my story—how I felt about us being out all night and not being married—and he sent us to a judge he knew in Olathe, Kansas, and he married us,” Dick grins. “After the ceremony, we went out and had an ice-cream soda—and then we went to a movie, ‘The Postman Always Rings Twice.’ About halfway through it, we were so dead-tired we began falling asleep in the theater. Suddenly we said, ‘What are we doing here? We could have gone to a movie in Waterloo!

And so they went home, to start the happiest part of their life together. By the time Dick Gardner was twenty-one, he was the youngest real-estate and building contractor in the state of Iowa. But his future was in another field, he soon discovered. “I worked for five years with the community playhouse, and it was really great experience. We put on plays in Waterloo during the winter and during the summer we’d tour them all around Iowa, Wisconsin and Illinois. I told Joan then I was getting background for a career in New York or Hollywood, but she just didn’t take me seriously.”

Six years ago the Gardners came to California on a vacation. Walking along Vine Street, Dick was stopped by a fellow who asked whether he was interested in television. “He gave me his card,” Dick recalls, “and we went to some studio and I read for them. They said they’d be very interested in using me if I was going to stay out here permanently. I was so excited about it that I wanted to go to Waterloo and settle things and come back here to stay. But then we found Joan was pregnant, and she didn’t want to make the change.”

Three years later, however, the Gardners came to California again, “more or less on a vacation—but really to check into the situation, too,” says Dick. This time, he met a star who set the stage and decided his future for him.

Dick and Joan were driving around San Fernando Valley one sunny Saturday afternoon, studying the architecture of various homes. As a building contractor, Dick was making mental notes on western ideas. “We were,” he says, “especially interested in the structure of Clark Gable’s home in Encino, and I drove up to get a better look at his house. There was Gable, standing in the yard. I got out of the car and went over to him. I couldn’t do anything else—I’d driven right up in his face!

“We talked for two hours. I told him what Id been doing back home in the theater and what I wanted to do. He told me how tough it was to get started out here. But then Gable asked me—he asked me!—whether I’d like him to help me. I told him, naturally, ‘That would be wonderful,’ and he said, ‘Well, I don’t know what I can do, but I’ll at least line you up with my agents. I’ll make an appointment for you for next Monday.’”

Joan bursts in: “Do you know where I was all that time? Just sitting in the car, scared stiff, wondering how we’d ever had the nerve to drive in.”

Smiling at her, Dick continues, “Next week my new agent took me to all the studios, where I read for studio heads. However, they weren’t hiring any contract players at the time. But then Paul Gregory, who’s from Iowa, put me in two of his productions, ‘Caine Mutiny Court Martial’ and ‘The Day Lincoln Was Shot,’ ninety-minute television spectaculars and two good credits for me. I did a ‘Frontier’ series and a couple of ‘Matinee Theaters.’

“Meantime, Joan had gone back to Iowa. But she flew out twice and told me to forget the whole thing. One day I wrote Dick Powell a letter, and he invited me to his office, where we talked for an hour and a half. He said he was going to Europe, but when he came back he’d be producing at 20th Century-Fox. He asked me to look him up when he got back from Europe.

“That did it! I decided to go home and sell everything and come out here permanently. My dad fought the idea. But I knew this was the moment! I had the contacts, the experience and a $16,000 nest egg.

“I told Joan then, ‘It isn’t a question of our having to skimp like some do. We’ll just have to face the fact that we can’t have a second car like we do at home.’

“But Joan wouldn’t come with me. Instead, she moved in with her folks. She said she’d bring the children and join me after I got things settled. So I rented this three-bedroom place, furnished in Early American. Then Joan changed her mind. She said she was staying in Waterloo, and she wanted me to go back and join her there.”

The struggle of words began: letters, long phone calls. Joan flew to Hollywood and pleaded with Dick to go back with her to Waterloo. He flew home for Christmas—and flew back.

For the first time came the dreaded word—divorce.

Fighting for his personal happiness, Dick still forged ahead professionally. He contacted Dick Powell at 20th and, he says, “Dick set me up with the talent program at the studio. I lost out on a part in ‘Fraulein’ but got one in ‘Desk Set,’ another in ‘Kiss Them for Me.’ Then came my best part, as Private Cowley in “The Young Lions.’ We locationed in Europe, but I can’t say I even enjoyed Paris. I’d go out to buy clothes for Joan—and I didn’t know from one minute to the next whether she was going to file divorce papers.”

The situation was deadlocked, and it has stayed that way. In his Hollywood home, Dick asks wearily, “Isn’t Joan just borrowing trouble at this point? She reminds me that we’d have had a lean year salary-wise if it hadn’t been for ‘The Young Lions.’ That’s true, but the fact remains I did make the $10,000. And I’m sure that I can do it again.

“Joan says I get depressed and moody. Well, maybe she’s partly right,” Dick agrees. “I don’t fool myself. But when I feel this way I do something about it. I go to a movie and study others’ performances. That ‘morbid’ music? I always listen to music when I’m going to do a part; it creates a mood for me.”

And then Dick comes back reluctantly to the most delicate question of all. “As for Joan’s fears that I’ll suddenly up and divorce her to marry some Hollywood glamour girl—well, in my opinion these girls aren’t even beautiful. A beautiful girl, in my opinion, is one who can be good-looking without eyebrow pencil or pancake. A natural beauty is what I like—like Joan. She has a shine to her hair, a sparkle to her eyes, her skin texture is good. Besides, actresses have too many artifices; they’re always trying to be somebody else. I fell in love with Joan because she’s a down-to-earth girl.

“I think she’s being realistic,” Dick admits, “when she says it’s tough to make marriage work in Hollywood, with all the frustrations, the insecurity of not knowing what’s going to happen next. Yet, if love is strong enough—and I believe ours is—these problems can be overcome.”

A cloud shadows his hopeful mood. “But there’s got to be a lot of give as well as take . . . I’m willing to give. I’d love to be able to commute—live in Waterloo and work in Hollywood. If I were in a position where the studios were coming to me, I could fly out for a picture. It’s only six hours by air. I like a small town’s intimacy and the chance to have close friends of long standing. And if living in Waterloo would make Joan happy, it would make me happy.

“But now isn’t the time to think about that. Now, there are twenty-five other actors waiting for the same parts that I want—waiting like me for a phone call. I just can’t leave Hollywood now.”

Dick bows his head in despair. But then he looks up and the hopefulness stubbornly returns. “Believe me, I’d welcome any advice that could help Joan and me. Ours isn’t just a Hollywood problem, I’m sure. Somewhere there must be other couples who’ve been uprooted and separated because of a man’s work. How do they find the answer? If people will listen to our story—Joan’s side of it and mine, too—maybe one of them can give us the word that will keep us together, where we belong. I hope—” Dick glances at his wife, sees her sad smile and gentle nod. He goes on, “—And Joan hopes, too, that they will write and help us.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1958

No Comments